China has the fastest growing navy amongst the major powers of the world with a current strength of about 340 ships including 125 major combatants and submarines[1]. This growth has come about in the last couple of decades at a rapid pace as China aims to become a global maritime power by the middle of the century. This growth has also been accompanied by a doctrinal shift wherein the country desires that the “traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned”[2]. In pursuance of these ambitions, the People’s Liberation Army (Navy) (PLAN) has gradually been enhancing its capabilities through conduct of exercises with various countries, primary among them being Russia.

China and Russia share a friendship that has “no limits” where there are no “forbidden areas of cooperation”[3]. The military domain has especially witnessed heightened engagement between the two countries over the past two decades. While engagement between the ground forces of the two countries was at the forefront of this partnership in the early years, naval exercises between the two have become increasingly visible since 2012. The importance attached to this interaction is evident in that, notwithstanding the current conflict in Ukraine, naval exercises between the two have seen an upsurge with five such events having been conducted over the past year. In fact, the two navies recently concluded a month-long joint patrol in the Pacific Ocean in August 2023 wherein they were sighted as far as the Aleutian Islands, in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the USA[4]. These joint exercises reflect an increasing convergence between the two countries even as the USA and the West look at them as a coalition, if not a de facto alliance. An analysis of these exercises can be a good indicator of the state of the China-Russia relationship and its likely trajectory in the near future.

