Introduction

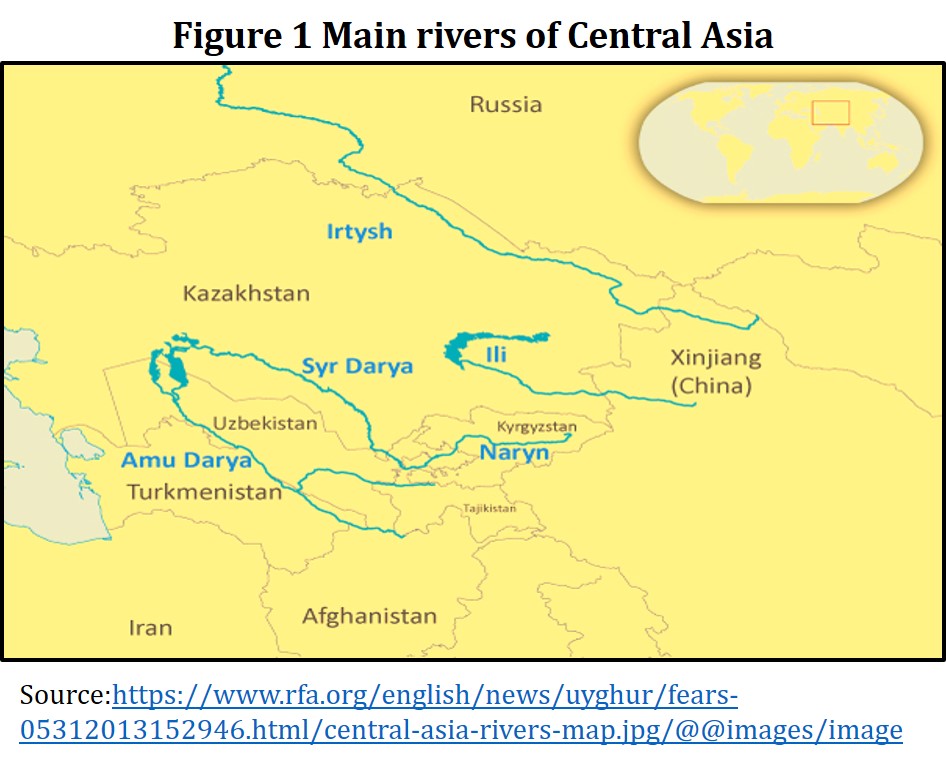

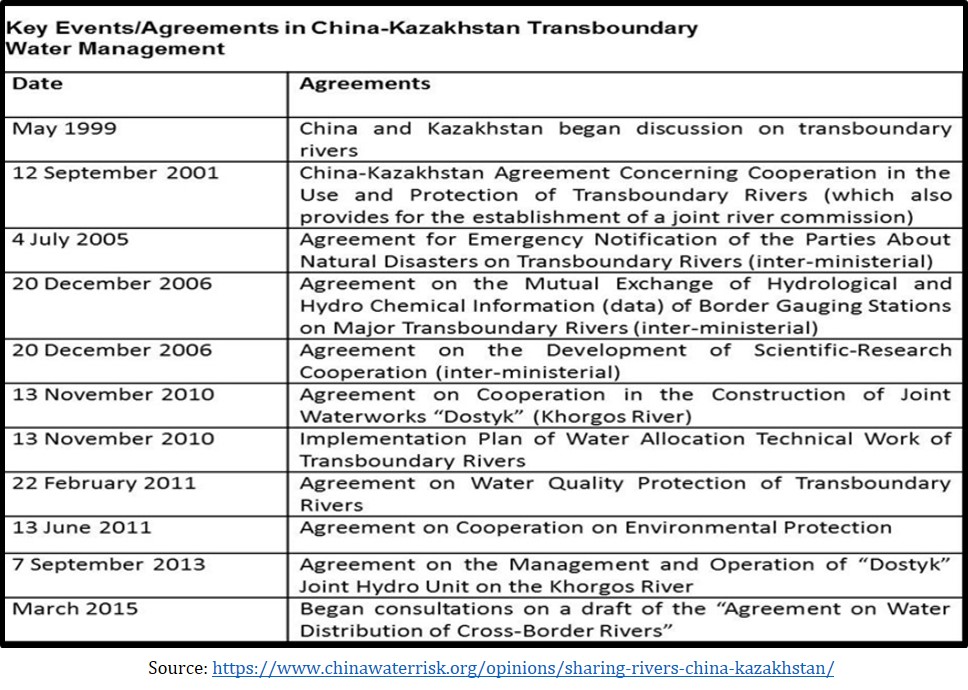

There are 24 trans-boundary rivers between China and Kazakhstan, and all of their mainstreams flow to form a clear upstream-downstream relationship. In this water-scarcity zone, the trans-boundary flow of water is limited. Therefore, negotiating water use and allocation becomes a formidable task that regularly runs into impediments. Nevertheless, the realities of water scarcity, river basin ecological conservation, and rising development in Sino-Kazakh trans-boundary river basins have led to water allocation cooperation. Although both parties have reached a general framework agreement on the “principle of equity and rationality” in the use and protection of all 24 trans-boundary rivers, there are still operational challenges in both countries’ management of trans-boundary water resources that must be overcome in order to achieve the goal of equitable distribution of interstate water resources.[1]

Sino-Kazakh Contestation over Ili and Irtysh River

China is seen as a hydro-hegemon that frequently directs decisions on the distribution of water resources from the trans-boundary rivers like the Ili and Irtysh. China’s hydro-hegemony is founded on elements such as its geographical position and economic prospects that enable the financing and building of advanced hydro infrastructure. China has over-exploited waters of the interstate river systems to the detriment of lower riparians. Beijing holds the status of hydro-hegemon in one of the key water-scarce regions of the globe, where there is potential for future water-related conflict since the bulk of Asia’s freshwater comes from rivers beginning in China.[2]

