Introduction. Since the early 90s, experts have been saying that the next war will be fought in cyberspace. A ‘cyber Pearl Harbour’ would meltdown government systems, cripple critical infrastructure and plunge modern militaries and societies into darkness. Modern warfare is highly dependent on technology, and it has not happened in Ukraine. This is a conventional war where bullets rather than bytes are raining down on combatants and civilians, causing devastation and misery.

Specialists in cyber warfare predicted that Russia would strengthen its conventional onslaught with a devastating cyberattack. Ukrainian forces would be blinded, critical infrastructure wrecked and Russian disinformation rampant. As the military experts were surprised by Russia’s stalled invasion, so have the cyber specialists by the lack of major digital attacks.

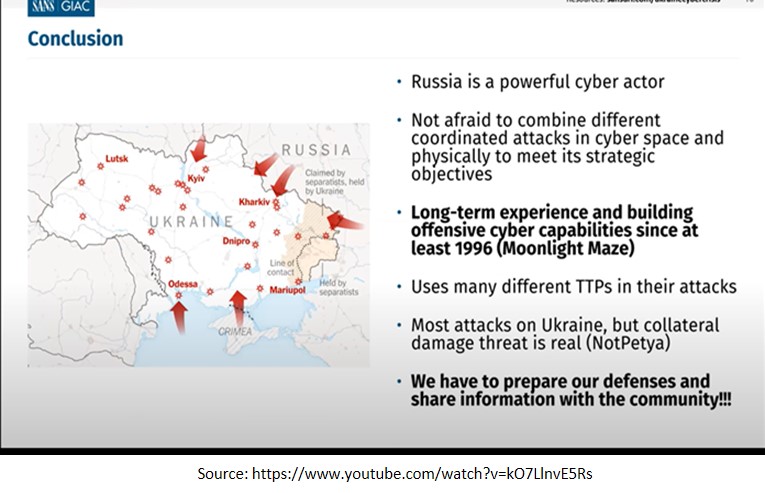

There seems to have been little effort to strike at the core of Ukraine’s internet infrastructure. Cyber operations could have played a significant role in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia has sophisticated cyber capabilities, and its hackers have worked their way into Ukrainian networks for many years. The Russian government has not used cyber operations as an integral part of its military campaign yet to facilitate the advance of ground or air forces. The reasons for this underuse of Russia’s sophisticated cyber capabilities so far in the conflict are unclear.

It is almost impossible to know the reason for the apparent restraint. We do not understand why the Russians have held back, whether cyber operations have been attempted and failed, or Russia has held its cyber capabilities in reserve for using them later.

There are several theories. Maybe Ukrainian cyber security has improved with Western help, perhaps the widespread skirmishing of cyber ‘partisans’ from both sides has got in the way. It could be that the Russians are keeping Ukrainian networks operating for their own purposes to assist their intelligence gathering. It is unlikely that everything the Russians may be doing has been made public.

IISS Report on Cyber Capabilities and National Power

The recent International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Report on Cyber Capabilities and National Power has interesting observations on Russia. These are: [1]

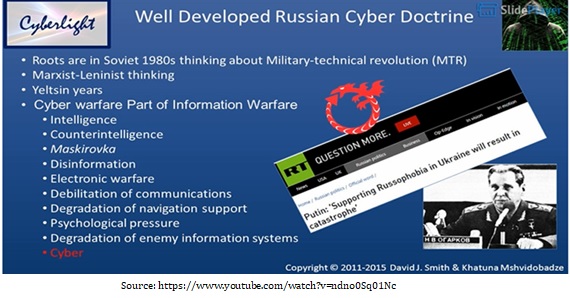

Strategy and Doctrine. Its conflict with the West dictates Russia’s cyber strategy, and it sees cyber operations as a crucial component of a more comprehensive information war. Russia’s Information Security Doctrine of December 2016[2] covered strategic deterrence, the information security of government agencies, critical national infrastructure and citizens, the armed forces and countering the threats posed by rival states, terrorists and criminals. A military commentary declared that dominance in cyberspace and military power are prerequisites for victory in modern war.[3]

