China’s emergence on the global stage has been accompanied by a clear pronouncement of its ambitions to be a global player with Xi Jinping emphasising the “global significance of the Chinese dream”[1]. China also perceives an inadequacy in representation of the developing countries, the global south, including itself, at the international stage and seeks to address this deficit through a reform of the global governance system. President Xi Jinping has been quite vocal about the need for reform of global governance and has often underlined the necessity for consultation in “exercising contemporary international governance”[2]. Leading the reform of the global governance system has now become one of the ten tenets of Xi’s thoughts on Chinese foreign policy[3]. This thought has been fleshed into distinct initiatives over the past few years culminating in a ‘Proposal of the People's Republic of China on the Reform and Development of Global Governance’ issued by its foreign ministry on 13 September 23[4].

Proposal for Reform of Global Governance

This proposal has been mooted in the backdrop of the supposed 10th anniversary of President Xi’s concept of “building a community with a shared future for mankind” , an idea that he has often mentioned at various international fora in the past. Interestingly, this concept has been subsequently fleshed out by China in a White Paper on 26 September 23, barely two weeks after outlining this proposal. China perceives deficits in the domains of international security, global development governance, food security, green development & climate change, human rights, social governance and promotion of civilisational exchanges. China puts forward its proposal for the reform of global governance in this light as a solution to “common challenges” while underlining it continued support to the “international system with the United Nations at its core”. China’s proposal highlights its earlier proposed initiatives, i.e., the Global Security Initiative (GSI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI), as aimed at meeting global governance deficits in these domains.

The GSI was officially mooted by President Xi Jinping at the Boao Forum in April 2022 and has since been formalised as a concept paper published by the foreign ministry of the PRC on 21 Feb 23. The GSI espouses the concept of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security, again something that Xi Jinping has been talking about and which has also been broached by Chinese leaders at various international platforms like the Munich Security Conference[5]. Another aspect of this approach is what China terms as “legitimate security concerns”, possibly alluding to its position on the Ukraine conflict wherein it has stated that the security of one country should not be pursued at the expense of others[6]. China’s involvement in global “hotspots” like the Korean peninsula and more recently, in Afghanistan, appears to have provided it some credence for becoming a player in the resolution of these issues. Its apparent mediation in the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran also seems to have furthered its objectives in this domain. Deriding the US for the withdrawal from Afghanistan and the subsequent absence of any commitment for the reconstruction of that country seems to be another tenet of this proposal. China also espouses nuclear security and a reduction of the threat from nuclear weapons, even as it increases its own arsenal and enhances the means of delivery of these weapons. The GSI also addresses new and emerging domains like information security, artificial intelligence (AI) and outer space. While China does not overtly propose the GSI as a panacea for these issues, it cites the GSI as a platform for addressing security concerns on account of many of these issues. The GSI aims to promote the establishment of a balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture, largely based on existing Chinese-driven mechanisms like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia, the “China+Central Asia” mechanism and the like[7].

The Global Development Initiative (GDI) was also proposed by President Xi, albeit earlier than the GSI, at the 76th session of the UNGA on 22 Sep 21, in the context of revitalising the global economy in the wake of the pandemic[8]. The initiative has also been dovetailed with the UN SDG 2030 agenda with the concept paper ‘Building on 2030 SDGs for Stronger, Greener and Healthier Global Development Initiative (GDI)’ being circulated at the UN in September 2021[9]. Xi talked about the need to accord higher priority to development needs in the global macro policy agenda while emphasising on more equity in global development in order to “accelerate the implementation of the UN SDG 2030 Agenda. The focus of this effort is on the developing countries, primarily the global South, and extends to alleviating debt burdens and enhancement of development aid. Another direction of effort is the diffusion of technology to enhance digital connectivity and accelerate development in these countries. The GSI’s claimed priority areas for cooperation include poverty alleviation, food security, COVID-19 and vaccines, financing for development, climate change and green development, industrialisation, digital economy, and connectivity. China has pushed this initiative quite vigorously at the UN by creating a Group of Friends (GoF) of the GDI, which counts about 70 countries as its members[10]. The initial list of about 50 projects under this initiative were undertaken largely in countries of the global south in South East Asia, Central America, sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific Islands and this number has since doubled. Much of the funding for these projects has come from China though the UN has also contributed through some of its programmes like the UNDP and the WFP. Most of these projects have been undertaken in the socio-economic domain for issues like poverty alleviation, pandemic response and food security. Importantly, the GDI has garnered the support at the highest levels of the UN with the Secretary General underlining the GDI as “valued contribution to addressing common challenges and accelerating the transition to a more sustainable and inclusive future”. Despite President Xi’s efforts of broaching the GDI with his counterparts during bilateral interactions, the GDI has not found much support amongst the developed world, most likely because of China’s continuing geopolitical frictions with the US and Europe.

