Introduction

Over the last decade, the concept of blue economy, which refers to sustainable economic development through proper utilization of marine resources, has become widespread including in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The Indian Ocean covers more than 70 million square kilometers of area. It is surrounded by 38 countries and an estimated one third of the world’s population resides in them. While the blue economy encompasses a number of key economic sectors such as fisheries, aquaculture, shipping, tourism, minerals, oil and gas, maritime transport, etc., the fisheries sector remained arguably the most important as it is a key source of food and livelihoods for coastal communities. However, the sector is now confronting numerous challenges owing to climate change. That includes warming waters and changing ocean chemistry. The Indian Ocean in particular is warming at an alarming rate and it accounted for more than 30% of the heat content increase in the global oceans over the past two decades. That has impacted fish distribution, abundance, stocks, and diversity. Furthermore, climate change interacts with other human stressors such as overfishing, habitat destruction, and marine pollution. Thus, the future is dire for the Indian Ocean’s fisheries resources and for the millions of people who are depended on it for food and livelihood. This essay will examine the salience of blue economy in the IOR. Special emphasis is given to the fisheries sector as it is the backbone of food security, livelihood, and economic development for a number of countries in the region, developing ones especially. The potential impact of climate change on this critical economic sector is also analyzed.

The Concept of Blue Economy

The world’s oceans make up more than 95% of the Earth’s biosphere and deliver significant services essential for supporting all life forms. They regulate global climate and temperature, provides oxygen, absorbs carbon dioxide, and recycle nutrients. A number of economic activities such as ports, shipbuilding, tourism, fishing, offshore oil and gas production, global maritime trade, etc. are also dependent on the oceans. Resources of the oceans have been appropriated by humankind since the dawn of civilization. Dwindling terrestrial reserves of key resources such as oil, gas, minerals, etc. over the past few decades further resulted in a rush to extract them, often unsustainably, from the ocean. The flawed belief that oceans are an infinite sink with unlimited resources is partly to be blamed for this. However, there is now a growing realization of the need to sustainably utilize ocean resources for optimum economic development so that healthy ocean environments can be maintained over the long term. The concept of blue economy, which broadly views oceans as shared development spaces, has gained increased attention of countries around the world. The concept was first introduced during the “Rio+20” UN Conference on Sustainable Development that was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2012. The conference defined “blue economy” as “a marine based economic development that leads to improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities.”[1] The issue was mainly put forth by the coastal and island countries who advocated the need to recognize the significant role played by oceans for humanity and how the blue economy approach is better suited to their constraints and circumstances. It also aligned with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); goal 14 in particular that is concerned with the conservation and sustainable utilization of the oceans, seas, and marine resources within for sustainable development, especially in international waters. In short, healthy marine ecosystems contribute to more productive economies. As such, it is imperative that marine resources be used sustainably and with great care.

Beyond the UN’s definition of blue economy, there also existed several other definitions. For example, the World Bank defined blue economy as “the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, jobs, and improved livelihoods while preserving the ocean ecosystem’s health.” And according to the Commonwealth of Nations, blue economy is “an emerging concept which encourages better stewardship of our ocean or ‘blue’ resources.” The European Commission on the other hand defined it as “all economic activities related to oceans, seas, and coasts.” Broadly speaking, blue economy is an approach that seeks to balance conservation and resource extraction when developing ocean-based economies. The emphasis is on a sustainable development framework that encompasses ocean values and services while also making it part of the decision-making processes. In this way, countries, developing and underdeveloped ones in particular, could harness the benefits of marine resources and services in an equitable manner. As the UN has reiterated, the blue economy paradigm is one that aims to promote economic growth, preservation or improvement of livelihoods, ensure social inclusion, while simultaneously securing environmental sustainability of the oceans, seas, and coastal areas. While at the national level, it envisages inclusive jobs, opportunities and growth for all, social and gender equity, at the international level, there is promotion of equal rights of all countries to resources in the high seas.[2]

