The 1990s were a time of global change. The fall of the Berlin Wall led to Francis Fukuyama arguing in The End of History and the Last Man that western liberal democracy had triumphed and there was to be nothing thereafter in the developmental narrative. There was unparalleled assertion and muscle flexing on this account, believing that all previous narratives were conquered, and that new narratives were to be brought about. In this backdrop, the world saw the emergence of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Forest Principles at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

We, in India, were not very far away from change, either. The balance of payments crisis, the continued change of government, a reorientation of economic policies, and most importantly, our place in the world — all shaped our policies. Post-Rio, the then Ministry of Environment and Forests, saw the divisions of climate change and biodiversity brought to life.

Climate change has come to be the epitome of all challenges requiring global collective action, but where are we actually headed? A recent study[1] argues that from 1970–2017, developed countries with only 16% of the world population were responsible for 74% of excess resource use over their fair share. Over the same period, 58 countries, including India, representing 3.6 billion people, stayed within their sustainability limits.

Global GHG Emissions and India

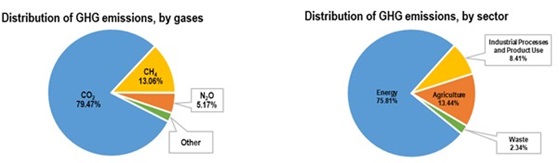

As per the 6th Assessment Report of the Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6 WGIII), global net anthropogenic GHG emissions were 59 ± 6.6 GtCO2eq in 2019. Global climate change is largely due to excessive emissions (both historical cumulative as well as current) of the developed countries. India, on the other hand, is consistently separating carbon emissions from its economic growth. The figure below depicts India’s emissions, gas-wise and sector-wise. In 2019, India’s gross GHG emissions were 3.1 billion tonnes of CO2eq, and its net emissions were just 2.6 billion tonnes of CO2eq. Various agencies have ranked[2] India for its annual and cumulative emissions. India ranks 129th based on cumulative per capita CO2 emissions from 1960-2018, 7th based on cumulative historical CO2 emissions from 1850-2020, 6th based on cumulative emissions (excluding Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry) from 1850-2019, 5th based on cumulative emissions (excluding LULUCF) from 1990-2018, and 4th only if based on current annual emissions.

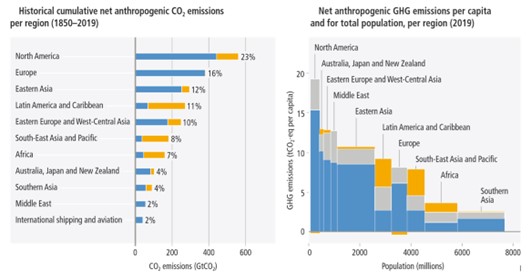

The figure below depicts how greenhouse gas emissions were distributed unequally throughout different parts of the world from 1850 to 2019 (IPCC, 2022). It illustrates that all of Southern Asia (including India) contributed only about 4% of historical cumulative CO2 emissions between 1850 and 2019, despite being home to almost 24% of the global population. The per capita net greenhouse gas emissions ranged from 2.6 to 19 tCO2eq, with the global average being 7.8 tCO2eq. The crucial point is that India’s annual and cumulative emissions in absolute and per capita terms have been significantly low and far less than its equitable share. India, relative to its responsibility and what equity demands, is doing far more than its fair share.

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_SummaryForPolicymakers.pdf

Amidst this stark contrast, how does India view its climate policy?

Determinants of India’s Climate Policy

India’s climate policy is based on five major determinants: Geography, Population, Impacts, Worldview and Actions.

India’s Geography makes it the 7th largest country, having an area of 3.28 million km2 but just 2.4% of the world’s area and 4% of the world’s freshwater resources. It is one of the 17 mega-biodiverse countries with 4 biodiversity hotspots, 10 different bio-geographic zones, and 22 agro-biodiversity hotspots. India experiences six different seasons – Vasant (Spring), Grishma (Summer), Varsha (Monsoon), Sharad (Autumn), Hemant (Pre-Winter), and Shishir (Winter) captured by poets like Kalidasa. India’s civilization and economy developed in harmony with this seasonal cycle. However, in recent decades, climate change has disrupted this harmony by blurring the distinction between seasons, leading to unpredictability and negative consequences for nature and society.

India views its population of 1.4 billion as an asset and a source of strength. India hosts 7-8% of the world's documented species, encompassing over 45,500 plant species, 91,000 animal species, and myriad undiscovered microbes. Its low human-to-land ratio, at 0.0021 square kilometers, necessitates a nuanced approach to sustainability, integrating land and water management while adapting to this constraint for sustainable survival. India’s forests are teeming with wildlife. They support ~70% of the global tiger population, >60% of Asian elephants, ~80% of the one-horned rhinoceros, 100% of the Asiatic lion population, and thousands of endemic species, making India one of the 17 mega bio-diverse countries in the world. Twenty percent of our total CO2 emissions were removed from the atmosphere by our forest and tree cover in 20193.

The impacts of climate change have persistently presented challenges. According to the Global Climate Risk Index 2020, India ranks as the fifth most affected nation, grappling with an increasing frequency of extreme weather events. Further, a 2018 World Bank report forecasts that the country could incur a loss of 2.8% of its GDP due to rising temperatures and shifting monsoon rainfall patterns. According to Kotz et al. (2024) [5], the global economy is expected to lose about 19% of its income in the next 25 years due to climate change, with countries in Africa and South Asia being the least responsible for the problem and having the minimum resources to adapt to impacts suffering the most.

