(Reading Part 1 of this article is a recommended prerequisite to gain proper understanding of the second part. The previous article took instances of Human Rights in PM Modi’s US visit and India’s response to it as an entry point to discuss the larger theme of Human Rights and American politics of immigration).

Human Rights and Immigration Politics of America against the Fallen ‘Utopias’

The narrative of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ has always been the engine of both colonialism and modernity whether the myth of catch-up development or the colonial ordering of history as ‘ancient’, ‘mediaeval’, or ‘modern’ serves the same purpose of creating a radical future-directedness. In Hegel’s description, America was already a “land of the future….It is the land of longing for all those who are weary of the historical arsenal that is old Europe”.[1] Many European thinkers like Hegel, Adam Smith and Karl Marx always had the preconceived notion of Europe being the ‘end of history’ (future for the world) in which they may have seen regions like India to be a ‘cradle of civilisation’. The purpose of such nations was merely to play their historical role in laying the carpet for the end of history to come, a tag which the West in modernity has in its sleeves.

In the 21st century, particularly after the Cold War the concepts of globalisation, modernisation, and westernisation have always appeared synonymous to Americanisation. How can one explain America's incredible success in its goal to become the key driver of globalisation? To answer this pertinent question, American studies scholar Ulfried Reichardt examines the American mindset, rooted in the American dream of presenting itself as the ‘golden door of the future’.[2]

The cultural trust on America as a land of the future has a particular history that begins with the first immigrants, the Puritans, to land on the coast of the ‘new world’. This American national imagination of being the land of the future directly relates to its politics of human rights and immigration politics. Until the 1980s, American culture followed a ‘melting pot’ model regarding immigration and national integration. The immigrants that fled to America, including those from Europe, had heterogeneous ancestries. How would they get accustomed to the new body politics in the promised land of America? It was through a ritual of ‘assimilation’, which included many practices that collectively could be called a melting pot. To fully integrate themselves into “One America,” the immigrants must ‘melt’ or abandon their cultural identities. This immigration ritual was not just executed by introducing common national symbols or change of clothes and language, but rather involved a systematic forgetting and condemnation of their own heterogeneous pasts. The price these migrants had to pay to avail the rights and progress of American promise was to convert from their ancient past to the modern future. Their heterogeneous identities that belonged to different nations were remembered by scary images of rights violations, poverty, oppression, lack of freedom, etc., back home. Of course, it was not easy to wash out their past identities to melt them towards an American identity. Hence, the immigration ritual of the ‘melting pot’ involved interventions that were required in the field of education, from kindergarten to schools to companies. Indeed the melting pot or assimilation process took a transitional time of two to three generations.

The above image which illustrates the idea of melting pot is from a 1908 play titled ‘The Melting Pot’ which tells the story of a Russian Jewish immigrant family in the United States.

The melting pot model successfully presented America as a ‘mother of exiles’ to the rest of the world. This is best articulated by a Jewish immigrant, Emma Lazarus, in 1883 through her sonnet called “The New Colossus” written about the Statue of Liberty: [3]

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The Wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me:

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

These words were later engraved on the base of the statue.

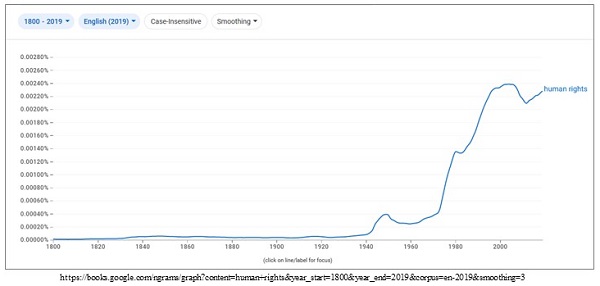

During the melting pot period, human rights were yet to emerge in the contemporary form. It was still associated with citizenship rights that America offers the rest of the world for their freedom. Therefore, even the usage and popularity of the term was minimal. The n-gram viewer below shows how less frequently human rights was used in printed sources published even after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was drafted in the 1940s. However, decades after UDHR, from the 1980s, we see a sudden rise or an explosion in the use of human rights. See below;

It was only post 1980s human rights emerged as a social movement transcending government institutions.[4] This transcendence aligns with the shift in immigration politics that was transformed from a ‘melting pot model’ to a ‘salad bowl model’.