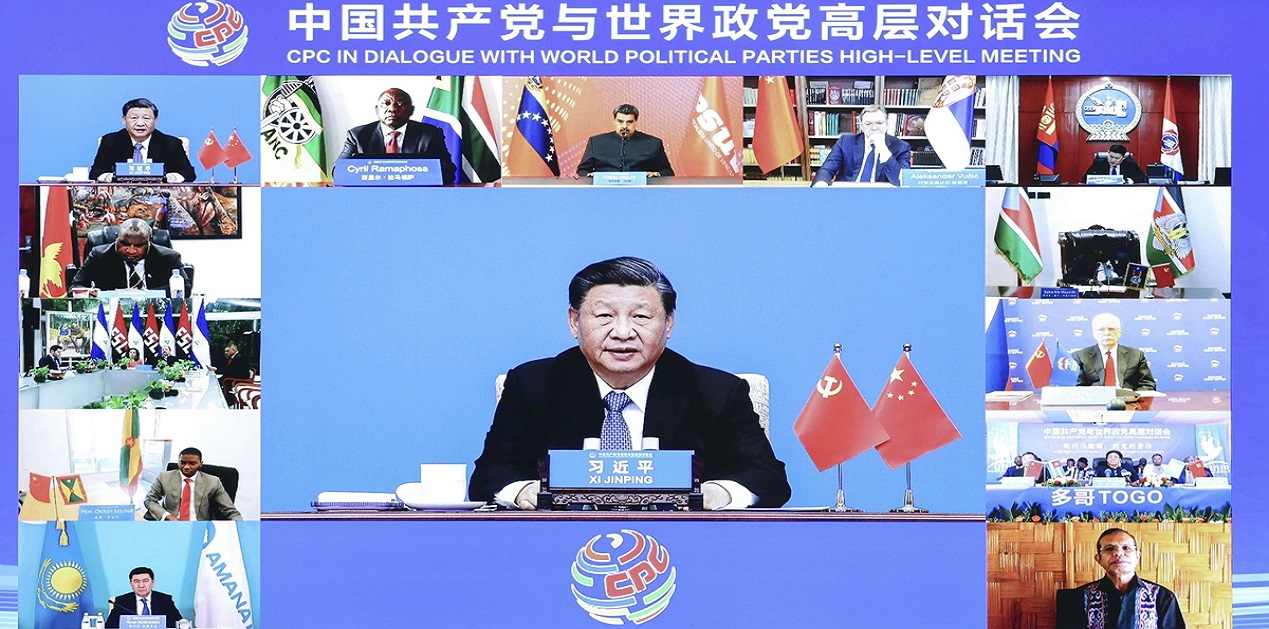

The most recent of President Xi’s proposals, the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI), was mooted by him, not at an inter-governmental forum but at a ‘Dialogue with World Political Parties’ organised by the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) on 15 Mar 23 in Beijing[11]. This initiative, in part, also stems from Chinese aspirations to be a “socialist cultural power”, an objective laid out in the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025)[12]. The GCI is intended to stimulate international civilisational exchanges, an idea that Xi talked about in a speech at the ‘Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations’ in 16 May 19[13]. While this forum was intended for political parties, many leaders who are Heads of State/Governments like the Presidents of South Africa, Nicaragua, Serbia, South Sudan and the Prime Ministers of Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and Mongolia attended the forum amongst others. Xi put forward five propositions in the proposals, which essentially revolve around the theme of pursuing modernisation in accordance with separate needs of a country and not according to a universal template. Underlining the leadership of the CPC and its role in China’s “rejuvenation” as also a flag bearer of its modernisation is quite clearly intended to highlight the capability of single-party states to push forward national development. Building a global network for inter-civilisation dialogue is one of the intended deliverables of this effort. The GCI is yet to be clearly etched out by the Chinese and it is quite likely that a concept paper, on the lines of those for the GDI and the GSI, will be published in the near future.

All these initiatives and the proposal for reform of global governance are anchored in Xi’s concept of a ‘community with a shared future for mankind’, an idea that he has often talked about from the time he took over the reins of the CPC and the country. While Xi has broached this concept at many an international forum and in bilateral meetings, it was not clearly outlined till recently.

Global Community of Shared Future

China published a white paper on “A Global Community of Shared Future: China’s Proposals and Actions” on 26 Sep 2023[14]. This paper fleshes out the details of Xi’s concept of a ‘Community with a Shared Future for Mankind’, which he had first proposed (formally) at the 71st session of the UNGA[15]. This concept is credited with being the fount for the launch of all Chinese global initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as also the GDI, GSI and the GCI. While the white paper claims that this concept is not intended to “replace one system or civilisation with another”, it talks about countries with different social systems, ideologies, histories, cultures and levels of development coming together, which actually reflects on the Chinese perception of an ideological and civilisational conflict being perpetrated by the West. The overhang of this perception is very evident in the espousal of openness and inclusivity citing the apparent domination of the current international order by a few countries and the consequential inequity and imbalance thereof. The ‘global community of shared future’ is unequivocally stated as China’s strategy for reforming and improving the international governance system.

