From the two successive visits of Kamikawa and Kishida to the ASEAN region in quick time, it transpires that Japan now accords extra importance to the region as strategic environment has turned volatile. Japan’s economic engagement with the countries in the bloc is well known. Now there is a serious security dimension to this relationship that Japan finds compelling to build. In particular, from Japan’s recent defence relations with two major countries in the bloc – Vietnam and the Philippines, it becomes evident that Japan has prioritised boosting security network with the ASEAN countries.[1] Even Kishida’s predecessor Yoshihide Suga chose Southeast Asia for his first overseas visit when he became Prime Minister.

Whys is that so? As said, the sole objective is to help maintain regional peace and stability, which have come under stress recently and this adversely impacts the economies of all the countries in the region. A cooperative approach by major stakeholders can help contribute to the maintenance of the existing equilibrium.

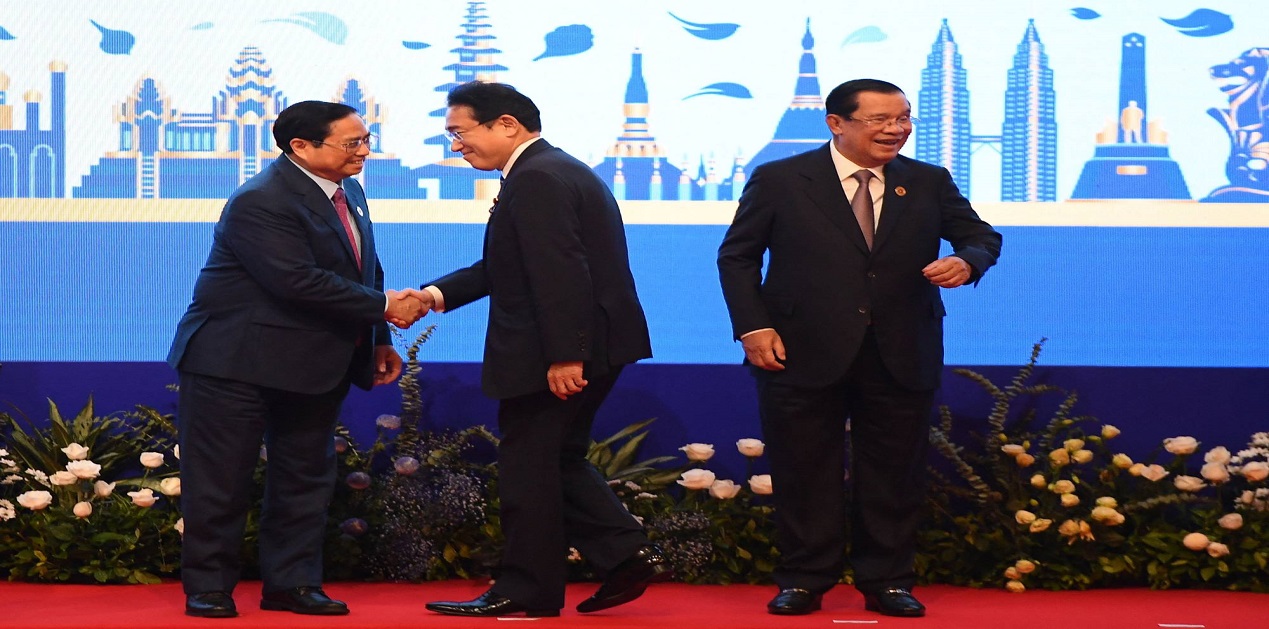

When Kishida chose to make a three-day visit to Malaysia and the Philippines from 3 to 5 November 2023, it transpired that he was keen to strengthen Japan’s security and defence ties with these two countries in Southeast Asia. The visit shall also reinforce Japan’s recently launched military aid programme to these two countries. Both these visits were Kishida’s first to these two countries. Kishida probably felt that Japan’s security alliance relationship with the US is inadequate to stem China’s increasing military assertiveness and therefore thought to build and expand a network of security partners with some of the Southeast Asian partner countries to add heft to Japan’s existing security partnership with the US and to counterbalance China’s growing military might and assertiveness on many regional issues.

