On January 26, 2025, India is honoured to welcome the 8th President of Indonesia, Prabowo Subianto, as the chief guest of the Republic Day celebrations. This important diplomatic occasion not only symbolizes the warm, contemporary ties between the world's largest democracies but also invites reflection on the more than a millennia-long relationship that India and Indonesia have enjoyed. From the early centuries of the Common Era—when Hindu-Buddhist influence steadily made its way into the Indonesian archipelago—to the later emergence of powerful kingdoms such as Majapahit till the 16th Century, the story of India-Indonesia relations is one defined by deep cultural affinity, linguistic exchange, and spiritual cross-pollination for simply sixteen hundred years. [1]

Today, as both nations stand at a juncture of defining their roles in an ever-evolving global order, the memory of a shared cultural past continues to galvanize their relationship. Instances of “Indianization,” or the influx of Indian culture, religious ideas, and scripts into the Indonesian islands, remain etched in inscriptions, temple architecture, manuscripts, and historical records. Scholars from both countries—and indeed from around the world—have recognized the role of Sanskrit, the Pallava script, and Indian makavya (epics) such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata in shaping traditional Indonesian art forms, languages, and statecraft.

Amid this backdrop, one remarkable artefact stands out: the Airlangga’s principal Inscription, often referred to as the Pucangan Inscription or Calcutta Stone, dated 1041 CE, which is housed at the Indian Museum in Kolkata. This Inscription offers direct insight into the reign of King Airlangga, one of the most revered kings of Java, a patron of art and literature, Kakawin Arjunawiwaha, adapted from the Mahabharata. He stood as a seminal figure in early 11th century Java, whose lineage and deeds testify to the deep cultural confluence

between India and Indonesia. [2]

The proposition of returning this Inscription to Indonesia as a symbolic gesture of solidarity resonates powerfully with the spirit of mutual respect, shared heritage, and diplomatic goodwill—underscoring that cultural treasures are often best appreciated within their original sociocultural environment.

India and Indonesia: Over 1,600 Years of Shared Heritage

The earliest evidence of this exchange can be seen in inscriptions found in Indonesian locales such as Kutai (in eastern Kalimantan), which bear Sanskrit words engraved in Pallava script derived from the southern part of India. Over time, various Javanese and Sumatran polities, including Sriwijaya (Srivijaya) and the kingdom of Mataram, emerged as major centres of higher education, mostly about Buddhist and Hindu scriptures, establishing an intellectual and spiritual nexus stretching across the Bay of Bengal. Sanskrit became the language of statecraft and religious texts, while the Old Javanese language.

By the late first millennium, powerful kingdoms like Mataram in Central Java showcased Indian temple architecture and religious motifs, exemplified by the majestic Borobudur (Buddhist) and Prambanan (Hindu) temple complexes—world-renowned testaments to this vibrant cross-cultural influence. The subsequent centuries saw significant political, religious, and cultural developments in the archipelago, culminating in East Java's emergence as a dominant political centre. The shift of power from Central Java to East Java led to the rise of new dynasties and set the stage for figures like King Airlangga, who deftly navigated the intersection of indigenous traditions and imported Indian ideas.

Thus, the India-Indonesia historical relationship rests on a legacy of shared spiritual traditions and written cultures. Scholars from both countries have devoted substantial efforts to deciphering inscriptions, manuscripts, and stone reliefs—texts demonstrating the evolution of the region's hybrid culture. This shared heritage has remained a cornerstone of the modern rapport between India and Indonesia, permeating many layers of diplomacy, popular culture, and national identity.

King Airlangga: A Ruler Bridging Two Worlds

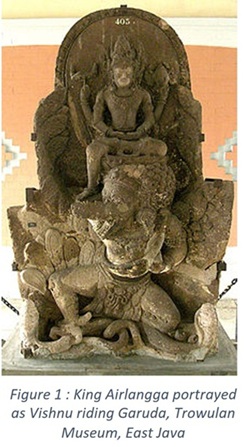

King Airlangga (r. 1019–1049 CE) stands out as a unifying figure among the various monarchs who illustrate the depth and complexity of India-Indonesia historical ties. He was the scion of a royal lineage that connected both the Balinese and Javanese courts and is sometimes believed to be the son of the Balinese King Udayana and the Javanese princess Mahendradatta. Airlangga’s ancestry symbolizes the synergy between the different islands of the Indonesian archipelago, mirroring the broader interplay of cultural currents from India.

Airlangga’s era was a tumultuous time. The Mataram kingdom (often also referred to as Medang) in Central Java had fallen into disarray in the early 11th Century, partly due to internal conflicts and external invasions. In 1019, Airlangga ascended to power amidst this upheaval, eventually consolidating a realm often referred to as the Kahuripan kingdom. His principal seat of power was in East Java, though his sphere of influence extended into various neighbouring regions. [3]

Airlangga’s Contributions and the Significance of His Inscription

Like many Javanese rulers, Airlangga upheld the ideal of the “chakravartin”—the universal monarch—emulating Indian conceptions of a righteous king.

