Since the 21 October 2024 agreement on disengagement and patrolling between India and China, the debate surrounding the future contours of India-China relations has gained significant prominence in India. The release of the Economic Survey in July 2024 had sparked similar interest in the outlook for India-China ties. The two countries which share a long and complex relationship faced heightened tensions post the 2020 Galwan border clashes that marked first fatalities in 45 years in largely peaceful borders. This violent episode, coupled with the pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic and escalating geopolitical volatility led to a reassessment of one of the most fundamental assumptions girding the bilateral relationship. For years, the Indian government sought to keep the issue of the border separate from broader India-China relations, but the Galwan crisis changed this approach. Many high-level diplomatic meetings were frozen. However, trade continued unabated despite the abnormal state of bilateral relations.

In recent years, China's dependencies have shifted from technology-intensive advanced economies to commodity-exporting nations, primarily in the Global South. Unlike China, which has a highly coordinated industrial policy driven by national goals, India has traditionally placed emphasis on low-cost imports rather than developing domestic capabilities. However, India must now move beyond a cost-driven approach and focus on developing a product-driven economy that can build long-term global competitiveness. In a statement from the Modi-Xi meeting on the margins of the 16th BRICS Summit in October 2024, the Chinese side asserted that China and India are each other's “development opportunity” rather than a threat. [1] The Indian side underlined the “need to progress bilateral relations from a strategic and long-term perspective, enhance strategic communication and explore cooperation to address developmental challenges. [2]” The desire for cooperation is clear, but challenges remain.

Trade Imbalance: A Persistent Challenge

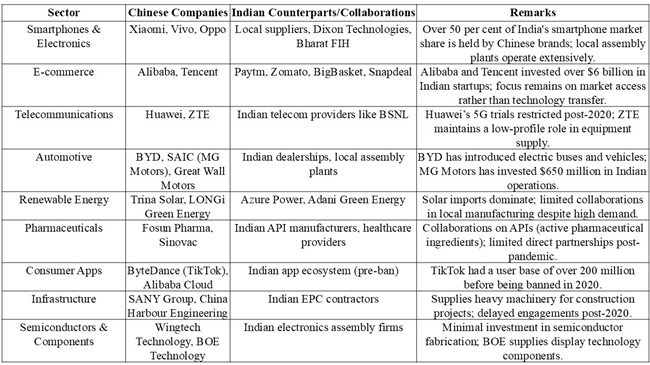

The trade imbalance between India and China has remained a significant issue for years. In FY 2023, India's trade deficit with China reached a staggering $85 billion. Despite efforts to reduce this imbalance, India’s dependence on Chinese imports across key sectors—including automobiles, pharmaceuticals, electronics, and renewable energy—has remained substantial. A major driver of this dependency is the incomplete supply chains, especially at the Tier 2 and Tier 3 levels in critical sectors. Press Note 3 of 2020, released by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, sought to regulate foreign investments from countries sharing a land border with India, particularly targeting Chinese investments. Following the Galwan crisis, the Indian government implemented restrictions on public procurement and banned a significant number of Chinese apps. The Enforcement Directorate also increased scrutiny of Chinese companies operating in India.

However, the Economic Survey 2023-24 presented a more pragmatic approach, suggesting a revaluation of India's stance on Chinese investments. It categorically noted that despite rhetoric of “de-risking” and “China plus one strategy,” Chinese supply chains remain quintessential in face of diversion of US trade from China. India's global value chain (GVC) participation had grown steadily until the global financial crisis, with foreign value-added content in exports rising from 10 per cent in 1995 to 22 per cent in 2009. Thus, India will inevitably, require linking with China's supply chain, via investment or imports, for boosting Indian manufacturing and integrating in GVCs. [3]

Economic and Technological Security: Whither Engagement?