The future-directed utopian march embedded in the melting pot model fell into a crisis as the world reached closer to the 1980s. Since then, the ‘future’ as a motivator has been less workable in the arena of politics. The future, which was associated with particular promises, ideologies and the nation-states, gradually lost its appeal. Aleida Assmann gives some obvious reasons to explain this disenchantment about the future, “resources of the future have been eroded by a number of complex challenges, such as the depletion of natural resources, the ongoing ecological degradation that accompanies technologically advanced societies (like the USA), climate change and water crisis…..along with demographic problems such as overpopulation and ageing societies, have fundamentally altered the image of the future.” (emphasis added).[5] Many surveys confirm that the rhetoric of progress has dwindled much unlike before in the public imagination.[6] The notion that “the world is continually improving” is now heavily problematised. This is because, unlike before, the idea of the future has shifted from being a venue of expectation and ‘happily ever after’ to a site of anxiety. Since then, the word ‘sustainability’ has taken over the privilege that the word ‘progress’ used to enjoy. The ‘fear of the future’ is often expressed when the lives of posterity are discussed. The project of rights has also remained close to the progressive developed world, like the US, with intensified resource extraction and ever-expanding fossil-fuel usage. While the political utopias vouch for egalitarianism and an evenly distributed world, it also implies an evenly ever-expanding fossil fuel usage, for instance, which is unsustainable.[7] While the unsustainability of the project is an issue, what is to be noted here is how the ecological crisis directly impacts the fall of political utopias and their broken promises about the future.

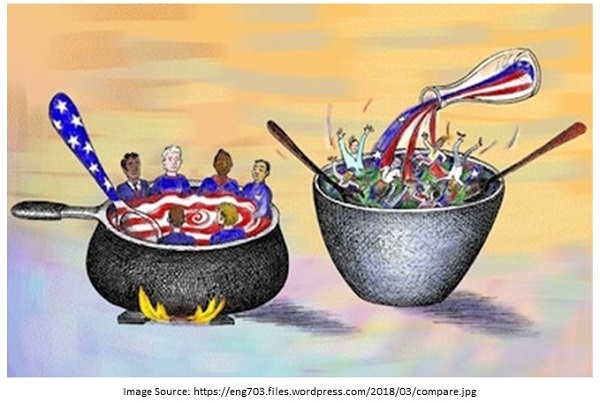

In short, the crisis was felt by the fall of Utopias promised by early political ideologies that are enclosed with citizenship rights and possibilities for immigrants. Ever since, rights as a slogan for democratic revolution have sounded less compelling. After the crisis, the ‘melting pot’ model was replaced by a ‘salad bowl’ model in America. In the era of the ‘salad bowl’ model, the concept of right served a different purpose, unlike before. An illustration of these two metaphors is given below;

In a salad bowl model, the assimilation is subtle, where identities are not visibly cooked or melted. Instead, identities are retained as they are, perhaps stronger and more explicit. In fact, forgotten identities were searched, dug up, and re-imagined. While the melting pot was more about choosing the future and forgetting the past, the salad bowl is backward-looking, identity-driven through history, and moral remembrance of the past. Categories like ‘minority’ and ‘ethnicity’, which hardly had a space in the melting pot model, take the central position in the salad bowl model. The communities that were not completely cooked into the melting pot came out to be visible firmly through the idea of the salad bowl around the 1980s in America.

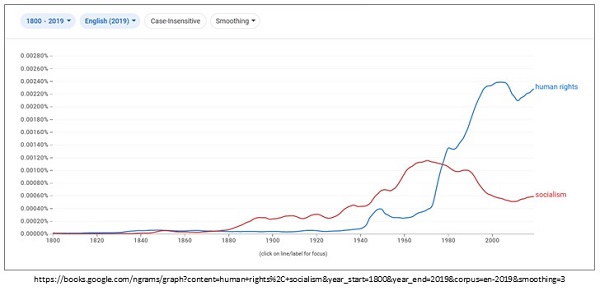

The period of 1980s also marks the period of decline of the Cold War and the rise of the category of human rights. As mentioned before, the contemporary form of human rights that transcends government institutions as a morality of the globe begins from here.[8] To demonstrate how the rise of human rights marks the decline of the Cold War, one can see in the following n-gram chart where human rights ascend from the point where socialism drops. See below;

Until the 1980s, even after the UDHR, the language of rights was significantly attached only to social citizenship, which was more concerned with the idea of a welfare state that provides protection and citizenship entitlements. This explains its lesser usage, unlike its contemporary mobilisational form, which transcends government institutions. In other words, during the ‘melting pot’ period, the category of human rights was yet to emerge as a ‘morality of the globe’.