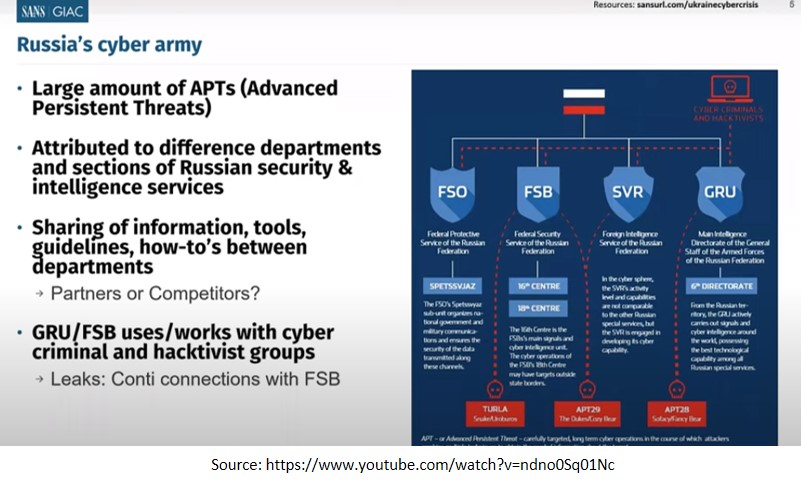

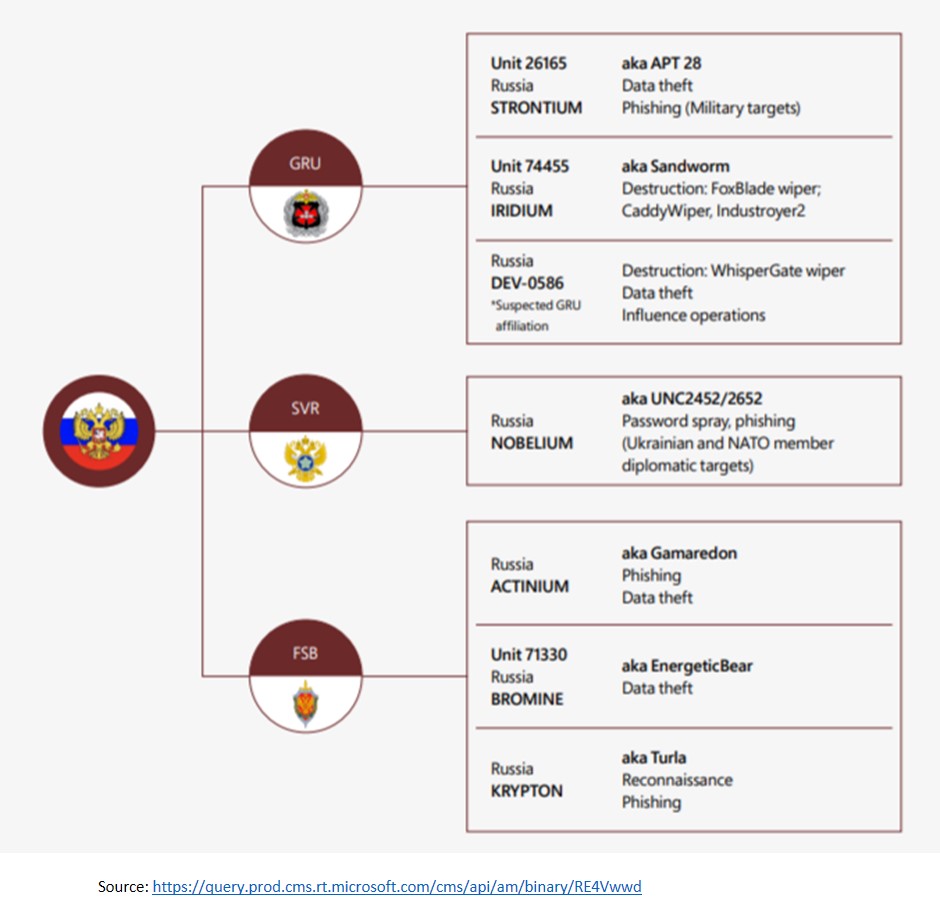

Governance, Command and Control. Russia’s cyber governance is hierarchical and centralised under the president’s personal control. For offensive cyber operations, the primary responsibility is with the Main Directorate of the General Staff (formerly the GRU). Russia’s main domestic intelligence agency, the FSB, is responsible for cyber defence against attacks on government systems and national critical infrastructure.

Core Cyber-Intelligence Capability. Russia has widespread regional and global cyber intelligence capabilities. Russian intelligence operations occasionally come out less sophisticated than those employed by Western cyber operators. The alleged misuse of social media is a vital national security issue. The use of organised cyber-crime expertise and patriotic hackers has substantially enhanced Russia’s cyber capabilities.[4]

Cyber Empowerment and Dependence. Russia is greatly dependent on foreign ICT corporations and has a less impressive digital economy than the U.K or France. It seeks to redress critical weaknesses in its cyber security through government regulation and the creation of a sovereign internet, known as the ‘sovereign RuNet’ and by encouraging the development of an indigenous digital industry. In December 2019, Russia claimed to have successfully tested the disconnection of the RuNet from the internet. The tests involved government agencies and telecoms companies, including local ISPs.