The worldwide fallout of the pandemic has led to a number of countries evaluating their dependencies and contemplating ‘de-coupling’ and ‘de-risking’ in their strategies towards China, especially where global value chains are concerned. This has led to China vociferously reiterating the need to strengthen globalisation and the current white paper is no exception. It professes a “new type of economic globalisation”, which opposes protectionism and sanctions, of which it has been at the receiving end in recent times. Formation of plurilateral mechanisms like the Quad and AUKUS have accentuated China’s feeling of containment by the rest of the world and this is reflected in its opposition to these “cliques” in the white paper. China’s sensitivity to its form of professed democracy is also evident as it makes the cause for “common values of humanity” rather than a standard for democracy. China also makes common cause with countries that have a similar authoritarian approach to governance arguing that democracy cannot have one universally applicable model. The white paper also brings together all of China’s global initiatives, i.e., the BRI, GDI, GSI and the GCI as Chinese contributions towards building the “global community of shared future”.

Implications for the Global Order

China has grown to be a global player with an expansive footprint around the world. Its economic heft as the world’s largest trading nation and a manufacturing juggernaut has aided this expansion. Initiatives like the BRI, over the last decade have further consolidated this influence in many regions of the globe like South East Asia, West Asia, Central Asia and Africa. Its development aid along with the BRI has made China a preferred development partner in many countries of these regions. Its rapidly modernising military has accentuated security concerns, not just in its immediate neighbourhood but further afield in the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. Along with its increasing military strength, China has also become one of the world’s largest arms suppliers with countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Tanzania dependent on Chinese military equipment and platforms. These developments have sharpened China’s ambitions of becoming a major global power in tune with its centenary goal of “becoming a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced” by the middle of this century. Achievement of this goal is contingent on a favourable external environment which China assesses as turbulent and hence reform of the current international order is a necessity for the advancement of these ambitions. Xi’s desire to leave a legacy of a strong leader and a global statesman, alongside the pantheon of Chinese leaders like Mao and Deng, is clearly visible in his personal stamp on all of China’s recent global initiatives. Xi’s penchant for centralisation of control under his authority is apparent in the creation of the umbrella of the “global community of shared future” for all these initiatives including the BRI. Notwithstanding, this centralisation will allow China to leverage complementarity as also rationalise utilisation of resources for projects under these various initiatives.