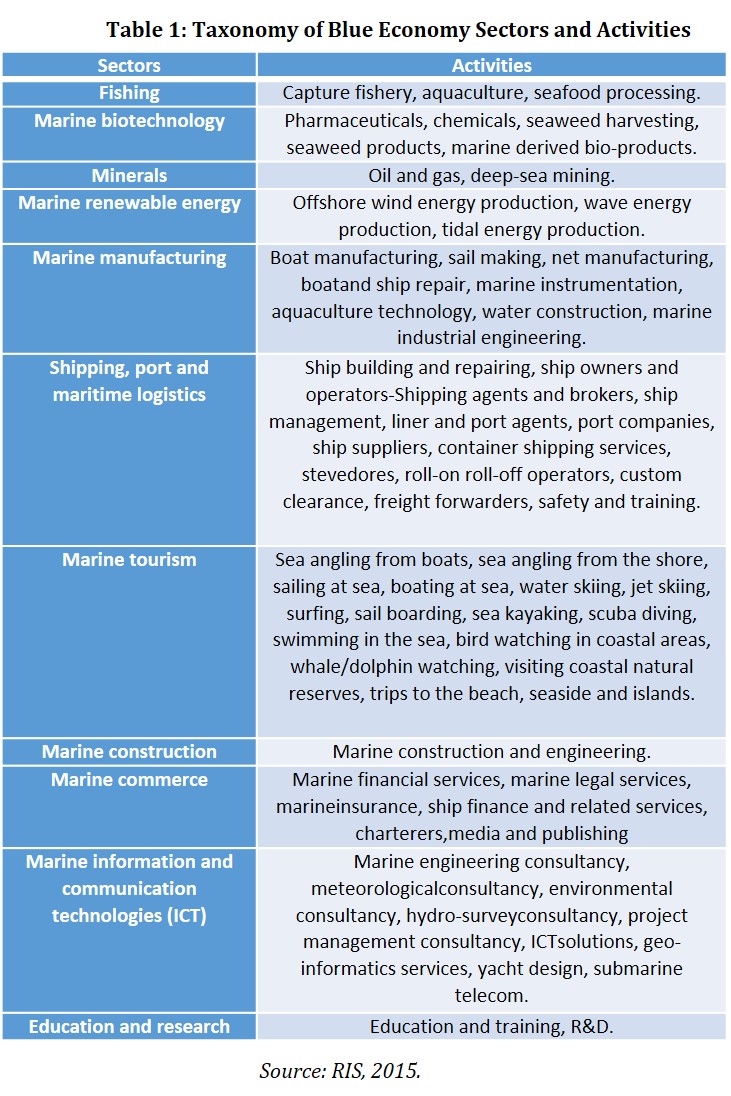

As regard to the components of blue economy, some scholars view economic resilience, sustainability, community participation, technical capacity, and institutional integration as key factors.[3] Others however consider legal resource management, monitoring reforms, and good governance systems as major factors that support blue economy at the national level.[4] A focus on blue economy opens up various opportunities in emerging and existing sectors. Fisheries, aquaculture, maritime transportation (shipping and port facilities), coastal tourism, marine energy, and deep-sea mining are some of the key sectors of blue economy.

Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR)

The geopolitical and economic pivot of the twenty-first century is said to be centered on the IOR. The region, which for centuries has been the hub of global trade and commerce, is widely recognized as moving away from being an “Ocean of the South” to an “Ocean of the Centre” and an “Ocean of the Future.”[5] The Indian Ocean covers a vast area of more than 70 million square kilometers and is bordered by more than 30 countries most of them are developing and emerging economies. It connects regions such as East Asia, South-East Asia, South Asia, West Asia, and East Africa to each other. Most importantly, the resources of the Indian Ocean are the key to the survival of countries that surround it. The dominant economic sectors among countries of the IOR are fisheries and aquaculture, tourism, port infrastructure and facilities, shipping, and offshore oil and gas. Countries such as Sri Lanka, Seychelles, Mauritius, and the Maldives are global tourism hotspots. India and Australia are the key players in the offshore oil and gas sector whereas South Africa and Mozambique have also explored their substantial oil and gas reserves in the Indian Ocean.[6] Meanwhile, deep sea mining, offshore renewable energy, and marine biotechnology have also emerged as important growth sectors. The Indian Ocean also holds immense potential for deep-sea mining in particular. The ocean floor is littered with critical minerals that are crucial for manufacturing clean and renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels, and electric car batteries. Besides, many of the world’s largest shipping lanes passes through the Indian Ocean and ship movements have increased manifold in the last few years. The strategic choke points, especially the Malacca Straits, the Strait of Hormuz, and Bab-el Mandeb are crucial to global maritime oil trade and are heavily trafficked.