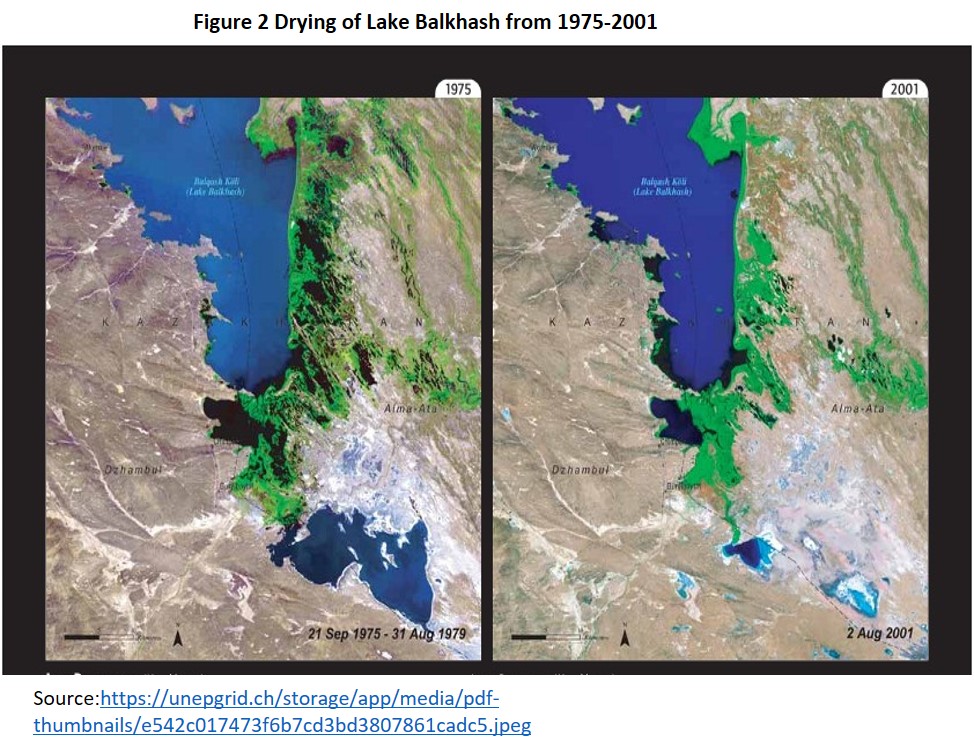

In the context of climate change and a widespread shortage of fresh water, two of Kazakhstan’s key rivers, the Irtysh and Ili river basins, are being harmed by the uncoordinated actions of neighbouring nations such as China, where these rivers originate. The Ili River serves as the primary water source for Balkhash Lake in Kazakhstan, which is currently suffering from Chinese mismanagement of the Ili River’s water supply. Concerns have been raised about the lake being shallow due to microclimate desertification and water extraction for increased hydraulic and industrial production.[3] As visible in the figure below, the southern part of the lake has lost about 150 sq kilometers of water surface area.[4] Environmental scientists warn that if this trend continues, the Balkhash will follow in the footsteps of the Aral Sea, which has dried up.[5]

The Irtysh River, which originates in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, is the most important of the 24 trans-boundary rivers that run across China and Kazakhstan. The Irtysh River has been exposed to an asymmetrical water distribution arrangement between Beijing and Kazakhstan. The poor management of the trans-boundary Rivers by various water usage models and methods, on which there is no consensus and pertinent agreements, is one of the causes of the changes in the Irtysh River system. Approximately half of Kazakhstan’s surface water originates from the territory of neighbouring states. Therefore, this challenge is particularly significant for Kazakhstan, which has limited water resources and a rising scarcity of pure drinking water.

