Mikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and the last president of the Soviet Union, passed away in Moscow on 30 August 2022 at the age of 91. He was no ordinary leader. He was the principal architect of the end of the cold war who, through his liberal reformist policy of perestroika, unwittingly presided over the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The forces of change, unleashed by perestroika, became uncontrollable. Gorbachev wanted to make the socialist system, of which he had been an inseparable part, more ‘democratic’ and humane’. No one had predicted that the USSR would be gone in a jiffy once the cold war ended. But, with the benefit of hindsight, one can say that a system which had become brittle and hollow had to go one day. Gorbachev got the blame.

On taking over as the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985 after the death of Chernenko, Gorbachev lost no time in unfolding his reformist agenda. The January 1987 plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CC, CPSU) gave a comprehensive definition of perestroika, its urgency and its scope. The central elements of perestroika included bringing more openness (glasnost) in society, state and party apparatus, making economy more productive and competitive, and rejecting centralized command and control method of management. More elements were added with time.

Gorbachev justified the task of ‘renewal’ of socialism in terms of the urgency to correct ‘distortions’ that had crept in it under Stalin, and overcoming ‘stagnation’ that had afflicted it under Brezhnev. Perestroika, he said, was the way to make socialism more people centric, ‘democratic’ and ‘humane’. At the 19th Party Conference (June 1988), the party put forward the concept of ‘renewal of socialism’. The new concept of socialism, which until then not well defined, sought to incorporate the concepts of multiparty system, market economy and private property etc. and dilute the leading role of the party. Gorbachev’s socialism renewal plan would shake the very foundations of Marxism-Leninism on which the communist party and Soviet state were founded.

The roots of perestroika, glasnost and ‘new political thinking’ lay in the enormous problems that had accumulated in the socialist system of governance. It is not that party leaders were not aware of these. From time to time there had been discussions at the highest party fora on these issues. Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism and Stalinist purges at the 20th Party Congress (1956) comes to mind. Khrushchev denounced personality cult and initiated many reforms, but the supremacy of the party was not challenged. During the Brezhnev period lasting two decades, reformist impulses were discouraged. The economy began to stagnate. The standards of living in the Soviet Union fell behind those in capitalist countries. The intractable nationalities questions, always bubbling under the surface, were kept in control through coercion and manipulation.

The debates within the party on the concept of socialism, the need for reform etc. were mostly opaque and unintelligible to outside observers. It was difficult to be sure what was going on within the party circles. It was in the realm of external engagement that Gorbachev signalled revolutionary shift. He conceptualized ‘new political thinking’ which brought in several unprecedented changes in foreign policy. In his report to the 27th party Congress (1986) Gorbachev analyzed the world situation in traditional Marxist framework of contradictions between socialism and imperialism as also US militarism. But where he broke fresh ground was in discarding the notion of class struggle in international relations. He identified new contradictions– like the impending ecological disaster and the threat of global annihilation posed by the weapons of mass destruction. He downgraded the importance of world communist movement and solidarity with third world and placedemphasis on accommodation with the West. He talked about deideologisation of international relations, need for defensive militarydoctrines, ‘reasonable sufficiency’, a ‘common European home’, a security architecture from Urals to Atlantic etc. He described the framework of historic struggle between socialism and capitalism as outdated and unsuitable for modern times. The most significant change came in Sovietapproach to relations with the US. He soughtcooperation and not confrontation with the US. He wanted the US to revise its perception of treating the USSR as ‘evil empire’.He shook up the very ideological foundation of the socialist USSR’s foreign policy.

Surprised by Gorbachev’s reformist zeal, the West lapped up the unexpected opportunity and began to applaud and encourage Gorbachev to go on the reformist path. It sensed weakness in the adversary as it began to set the terms of engagement while stepping up its demands. It demanded the unification of Germany, freeing East European countries from the Soviet grip, dissolution of the Warsaw Treaty organisation without dissolving NATO, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, reduction of the Soviet conventional forces in East Europe, and a limitation on the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Gorbachev began to engage with the West on multiple fronts.

To prove his sincerity and credentials, Gorbachev was prepared to offer significant concessions to the West. What was surprising was he did not insist on firm reciprocal commitments and guarantees from the West. This incredible lapse on his parthas come to haunt Russia even today and is at the root of the ongoing warwith Ukraine.

Gorbachev met US presidentReagan in Reykjavik in October 1986 in which both sides explored the possibilities of nuclear arms reduction and arms control agreement. The meeting catapulted him to the status of a world leader and a statesman. In 1987, the two sides concluded the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty limiting the deployment of a class of nuclear missiles in Europe. Gorbachev made significant unilateral concessions in the area of arms control, human rights, regional conflicts etc. He pulled out Soviet troops from Afghanistan and Mongolia and also agreed on phased pullout of Soviet military from the Eastern European countries. He hoped that the West would respond with sincerity and not take advantage. That is where he went horribly wrong.

