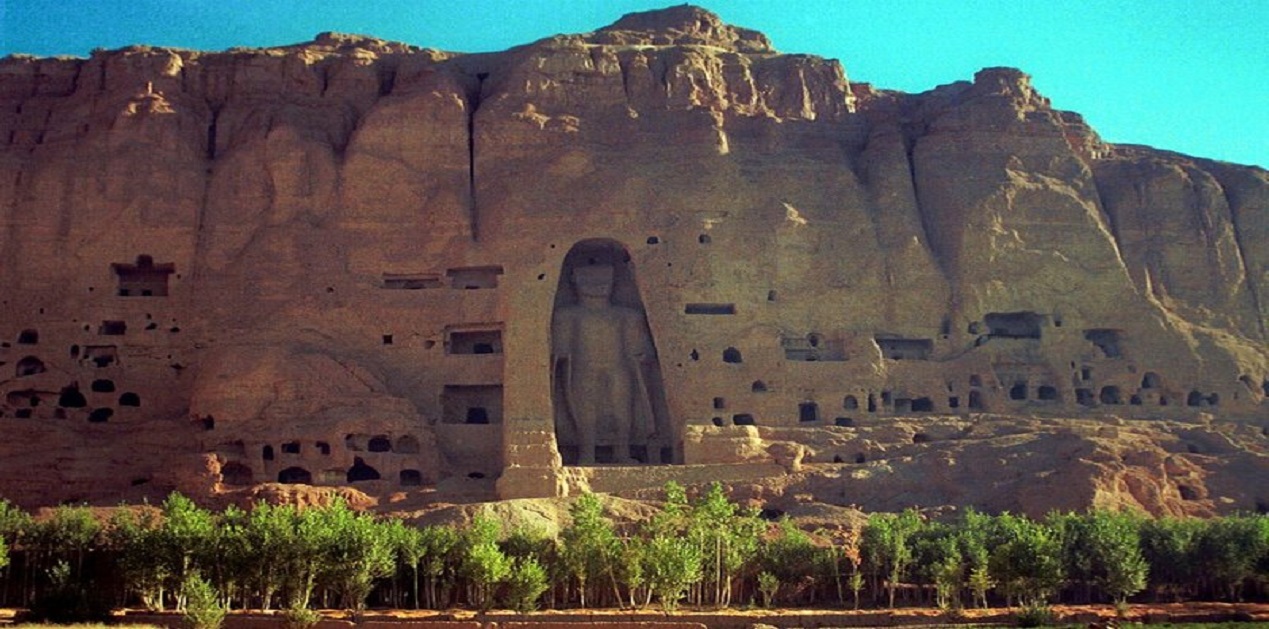

In Afghanistan, Buddhist cave temples are concentrated in three regions: Jalalabad (180 caves), Haibak (200 caves) and Bamiyan (1000 caves).[1] The Bamiyan Buddhas are part of a Buddhist site in Bamiyan Valley of Bamiyan River, 230km northwest of Kabul and 2500m above sea level, it separates the Hindu Kush from the Koh-i-Baba Mountains, [2] and is part of the present-day Afghanistan. Human behaviour and its influence on the material culture has been in the discussions a lot, but this influence also works other way around. Objects are not just passive entities in the society but play an active role and participate in the interactions taking place between humans and object itself. Objects influence the way people shape themselves within the society and this influence has far reaching consequences.[3] When the term “object agency” is being used in the article it essentially refers to what the object or the monument in this case represents in the society over a period of time. This will be further discussed by using the example of the Buddhas of Bamiyan and the role these played in the society in ancient time as well as the present. The Buddhas stood for a lot of different things over a period of time. It played a specific role in the ancient times and it stands for something else entirely in the present. This stems from how the society interacts with an object over the course of time and how these interactions shift over time due cultural exchanges and exchange of ideas. This article explores the different shifts faced by the site of Bamiyan Buddhas and how these shifts affected their representation in the society.

Historical Background

Bamiyan valley was considered to be an important site as it was very conveniently situated, the region played an integral role in the Silk Routes trade and connected the Indian subcontinent to one of the most significant trade networks. Buddhism spread to the Bamiyan valley, first during the Mauryan period under Asoka’s rule (3rd century BCE) and later under the Kushan Empire (1st to 3rd century CE). [4] Several attempts were made to date the site as well as the construction of the Buddhas and it was later deduced that the Eastern Buddha (544-595CE) was built earlier than the western Buddha (591-644CE) through carbon dating.[5] The formation of the monastery is said to be dated back to 2nd century BCE, quite earlier than the construction of the Buddhas. Other than the statues the monastery has about 700 caves for housing travellers, pilgrim hostels and storage. The dating of the whole site is still contested and not much is known about the Buddhist period of the site. The monastery was active in 630 CE, the evidence for that can be found in the texts written by Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang), the Chinese monk who travelled all along the Buddhist sites in the Indian subcontinent. [6] The Buddhist period was first disrupted in 770CE and the region became Islamic for a short period of time. The second Buddhist phase started in 870 CE and the region was finally dominated by Islam in 977 CE. [7]