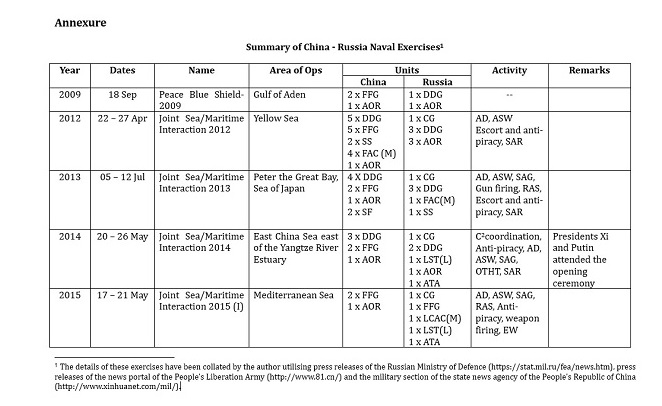

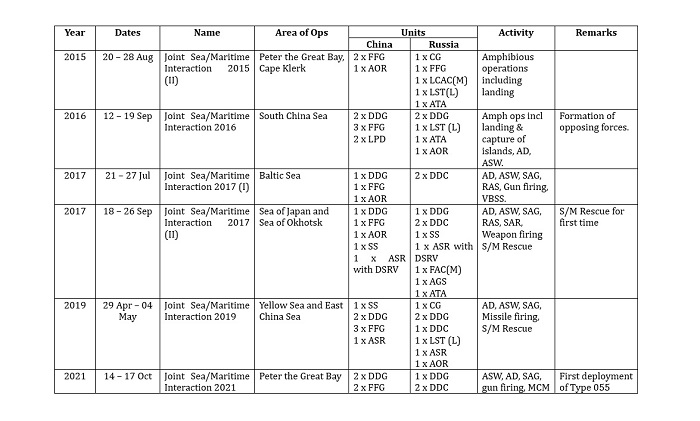

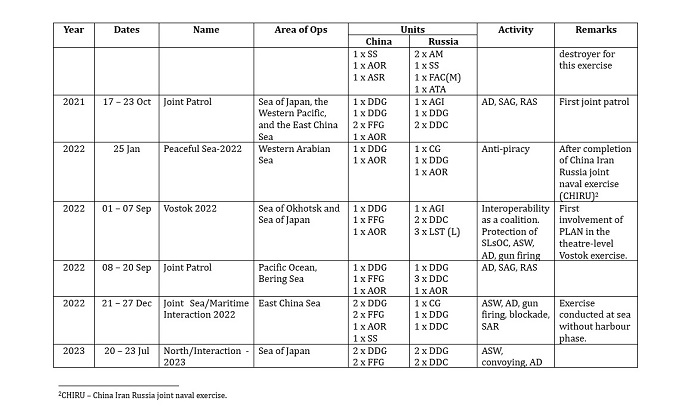

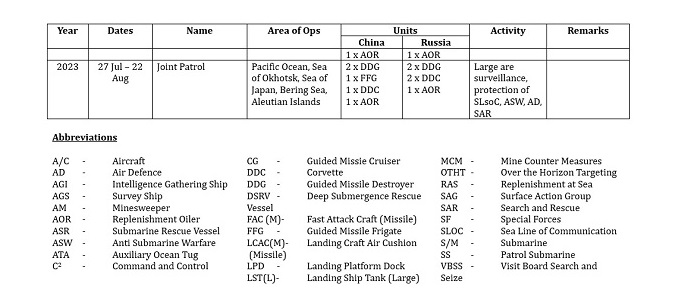

Joint naval exercises between the two navies began in the wake of the PLAN’s first anti-piracy deployment to the Gulf of Aden with the first ‘Peace Blue Shield-2009’ taking place in the same region on 18 Sep 09. While this exercise seems to have been a relatively simple affair, subsequent iterations have witnessed an increase in the number of ships from either side as also complexity of tasks undertaken. These exercises have been an annual affair with interruptions in 2018 and 2020. While the pandemic precluded conduct of this exercise in 2020, the reason for not conducting it in 2018 is not known though there were some unverified reports of Chinese naval participation in the Russian theatre-level ‘Vostok 2018’. A list of the joint naval exercises is placed at an Annexure at the end of this essay to provide a birds-eye view of the level of involvement and the type of missions/tasks undertaken during the conduct of these evolutions.

Areas of Exercise: A large number of these exercises have been conducted on the eastern seaboard of China and Russia with some being conducted in the Arabian Sea and two even in the Mediterranean and the Baltic. The focus on the eastern seaboard is especially consequential for China since it views this region as the primary strategic direction of threat[5]. The East China Sea and South China Sea, where China has territorial disputes, as also the question of Taiwan, necessitate this choice of area since this would not only allow gaining of naval expertise in this vital region but also convey the extent of the ‘no-limits’ partnership to adversaries like the US, Taiwan and other littorals and claimants in the maritime disputes. Deployments especially the joint patrols to the Pacific are another indicator of the joint reach of both the countries, especially for the US. The couple of exercises conducted in the Mediterranean and the Baltic with the Russian Black Sea and Northern Fleets respectively, appear aimed at indicating Chinese support for Russia in this part of the world while also hinting at Chinese maritime capability to protect its overseas assets, especially along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR), in the Mediterranean and Europe.

Ships and Aircraft: Some of these exercises, like the one in 2012, have witnessed the participation of more than 20 ships. Notwithstanding, most of these exercises have involved, on an average, about 5 – 7 ships from each side though some iterations have witnessed a lesser number. Nearly all the large ships, like the cruisers, destroyers and frigates have carried their own integral helicopters for these exercises. The inclusion of the new Type 055 class destroyer Nanchang, a year after its commissioning, in the 2021 edition of the bilateral exercise, indicates the confidence that the PLAN has in the integration of ships into its fleets. In addition, shore-based aircraft for maritime reconnaissance, anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and airborne early warning (AEW), from both forces, have been regularly employed in consonance with the ships at sea. Interestingly, the Chinese have yet, not deployed their aircraft carrier for these joint exercises, possibly because of lack of integration of this platform into their own navy and due to an absence of sufficient procedures for a joint exercise with a foreign navy. The employment of a variety of platforms, from cruisers to tugs and replenishment ships, indicate a high degree of comfort of operations of the two navies with each other. While much of this would have been possible due to development and streamlining of common operating procedures, the likelihood of commonality of equipment and systems between the two navies (due to the Soviet influence as also acquisition of Russian platforms) would have also helped.

Submarines: Both countries have frequently deployed submarines, albeit only conventional, in these exercises regularly. They also conducted a submarine rescue evolution in 2017 employing their respective deep submergence rescue vessels (DSRV). Such deployments would have augmented their interoperability in the art of submarine rescue and allow future utilisation of these assets in any emergency in either navy. The possibility of providing this facility to other submarine-operating navies in the Indo-Pacific is also a distinct possibility since both, the PLAN and the Russian Navy, have earlier participated in multi-national submarine rescue exercises. Operations of submarines also indicate a high level of confidence in each other’s capabilities even as both navies stand to gain operational expertise in the underwater domain in areas of interest like the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan.