Once the melting pot immigration model, along with the fall of political Utopias and the end of the cold war; the salad bowl model goes hand in hand with the proclamation of human rights. On January 20, 1977, Jimmy Carter began his presidency by embracing the United States’ absolute commitment towards human rights. In his words, “Because we are free we can never be indifferent to the fate of freedom elsewhere … Our commitment to human rights must be absolute.”[9] Prof. Samuel Moyn observes that this was a significant moment because before that, we didn’t know of any US President talking about human rights, except for Franklin Delano Roosevelt for a couple of passing references, which never gained much global attention. This point is noteworthy as it suggests the background of the United States’ self-understanding or claim of self-positioning as a ‘watchdog’ of human rights in the world, particularly after the Cold War. Republican presidents have embraced human rights ever since Carter brought them up, by connecting them to "democracy promotion" abroad. The impressive growth of NGOs from the US working around the world succeeded this period.

What necessitates the salad bowl model to peddle on human rights? Though Salad Bowl ideology is embraced much, the United States knows how damaging it may get. Because in that model, rather than a sense of commonality a sense of separate identities is embraced. In a melting pot model, there wasn’t a need to seek a sense of commonality and national identity. It was embedded in the process itself. However, the salad bowl had to be introduced after the collapse of the ‘golden door’ utopian imagery of the United States, where the distinguished identities of immigrants had to be acknowledged. Hence, in what sense would America retain a national identity in such a scenario? How would they cover up their political anxiety or manage their national integrity, which is in question? It is through a ‘moral positioning’ of the US through a mobilised form of human rights that is now spread worldwide after the 1980s as demonstrated above.

The Four Point Plan of President Truman after World War II in 1949 is well known, which states that the US must uphold a unique obligation to promote democracy and economic progress worldwide.[10] This global commitment and national utopian ideals in the 1980s of ‘Americanisation’ through the ‘melting pot’ began to get problematised. In such a crisis, how to make the world believe that America is a ‘force for good’ came as a bigger question. Many believe that American interventions to play the world’s policeman have created havoc, the price of which is paid by certain parts of the world today. Though the criticism of ‘American hypocrisy’ is in place, America has also successfully convinced many that it is hypocritical because it attempts to speak the truth! Nobody accuses China of being hypocritical because it is visibly authoritarian.

This way, the major success of America after the Cold War is to make the world believe that it is a ‘force for good’ in the world by scaring the world with worse alternatives to their hegemony and power. We tend to imagine that in the absence of America, powers like China would take over, and the world would collapse; therefore, America is a force for good. The biggest success of America after the Cold War is perhaps that it taught the world to imagine that the world can function only under its watch. In other words, authoritarian regimes and human rights violations are both required for the US to demonstrate its moral obligation to steward the world, just as poverty in the third world was a prerequisite for the first world to perform philanthropy around the world. What defines American nationalism today under the ‘salad bowl’ model is by selling this collective moral obligation to the world. Especially after the 1980s, the nationalism of America and its spirit is guided by this moral obligation for which the tool of human rights became highly significant for America.

Conclusion & Further Inquiries

In the standard story on the intellectual history of Human rights, it is viewed as a monolith virtue that the modern world has received as an outcome or culmination of a long-standing intellectual legacy of enlightenment. The politics of human rights has become so mobilisational that any attempt to explore the genesis of the idea, and its evolution is viewed as strange.