In recent years, economic and technological security has emerged as a top priority for many nations. China's growing economic dominance, control over critical resources and technologies, and use of economic statecraft to advance geopolitical goals have compelled countries to reassess their dependencies. India, grappling with a significant trade deficit—over $100 billion in imports compared to just $16 billion in exports—faces substantial challenges. Despite measures like Press Note 3, which screens investments from bordering nations, India still lacks a comprehensive understanding of its reliance on China, particularly in key sectors and critical infrastructure. As China has increasingly weaponized economic engagement for scoring political points, there is even more urgency for understanding the breadth and depth of bilateral and international economic engagement pertaining to China. One illustrative case is China’s obstruction of tunnel boring machine imports, which are essential for building border infrastructure. During the 7th India-Germany Inter-Governmental Consultations in October 2024, Union Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal raised this issue with German Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck, highlighting how China’s actions were hindering India’s procurement of said machines from the German firm Herrenknecht. [4]

India has been ramping up efforts to reduce vulnerabilities in critical areas particularly by boosting local production and cutting import dependence on key pharmaceutical ingredients from China. Two newly inaugurated greenfield plants mark significant progress in this direction. Lyfius Pharma, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Aurobindo Pharma, is set to produce 15,000 metric tonnes of Penicillin G at its facility in Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh. Meanwhile, Mumbai-based Kinvan Private Limited (KPL) has begun operations at its 400-MT plant in Solan, Himachal Pradesh, manufacturing Clavulanic Acid, a crucial active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) for bacteria-resistant antibiotics. [5]

However, some argue that India cannot entirely decouple from Chinese technology, given China's dominance in high-tech sectors. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute's Critical Technology Tracker 2024 reveals that China leads in 57 of 64 advanced technologies and accounts for 31 per cent of global manufacturing. India, in comparison, contributes only about 2 per cent and achieving technological parity with China could take nearly two decades. In the interim, strategic engagement with China could mitigate the opportunity costs of isolation. For instance, India could leverage China’s expertise in energy transition technologies to drive mutual benefits.

India’s approach to foreign direct investment (FDI) from China should balance caution with strategic engagement. Currently, FDI from China accounts for less than 1 per cent of total FDI in India. Since 2014-15, when Prime Minister Modi visited China, Chinese investments have been primarily concentrated in sectors like telecommunications, where they have captured significant market share. Despite efforts to attract more diverse investments, these inflows have not significantly contributed to enhancing India's manufacturing capacity. The Press Note 3 regulation offers a pre-screening mechanism for Chinese investments rather than imposing a blanket ban. Over the last four years, a significant number of Chinese investment applications have been approved. However, continuous post-investment monitoring is essential to improve the quality and impact of FDI. India also needs to evaluate the tangible benefits of Chinese investments in terms of capital inflow, technology transfer, job creation, and access to global markets. In many cases, these benefits have been limited. Much of the investment has been concentrated in startups, with minimal technology transfer and job creation. Additionally, exports from Chinese companies operating in India to global markets remain constrained. But Shein returning to India after a ban of almost four and a half years, through a partnership with Reliance Retail could be a step in that direction. [6]

Meanwhile, the political instability and faltering economic growth in many states across the Indian subcontinent have underscored India’s role as a bastion of democracy and economic progress. The growing global acknowledgment of China’s industrial overcapacity has also prompted Chinese policymakers to rethink their external investment and trade strategies. Whether this shift will influence Beijing’s engagement with India, however, remains uncertain.

Building Strategic Capacity for Critical Sectors

India’s focus must shift toward identifying specific sectors where it can become a global leader and supporting those sectors through targeted policy interventions. India's success in sectors like space and defense demonstrates its potential to compete globally when it has a clear strategy and engages the private sector effectively. By focusing on select industries and providing a predictable policy environment for the next 15 years, India can foster national champions capable of competing globally.