Cyber Security and Resilience. The updated Information Security Doctrine includes the key element of the RuNet and the surveillance regime of the operational investigative measures system (SORM).

Global Leadership in Cyberspace Affairs. With some successes, Russia has led diplomatic efforts for two decades to curtail what it sees as the dominance of cyberspace by the West, and particularly the U.S. In cyber diplomacy, primarily through multilateral forums, Russia cooperates closely with China.

Offensive Cyber Capability. Russia has credible offensive cyber capabilities and has used them extensively as part of a broader strategy to disrupt the policies and politics of perceived adversaries, especially the U.S. Likely, each of the three main Russian intelligence agencies (the FSB, GU/GRU and SVR) have offensive cyber capabilities. It has run extensive cyber-intelligence operations, some of which reveal increasing levels of technical sophistication. However, Russia appears not to have prioritised developing the top-end surgical cyber capabilities needed for high-intensity warfare. Most of the detected attacks are relatively unsophisticated compared to the methods designed by the U.S. and several of its allies for high-intensity warfare and/or strategic surgical effect.

The Security Service of Ukraine neutralised, in 2020, 103 Russian cyberattacks against websites of Ukrainian public authorities. The purpose was to infiltrate information systems to modify or destroy data or delegitimize the Ukrainian authorities by spreading disinformation.

Russia’s Demonstrated Cyber Warfare Capabilities

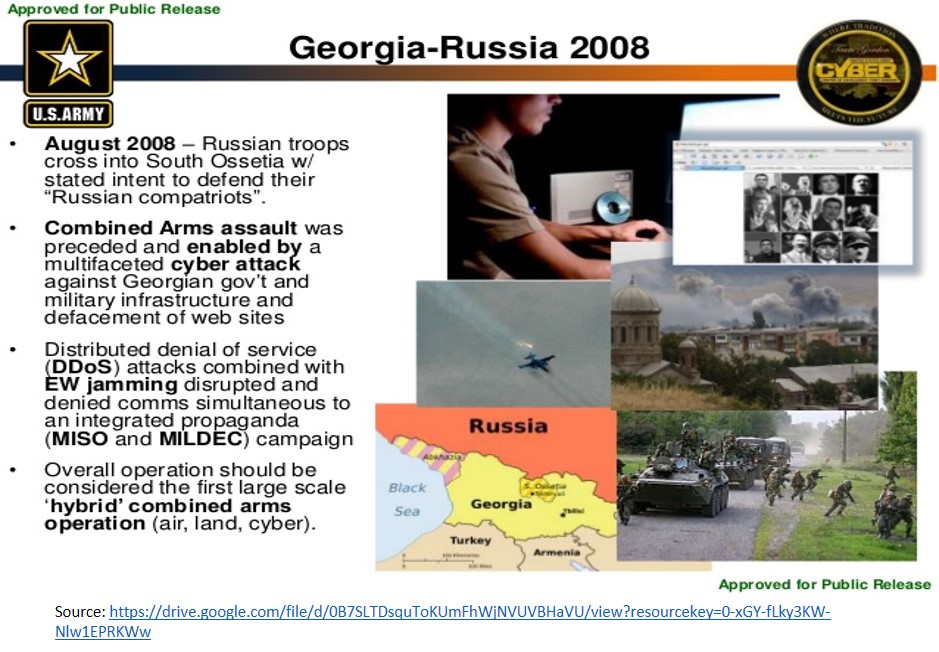

Russia has demonstrated its cyber warfare capabilities many times. It is the first country to carry out cyber operations in conjunction with kinetic actions against an adversary country.

Estonia Apr – May 2007. From 27 April onwards, Estonia was hit by major cyber-attacks, The websites of the Prime Minister, the Parliament and almost all of the country’s government ministries were targeted by the attack. Online services of Estonian banks, telecommunications operators and three of the country’s six big media outlets bodies were taken down. However, there was no tangible evidence that the Russian government carried out these attacks.

Georgia 2008. In the August of 2008, the war between Russia and Georgia was remarkable for its addition of large-scale, overt cyberspace attacks that were well synchronised with conventional military operations. This is the first time in the history of a co-ordinated cyberspace domain attack synchronised with significant combat actions in the other warfighting domains of ground, air and sea.[5]

Ukraine Crimea 2014. In Ukraine, Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea included cyber operations simultaneously with kinetic ones. Distributed denial of service attacks strategically flooded Ukrainian networks to crash operations

Two Attacks on Power Grid. Just before Christmas of 2015, in coordination with its annexation of Crimea, Russian hackers sabotaged the western Ukrainian power grid by using a Trojan virus, Black Energy, which resulted in almost 2,30,000 households losing power. Though the outage continued only a few hours, the operating systems of the three regional power-distribution companies affected remained compromised long after the lights were back on.