While in Kuala Lumpur, Kishida discussed with his Malaysian counterpart Anwar Ibrahim how to accelerate coordination for implementing Japan’s new Official Security Assistance (OSA) programme which was first announced in December 2022 during the release of the revised National Security Strategy. According to this, Japan shall provide equipment, supplies and infrastructure development assistance to partner countries in the Indo-Pacific region, mostly in the form of grants, not loans.

The primary objective of the OSA was to strengthen partner countries’ security and deterrence capabilities to “reinforce the comprehensive defence architecture so that China’s aggression against Taiwan and in South China Sea is deterred. The purpose was to create a more favourable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region. The security cooperation also included maritime cooperation, including through joint coast guard exercises. Kishida was aware that amid military modernisation by many countries in Southeast Asia in response to heightened regional tensions and Chinese assertiveness, Malaysia chooses a contrarian position. Malaysia is less focussed on acquiring capabilities to confront China on the high seas, possibly because of funding constraints and takes the position that territorial disputes with China should be solved diplomatically.

The launch of the OSA marks a break with Japan’s previous policy of avoiding the use of development aid for military purposes other than disaster relief. Bangladesh, Fiji, Vietnam and Malaysia are also among those being considered for the programme.

Whether Malaysia’s traditional emphasis is for cooperation with China when other bloc members are all stressed up and thus treated as neutral is difficult to say but consensus building process within the bloc could be difficult if all 10 members of the bloc are not on the same page when the region faces a common challenge.

Because of its limited naval and air capabilities, Malaysia feels incapable to stand up to China and prefers legal route to protect its interests. Malaysia is unable to deter Beijing from maintaining a near-constant coast guard presence for several years in the Malaysia-claimed waters near Luconia Shoals, where its state-owned Petronas has been exploring gas fields.

Kishida’s discussion with Ibrahim was probably intended to address this delicate issue. Kishida assured Ibrahim that the rest of the Asian nations would not tolerate attempt by any country attempting to unilaterally change the status quo and pledged to work together. Kishida visit to Kuala Lumpur was intended to influence Malaysia in changing its stance towards China. Kishida felt that Kuala Lumpur was tilting towards China because of its inability to stand up to China and therefore assured Ibrahim that Malaysia need not feel vulnerable to China’s maritime encroachment in the South China Sea. What was required was a common front to deal with this common challenge.

A similar narrative unfolded when Kishida landed in the Philippines and discussed China threat with Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Like Vietnam, the Philippines have also chosen a tougher position against China’s territorial ambitions. Though the Philippines won at the Hague international tribunal which dismissed China’s claims over South China Sea as invalid, China rejected the award. When Marcos Jr visited Tokyo in February 2023, he and Kishida agreed to begin talks on a reciprocal access agreement (RAA), a pact that provides the legal framework for greater bilateral security cooperation and expanding trilateral ties with their common defence ally, the US.

Tokyo has signed two similar agreements in recent years, one with Australia and another with Britain, both of which came into effect in 2023.[2] The new deal will mark Japan’s first with a member of the ASEAN. Philippines’ strategic location makes it crucial to maintaining regional security and stability as it is located relatively close to Taiwan and astride key maritime trade route. If Beijing chooses to use force against Taiwan, a regional conflict akin to Russia’s military operation in Ukraine could be very much thinkable.

What does an RAA mean? The RAA is a defence agreement that Japan has pursued with a handful of countries, serving as a framework for the country’s military and security operations and training with other nations. An RAA between Japan and the Philippines would allow Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) greater access to Philippine bases, potentially even rotational deployments, and facilitate joint military drills and other security operations such as joint patrols.[3] Once an RAA is concluded, it will become much easier for Japan and the Philippines to cooperate militarily and boost the deterrence effect against China and would provide Manila with more strategic options to counter Beijing’s growing assertiveness.

