Xi Jinping’s three-day visit to Moscow, 20-23March, his first abroad in his third term as China’s President, evoked considerable interest. Two joint statements and a dozen bilateral cooperation documents were signed. Xi’s personal equation with President Putin- both leaders referred to each other as ‘dear friend,’ was apparent. Their discussions on the Ukraine conflict in the context of the Chinese peace plan and whether both countries would further deepen their military, economic and energy cooperation were closely scrutinized.

There were varied assessments. Some analysts felt that Russia-China relations were now stronger than ever before; others felt that Russia had become a junior partner or a vassal of China. One scholar said that the Russia- China partnership was now the ‘most consequential undeclared alliance in the world.’ These assessments, mostly from western analysts also permeated expert thinking in India. So, what do we make of Russia-China relations after Xi’s visit?

There is no doubt that Russia’s relations with China have been better in the last twenty years than in the last two hundred. The collapse of the Soviet Union helped remove the ideological edge to their conflict. The settlement of the border dispute and the signing of a Treaty of Good Neighbourliness and Friendly cooperation in 2001 turned a new page. The coming of President Putin to power in 2000 added an element of stability and predictability for China, whose leaders from Jiang Zemin to Xi have followed a steady path of deepening ties with Russia. The sharp deterioration in Russia’s relations with the West, mostly over Ukraine since 2014, has provided strong tailwinds for the Russia-China partnership.

In the 1990s, China depended on Russia for high tech military equipment but the peak of Russian exports was reached in the mid-2000s, over 15 years ago. China started supplying some arms to Russia in 2017 and is now a major supplier of dual-use machinery and equipment critical for the Russian defence industry. Russia deploys about a third of its nuclear-armed combat ready forces in its Far East military district against China; there are reports some of these units have been temporarily deployed west for the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. Russia and China are co-developing heavy lift transport aircraft. Russia is aiding China in building early warning radars to detect American missiles launched from the Pacific Ocean, whose signals will be shared with Russia as well. Both countries have conducted several military exercises, bilaterally and with other countries also in the context of SCO and joint air patrols of their nuclear-capable aircraft in the international airspace between ROK and Japan. While international attention was focussed on whether Chinese arms supplies would be provided to Russia for its conflict in Ukraine, the Summit provided no indication that China was prepared to provide such assistance, yet.

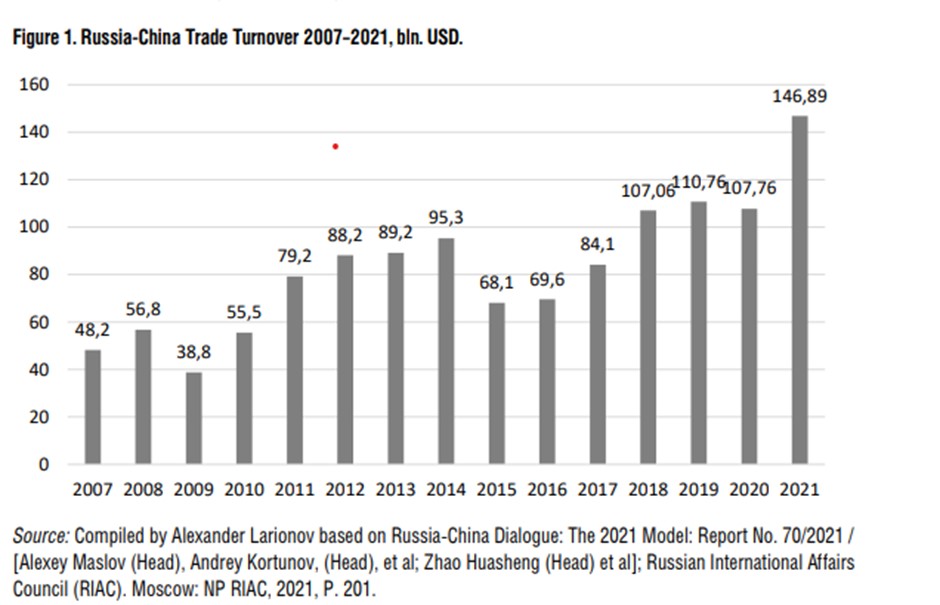

In 2022 bilateral trade between Russia and China grew by almost 30% reaching 190 billion USD with Russia gaining a trade surplus of 38 billion USD. This is unlike the trade basket between India and China – of the total of almost 140 billion USD China has a trade surplus of 100 billion USD. To put matters in perspective, the total trade in 2022 of the United States and the EU with China was more than 1.4 trillion USD. It is easy to exaggerate the political significance of Russia-China bilateral trade but when seen in context, the picture is somewhat different. The following trade figures published by the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC report 78/2022) provide the trade growth between Russia and China for the period 2017 and 2021.