The region played an important role in trade connectivity as it functioned as a sanctuary for the traders travelling long distances with goods.[8] Such monasteries allowed the traders to avoid the politics of such regions and also provided a safe place for them to exchange these traded goods. A lot of Buddhist sites played this particular role such as Taxila, Mes Ayanak and Kakrak Valley. In the ancient time the Buddhas were not just monuments but also worked as huge signs for the travellers indicating a place of sanctuary for them. The Buddhas were visible from a great distance and allowed the travellers to follow the path to the monastery where they could rest and then move forward with their journey. As far as object agency goes the Bamiyan Buddhas are one of the best examples to demonstrate the influence of objects on people. The towering Buddhas were hard to miss and the travellers from different regions following different religions would associate the Buddhas with a safe haven. The region witnessed not only the exchange of goods through traders but also exchange of culture and ideas and played a significant role to demonstrate tolerance.

Destruction of the Site

In March 2001 the Buddhas were blown to pieces by the Taliban to take down the ‘gods of infidels’[9]. Where the once towering Buddhas used to stand, now there is just a gaping cavity in the space. This act of destruction led to a huge public outcry because of the severity of their actions against such important cultural monuments which played such a crucial role in the ancient times and were a part of the world’s cultural heritage in the present times, the act was declared as cultural terrorism. Even Genghis Khan left the Buddhas standing when he destroyed the valley in the 13th century.[10] The Bamiyan Buddhas were designated as World Heritage site in 2003 by the United Nations. The site was also put under the endangered sites list as there was a significant boom in tourism after the destruction of the Buddhas. This leads to the question as to why the sites were only declared as world heritage after it witnessed such destruction. Its historical value was paramount even before the destruction of the Buddhas. The site got real recognition from the western world only after such destruction, which even led to an increase in tourism. There were a lot of talks of rebuilding the sculptures to their former glory but this was put on hold due to the instability of the surrounding area of the sculpture. A lot of damage had taken place due to the previous destruction and the priority was shifted to stabilising the surrounding structure.[11]

Such sites witness a lot of looting and material remains start showing up on the black market. After the Bamiyan Buddhas incident it did not take long before remains from the sites were being sold in Pakistan as paper weights.[12] Such markets, especially the ones funded by the west reveal that there is a demand for such items. These artifacts are given a monetary value, which in turn supersedes it historical and cultural values. This also goes on to show that as long as there is a demand in the market for such artifacts the looting will continue. This goes on to show that even though the site was declared to be a World Heritage site there is still a blatant disregard for it as a cultural heritage site. While United Nations declared it to be a world Heritage site and is working on the conservation of the site it would also be helpful if it introduced strict regulations regarding the sale of the stolen artifacts from such sites.

Recent Tidings of the State of Afghanistan

On 15th August 2021, United States of America had withdrawn the last of their troops from Afghanistan which resulted in 2021 Taliban offensive that led to the fall of the republic in Kabul[13]. The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan took place rather rapidly following the departure of the troops from the United States. Though the fall of the government did not come as a shock but the time it took for Taliban to take over left the world flabbergasted. The fall of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the reinstatement of the Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan has left the future of the state in a pit of uncertainty. The state has been struggling with multiple issues under the establishment of this new government such as the economic crisis and the workers not joining the workforce[14] as well as the struggles faced by the academics of the state. The education sector has taken a big hit as the nation’s universities “officially” functioning and they are even registering the attendance but the classes are not running. [15] The fallback in the field of Research will affect a lot different arenas of the society one of which would be in understanding the cultural heritage of the nation. While these issues are dominating at the moment it is essential to question whether the cultural heritage will survive under this new rule. As mentioned above the state of Afghanistan is host to multiple Buddhist sites which are heavily influenced by the Gandhara traditions. Other than the Buddhist sites there are also sites like Ai Khanum, the Hellenistic city which could be on the verge of being wiped out from the cultural landscape of the present state of Afghanistan.

Future of Other Such Sites Under Taliban

“The Taliban not only destroyed the Buddhas at Bamiyan, but also a large number of statues throughout Afghanistan” (Manhart, 2009). This statement portrays the instable future of the cultural heritage of Afghanistan. Among such sites is the site of Mes Aynak. The site was already under threat when in May 2008 Ibrahim Adel, Minister of Mines and Shen Heting, General Manager of MCC (Chinese Metallurgical Group Corporation) signed the Mes Aynak mining contract.[16] Though the government tried to save the site with the MAAP project (Mes Aynak Archaeological Project) a lot of mismanagement between the stakeholders has led to a state of confusion regarding the site itself. The site forces one to ask one if the most crucial questions while dealing with such archaeological monuments i.e., what is more important protecting the past or development of the present and the future. Since research has come to a standstill in the nation at the moment, it doesn’t seem likely that this project will continue and the remains from the site could be salvaged. The site sits on top of copper ores which are now being mined by the Chinese corporation but it is also important to understand if the habitants of the site were aware of these resources and what role did, they play in the society in those times.