Nearly a year later, another cyber-attack recognised as Industroyer crippled power for about one-fifth of Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, for about an hour[6]. The U.S. and E.U. named and blamed Russian military hackers for the attacks.

Russia can use cyber operations to disrupt enemy communications, organisation and logistics, leading many to assume that it would use such tactics in this war[7]

Hacking of Apps Used for Artillery Fire Support. To speedup the process of calling in artillery fire support Ukrainian artillery units were using apps in their smart phones. Russian hackers hacked the app easily, geo-locate artillery batteries accurately and brought down devastating counter battery fire to destroy the guns.[8]

NotPetya (2017). In June 2017, the GRU, the Russian military intelligence service, launched one of its periodic cyber operations of destructive malware(NotPetya) against a range of Ukrainian targets of computers in Ukraine’s banks, electricity companies, newspapers, a nuclear facility, health ministry, the national railway and its postal service rendering the infected computers completely unusable. It took a long time to clean up and rebuild the relevant IT systems.

Russia’s use of an uncontrolled, self-propagating worm combined with a global IT vulnerability meant it lost control of the operation, as the infection spread worldwide, extensively damaging systems in 60 other countries, including the U.S. [9] It caused an estimated US$10 billion in damages globally.

Russia is a cyber-superpower capable of disruptive and potentially destructive cyber-attacks with a serious arsenal of cyber weapons and hackers. Russia hosts the world's largest concentration of cyber criminals. In 2021, approximately three-fourths of ransomware's exponentially rising revenue went to cyber criminal groups in Russia. It exposed a soft underbelly of cyber vulnerability across the West[10].

Pre Invasion Cyber War

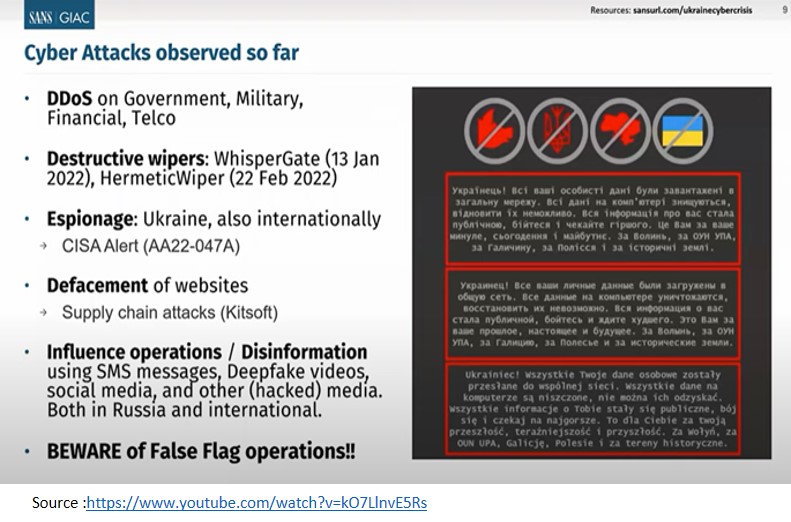

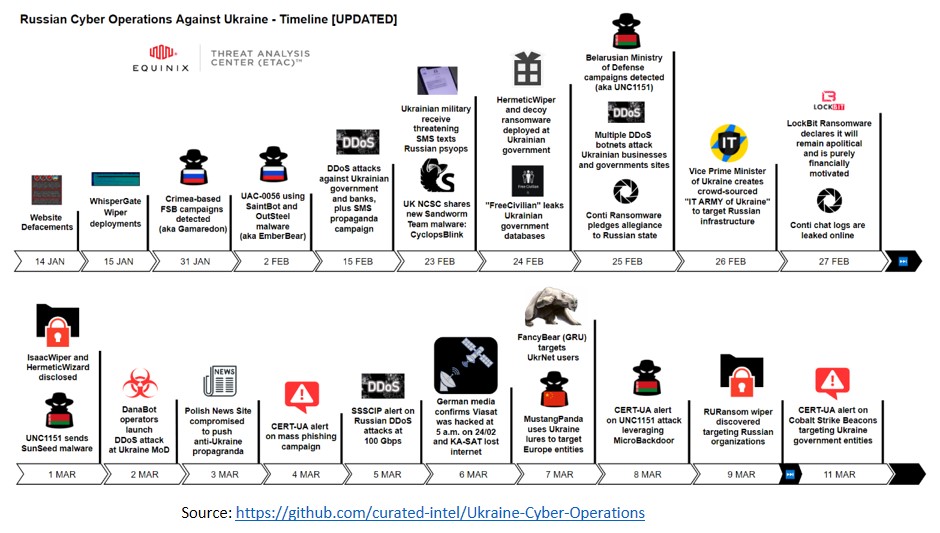

Before Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, it was expected that cyber warfare would play an essential role in the conflict. Before the invasion began, Ukraine had been under a continuous barrage of cyberattacks. Since February 15, 2022, Ukraine experienced more than three thousand DDoS attacks till February 24. In January 2022 itself, wiper malware, a malicious software that erases the targeted computer’s hard drive was detected in Ukrainian government networks and the private sector. There were a number of espionage attacks on high-value targets. New malware were distributed through phishing campaigns.