While the underlying notion of rights remains the same, the contemporary form of human rights that emerged after the 1980s has a slightly different direction and purpose distinct from the era before. The cold war period of the 1980s is marked by the collapse of the future-oriented Utopian political ideologies of the world. Since then, the early story of America, its citizenship rights, other promises, and its imagery of being the ‘golden door’ for the future has seemed less compelling. In other words, those ideas that were considered fundamental to America’s national imagination were at stake. This had a significant impact on its immigration politics that followed a particular pattern from its beginnings in Puritanism, through the Enlightenment. This early immigration politics, which is expressed through the metaphor of the ‘melting pot’, is replaced by a ‘salad bowl’. The salad bowl immigration politics, as it is demonstrated in this essay, necessitates the US to convert human rights into a more mobilised form by transcending government institutions and political boundaries, unlike before. This necessity is coming out of an anxiety of fallen utopias in its backyard, which puts the national integrity and the foundation of ‘mainstream America’ at stake.

During Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit, the topic of human rights was raised directly and indirectly against India and its democracy multiple times. This article took that instance as an entry point to discuss how deeply human rights are related to America’s immigration politics, integrity, imagination, national imagination, and security. Therefore, when India participates in the politics of human rights as US-led geopolitics necessitates it, it must be aware of the background story in order to be conscious. This is because unconscious responses can become counter-productive, which is exactly what the US desires from countries like India in their engagement with global human rights politics. As an argument, it would be better to close this article by saying that no amount of defensive justification can ‘prove’ India has good standards in human rights and is not an ‘illiberal democracy’. The very reason why human rights politics in its contemporary form exist is not primarily because India or any other country is systematically discriminating against its subjects. Instead, it has to do with America’s own political anxiety and concerns about its imagined nationalism, which are at stake due to the crisis of certain nationalist ideas and events in their past. The argument is not to suggest that India or any country as a society shouldn’t be unconcerned about its problems. But such concerns shouldn’t come as an uncritical eagerness to respond or be accountable to America's questions on human rights. Simply because the contemporary politics of human rights in America primarily exist as a result of their own nationalist concerns and internal political anxiety.

In the subsequent sequels possible for this essay, the author would like to explain the theological tropes underplayed in immigration and human rights politics in the United States. The above mentioned future-directedness and moral obligation in the American mindset is often reductively explained as some kind of ‘superiority complex’ driven by racism or American nationalism. However, on a closer look, it appears that such cultural constructs in America could be understood only by understanding the theological idea of ‘heathen’ or the ‘heathen world’, which needs help or is required to be saved. In this particular way Americans were culturally learned to look at the world. It is possible to explore how the broad umbrella category of heathen, which covers many parts of the world, continues to be the major trope. Hypothetically, America’s politics of immigration and human rights are mere manifestations of the same in today’s times.

References

[1]G. W. F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History, trans. J. Sibree (New York: Dover, 1956), 86–87

[2]Ulfried Reichardt, “The ‘Times’ of the New World: Future Orientation, American Culture, and Globalization,” in REAL 19 (Tübingen: Gunter Narr, 2003).

[3]Read on “The New Colossus” https://www.nps.gov/stli/learn/historyculture/colossus.htm Acessed July 17, 2023.

[4]Moyn, Samuel. Human Rights and the Uses of History. United Kingdom: Verso Books, 2014. p.8

[5]Assmann, Aleida. Is Time Out of Joint? On the Rise and Fall of the Modern Time Regime. United States: Cornell University Press, 2020. P. 4

[6]Werner Mittelstaedt, Das Prinzip Fortschritt: Ein neues Verständnis für die

Herausforderungen unserer Zeit (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2008). Cited via Assmann, Aleida. Is Time Out of Joint? On the Rise and Fall of the Modern Time Regime. United States: Cornell University Press, 2020.

[7]This argument is much elaborated in the works of Dipesh Chakraborty. See for instance, Chakrabarty, Dipesh. The Climate of History in a Planetary Age. United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

[8]Moyn, Samuel. Human Rights and the Uses of History. United Kingdom: Verso Books, 2014. p.8 p.69-86

[9]See the Inaugural Address of Jimmy Carter here: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/carter.asp Acessed July 17, 2023

[10]See about Point Four Program here

https://www.britannica.com/event/Point-Four-Program Acessed July 17, 2023

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://sjhexpress.com/feature/2023/03/01/immigrant-students-share-experiences-life-at-home-moving-education/#photo

Post new comment