Missions/Tasks Conducted: These exercises have evolved from conduct of basic tasks for development of common procedures to simulations of combat between two opposing forces. The focus of much of this effort seems to have been on surface action with areas like air defence (AD), anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and weapon firing. However, firing of missiles and torpedoes has not been carried out frequently, indicating a possible lack of comfort in this area or a lack of resources for these drills which are fairly intensive in terms of employment of assets. Nevertheless, simulated firings of these weapons would have been undertaken during the conduct of these exercises. Much of this activity would also have been accompanied by concomitant electronic warfare overlay, considering the continuously developing expertise of the Russians in this field of warfare[6]. The Chinese would also have imbibed knowledge of network centric operations, which the Russians have focussed on in the recent past, especially when viewed in the context of the multiplicity of platforms deployed during some of these exercises. Missions like over-the-horizon-targeting (OTHT) involves passing of information in real time form airborne platforms or distant pickets to ships to engage targets at long ranges with missiles and necessitates network centricity for efficacy of interdiction. Another evolution that has seen frequent occurrence has been the escort of high value shipping and the practice of anti-piracy procedures. These, along with convoying become critical during a conflict for protection of one’s own sea lines of communication (SLsOC) and vital commerce. Considering the susceptibility of China’s SLsOC to interdiction by its adversaries, Russian help, if possible, will be a welcome aid during hostilities. The wide spectrum of evolutions conducted is a clear indicator of the high level of interoperability between these two navies which will surely push the limits of the ‘no-limits partnership’.

Amphibious Operations: The two navies have undertaken a number of amphibious operations as part of the bilateral exercises with the first one being conducted in 2015 at the landing sites of the Russian Pacific Fleet’s training ground near Cape Klerk (Peter the Great Bay). This exercise was possibly intended as a preliminary training for the subsequent undertaking of a similar exercise, albeit with an expanded mission of landing as also capture of islands, in southern China’s Guangdong province in 2016. In fact, this exercise simulated opposing forces which would have helped China in understanding the dynamics of amphibious operations in its area of interest (Guangdong abuts the South China Sea and is close to Taiwan). China has been focussed on building its amphibious capability with continued accrual of large amphibious ships like the Type 075 Landing Platform Dock (LPD) amongst others. In fact, the ‘Joint Sea/Maritime Interaction 2016’ featured two of the Type 071 LPDs, currently in service with the PLAN. These exercises have also featured a large number and variety of shore-based aircraft including fighters, strike, airborne early warning (AEW) and shop-borne helicopters to simulate the actual complexity of such operations. Existent Russian proficiency as also the legacy of Soviet capabilities in this field of naval warfare seems to have been the incentive for the Chinese navy to focus on this aspect of naval operations in its engagement with the Russian Navy. However, the absence of this element from subsequent iterations of the bilateral exercises appears to indicate the completion of the mission requirements for the Chinese though this may need to be watched in the future.

Theatre-Level Exercise: Chinese naval participation in the Russian theatre-level exercise ‘Vostok – 2022’ indicates a very high level of comfort and interoperability for not just the two navies, but between the higher command organisations of the two militaries. While the Chinese ground and air forces have taken part in earlier Vostok exercises, this was the first time that the PLAN was taking part. This exercise was intended to enhance the capabilities of the two navies and militaries in repelling a joint threat while also protecting maritime commerce and their vital SLsOC in the Pacific. Consequently, the ability of the respective command organisations to operate and synergise their respective naval capabilities both, in joint and individual capacities, was exercised which indicates a very high level of joint as also integrated operations of the two militaries.

Joint Patrols: The increasing proximity and convergence of military objectives between the two militaries, is reflected in the joint patrols undertaken by the two navies in the Pacific. The footprint of these patrols has extended from the East China Sea to the Sea of Japan and thence into the Pacific, as far as the Aleutian Islands in the Bering Sea. Very often, these patrols have traversed the EEZ of the USA in the area of the Aleutian Islands. While the first patrol was a relatively short one, of about a week, the recent one in July/August 2023 lasted nearly a month. On an average, 8 – 10 ships have been deployed for these patrols by the two navies possibly intended to signal a joint show of strength to adversaries like the USA. While the objective of these patrols is ostensibly to show the flag, the meaning is not lost on the US and its allies. Operationally, these deployments, especially with an intelligence gathering vessel being part of these formations, would have helped in gaining valuable information about adversarial militaries of the USA, Japan and South Korea.