The growth trajectory is positive but not exceptional. Bilateral trade has boomed due to China’s large market for Russia’s exports, especially oil, gas, commodities, agro and marine products. Russia’s turn towards the East accelerated after the imposition of western sanctions following Russian incorporation of Crimea in 2014, which China has not recognized. Major investments in oil and gas pipelines, particularly Power of Siberia pipeline made China, Russia’s most important energy partner in the east. Imposition of western sanctions has only increased China’s importance in Russia’s energy export basket. It is significant that agreement was not reached during the Summit on the pricing of Russian gas supplies through Power of Siberia 2 which will transit Mongolia before reaching China. While China has been seeking long term supplies at concessional rates, Russia has so far has been reluctant to be tied down to an energy arrangement that wholly favours China. If India was an alternative customer, Chinese advantage as a monopoly customer of Russian energy – the result of Europe cutting energy links with Russia under US pressure following the sanctions imposed after February 2022- would correspondingly decrease. Russian gas supplies to China currently are 55 bcms; until last year Russia had the capacity to supply to the EU more than 270 bcms of gas. The question to ask – where will that excess gas now go? This is a golden opportunity for India to look at a new energy alliance with Russia for long-term preferential gas/LNG supplies to ensure India’s energy security. Russia’s cooperation with China and through BRICS and SCO on de-dollarization and finding alternatives to SWIFT have gained pace. The vulnerabilities of both countries to US financial pressure are not the same though both countries have a common interest in accelerating the process of de-dollarization, bilaterally, in oil trade with the Middle East and with the global south more generally.

The stalemated Russia-Ukraine war has become China’s geopolitical golden moment, as it has geopolitically weakened Russia, while an overextended US has got stuck in the quagmire of prolonged European security crisis. Xi is aware that he can pick and choose his partners on the global stage. Xi’s visit to Moscow was intended not to promote Russia’s interests but to secure his own against the background of Russia’s international isolation from the West. In this triangular equation, China senses it has the upper hand and is pressing forward its advantage. But is Russia conceding ground? The evidence suggests otherwise.

While the Summit optics were good, there was a clear gap in expectations. Russia made positive noises about China’s Peace plan, whose first point- respect for territorial integrity, which Russia cannot agree to with respect to its newly acquired provinces in Donbass, is in direct contradiction to its second point -legitimate security interests of states, which amounts to de facto accommodation of Russian interests. This contradiction cannot be resolved except on the battlefield as the main supporters of Ukraine still harbour the hope that Russian occupation of Ukrainian territory ought to be reversed through war and not at the negotiating table. Sensing that the Chinese peace plan is part of a broader global diplomatic offensive of China, Putin did not give a handle to Xi for the latter to gain leverage with the US or the EU on a possible peace settlement in Ukraine. This has not prevented Xi from milking his Moscow visit as seen in the long parade of European leaders lining up to visit Beijing in the hope that Xi can use his influence with Putin for Russia to scale back its war aims in Ukraine. There is little to suggest that Russia will do so on Chinese bidding. Russia will not forgo military gains in Ukraine to enhance Chinese global standing. Putin ordered the deployment of non-strategic nuclear weapons to Belarus just two days after Xi’s visit to Moscow, having opposed in the Joint statement the deployment of nuclear weapons beyond national territories.

The bilateral Joint Statement dropped the phrase ‘friendship without limits.’ Its inclusion in the February 2022 Joint Statement was widely misinterpreted as reflecting the true nature of their strategic partnership. It was a case of deliberate exaggeration which having served its purpose has been discarded. Russia is aware that China will not help it in any substantive way in its war with Ukraine which would be at the cost of its relations with the US and the EU. There is also a fundamental contradiction in Russian and Chinese interests - the more the US is bogged down in Europe, the more it is a strategic boon for China. Russian weakness and continuing US pressure on Russia’s peripheries is China’s god-sent gift- as it is best positioned to occupy space at Russia’s expense in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Black Sea and Central Asia. Russia’s ability to retain its influence will also depend on the outcome of the Ukraine war. Writing off Russia prematurely would be a mistake just as it would be to assume that Russia would play second fiddle to China’s interests.