One of the most direct windows into King Airlangga’s life and legacy is an inscription commonly referred to by two names: the Pucangan Inscription (named after its original discovery site near Mount Penanggungan or Pucangan in East Java) and the Calcutta Stone (on account of its long-term residence in the Indian Museum in Kolkata). This Inscription exemplifies the intricate trajectory of influences that shaped Airlangga’s rule. The Inscription is significant for being composed in both Sanskrit and Old Javanese, illuminating the coexistence of an Indic lingua franca for ceremonial and scholarly discourse alongside the local language. Sanskrit was often employed for official court inscriptions, especially when articulating genealogies and justifying kingship in the context of broader “holy war” (dharma-buddha) or cosmic rulership. Meanwhile, Old Javanese was the vernacular medium for local record-keeping and literary compositions. Those two languages appear side by side in the same Inscription, which underscores the cultural duality of Airlangga’s kingdom and the depth of India’s linguistic and literary influence.

The Inscription details Airlangga’s lineage, including references to his father and mother, thereby legitimating his right to rule by establishing a royal pedigree steeped in tradition. It also recounts episodes of warfare, coronations, and religious foundations, giving scholars precious insight into the political turbulence and subsequent stabilization efforts in early 11th-century Java. By marking the events that shaped Airlangga’s early struggles and eventual triumph, the Inscription reveals how he restored order and prosperity after a period of disruption. Airlangga is praised for upholding dharma and the cosmic order.

On November 9, 2024, Minister of Culture of Indonesia Fadli Zon requested the return of the Pucangan Inscription from his Indian counterpart, Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, during the G20 Culture Ministers' Meeting in Brazil. Discovered in the early 1800s by Stamford Raffles and later gifted to Lord Minto, the British governor-general, the artefact has been housed at the Indian Museum in Kolkata ever since. Fadli Zon emphasized that returning the Inscription would revitalize Indonesia's cultural identity, proposing the handover coincide with President Prabowo Subianto’s 2025 visit to India.

Cultural Identity and National Narratives:

Ancient kingdoms, epics, and historical characters in India and Indonesia form crucial elements of nationalist narratives. For Indonesia, figures such as Airlangga, Ken Arok, and Gajah Mada are revered as exemplars of leadership and unity. Likewise, India's mythological and historical legacies inspire pride and national cohesion. Recognizing that parts of this heritage overlap foster a sense of camaraderie: Indians can take pride in contributing to Indonesia's cultural evolution, while Indonesians can celebrate their creative adoption and transformation of Indian influences.

By returning this artefact, India would demonstrate a tangible acknowledgement of Indonesia's heritage. This reverential respect speaks volumes about India's commitment to honouring the shared past rather than asserting ownership, especially regarding artefacts with significant cultural meaning to the other nation.

Continuity of Knowledge Tradition

Even after repatriation, forging academic and museum partnerships is possible. High-quality rubbings, 3D scans, and digital reconstructions of the original stone can remain in the Indian Museum, ensuring that researchers in India continue to have access to the artefact’s textual content. Meanwhile, the physical stone’s presence in Indonesia would deepen local historical consciousness and provide a new focal point for educational and cultural tourism.

The Enduring Legacy of a Shared Heritage

As we consider the importance of returning the Airlangga Inscription, it is vital to remember that this artefact is a single piece in a vast mosaic of shared heritage. In many ways, India's ancient knowledge traditions—encompassing Sanskrit, the epics, religious philosophies, and script forms—were seeds that took root in fertile Indonesian soil, blossoming into distinct local cultural expressions. The centuries-old shadow play of Wayang Kulit, which depicts stories from the Indian mahakavya, attests to the creative synergy of these cultures. Similarly, adapting Indian temple architecture in structures like Candi Sukuh or Candi Panataran in Java testifies to the Indonesian reinterpretation of Indic motifs.

This synthesis was never unidirectional. Indonesia—especially in the era of powerful maritime kingdoms like Sriwijaya—emerged as a formidable Buddhist learning centre that attracted scholars from across the region, including Indian monks seeking texts or heading further east. The shared maritime heritage, anchored by the Indian Ocean's busy trade routes, enabled the spread of goods and the exchange of ideas and artistic practices. Indeed, the story of King Airlangga is inseparable from this maritime cultural connectivity: Java’s prosperity in his time relied heavily on trade facilitated by routes that touched the Indian subcontinent.

Modern India and Indonesia, with large youth populations and burgeoning economies, stand poised to carry this legacy forward innovatively. Interfaith dialogues, cultural festivals, educational collaborations, and digital archiving of ancient texts highlight the longstanding conversation between the Ganga and the Java Sea. The physical handover of a cherished artefact from Indian to Indonesian soil could be a clarion call for rejuvenating these ties, reminding us of the capacity of culture and history to bridge contemporary divides.

The upcoming visit of the President of Indonesia, Prabowo Subianto to India as the chief guest for the 2025 Republic Day offers a pivotal opportunity to celebrate the enduring ties between these two nations.

References

[1] Juergensmeyer, M., Roof, W. C. (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. India: SAGE Publications. P.557

[2] Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824803681.

[3] Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824803681. pp.145-147

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://asset.kompas.com/crops/kRvREJERfhKwrBQS4XmNsPbFiqY=/0x10:924x626/1200x800/data/photo/2022/08/05/62ed1ed23c6d1.png

Post new comment