Experience of the Adversary: The USA and its allies have had extensive military deployments in the Western Pacific over the past five years or so, in response to Chinese maritime aggression in the East and South China Seas, while also being concerned about the rapid growth of the PLAN. Conversely, these deployments have led to close-quarter situations with the Chinese navy, which in a back-handed way have actually helped the PLAN gain operational knowledge of the US forces, especially about their sensors and modus operandi. The conduct of many of the China-Russia naval exercises in the Pacific, where US forces are present both by design and default, would have helped these two navies accrue a store of operational knowledge about their adversary. In fact, it can even be surmised that some evolutions may have been designed to experience actual adversarial presence in evolutions like EW and ASW[7].

Joint Exercises with Other Navies: The PLAN and the Russian Navy have also jointly exercised with the Iranian navy in the Gulf of Aden and adjoining areas since 2019. While these exercises have been focussed on anti-piracy, the grouping has generated perceptions of geopolitical alignment considering the bilateral proximity between the three nations. The Russian and Chinese navies have also undertaken joint exercises with the South African navy on two occasions, in 2019 and recently in February 2023[8]. These exercises involved anti-piracy drills and protection of SLsOC. These multilateral exercises appear to not just reflect the aspirations of Russia and China to have a global footprint but to generate an alternative to the West-led order for protection and safeguarding of the seas and global commons.

These joint exercises will have provided substantive operational gains for both navies, even as the Chinese navy aspires to be a global power while the Russian navy aims to regain its lost stature. The exercises have helped in generation of joint capabilities and interoperability which, when required, can be utilised in the future for combating a joint threat. The growing complexity of these joint exercises is also a reflection of the growing “friendship with no-limits”. As the partnership has strengthened, so has the proximity between the two militaries, and the navies, growing from strength to strength. Importantly, these naval exercises along with other military drills have enhanced the level of trust in the two militaries. Considering the number of joint projects underway between the two militaries in the recent past, the development of joint capabilities in domains like underwater warfare and air defence, leveraging their respective technological strengths in areas like artificial intelligence, will be a reality in the near future.

These exercises have also served in ‘power projection’ of the PLAN to ‘overseas’ areas like the Mediterranean while also consolidating its presence in disputed regions in the East and South China Seas. China’s ambitions to become a global a maritime power and provide an alternative to the current world order are clearly reflected in these exercises, especially with the involvement of Iran and South Africa in these evolutions. Russia’s hand has also been strengthened with the perception of a military alliance gaining currency amongst its adversaries as these exercises have ventured into warfighting realms and possible regions of future conflict. While there does seem to be a level of convergence and even complementarity in the objectives of the two countries and their navies, it remains to be seen whether the perceptions of a military alliance between the two will turn into a reality, especially in the current geopolitical context of a weakened Russia and a China which is struggling with serious internal economic problems while facing an increasingly adversarial international community.

Endnotes

[1] ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022: A Report to Congress’ at https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23321290/2022-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-peoples-republic-of-china.pdf. (Accessed 30 Nov 22).

[2] ‘China’s Military Strategy (2015)’ at

http://english.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm. (Accessed 20 Aug 15)

[3] ‘Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development’ at http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770. (Accessed 07 Feb 22).

[4]Dzirhan Mahadzir, ‘Russian-Chinese Warship Group Pulls into Qingdao’, USNI, 22 Aug 23. https://news.usni.org/2023/08/22/russian-chinese-warship-group-pulls-into-qingdao. (Accessed 24 Aug 23).

[5]Xiao Tianliang, ‘The Science of Military Strategy’, National Defense University Press, Beijing, 2020, pp. 3.

[6]Roger McDermott, ‘Russian Navy Procures New Electronic Warfare Capabilities’, Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 14, 05 Feb 19. https://jamestown.org/program/russian-navy-procures-new-electronic-warfare-capabilities/. (Accessed on 10 Mar 20).

[7] ‘China, Russia and Iran hold joint naval drills in Gulf of Oman’ at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/15/china-russia-iran-hold-joint-naval-drills-in-gulf-of-oman. (Accessed 20 Mar 23).

[8] ‘China Announces Joint Naval Drills with Russia, South Africa to Safeguard Sea Transport, Maritime Economic Activities’ at https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202302/1285684.shtml. (Accessed 22 Feb 23).

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/976/cpsprodpb/6FD6/production/_128403682_russianfleet.png.webp

Post new comment