Kazakhstan’s limited water supply also results from the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) strategy of unilaterally increasing the water intake from the trans-boundary Rivers. The PRC uses most of the water from these rivers to expand the hydropower potential of its northwestern region of Xinjiang, which borders three nations in Central Asia and has been the target of Chinese oppressive ethnic minority policies towards Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz minority communities. The geostrategic significance of Xinjiang for China’s Belt and Rod initiative (BRI) is also well known. China has asserted that Xinjiang’s economic growth could support regional stability. Beijing also uses it to justify large-scale water consumption from Trans-Boundary Rivers shared with Kazakhstan. Chinese water intake projects in the basins of these two rivers are thought to be the primary cause of reduced flow, which has a detrimental impact on the industry, agriculture, and the environment in a large section of Kazakhstan.

Population and production capacity in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s border areas are significantly greater than in the border provinces of Kazakhstan. On the Ili River in China, over 40 reservoirs and 250 water intake facilities have been constructed, in addition to more than 500000 hectares of land being irrigated. As a result, the Ili River’s flow has also fallen from 17.8 to 12.7 km3 per year during the last 20 years.[6]

Beijing is implementing the second phase of China’s Great Western Development Strategy in Xinjiang, which is scheduled to be finished by 2030. It will necessitate an increase in water withdrawal from trans-boundary river systems. Ecologists say that increased water withdrawal is already harming the environment. One such instance is how the removal of water from the Black Irtysh River (Some writers, particularly in Russia and Kazakhstan, refer to the upper course of the Irtysh river, from its source to entering Lake Zaysan, as the Black Irtysh) has resulted in a reduction in the water flow into Lake Zaysan and a reduction in the water level of this lake. Reduced river flow may also result in drier climates in some regions of Kazakhstan, a decrease in soil moisture, reduced agricultural yields, deterioration of pastures, and desertification of most of Kazakhstan’s north-eastern region.

Concerning the problem of the rational use of water resources, China insists on the priority rights to water withdrawal from these rivers. Beijing does not recognize the concept of equal water-sharing along the border regions. Completing a large portion of the projects proposed for Xinjiang development will significantly affect Kazakhstan’s future water usage balance. It will also lower the hydrological and chemical characteristics of water courses affecting the biodiversity of these river basins.

Negotiations

An examination of materials on China’s water politics reveals that Beijing opposes the concept of a collective water usage agreement or collective administration of shared water resources. For example, by refusing to ratify the 1997 UN Convention on the ‘Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses’, Beijing declared that upstream countries had absolute authority over water from trans-boundary rivers located on their territory, as well as the right to use as much water as they needed regardless of the consequences for downstream countries.[7] Kazakhstan, although being a lower riparian, has not signed or ratified this UN treaty.

Several scholars have emphasised the strategic relevance of political and economic cooperation and the mediation of water-related legislation for the growth of cordial and mutually beneficial ties between China and Kazakhstan. However, despite close political and economic ties with Kazakhstan, Beijing arbitrarily uses water from the Ili and Irtysh Rivers without considering its ramifications for Kazakhstan. There are several channels of contact between the two states that might help reach a census on this issue. For example, high-ranking officials from both countries attended the ninth meeting of the China-Kazakhstan Cooperation Committee in November 2021. In September 2021, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with his Kazakh colleague Mukhtar Tileuberdi in Dushanbe and claimed that the relationship between China and Kazakhstan had been elevated during their fight against theCOVID-19 pandemic. Beijing has frequently exalted its strong bilateral relations with Kazakhstan. However, the water-related issues have not been mentioned by either side.[8]

Kazakhstan’s Initiatives to Mitigate Water Issues

Kazakh Government requested financial assistance from the Global Environment Facility (GEF), an independent financial organization that unites more than 180 nations and offers grants for projects related to environmental issues. The GEF has allocated 12 million USD to improve the ecological situation in Central Asia, extending to Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan as well as Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Kazakhstan received 2 million USD of the total sum to aid in revitalizing the area around Balkhash.[9]

The Kazakh government has been adequately addressing water scarcity issues by shifting agricultural development from extensive to intensive methods of agriculture. International specialists claim that Kazakhstan is altering how it manages its water resources by focussing particularly on the connections between extensive water usages in various economic sectors. This is done with the help of international organisations and donor funding. A fresh focus is being placed on increasing water efficiency. By 2030, Kazakhstan will reduce its reliance on imported water by 4.5 billion cubic meters per year. Another motive for Kazakhstan to adjust its water policy was to lessen future tensions with China.