Other than the Buddhist sites there are also sites like Ai Khanum which now face these uncertainties. The site of Ai Khanum is a Hellenistic city in North-eastern Afghanistan and dates back to early 3rd century BCE. The city served military and administrative functions in antiquity, though they sustained their livelihood through agriculture, trade and mining. The excavations revealed that the construction of the buildings uncovered were a combination of Mesopotamian, Greek and Central Asian in nature. [17] This again shows the cultural diversity existing in the region in the ancient times. These are only a few examples of such sites which need to go through excavations and research to gather more knowledge regarding the region’s past. While these issues are not in the forefront right now, they are something which need to be addressed in the near future as these cultural monuments do not just belong to the Afghanistan cultural heritage but are an integral part of our shared history which connected the whole of the Mediterranean region with not just Central Asia but also the Indian Subcontinent. Taliban at the moment has not taken any actions against these sites but it has also not issued any statement regarding the preservation of these cultural heritage sites. Another question which arises with this is; Will UNESCO interfere if any actions are taken against any such site of cultural and historical importance? How will the international community work towards the safety of these sites?

Though the future of the sites remains unknown a lot can still be accomplished regarding the preservation of the site in a digital manner and while that is a possibility it would still require the approval of and assistance from the current government as the majority of the data is still in Afghanistan itself. A prompt action is needed to make sure that these sites are not damaged in the future and to avoid looting at these sites as those are the most likely consequences of this new change in the leadership of the nation’s government.

Conclusion

The site of Bamiyan Buddhas is an outstanding example of what could happen to other such sites under the new leadership in Afghanistan. The site which stood for a flourishing society and a sanctuary in the ancient times radically changed in the year 2001. Now the site stood for the actions of an extremist terrorist group and the cavity where the Buddhas used stand now expressed the extreme intolerance of the society. As discussed above, objects carry some form of agency but in this particular case the absence of an object or monument speaks volumes itself. With the current state of affairs, the cavities may go through another change and their agency could change along with it. This constant change takes place because of the interactions that occur between the society and the object over time, and as new ideas emerge and cultural exchanges take place the agency of these objects start moulding according to these changes in the society. It remains to be seen how this new development will affect the site and what changes will it bring to the agency of the cavities where the Buddhas used to stand, as it could have far-reaching consequences to the cultural landscape of the nation.

References

[1]Higuchi, Takayasu, and Gina Barnes. "Bamiyan: Buddhist cave temples in Afghanistan." World Archaeology 27.2, 282-302, 1995.

[2]Michael Petzet, the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the remains. Bässler, 2009.

[3]Chris Gosden, "What do objects want?" Journal of archaeological method and theory 12.3, 2005, 193-211.

[4]Michael Petzet, (2009). The giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the remains. Bässler.

[5]CatharinaBlänsdorf, et al. "Dating of the Buddha statues–AMS 14C dating of organic materials." Monuments and Sites 19, 231-236, 2009.

[6]Michael Petzet, the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the remains. Bässler, 2009.

[7]Michael Petzet, the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the remains. Bässler, 2009.

[8]Michael Petzet, the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the remains. Bässler, 2009.

[9]Carlotta Gal, “From Ruins of Afghan Buddhas, a History Grows”, The New York Times, December 6 2006.

[10]Carlotta Gal, “From Ruins of Afghan Buddhas, a History Grows”, The New York Times, December 6 2006.

[11]James Janowski, "Bringing Back Bamiyan's Buddhas." Journal of Applied Philosophy 28.1, 44-64, 2011

[12]James Janowski, "Bringing Back Bamiyan's Buddhas." Journal of Applied Philosophy 28.1, 44-64, 2011.

[13]Safiullah Taye, "Afghanistan’s Political Settlement Puzzle: The Impact of the Breakdown of Afghan Political Parties to an Elite Polity System (2001–2021)." Middle East Critique (2021): 1-20.

[14] “Resurgent Taliban and shaken economy upend life in Afghanistan” at asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Afghanistan-turmoil/Resurgent-Taliban-and-shaken-economy-upend-life-in-Afghanistan

[15] “Afghanistan’s academics despair months after Taliban takeover” at nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03774-y [17th December 2021]

[16]Paul Graham Newson and Young Ruth, Post-Conflict Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. Routledge, Pp. 264, 2017.

[17]Jeffrey D Lerner, "Ai Khanum." The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, 2013.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://www.npr.org/2011/07/27/137304363/bit-by-bit-afghanistan-rebuilds-buddhist-statues

Post new comment