One area that needs urgent attention is semiconductor manufacturing. Establishing semiconductor fabrication plants with policy support and incentives will be key to reducing India’s dependency on Chinese imports. The sector is already seeing investments with Foxconn’s OSAT investment and Tata’s Gujarat fab, with plans for expansion. Government efforts under the India Semiconductor Mission have focused on new hubs like Greater Noida, supported by global partnerships with Tokyo Electron, Tower Semiconductor, and the US. Private players like L&T and startups under the Design Linked Incentive (DLI) Scheme are also enhancing chip design and local production to reduce import dependency. [7] Similarly, boosting domestic production of communication and telecom hardware is vital to reduce imports from China. The National Policy for Electronics (NPE) 2019 envisions India as a hub for Electronics System Design and Manufacturing (ESDM), aligned with the Make in India initiative.[8] In 2023, India’s electronics production reached $102 billion, with component demand at $45.5 billion. [9]

India’s ambitious target of achieving 500 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 faces challenges due to its reliance on imported solar equipment, particularly from China. Over 60 per cent of India’s solar imports come from China, and in FY 2024, these imports were valued at $7 billion. Projections from the Global Trade Research Initiative indicate that this could surge to $30 billion annually by 2030 if domestic production does not scale up. [10] China, which dominates over 80 per cent of the global solar panel market, has tightened export regulations on advanced technologies like large silicon, black silicon, and cast-mono silicon to safeguard its leadership. Despite efforts under PLI scheme, India’s solar manufacturing remains largely dependent on imported components, with 90 per cent of production focused on assembling cells rather than full-scale manufacturing. To reduce this dependency, India must prioritize investments in upstream production, such as polysilicon and wafer manufacturing, while fostering international partnerships to build a robust and self-reliant solar industry.

Conclusion: A Pragmatic Approach for the Future

China is not India’s civilizational enemy; it is a geopolitical rival. While complete decoupling from China is unrealistic, India must prioritize reducing its vulnerabilities in critical sectors while continuing to engage with China where necessary. The aim should be for more favourable terms of engagement with China, without being overly ambitious about outcomes. Strategic collaboration with other global powers, such as the US, EU, and Japan, will be crucial in reducing reliance on Chinese supply chains, especially in high-tech sectors like semiconductors, telecommunications, and renewable energy. Recent advancements in India-US technology cooperation, including defense exports where 50 per cent of Indian exports go to the US, underscore the importance of aligning interests in countering China's influence. However, India must also ensure that deepening ties with the US does not restrict its strategic autonomy. India must adopt a long-term strategy that balances the risks and opportunities of engaging with China, while focusing on building domestic capabilities, diversifying sources of imports, and improving global competitiveness.

References

[1] President Xi Jinping Meets with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202410/t20241023_11514914.html

[2] Meeting of PM with Mr. Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China on the margins of the 16th BRICS Summit, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/meeting-of-pm-with-mr-xi-jinping-president-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-on-the-margins-of-the-16th-brics-summit/

[3] External Sector: Stability Amid Plenty, www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/eschapter/echap04.pdf

[4] 'I think I should listen to you': German Vice Chancellor to Piyush Goyal on China blocking tunnel boring machine sale, https://www.hindustantimes.com/business/i-think-i-should-listen-to-you-german-vice-chancellor-to-piyush-goyal-on-china-blocking-tunnel-boring-machine-sale-101730091971473.html

[5] India's import dependence on key pharma ingredients may reduce by half, https://www.business-standard.com/industry/news/india-s-import-dependence-on-key-pharma-ingredients-may-reduce-by-half-124111000342_1.html

[6] Shein to re-enter Indian market after 4 years with Reliance's Ajio launch, https://www.business-standard.com/companies/news/reliance-retail-shein-india-return-ajio-fast-fashion-124122400282_1.html

[7] India’s Semiconductor Sector: Tracking Government Support and Investment Trends, https://www.india-briefing.com/news/setting-up-a-semiconductor-fabrication-plant-in-india-what-foreign-investors-should-know-22009.html

[8] India's Electronics Manufacturing and Export Market, https://www.ibef.org/research/case-study/india-s-electronics-manufacturing-and-export-market

[9] India’s Electronics Manufacturing: Tackling Challenges, Seizing Opportunities, https://www.india-briefing.com/news/indias-electronics-manufacturing-challenges-and-opportunities-35363.html/

[10] India’s Solar Panel Import Bill Could Hit $30 Billion, https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/Indias-Solar-Panel-Import-Bill-Could-Hit-30-Billion.html

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://indbiz.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/iStock-1093161914.jpg

Post new comment