As the Belin Wall came down, Germany unified and Eastern European countries began to free themselves from the shackles the Soviet Union, a triumphant West tightened the noose and went for the kill. Socialism had been comprehensively defeated by capitalism. With the triumph of Western liberal idea, ‘end of history’ was announced by Western academics. The Soviet Union was seen as a defeated power. At best it could be a junior partner of the Westin the post-cold war order.

By the end of the eighties the USSR was facing serious internal upheavals. Glasnost had opened up a Pandora’s box of unresolved questions. The Republics were restive. Nationalities question (Nagorno Karabakh} had raised its head. The economy was in shambles. There were serious differences within the party on reforms. The 1990 Party Congress proved to be a disaster. There was no clarity within the party on where the reforms were going and what was the future of the party itself. The USSR watched helplessly as the US fought a one-sided technological war against Iraq, a Soviet ally. Nothing seemed to be going right for Gorbachev. He had lost control over the developments. He was ousted in and internal party coup in August 1991, a few months before the Soviet Union itself died. In a spectacular ‘parade of sovereignties’, one-by-one, all the republics declared independence and some of them, minus the Baltic republics, agreed to form a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). On 26th December 1991, the Soviet Union became history. In the Russian eyes Gorbachev had been discredited. But in the eyes of those who won their freedom, he was a hero. The West had a lot to thank Gorbachev for the unexpected outcome of the cold war.

Russians to this day mourn the demise of the superpower USSR but they have no love lost for socialism. The end of cold war did ended USSR but reinforced Western hegemony further. Putin once described the demise of the USSR as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”. He has been for the past 20-plus years engaged in a struggle with the Western hegemony. The Russia-Ukraine war is the outcome of the unresolved questions left over from the demise of the USSR.

It is still a mystery how Gorbachev came to trust the West so much disregarding the fact that the USSR had been locked in an existential struggle with it since the October Revolution. Ending the cold war which was bankrupting the USSR, and having a working relationship with the West was understandable. But how was it that Gorbachev did not see what was clear to the rest of the world – the reinforcement of US hegemony and the coming of the unipolar moment?

Gorbachev was an idealist. In his speeches he would often refer to Buddha, Gandhi and the ideas of nonviolence and other universal values. He had good relations with Rajiv Gandhi and visited India twice. He had strong views of Asian security architecture. This was one idea on which India would disagree. Gorbachev began the process of normalization of relations with China, an arch foe, and visited Beijing at the height of Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. India supported Gorbachev’s reforms but also was concerned about the impact on Indo-Soviet relations as Soviet economy began to falter and defence supply chains in USSR were disrupted. The demise of the USSR had a profound impact on India. India had to rethink its economic and foreign policies as USSR collapsed and anarchy gripped the Eurasian region.

Gorbachev went into a quiet, 30-year long retirement after USSR’s demise. He also set up a foundation and undertook several lecture tours. He genuinely believed that the historic confrontation between the capitalism and socialism had to end. He never regretted his decisions. Writing in 2019 in for Russia in Global Affairs he defended perestroika and hinted that the politburo was unanimous that fundamental change was needed. Describing perestroika as a ‘humanist’ project, he wrote,

“…perestroika was a wide-ranging humanist project. It was a break with the past, with the centuries when the state—autocratic and then totalitarian—dominated over the human being. It was a breakthrough into the future. This is what makes perestroika relevant today; any other choice can only lead our country down a dead-end road.”

He also admitted that the leaders had a vision but not a clear roadmap to an alternative system. In his 2019 article, he acknowledged,

“It was clear to us that identifying the path forward would be a tough challenge, and we never claimed that we had some kind of ‘train schedule’ or ‘game plan.’ That, however, does not mean we lacked a clear goal or a vision of where we wanted to go.”

No one mourned the death of the socialism although many have some nostalgia for the USSR when Russia was the superpower. Yeltsin, who had played a bold role in rescuing Gorbachev from the coup leaders, inherited the mantle of independent Russian state as its first president. Freed from the shackles of socialism, he adopted a democratic, multiparty constitution for Russia and embraced market economy. Opting for a ‘shock therapy’ for the Russian economy, he desperately sought Western technology, investments and a market economy status for Russia. However, he soon realised that the West would not treat Russia as an equal partner. When Putin took over the reins of Russia from Yeltsin in 1999, Russian economy had collapsed and the proud Russian people were reduced to penury. Putin who regarded the demise of the USSR as a ‘geopolitical blunder’ sought to restore Russian pride and glory but not the socialist system.