The GDI has got a lot of traction in the UN as also in many countries of the global south, even as the Group of Friends forum pushes for further expansion. Unlike the BRI, which did not find inclusion in any major narrative at the UN, the dovetailing with the UNSDG 2030 will ensure that the GDI becomes an integral part of UN programmes in this direction. Unlike the BRI, the scope of projects under the GDI seem to be much smaller, in term of size and funding, enabling more projects to be planned across a wider geographical expanse. All the priority areas of the GDI, viz, poverty alleviation, food security, pandemic response and vaccines, financing for development, climate change and green development, industrialisation, digital economy and digital connectivity, are largely in the socio-economic domain, which appeals to much of the global south. This attraction is further accentuated for these countries especially when considering the options, other than China, for industrialisation and digitisation, which are either more expensive or out of reach due to various reasons. Moreover, the smaller budgets of these projects may serve to inoculate countries against the inimical fallouts as experienced in some projects of the BRI. Further, the synergy created between the BRI and various national development plans of countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Kazakhstan and others will also open up avenues for the GDI to make headway.

The GSI is China’s attempt to become a global player in the security domain, an area which has been largely dominated by the US after the end of the Cold War. The recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan and perceptions of a reluctance for its engagement in West Asia seem to have given further impetus for the Chinese initiative. Nevertheless, Chinese proposals like the ‘five-point proposal on realising peace and stability in the Middle East’ have not received the kind of traction that China may have wanted. In part, it is possibly due to the lack of credibility in China’s motives in this region. Another factor could be the absence of Chinese hard power in this part of the world. However, the Chinese mediation in the Saudi-Iran rapprochement is being seen as a sign of China’s increasing stature in West Asia. China’s actions in the South and East China Seas, seem to detract from its professed ideas of security in this proposal and create doubts, if not concerns, about its motives behind the GSI. Consequently, countries in South East Asia have not yet supported this proposal as have some others like Pakistan. Notwithstanding, China has also been successful in convening a peace conference in the Horn of Africa though definitive outcomes of this engagement are yet to be seen. China has an ongoing commitment under the Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) for “undertaking” peace and security projects in Africa and for supporting African countries’ efforts towards regional security. The Lancang Mekong Cooperation (LMC) forum is another mechanism through which China undertakes sub-regional initiatives for security. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) also has a security dimension with China steering some initiatives. Reports of a Chinese base in Tajikistan, with the Chinese undertaking joint border patrols with the Tajiks, near Afghanistan, have also been confirmed by sightings. The Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, had proposed a ‘Five Point Initiative on Achieving Security and Stability in the Middle East’ during his trip to West Asia in March 2021 along with the establishment of a regional security mechanism, specifically for ensuring safety of oil facilities and shipping lanes. During a visit to Sri Lanka in January 2022, Wang Yi proposed a forum for the development of Indian Ocean island countries. Moreover, a large number of small countries, all UN members, in Africa remain enamoured of the Chinese model of authoritarian governance and have subscribed to a number of technology-oriented Chinese security solutions for various problems. This bloc, some of whom are already members of the GoF of the GDI, are likely to support China in pushing the GSI at the UN. Much of the western world, especially the US and its allies and Europe, as also South East Asia are likely to remain wary and even concerned about Chinese intentions in the security domain, though the translation of these concerns into action does not appear imminent.

The GCI, on the other hand, is relatively nascent and lacks an action plan at this stage, though it will have to be watched closely. Nevertheless, China’s aspirations of becoming a global cultural power will ensure outlining of clear objectives for fulfillment of these, though attraction for Chinese culture still remains minimal in most parts of the world. Emerging domains of technology like digital communication and telecom, artificial intelligence and the like have seen a profusion of Chinese equipment and projects in many regions of Africa and Asia. Coupled with Chinese initiatives like the Global Initiative on Data Security, the scope for greater acceptance of Chinese standards in these regions has the potential for creation of Chinese spheres of technology which could compete with existing mechanisms, creating another dimension of competition in the world order. Another aspect of Chinese intentions to reform global governance lies in the domain of international finance and economics, part of which the BRI was intended to address. While that domain has not been addressed in this paper, it is important to remain cognisant of Chinese actions, as much of those will be complementary to the “global community with a shared future”.