Our Worldview is shaped by our ancestors; of living in harmony and consonance with Nature. The four Vedas of India, among the oldest texts in the history of humankind, are replete with respect and adoration for Mother Earth. The Prithvi Sukta of the Atharva Veda says that, “माता भूमिः पुत्रोऽहं पृथिव्याः” which means the ‘Earth is our Mother’, and we are her children. Sacred groves signify our deep and intrinsic connection with Nature. Western science often depicts forests and trees as large receptacles or dustbins for soaking and storing CO2! In India, forests and trees are revered and worshipped. India’s forests provide all four types of ecosystem services: provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural. India firmly believes in empathy for all fellow species on earth and reverence for Nature as the only way to sustainability, choosing moderation over profligacy.

Gandhi’s ideals of trusteeship and the ability of Earth to provide enough for everyone’s needs, and not greed, place our thrust on moderation over profligacy. The logo of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change — Nature Protects if She is Protected — reflects reverence for Nature and our continued conservation stance.

Our Actions are shaped by science, based on evidence. India’s historical contribution to cumulative global GHG emissions is minuscule, despite being home to ~1/6th of the world’s population. India’s per capita annual emissions are about a third of the global average. Notwithstanding, India has taken resolute domestic and international actions benefiting the planet. From building the International Solar Alliance to a sharp focus on transitioning to renewable energy and reducing the emission intensity of GDP by 33% (2005-2019)3, our actions are for the benefit of the planet. This is unlike developed countries, which show enthusiasm for climate action for everyone but themselves! Take, for instance, the United States of America, which has entered and exited the international governance mechanism for climate change at free will – right from the signing of the UNFCCC in 1992. Can we take developed countries' pledges and commitments seriously in the light of such inconsistency?

The Evolution of Climate Policy

India’s climate policy is informed by inclusive growth for all-round economic and social development, the eradication of poverty, a declining carbon budget, firm adherence to the foundational principles of the UNFCCC, and climate-friendly lifestyles. India stands by these principles and values in supporting multilateral action on climate change. India’s climate policy has always been Clear, Consistent and Coordinated.

It is clear that the problem of climate change has been the result of overexploitation of natural resources by developed countries. It is consistent as India has been a strong voice of the global South, largely responsible for bringing the CBDR-RC principle. Domestically, India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change, 2008 having eight missions has laid the groundwork for understanding and acting on climate change. It is coordinated as climate policy is a multisectoral effort with over 23-line Ministries at the Centre and States, along with civil society, that take part in the decision-making process. India’s efforts to address Climate Change are immediate, ambitious, planned, and cover every sector of its economy.

India is a world leader in climate action today, adding two more C’s to its Climate Policy- that of Confidence and Convenient Action embracing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s slogan – Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas and Sabka Prayas. India has reflected this Confidence by first renaming the Ministry of Environment and Forests to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change to centralize the domestic and international actions around climate change and then building global institutions such as the International Solar Alliance, Coalition of Disaster Resilient Infrastructure and the Global Biofuels Alliance. With the Lifestyle for Environment movement, India shows that Convenient Actions are the only way possible, and that India’s sustainable lifestyles are the way forward.

However, notwithstanding these efforts, accelerating India’s efforts at climate action is not a journey that India can undertake on its own. Given their over-appropriation from the global carbon budget, the developed countries owe India a carbon debt, and indeed to the entire global South. The developed countries need to honour their commitments under the convention to provide the means of implementation to developing countries, including both climate finance and technology transfer that is adequate in terms of scale, scope and speed. In developing countries, India included, adaptation to climate change is an overwhelming concern and an overriding priority.

Development and environment are two sides of the same coin and must be taken together for all-round holistic development. Unless the world truly embraces the age-old Indian ethos of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam – One Earth, One Family, One Future, we will be unable to solve a global collective action problem like climate change. Unlike the Cold War and the unipolarity thereafter, the world craves newer, sustainable, achievable, and realistic ideas to tide over the effects of climate change and not any ‘ism’ based on western imports or rhetoric. India’s model of sustainable development must act as a rallying cry for developing countries to counter the narratives presented by the developed world, bringing science and evidence to the forefront of policy-making.

References

[1] Jason Hickel, Daniel W O’Neill, Andrew L Fanning, Huzaifa Zoomkawala, National responsibility for ecological breakdown: a fair-shares assessment of resource use, 1970–2017, The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 6, Issue 4, 2022, Pages e342-e349, ISSN 2542-5196, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00044-4. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542519622000444)

[2] Bhatt, J. R., Debunking the narrative of India as a large greenhouse gas emitter. Current Science. June 2023. https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/124/12/1378.pdf

[3] MoEFCC. India: Third National Communication and Initial Adaptation Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. New Delhi: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, 2023. https://moef.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/India-TNC-IAC-revised.pdf

[4] IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023, pp. 1-34. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001

[5] Kotz, M., Levermann, A. and Wenz, L. “The economic commitment of climate change.” Nature, 2024, 628, 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0

(Views are personal. An abridged version of this article was published by The Indian Express.)

image courtesy: Author

Post new comment