Text messages were sent to personnel of Ukraine’s 53rd and 54th Mechanized Brigades near the frontline, informing the soldiers that Russian units deployed to Donbas would attack on February 22. The messages called on Ukrainian servicemen to desert their posts to save their lives in a psychological warfare tactic. On February 23, Ukrainian government websites of Cabinet of Ministers, Federal Security Service of Ukraine, Defence Ministry, Parliament, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were hit with relatively unsophisticated and short-lived distributed-denial-of-service attacks. In the early phase of the conflict, some ATMs in Ukraine were unable to dispense cash.

On the morning of the invasion, most crucially, hackers jammed the satellite signal of Viasat, which delivered broadband satellite Internet services to Ukraine and some other parts of Europe. Viasat provides Internet service to the Ukrainian army and several Western militaries. It is suspected that the cyber attack on Viasat was carried out to compromise Ukraine’s command-and-control systems. The attack was marginally successful.

Ongoing Cyber War

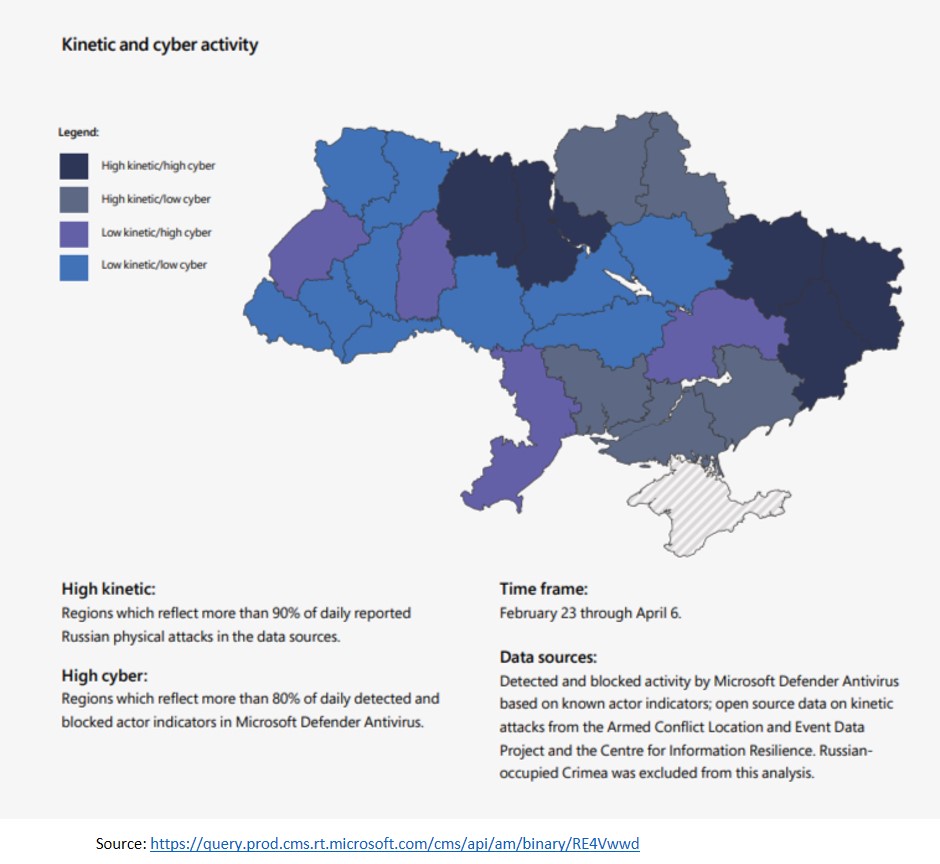

Since then, the cyber war is continuing between Russia and Ukraine. Russian hackers are active to support of Russian military’s strategic and tactical objectives. There are numerous examples of cyber operations and military operations working in tandem against a common target set. Sometimes cyber attacks closely preceded a military attack. [11]

Kinetic and cyber military operations have been directed toward similar military targets. High intensity military actions frequently overlapped with concentrated cyber operations during the first two months of the invasion. Kinetic and cyber activity map is given below.