The Indian Ocean however, has been subjected to resource overexploitation and marine pollution. It is also increasingly affected by climate change. Hence, an approach such as blue economy has become salient as it could help balance conservation and resource extraction.[7] Coastal and island states have been at the forefront of recognizing the real development potential of resources of the Indian Ocean and they have advocated for blue economy after the concept was articulated at the Rio+20 Conference in 2012. Since then, blue economy has become a major discourse among the countries of the IOR who are also part of the leading regional organization, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). The IORA ‘Blue Economy’ Declaration of 2014 was the first step for collaboration at the regional level for peaceful, productive, and sustainable use of the Indian Ocean.[8] In September 2015, the Declaration of the Indian Ocean Rim Association on Enhancing Blue Economy Cooperation for Sustainability was made during the conference on ‘Enhancing BE for Sustainable Development.’ The declaration underlined fisheries and aquaculture as the major sectors in the region. The IORA Council of Ministers meeting stated the relevance of blue economy issues including sustainable development and management of fisheries, encouraging tourism, harnessing renewable energy, and judicious exploitation of minerals so as to ignite growth and new opportunities, as well as ensuring food security and energy availability.[9] Towards this end, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Mauritius, and Seychelles are now moving towards establishing sustainable ocean economies. Bangladesh in particular has been leading the efforts to establish the Bay of Bengal Partnership for blue economy which would include India, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand. On the other hand, Seychelles and Mauritius have stressed blue economy as one of the main pillars of their economic development.[10] Seychelles even has a Ministry of Finance, Trade, and Blue Economy.

Importance of Fisheries Sector to the Blue economy of IOR

Globally, consumption of aquatic foods has increased especially in developing and less developed countries where a substantial proportion of their population is depended on aquatic foods for the daily protein intake in their diet. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 158 million tonnes of aquatic foods were consumed worldwide in 2019.[11] Of this, 72 per cent were consumed in Asia. Besides, around 58.5 million jobs were directly provided by the fisheries sectors in 2020 and an estimated 85 per cent of all fishers were in Asia. Aquatic products are also traded in some countries and thereby become another source of income. The fisheries sector has always been a key component of the economies of countries of the IOR. The region is rich in coastal and offshore seafood resources and is therefore a major global fishing hub.[12] For the populations living in the coastal areas, fish and other aquatic products have long been their main source of food as well as livelihoods. Island states such as Seychelles, for example, have one of the world’s largest rates of fish consumption in the world.[13]

Small-scale fisheries and subsistence fishing are especially important to IOR countries such as Sri Lanka and Tanzania. While commercial fishing is done predominantly by foreign vessels from Asia and Europe who focuses on tuna and other similar species, subsistence fishing by local coastal communities is the most common in the region. Although the local fishers do not receive high economic returns, fishing and related industries generate employment for many. Fisheries are an essential part of national economies and in connection with it, national security of littoral and island states of IOR. For some states such as Sri Lanka and Maldives who have Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) larger than their land area, fisheries and other marine resources are integral to their socio-economic development and food security. However, the fisheries sector is facing several challenges mainly due to anthropogenic factors. Overfishing, illegal fishing, habitat loss, and marine pollution are severely affecting the sustainability of fish stocks in the Indian Ocean. Additional stresses linked to climate change such as ocean warming, acidification etc., further exacerbated the situation. As such, there is an urgent need for better awareness of threats faced by the fisheries sector and to find ways to mitigate their impacts.

Climate Change and the Indian Ocean

Oceans all over the world are currently facing a number of environmental stresses including from climate change and that has increasingly endangered marine ecosystems. Across the vast Indian Ocean, human activities including coastal development are damaging coral reefs and other habitats. Pollution from industrial waste, agricultural runoff, and domestic sewage lead to discharge of toxic substances in the waters, eutrophication, and attendant hypoxia, thus killing marine flora and fauna.[14] Rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions alter the ocean’s temperature, chemistry, and overall structure which would result in changes in the evolution of marine species and interactions between them, negatively affecting the marine organisms as well as coastal populations.[15] The Indian Ocean and its coastal populations are especially vulnerable to climate change induced sea-level rise, ocean acidification, de-oxygenation, warming sea surface temperatures, and extreme weather events. Although these climate-related impacts materialize over a long period of time, they also present immediate threats. Observations show that out of the total greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere due to human activities, more than 90 per cent of the trapped extra heat is absorbed by the oceans, hence considerably helping in reducing global warming. However, as pointed out in the recent United Nations Ocean Conference in 2022 in Lisbon, Portugal, this phenomenon is not without negative consequences for ocean health, as it can result in ocean warming, ocean acidification, and ocean de-oxygenation.[16]