There are risks in exaggerating the depth of the strategic partnership between Russia and China, often with the preferred conclusion that this is the best time for India to deepen its strategic embrace of the US. What if, the argument goes, Russia stops extending support for India’s defence needs in a future conflict with China? The expressed concerns include the inability of Russia to meet India’s defence needs and buckling under Chinese pressure to abandon its previous policy of support for Indian interests. There appears also to be an unseemly haste among some analysts in promoting the line that India should see the writing on the wall, distance itself from Russia and seek so-called external balancing with a deeper alignment with the US bilaterally, with virulently anti-Russian countries such as Poland and the Baltics and through likeminded groupings like the Quad. Embedded in these fanciful assessments is a deep-seated cognitive bias against Russia and a deep yearning to pivot towards America, neither of which by themselves add up to sensible strategic policy. In an age of multipolar opportunities, limiting India options to those of a bygone unipolar era is self-defeating. Such assessments do not serve India’s interests well.

On the key question of Russian weakness, much will depend on the outcome of the Ukraine war. If current indications are anything to go by, Russia is expected to gain the upper hand on the ground, though accurate predictions are difficult to make. The Russian defence industry is expected to emerge larger and better funded producing battle-tested modern equipment in a few years’ time. China’s current advantage with respect to Russia is therefore not open ended and it is highly unlikely that Russia will be willing to pay long term geopolitical costs because of its current difficulties. Russia has seen India as an indispensable pillar of stability in Asia, as a counterbalance to China. This factor in Russian policy predates a similar factor in current US policy by several decades.

On the other hand, for different reasons, it is China and the US that have a mirror interest in the weakening of the India-Russia defence partnership – one to reduce India’s defence potential and the other to move into the defence market vacated by Russia. Amongst our foreign partners, Russia is still the best positioned to contribute to India’s Make-in-India defence programme as there is a previous history of cooperation. Its current weakness affords openings to secure better deals including on cutting edge technologies, not available elsewhere. Given India’s inventory management requirements with Russia going forward many decades, the continuing vitality of our relations with Russia would add leverage to our dealings with other major defence partners including the United States and France. In any case, with a huge boost in defence budgets and a massive expansion of the Russian defence industry, spares supply to our armed forces will improve sooner rather than later. Therefore, the nervousness anxiety in some sections to cut the Russia connection is not only misplaced but also self-defeating. In the long term, we should reduce our dependence on Russian armaments but not at a pace dictated by others.

The current geopolitical conflict amongst the big powers shows no sign of early settlement. The world’s foremost maritime power- the US, is locked in conflict with two of the major continental powers on the Eurasian continent. In the process it has tightened its grip on its allies on the periphery, in Europe, Japan and Australia but elsewhere, including in the Middle East and Africa its influence is waning, whetting China’s global ambitions. The military capacity and geopolitical competence of the US to sustain a prolonged dual containment policy with both Russia and China is under serious doubt even as the US gets overcommitted to an expanded NATO.

We are witnessing an emerging multipolarity that is contested rather negotiated, fought through military means and other forms of conflict such as the US Chips Act which is akin to an open declaration of a technology war. Our policy should be one of engagement with all but exclusivity towards none. Just as we get no joy out of Russian weakness on the Eurasian continent, we have nothing to gain from US overextension of its security commitments in NATO or its domestic divisions at home. Both tendencies need urgent correction. In this age of machine learning, massive energy and supply chain transitions, our America relations are vitally important. Even apart from our defence and energy ties, our Russia relationship is indispensable for a viable continental policy on the Eurasian landmass to face the China challenge.

China is a challenge like no other, especially now that it is on a geopolitical offensive globally, sensing an opportunity provided by the miscalculations of the other two big powers. But this is a challenge that will be with us for several decades. Strategic confidence rather than strategic anxiety is needed. It would be a mistake to see the China threat through the security prism of other big powers. China is a threat but not in the same way to every country. As such it is important to avoid an ‘Americanisation’ of our China policy, even while we have an interest in coordinated and not integrated deterrence against Chinese geopolitical assertions.

In conclusion, the risks of three exaggerations need be highlighted; the risk of exaggerating the strategic convergence of Russia’s relations with China; second, the risks of exaggerating American capacity, along with its allies in Europe and Asia for a prolonged dual containment strategy against Russia and China simultaneously; third, the risks of exaggerating the convergence of our security interests with that of the US in facing the China challenge. It is a sad comment that these three exaggerations are in wide circulation in our strategic discourse with little regard as to their attendant risks. The need has never been greater for a dispassionate analysis of global trends, from our perspective and rooted in our interests. India cannot become a great power through borrowed ideas or borrowed strength. In framing our own assessments and pursuing our own interests, it is vitally important to assess global trends accurately. In global politics, the only thing that is worse than weakness of power is weakness of thought that is necessary for its pursuit.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://c.ndtvimg.com/2023-03/f0sktdno_xi-jinping-putin-afp_625x300_22_March_23.jpg

Post new comment