Such a pact would also make it much easier for the SDF to be deployed in the Philippines in times of emergencies, including natural disasters. A trilateral cooperation between the US, Japan and the Philippines would also help build a robust military posture against external threat. It may be recalled that the US and the Philippines reached a deal in early 2023 that gave access to the US to four additional military sites in the Philippines, allowing the US to substantially boost its defence postures in the disputed South China Sea and near Taiwan. Kishida also revealed that Japan would provide coastal surveillance radars via a grant worth $4 million, making Manila the first beneficiary of the OSA programme. Under a 2020 contract, Japan has already delivered the first air surveillance radar system to Manila.

Japan also offered to provide aid grants worth $6 million to Manila to purchase trucks, bulldozers, and other heavy equipment to repair transport networks and infrastructure damaged by natural disasters in Bangsamoro, an autonomous region predominantly inhabited by Muslims and marked by conflicts between militants and the Filipino military. Japan has also been financing the ongoing Metro Manila Subway and the North-South Commuter Railway projects, estimated to cost billions of dollars.[4]

The OSA program shall facilitate Tokyo in helping Manila improve its maritime law enforcement capabilities through port infrastructure development, technology cooperation, transfer of more defence equipment such as warning and control radars, and additional patrol vessels. As the first Japanese Prime Minister to address the Philippine Congress, Kishida remarked that Japan-Philippine ties are now “stronger than ever”. Kishida warned that the rules-based international order is under serious threat and therefore multilayered cooperation among allies and like-minded countries is needed to maintain this order.

Unlike his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte, Marcos Jr has taken a more assertive stance on territorial disputes with Beijing since coming to power in May 2022. In a clear departure from Duterte’s staunch pro-China policies, Marcos Jr has vowed not to lose “an inch” of territory in the South China Sea. In retaliation, Beijing has upped the ante by escalatory measures and indulged in collisions with Philippine resupply ships near the Spratly Island chain. Unless Beijing is reined in, it could escalate into a larger crisis and would inevitably draw the US in as a treaty ally.

Beijing is also irked that Marcos Jr suspended a military exchange programme with China and cancelled a series of development projects under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since coming to power. Beijing has also not taken kindly the OSA deal between Japan and the Philippines and criticises Japan that it has violated its self-imposed restrictions on exporting weapons and questions Japan’s claim of pacifism as providing defence equipment to Southeast Asian countries is contrary to its pacifism claims. Beijing sees the move by the two “semi-allies” suspiciously.

As regards Manila, it benefits from having as wide a coalition as possible supporting its military modernisation and providing diplomatic and economic support as it stands up to Beijing by feeling emboldened by the 2016 arbitration ruling by the international court that dismissed China’s claims as invalid and lacked historical basis. For Manila, multipronged external support is extremely important as its defence budget is only $5 billion, most of which is used to deal with ongoing Islamist insurgencies in Mindanao and Sulu. Therefore, support from Japan is always welcome for the Philippines.

As regards India, it welcomes these developments as it subscribes to a rules-based international order and strengthening of Japan-Philippines relations shall contribute to regional peace and stability, a policy that India endorses.

References

[1]Gabriel Dominguez, “Japan turns to Southeast Asia to boost security network”, The Japan Times, 5 November 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/11/05/japan/politics/fumio-kishida-philippines-malaysia-analysis/?utm_source

[2]Gabriel Dominguez, “Japan and Philippines agree to take defense ties to next level”, The Japan Times, 4 November 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/11/04/japan/politics/japan-philippines-fumio-kishida-raa-osa/?utm_source

[3]Jason Gutierrez, “Philippines, Japan boost military ties amid tensions in South China Sea”, 3 November 2023, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2023/11/mil-231103-rfa01.htm?_m=3n%2e002a%2e3755%2eon0ao069c5%2e3hmt

[4]Ibid.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/np_file_193568.jpeg

Post new comment