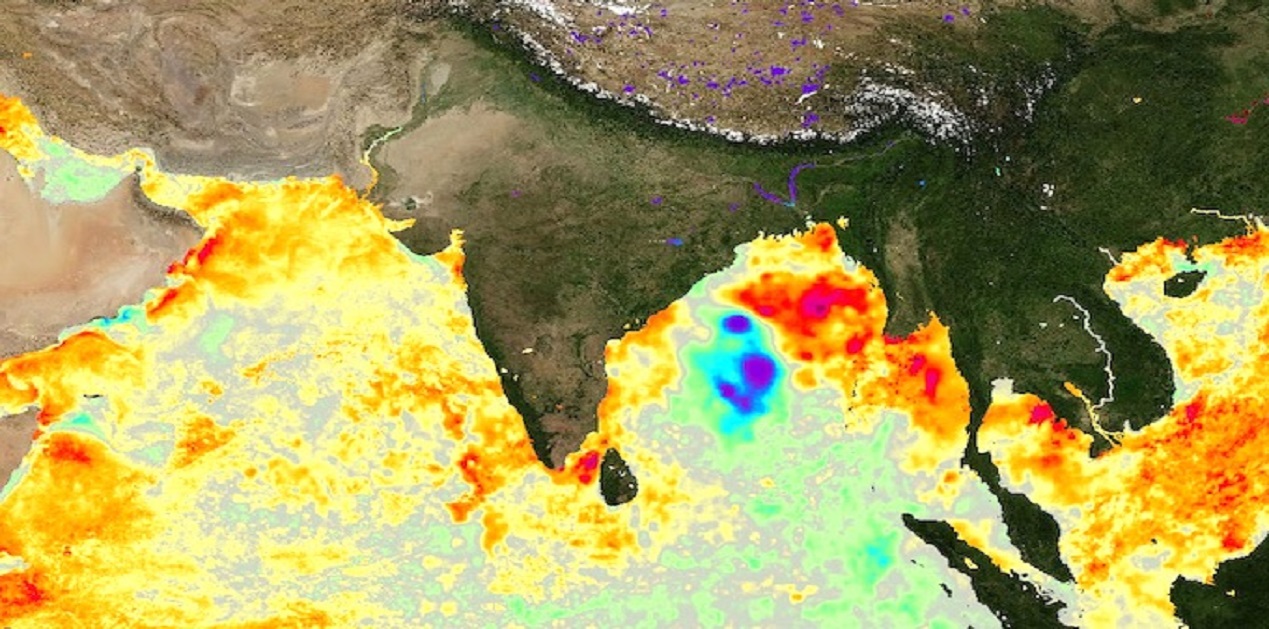

As carbon dioxide from the atmosphere dissolves into the ocean and sea waters, it forms carbonic acid and changes the oceanic chemistry by increasing acidity. Such changes can have notable biological and ecological implications over time. Climate change impacts have also been observed as contributing to decline in the ocean’s oxygen level, which would alter the distribution, composition, abundance, and diversity of marine life. Rising global temperatures have led to ocean warming and brought about a 0.7% increase in overall sea surface temperatures in this century alone. The thermal expansion of water, along with melting ice and glaciers have primarily caused rising sea levels as well. In the tropical Indian Ocean, the sea surface temperatures saw an average increase of 1 degree Celsius from 1952- 2015.[17] The Indian Ocean had the fastest rate of warming among the tropical oceans, with it being one-fourth of the total ocean heat increase globally in the last two decades. Marine heat waves in the Indian Ocean are having detrimental effects on fisheries, coral reefs, and phytoplankton.