The timeline of Russian Cyber Operations against Ukraine is given below.

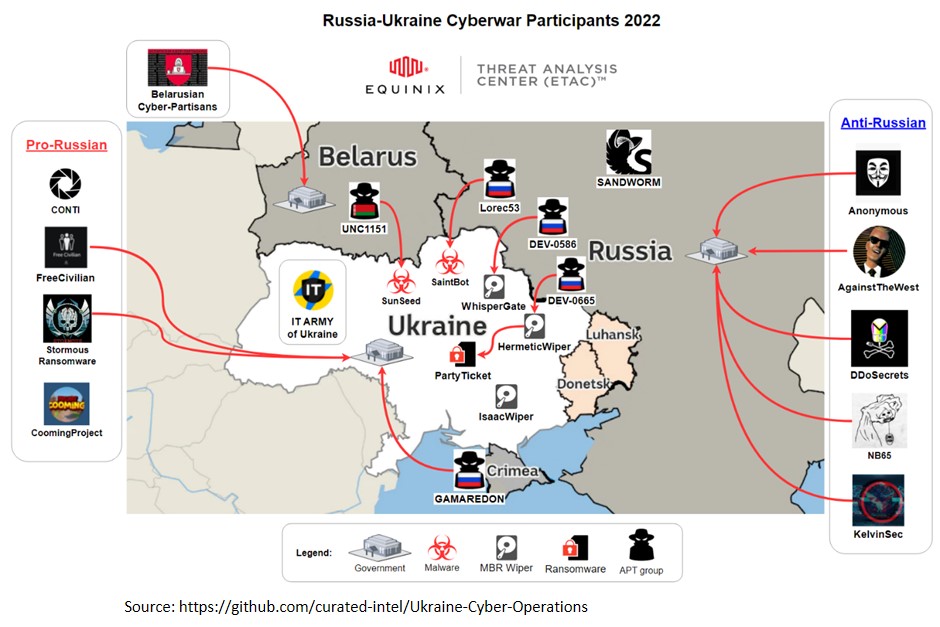

The various players are:

Russian Hackers

Russia has effectively carried out offensive cyber operations, including cyber espionage, information and disinformation operations and disruptive cyberattacks against Ukraine. It has not got the requisite media traction. Perpetrators include UNC2452, Turla, APT28, UNC530, UNC1151, UNC806, and other actors closely linked to intelligence services in Russia, Belarus, and other countries.

Russia may be cautious in its approach as some of the best cyber weapons lose effectiveness after their first use because they exploit previously unknown vulnerabilities that can be quickly patched.

Michael Rogers, former NSA director, warned against underestimating Russian cyber weapons. He said, “Expect cyber activity designed to not just deny access but really ultimately destroy or degrade infrastructure to take away Ukrainian military capability, to forestall the Ukrainian government and Ukrainian military’s ability to coordinate forces. In other words, to increase the probability of Russian success. The Russians could cause extensive damage in the United States, and should we choose, we could cause extensive damage within Russia.”

Russian ransomware operators offered their services to the government, threatening to retaliate against governments that sought to punish Russia. These seem to be loosely controlled proxy groups and not a unified effort. A Ukrainian member of the Russian‐ linked Conti ransomware group, for instance, leaked the group’s internal chat logs to counter the pro-Russian effort[12].

Russia has deployed additional destructive malware from its arsenal of cyber weapons every week. Kharkiv and Kyiv, cities under siege from Russian shelling, have experienced cyber-enabled disruptions to Internet services. At the beginning of the invasion in Ukraine, three strains of the Wiper malware simultaneously attacked local infrastructure. The virus deleted information and data from drives connected to the infection source. The strains of the Wiper malware were:

- HermeticWiper. It was detected on February 23, 2022, one day before the start of the invasion. Along with HermeticWiper some other malware was deployed, including a worm that was used to spread the wiper. The wiper proliferated beyond the borders of Ukraine and may have affected some systems in Baltic countries.

- WhisperGate. ThisWiper malware was put on Ukrainian systems on January 13, 2022. The wiper was planned to look like ransomware and presented victims with a way to decrypt their data for a fee. Actually, the malware deleted the system. The wiper was found on systems all over Ukraine, including the Foreign Ministry and networks used by the Ukrainian cabinet.

- IsaacWiper. On February 24, 2022, Russia launched IsaacWiper against Ukrainian government systems, coinciding with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The attacks took place just after the HermeticWiper attacks and appeared more targeted than the HermeticWiper attacks.

- CaddyWiper. On March 14, 2022, security researchers identified a new wiper targeting Ukrainian systems. The wiper does not share significant code similarities with other malware analysed by the researchers. The wiper was designed to inflict damage while still preserving access to the affected network.