Kazakhstan has long highlighted the trans-boundary Rivers as shared property, yet it also considers China’s desire to utilise its water resources. However, Nur Sultan has always advocated that water distribution be done while considering Kazakhstan and other countries located downstream of the trans-boundary Rivers. In order to reach an equitable agreement on water sharing, Kazakhstan consequently depends on reasonable negotiations. Nonetheless, China has avoided the negotiating process to finish its key hydraulic projects in Xinjiang to assure large-scale water withdrawal from trans-boundary Rivers. Sensible use of interstate water resources is critical for the survival of tens of millions of people, regional political stability and prosperity, and hence the establishment of cordial ties and trust between China and Kazakhstan.

Conclusion

Kazakh policymakers are fully conscious of the significance of water as a downstream nation with tough terrain and significant agriculture industry. Nur-Sultan is also aware of how crucial it is to continue having fruitful dialogues with its neighbours about water challenges. China has the right to develop its land for the benefit of its people. Still, because Kazakhstan is a downstream country with an agricultural-based population, Beijing also has obligations to consider Nur Sultan’s water needs. Water politics will play a significant role in how Kazakhstan and China’s ties develop in the future. Continued communication between the two countries is also necessary to tackle water problems and safeguard Lake Balkhash.

Endnotes

[1]Chenjun Zheng (2021): Sino-Kazakhstan transboundary water allocation cooperation study: analysis of willingness and policy implementation, Water International. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02508060.2021.1871718

[2]Fatima T Kukeyeva, et al., “Is Ili/Irtysh Rivers: A 'Casualty' of Kazakhstan-China Relations”, Research Article, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 2018 Vol: 17 Issue: 3.https://www.abacademies.org/articles/is-iliirtysh-rivers-a-casualty-of-kazakhstanchina-relations-7304.html

[3]Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, “Water Politics Will Drive Kazakhstan’s Relations With China”, land portal, January 13, 2022. https://landportal.org/es/blog-post/2022/04/water-politics-will-drive-kazakhstan%E2%80%99s-relations-china

[4] “The Shores of Lake Balkhash”, the geopolitical futures, April 12, 2019. https://geopoliticalfutures.com//pdfs/the-shores-of-lake-balkhash-geopoliticalfutures-com.pdf

[5]Shamseer Mambra, “Aral Sea Disaster: Why One of the Biggest Inland Seas Dried Up? Marine Insight, February 16, 2021.https://www.marineinsight.com/environment/aral-sea-disaster-why-one-of-the-biggest-inland-seas-dried-up/

[6]Kunduz Adylbekova, “How does Kazakhstan solve the problem of drinking water shortage in the era of oil leadership in Central Asia? Cabar Central Asia, August 27, 2019. https://cabar.asia/en/how-does-kazakhstan-solve-the-problem-of-drinking-water-shortage-in-the-era-of-oil-leadership-in-central-asia

[7]Fatima T Kukeyeva, et al., “Is Ili/Irtysh Rivers: A 'Casualty' of Kazakhstan-China Relations”, Research Article, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 2018 Vol: 17 Issue: 3.https://www.abacademies.org/articles/is-iliirtysh-rivers-a-casualty-of-kazakhstanchina-relations-7304.html

[8]Wang Yi Meets with Kazakh Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Mukhtar Tileuberdi, Ministry of Foreign affairs of Republic of China, September 16, 2021. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202109/t20210917_9714374.html

[9]Aybulat Musaev, “Kazakhstan Gets $2M To Save Major Lake From Depletion”, Caspian News, January 26, 2018.https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/kazakhstan-gets-2m-to-save-major-lake-from-depletion-2018-1-25-34/

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://media.springernature.com/lw685/springer-static/image/chp%3A10.1007%2F698_2018_307/MediaObjects/451388_1_En_307_Fig1_HTML.png

Post new comment