Impact of Climate Change on Fisheries in the Indian Ocean

There is now a growing consensus that global climate change is likely to put human security at risk on various fronts. In the IOR, people’s lives would be disrupted, food supply will become scarcer, and extreme weather events will lead to migration of coastal populations.[18] The fisheries sector, crucial to the blue economy of the region, has been suffering from marine pollution, illegal and over-fishing, which resulted in already depleting resource base. With the ongoing impacts of climate change on oceans and marine life becoming clearer, it is likely to exacerbate the existing issues in the sector, which is a concern for realizing sustainable blue economy agendas. Climate change could result in oceans becoming overheated and de-oxygenated and that could negatively affect coral reef environments that are the habitats of many fish species.[19] Rising ocean temperatures already has had devastating impacts on coral reefs. For example, the global mass bleaching of 1988 predominantly affected the coral reefs of the Indian Ocean and that subsequently resulted in an average of 46 per cent decline of coral cover in the region. [20] Temperature increase in the ocean surface also allows for change in zooplankton and phytoplankton composition, thereby reducing fish production.

The shifts in potential fish catch distribution vary across the IOR. The maximum catch potential is projected to increase in East Africa as well as parts of the Arabian Sea. On the other hand, the catch potentials are projected to decrease by 30 to 50 per cent in Indonesian waters, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf.[21] In the Bay of Bengal, fish catch could reduce by a significant 50 per cent and in Indonesian waters by 20 percent by mid-century. The distribution pattern of marine species is being disrupted by climate change, although it differs from region to region. Fish and other species in the warm water areas are moving towards the poles and undergoing changes in productivity of their new habitats.[22] This would mean several local extinctions and reduced diversity in the tropical areas. When it comes to abundance ranges of fish, populations in the equatorial areas tend to decline with warming oceans, whereas populations towards the Polar Regions tend to increase. Extreme weather events will also lead to instability in marine ecosystems and freshwater resource through impacts on food web processes. Rising sea levels damage mangroves, coral reefs and other fish habitats, thus affecting yield of coastal fisheries.[23] Additional concerns relate to spread of vector-borne diseases and risks of species invasions.

The threats posed by climate change will also be reflected in the coastal communities’ lives since they reside in low-lying areas and are among the most vulnerable populations globally. With climate change induced distribution change in fish species, small-scale or traditional fishers will have limited mobility and capabilities, therefore proving it difficult for them to take adaptive measures. Changes in fish distribution and abundance, along with flooding and other extreme weather events may drive these people to migrate to other areas.[24] Such a situation would prove challenging as many fishing communities in the developing countries, which constitute most of the IOR, already have poor standards of living. Adapting to climate change related issues on fisheries in addition to existing issues of degraded resources, overfishing and illegal fishing, would be out of their capacities.

Conclusion

Blue economy presents new opportunities for countries of the IOR, the vast majority of which are developing economies. Within this context, sustainable fisheries offer a way for these countries to secure their food supplies, provide livelihood to coastal communities, and contribute to their national economy. However, climate change threatens to affect ocean biodiversity adversely thereby affecting fisheries. That will imperil the blue economy agenda of the region. Fisheries are already suffering from anthropogenic challenges including marine pollution, overfishing, and other illegal activities. Climate change further amplifies these problems and contributes to the degradation of fisheries. Fish stocks production, abundance, distribution patterns are negatively impacted owing to increasing ocean temperatures, changes in the ocean chemistry with acidification, and decreasing oxygen levels. The habitats on which fish species depended on such as coral reefs and phytoplankton are facing severe threats. The socio-economic impacts on fishing communities, particularly in developing states in the Indian Ocean are far-reaching. Ocean-based economic development is at its early stages among countries of IOR, and therefore can include adaptation methods in response to impacts of climate change into fisheries management and related blue economy policies.

References :

- Ababouch, L. and Fipi, F. “Fisheries and Aquaculture in the Context of Blue Economy.” Feeding Africa 2, no. 21-23 (2015)

- Attri, V. N. “The Blue Economy and Theory of Paradigm Shifts.” The Blue Economy Handbook of the Indian Ocean. Vishwa Nath Attri and Narnia Bohler-Muller. Africa Institute of South Africa (2018). 15-37

- Barange, M., Bahri, T., Beveridge, M. C., Cochrane, K. L., Funge-Smith, S., & Poulain, F. Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture. United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization. (2018).