- RURansom Wiper. On March 1, 2022, RURansom wiper was detected. It represents one of the first uses of a wiper by pro-Ukrainian hacktivists, and provided a new dimension in the ongoing cyber conflict. RURansom functions as a wiper and offers victims no opportunity to pay to have their systems decrypted. The malware appears to check the victim’s systems for a Russian IP address, and if it doesn’t find one, the malware halts execution. The malware creators seem to be releasing new versions of the wiper, which may only grow more potent over time.

- Double Zero. Ukraine CERT-UA released an alert about the new wiper variant, DoubleZero, used to target Ukrainian entities. First observed on March 17, 2022, when threat actors used phishing attacks to deliver the malware, which overwrites content and deletes Windows registries before shutting down the infected system.

The details of some of the threat actors active in this cyber conflict are given below.

UNC1151. Belarusian threat actor UNC1151 is suspected to be conducting cyberattack targeting over 70 government websites. UNC1151 is accused of the following:

- Defacing the websites, and posting threatening messages before Russian troops crossed the border into Ukraine.

- Installing a publicly available backdoor, MicroBackdoor, onto Ukrainian government systems.

- Launching a phishing campaign against the Ukrainian and Polish governments and militaries

- Hacking the email accounts of Ukrainian military personnel in a mass phishing attack

- Phishing campaign using compromised Ukrainian military emails to target European government personnel aiding Ukrainian refugees with SunSeed malware.

APT28. The Russian threat actor APT28 has carried out a credential phishing campaign targeting users of the popular Ukrainian media company UKRNet. The campaign was suspended after it was detected by Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG).

Gamaredon. On March 20, 2022, Russian APT Gamaredon was found spreading the LoadEdge backdoor among Ukrainian organisations. The backdoor allows Gamaredon to install surveillance software and other malware onto infected systems for facilitating a cyber-espionage campaign targeting Ukraine.

DanaBot. In the first week of March, Russian groups were found using DanaBot, a malware-as-a-service platform, to launch DDoS attacks against Ukrainian defence ministry websites.

Conti RaaS Group. The Conti RaaS group announced, on February 25, 2022, that it was supporting Russia and the Russian people and has warned that any western nation conducting cyber warfare operations against Russian assets will suffer massive takedowns of critical infrastructure. The group is connected to more than 400 cyber attacks all over the world, approximately 300 of which were against U.S.-based organisations.

The Sandworm Team. attributed to Russia’s General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) has been attributed to reintroducing the NotPetyawormable malware strain, and leveraging the Cyclops Blink Linux botnet, to target internet-of-things (IoT) devices to execute distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

Strontium. Microsoft reported an interesting event. It stated that it had been tracking Strontium, a Russian GRU-connected actor for years. Strontium was attacking Ukrainian entities. Microsoft stated:

We recently observed from Strontium, a Russian GRU-connected actor we have tracked for years. This week, we were able to disrupt some of Strontium’s attacks on targets in Ukraine. Microsoft obtained a court order on April 6, 2022 authorizing it to take control of seven internet domains Strontium was using to conduct these attacks.

Strontium was also targeting government institutions and think tanks in the U.S. and the E.U involved in foreign policy. Ukraine’s government was informed.

Before the Russian invasion, Microsoft began working to help organisations in Ukraine, defend against an onslaught of cyberwarfare that has continued relentlessly since the invasion began[13].

Cisco and other U.S. companies are also working with Ukraine to kill large numbers of remote access Trojans that are used to gain remote control of computer systems.

Google is now helping protect 150 websites in Ukraine from cyber attacks.

Russia’s Cyber Defence

Though offensive cyber capabilities of Russia are well known, its defensive capabilities are not very clear. In the current conflict questions are being asked about Russia’s cyber defence. Presently the Russians appear to be spending a lot of time defending their own networks. It may be taking resources away from a cyber offensive. Today it is Russia that is complaining of being the target of cyber offensives.

On March 2, 2022, Russia’s cyber defence agency gave an alert that 17,500 IP addresses and 174 internet domains were involved in DDoS attacks on Russian sites and provided private organizations with mitigation measures.

The website of the Russian Foreign Ministry, in a statement on March 29, 2022, said, “In fact, state institutions, the media, critical infrastructure facilities and life support systems are subjected to powerful blows everyday with the use of advanced information and communication technologies. At the instigation of the Kiev regime, an ‘international call ‘of anti-Russian computer specialists has been announced, in fact, forming ‘offensive cyber forces’. The bill for “malicious attacks against us goes to hundreds of thousands per day.”