The “global community with a shared future” is China’s unequivocally stated strategy for “reforming and improving the international governance system”, undoubtedly with Chinese characteristics. It has already found its way into a large number of statements at the bilateral also multilateral fora and will likely find increased resonance in the global south. The Chinese propensity to translate such visions into a clear action plan, as witnessed with the BRI, should be a signpost to take cognisance of these ambitions and guard against its fallout.

References

[1]President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs, 29 Nov 14. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1215680.shtml. Accessed on 17 Jan 20

[2]President Xi Jinping’s speech on ‘Working Together to Forge a New Partnership of Win-win Cooperation and Create a Community of Shared Future for Mankind’ at the 70th Session of the UNGA, New York, 28 Sep 15.

[3]President Xi Jinping’s speech at Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs, 24 Jun 18. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-06/24/c_137276269.htm. Accessed on 17 Jan 20

[4]Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 13 Sep 23. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjbxw/202309/t20230913_11142010.html (Accessed 15 Sep 23.)

[5]Yang Jiechi State Councilor of the PRC at the Opening Session of the 51st Munich Security Conference, 07 Feb 15.https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/201502/t20150207_678273.html. Accessed 15 Sep 15.

[6]China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis, 24 Feb 23.

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202302/t20230224_11030713.html. Accessed on 27 Feb 23

[7] ‘The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper’, The Foreign Ministry of the PRC, 21 Feb 23. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202302/t20230221_11028348.html. Accessed on 21 Feb 23

[8]Xi Jinping Attends the General Debate of the 76th Session of the UNGA and Delivers an Important Speech, 22 Sep 23.https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202109/t20210923_9580033.html. Accessed on 26 Sep 21

[9] ‘Building Consensus and Synergy for a Bright Future of Global Development’, Address by State Councilor Wang Yi at the Sustainable Development Forum 2021, 26 Sep 21.

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202109/t20210926_9580016.html. Accessed on 26 Sep 21.

‘Global Development Initiative — Building on 2030 SDGs for Stronger, Greener and Healthier Global Development (Concept Paper)’, The Foreign Ministry of the PRC.

https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/topics_665678/GDI/wj/202305/P020230511396286957196.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 22.

[10] ‘Progress Report on the GDI 2023’, The Foreign Ministry of the PRC, 20 Jun 23. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/topics_665678/GDI/wj/202306/P020230620670430885509.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 23.

[11]Xi Jinping Attends the CPC in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting and Delivers a Keynote Speech, Foreign Ministry of the PRC, 16 Mar 23.

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202303/t20230317_11043656.html. Accessed on 23 Mar 23

[12]Chapter 10 - Develop Advanced Socialist Culture and Enhance National Cultural Soft Power, The Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China and the Outline of Long-Term Goals for 2035, The State Council of the PRC, 13 Mar 21. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm. Accessed on 16 Mar 21

[13] ‘Deepening Exchanges and Mutual Learning Among Civilizations for an Asian Community with a Shared Future’, Keynote Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping at the Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations, Foreign Ministry of the PRC, 15 May 19. https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/90755.html. Accessed on 20 May 19.

[14] ‘A Global Community of Shared Future: China’s Proposals and Actions’, The State Council Information Office of the PRC, September 2023.

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202309/t20230926_11150122.html. Accessed on 28 Sep 23

[15] ‘Work Together to Build a Community of Shared Future for Mankind’, Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping, 18 Jan 17. Foreign Ministry of the PRC. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-01/19/c_135994707.htm. Accessed on 19 Sep 23

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://www.globaltimes.cn/Portals/0/attachment/2023/2023-03-16/5d99d52d-ae11-41e0-821f-f18845b84f1e.jpeg

Post new comment