- Chatterjee, A. Non-traditional maritime security threats in the Indian Ocean region. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 10(2) (2014), 77-95.

- Chellaney, B.. Indian Ocean maritime security: energy, environmental and climate challenges. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 6(2), (2010).155-168.

- Clifton, J. et al. “Marine Conservation Policy in Seychelles: Current Constraints and Prospects for Improvement.” Marine Policy 36. 823-831. (2012).

- Cochrane, K., De Young, C., Soto, D. and Bahri, T. "Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture." FAO Fisheries and aquaculture technical paper 530 (2009): 212.

- Colgan, C. S. Climate change and the Blue Economy of the Indian Ocean. The Blue Economy Handbook of the Indian Ocean Region, 349-371. (2018).

- Cordner, L. Rethinking maritime security in the Indian Ocean Region. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 6(1), 67-85. (2010).

- Doyle, T. “Blue Economy and the Indian Ocean Rim.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14-1. (2018). 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1421450 - Doyle, T., and Seal, G. "Indian Ocean futures: New partnerships, new alliances and academic diplomacy." Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 11, no. 1 (2015): 2-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2015.1019994

- FAO. “State of the World’s Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016.” (2016).

- FAO. “State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation.”(2022). https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en

- Kapil Narula. “Blue Economy and Sustainable Development Goals: Aligned and Mutually Reinforcing Concepts.” The Blue Economy: Concept, Constituents and Development. Dr. Vijay Sakhuja and Cdr (Dr.) Kapil Narula, (New Delhi: Pentagon Press 2017). 1-14.

- Keen R. M. et al. “Towards defining the Blue Economy: Practical lessons from Pacific Ocean governance.” Marine Policy 88. (2018). 333-341 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.002

- Kimani, E., Okemwa, G. and Kazungu, J. "Fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean: trends and governance challenges." Stimson Centre; Washington DC, 2009.

- Krishnan, R. et al. “Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region: A Report of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India.” Springer Singapore (2020).

- Llewellyn, L. E., English, S., & Barnwell, S. A roadmap to a sustainable Indian Ocean blue economy. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 12(1), 52-66. (2016).

- Michel, D. “Tempest Tossed: Meeting Environmental Challenges in the Indian Ocean.” Stimson. March 22, 2012. https://www.stimson.org/2012/tempest-tossed-meeting-environmental-challenges-indian-ocean/#:~:text=These%20growing%20stresses%20include%20habitat,and%20mounting%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions.

- Mohanty, S.K. Dash, P. Gupta, A. Gaur, P. “Prospects of Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean.” Research and Information System for Developing Countries New Delhi (2015).

- Palacios‐Abrantes, J., Frölicher, T. L., Reygondeau, G., Sumaila, U. R., Tagliabue, A., Wabnitz, C. C., & Cheung, W. W. Timing and magnitude of climate‐driven range shifts in transboundary fish stocks challenge their management. Global change biology, 28(7), 2312-2326. (2022).

- Roy, A. Blue economy in the Indian Ocean: Governance perspectives for sustainable development in the region. ORF Occasional Paper, 181. (2019).

- Sakhuja, V. “Blue Economy: An Agenda for the Indian Government.” CIMSEC Articles 19. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.cimsec.org

- Shyam, S. S., & Elizabeth James, H. Integrating climate change and Blue Economy in fisheries research and education in India. Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute. (2018).

- Techera, E. J. Supporting blue economy agenda: fisheries, food security and climate change in the Indian Ocean. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14(1), 7-27. (2018).

- United Nations. “Minimising and addressing ocean acidification, deoxygenation, and ocean warming.” Concept paper presented at the UN Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development, Lisbon, 27 June- 1 July 2022.

- UNCSD, Blue Economy Concept Paper, (2012).

- van der Geest, C. Redesigning Indian Ocean fisheries governance for 21st century sustainability. Global Policy, 8(2), 227-236. (2017).

- Vivekanandan, E. Climate change: Challenging the sustainability of marine fisheries and ecosystems. Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 1(1 & 2), 54-67. (2013).

- Voyer, M., Schofield, C., Azmi, K., Warner, R., McIlgorm, A., & Quirk, G. Maritime security and the Blue Economy: intersections and interdependencies in the Indian Ocean. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14(1), 28-48. (2018).