China had been watching the progress of perestroika with great interest and leaning appropriate lessons. Realising the need to correct the mistakes of the Mao period, Deng Xioping had begun fundamental reform process in 1979. But the trajectories of the two reforms were entirely different. Deng opened up the economy but did not loosen the control of the party. Making the right choices, he cleverly exploited the West to help China’s rise. He set hard terms like the recognition of one-China policy. Gorbachev, on the other hand, acted naively. He did not negotiate equal terms with the West as cold war entered its last lap.

Gorbachev’s legacy lies in ending the cold war, burying socialism in Russia but also freeing his successors who adopted democracy and market economy principles. He had a philosophical streak in him as he believed in higher humanist values. He correctly diagnosed that the Soviet Empire had become rotten irreparably. Socialism and the classical Marxism-Leninism based on the notions of class struggle, repression and centralised system of functioning were not the answer for the problems of the Russian society. But he did notwork out a credible alternative. He lost the geopolitical game to the West.

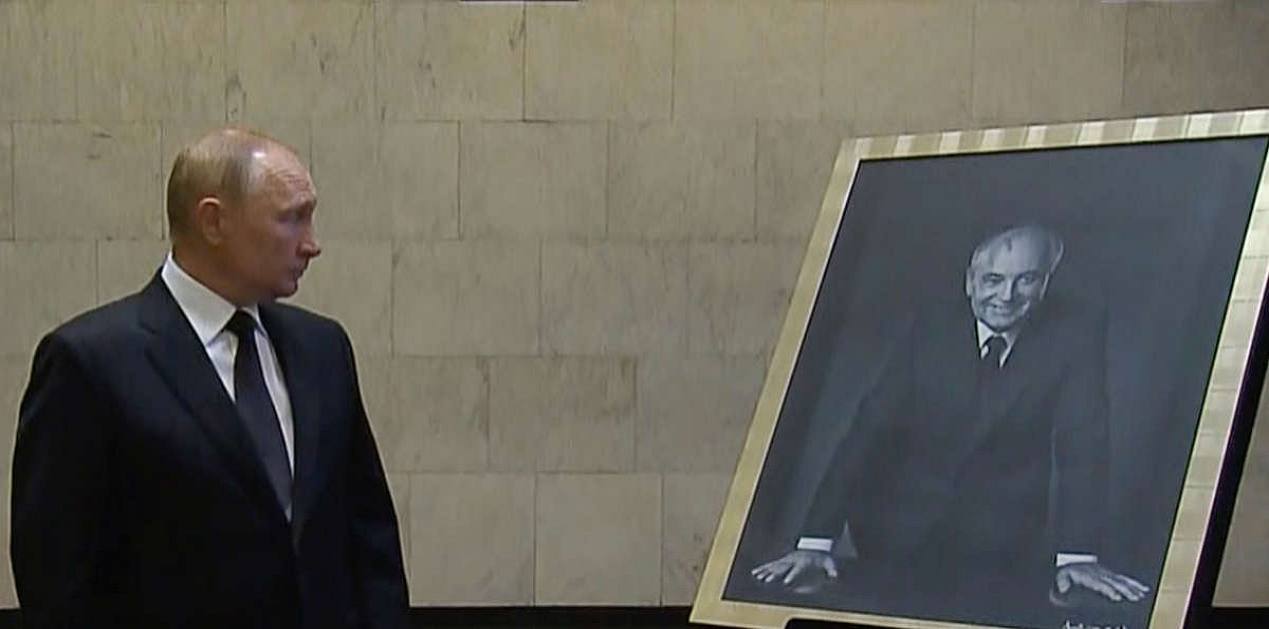

Many Russians disliked Gorbachev for the disintegration of USSR but mostly they treated him with indifference. Gorbachev was given a semi-state funeral but Putin kept away from it. Instead, he visited the hospital ahead of the funeral where Gorbachev’s body was kept. Putin paid a matter-of-fact tribute. “He led the country during difficult and dramatic changes, amid large-scale foreign policy, economic and society challenges…He deeply realized that reforms were necessary and tried to offer his solutions for the acute problems”, Putin said. It is to the credit of his successors that Gorbachev was allowed to lead a respectable, quiet life after retirement and was not humiliatedpublicly. He was buried in Novodevichy cemetery where past Soviet leaders are buried.

Russia is presently engaged in a long-drawn military conflict with Ukraine which in 1991 had triggered the end of the USSR with declaration of independence. Gorbachev had recently criticised Russia’s war with Ukraine. If Gorbachev had a Ukraine problem then, Putin has it now. The outcome of the ongoing war will define Russia of the future. No can say which way history will turn in the new cold war.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://img-s-msn-com.akamaized.net/tenant/amp/entityid/AA11ms7V.img?h=630&w=1200&m=6&q=60&o=t&l=f&f=jpg&x=813&y=250

Post new comment