The statement talked of Russia’s capacity to resist these attacks. It warned that “No one should have any doubts: the cyber aggression unleashed against Russia will lead to serious consequences for its instigators and executors. The sources of attacks will be established, the attackers will inevitably be held responsible for what they have done in accordance with the requirements of the law.”

Conclusion

The Economistheadline “Cyberattacks on Ukraine Are Conspicuous by Their Absence” may be misleading. Cyberwar is playing out in the shadows, happening now and will most probably escalate.

Generally the most destructive cyberoperations are covert and deniable by design. In the heat of war, it’s harder to keep track of who is conducting what attack on whom, especially when it is advantageous to both victim and perpetrator to keep the details concealed.

Experts believe that Russia has far greater cyber capabilities than it has displayed so far. However, it is not that cyber operations did not take place along with the invasion. An analysis of the Russian cyber-operations reveals that there has been proactive and persistent use of cyberattacks to support Russian military objectives. The absence of overpowering “shock and awe” effect in cyberspace has led to the flawed deduction that Russia’s cyber-units are incapable.[14]

General Paul Nakasone, the Commander of United States Cyber Command and the Director of the National Security Agency, said on April 5, 2022, that Russia’s military and intelligence forces are employing a range of cyber capabilities, including espionage, influence and attack units, to support its physical attacks and its international propaganda campaign. The current crisis is not over.

A complete understanding of the cyber aspect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is probably not possible until after the conflict ends.

Endnotes :

[1]Cyber Capabilities and National Power: A Net Assessment, IISS, June 28, 2021 available at: https://www.iiss.org/blogs/research-paper/2021/06/cyber-capabilities-national-power

[2]Presidential Administration, ‘DoktrinainformatsionnoibezopasnostiRossiiskoiFederatsii’, December 6, 2016 available at: https://rg.ru/2016/12/06/doktrina-infobezobasnost-site-dok.html.

[3] Ministry of Defence, ‘Prevoskhodstvo v kiberprostranstvestanovitsyaodnimizusloviypobedy v voynakh’, 22 April2019 available at: https://function.mil.ru/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12227079@egNews.

[4]Cory Bennett, ‘Kremlin’s ties to Russian cyber gangs sow US concerns’, Hill, 11 October 2015, available at: http://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/256573-kremlins-ties-russian-cyber-gangs-sowus-concerns.

[5]David Hollis, Cyberwar Case Study: Georgia 2008, Small Wars Journal, January 6, 2011 available at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/journal/docs-temp/639-hollis.pdf

[6]Jason Blessing, Where is Russia's cyber blitzkrieg? TheHill, March 09, 2022 available at: https://thehill.com/opinion/cybersecurity/597272-where-is-russias-cyber-blitzkrieg?utm_source=&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=47920

[7] Nadiya Kostyuk and Erik Gartzke, Cyberattacks have yet to play a significant role, April 4, 2022 available at: https://www.yahoo.com/now/cyberattacks-yet-play-significant-role-123157558.html

[8]Adam Meyers, Danger Close: Fancy Bear Tracking of Ukrainian Field Artillery Units, CrowdStrike, December 2016,

[9]Maggie Miller, US concerns grow over potential Russian cyber targeting of Ukraine amid troop buildup, The Hill, December 16, 2021 available at: https://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/586033-us-concerns-grow-over-potential-russian-cyber-targeting-of-ukraine-amid

[10]Jack Detsch and Mary Yang, Russia Prepares Destructive Cyberattacks, Foreign Policy, March 30, 2022 available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/30/russia-cyber-attacks-us-ukraine-biden/

[11]Special Report: Ukraine, An overview of Russia’s cyberattack activity in Ukraine, Digital Security Unit, Microsoft, April 27, 2022 available at: https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RE4Vwwd

[12]Brandon Valeriano et al. Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine Didn’t Rely on Cyberwarfare. Here’s Why, Cato Institute, March 7, 2022 available at: https://www.cato.org/commentary/putins-invasion-ukraine-didnt-rely-cyberwarfare-heres-why

[13]Tom Burt, Disrupting cyberattacks targeting Ukraine, Microsoft, April 7, 2022 available at: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2022/04/07/cyberattacks-ukraine-strontium-russia/

[14]Shane Snider, Steven Burke, FBI Cybersecurity Strike Against Russian Botnet Is ‘Awesome Moment’ For MSPs, April 07, 2022 available at: https://www.crn.com/news/security/fbi-cybersecurity-strike-against-russian-botnet-is-awesome-moment-for-msps

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://thumbor.forbes.com/thumbor/711x474/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/62470d09c556475f8e2b15fa/Cyber-Attack-A02/960x0.jpg?fit=scale

Post new comment