Endnotes :

[1]UNCSD, Blue Economy Concept Paper, (2012)\

[2]KapilNarula. “Blue Economy and Sustainable Development Goals: Aligned and Mutually Reinforcing Concepts.” The Blue Economy: Concept, Constituents and Development. Dr. Vijay Sakhuja and Cdr (Dr.) KapilNarula, (New Delhi: Pentagon Press 2017). 1-14.

[3]Keen R. M. et al. “Towards defining the Blue Economy: Practical lessons from Pacific Ocean governance.” Marine Policy 88. (2018). 333-341 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.002

[4]Techera, E. “Supporting blue economy agenda: fisheries, food security and climate change in the Indian Ocean.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14(1). (2018). 7-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2017.1420579

[5]Doyle, T., and Seal, G. "Indian Ocean futures: New partnerships, new alliances and academic diplomacy." Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 11, no. 1 (2015): 2-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2015.1019994

[6] Llewellyn, L. English, S. and Barnwell, S. “A Roadmap to a Sustainable Indian Ocean Blue Economy.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 12:1. (2016). 52-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2016.1138713

[7]Roy, A. “Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean: Governance Perspectives for Sustainable Development in the Region.” ORF Occasional Paper 181. (2019)

[8]Doyle, T. “Blue Economy and the Indian Ocean Rim.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14-1. (2018). 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1421450.

[9]Sakhuja, V. “Blue Economy: An Agenda for the Indian Government.” CIMSEC Articles 19. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.cimsec.org.

[10]Attri, V. N. “The Blue Economy and Theory of Paradigm Shifts.” The Blue Economy Handbook of the Indian Ocean. VishwaNathAttri and Narnia Bohler-Muller. Africa Institute of South Africa (2018). 15-37.

[11]FAO. “State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation.”(2022). https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en

[12]FAO. “State of the World’s Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016.” (2016).

[13]Clifton, J. et al. “Marine Conservation Policy in Seychelles: Current Constraints and Prospects for Improvement.” Marine Policy 36. 823-831. (2012).

[14]Michel, D. “Tempest Tossed: Meeting Environmental Challenges in the Indian Ocean.” Stimson. March 22, 2012. https://www.stimson.org/2012/tempest-tossed-meeting-environmental-challenges-indian-ocean/#:~:text=These%20growing%20stresses%20include%20habitat,and%20mounting%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions.

[15]Mohanty, S.K. Dash, P. Gupta, A. Gaur, P. “Prospects of Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean.” Research and Information System for Developing Countries New Delhi (2015).

[16]United Nations. “Minimising and addressing ocean acidification, de-oxygenation, and ocean warming.” Concept paper presented at the UN Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development, Lisbon, 27 June- 1 July 2022.

[17]Krishnan, R. et al. “Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region: A Report of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India.” Springer Singapore (2020).

[18]Chellaney, B. “Indian Ocean maritime security: Energy, environmental and climate challenges.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 6-2 (2010). 155-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2010.536662

[19]Techera, E. “Supporting blue economy agenda: fisheries, food security and climate change in the Indian Ocean.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 14-1 (2018). 7-27.

[20]Kimani, E., Okemwa, G. and Kazungu, J. "Fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean: trends and governance challenges." Stimson Centre; Washington DC, 2009.

[21]Michel, D. “Tempest Tossed: Meeting Environmental Challenges in the Indian Ocean.” Stimson. March 22, 2012. https://www.stimson.org/2012/tempest-tossed-meeting-environmental-challenges-indian-ocean/#:~:text=These%20growing%20stresses%20include%20habitat,and%20mounting%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions.

[22]Cochrane, K., De Young, C., Soto, D. and Bahri, T. "Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture." FAO Fisheries and aquaculture technical paper 530 (2009): 212.

[23]Cochrane, K., De Young, C., Soto, D. and Bahri, T. "Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture." FAO Fisheries and aquaculture technical paper 530 (2009): 212.

[24]Ababouch, L. and Fipi, F. “Fisheries and Aquaculture in the Context of Blue Economy.” Feeding Africa 2, no. 21-23 (2015).

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://indiaclimatedialogue.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Temperature-Anamoly-ICD.jpg

Post new comment