Background

The past year began with a pathological threat for the world which was detrimental not only for public health, politics, and economics but also for global security. The keywords for the year 2020 were COVID-19, geopolitical realignment, multilateralism, demographic shift (migration), and religious movement. The year was especially marked by transnational terrorism, presenting an intricate mosaic for the policymakers.

According to the United National Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (CTCED), the impact of a pandemic on the terrorism was on the rise due to its online presence which led to increase in the reach of the groups. The Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team stated that Al-Qaida and ISIL affiliates1, Boko Haram, and the Taliban have continued to conduct large-scale attacks in several parts of the world, including Afghanistan, West and East Africa and the Lake Chad Basin.2

The pandemic has also forced many migrant workers to return to their countries of origin, thereby causing a dramatic decrease in remittances and potentially exacerbating existing grievances. COVID-19 has severely impacted the enactment of security measures, trial, reintegration, measures, and Counter Violent Extremism programming. The effects of the pandemic symbolise a worldwide generational catastrophe.

In this article, the aim is to assess the trajectory of terrorism in Islamic State and Al Qaeda and what is on the horizon for the year 2021.

Introduction

In March 2019, President of the US Donald Trump announced triumph over Islamic State (IS) after the success of joint operation with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) against the Islamic State fighters in Baghouz, Syria3, and later in October 2019 with the killing of its caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and spokesman, Abu al-Hasan al-Muhajir.4 The physical representation of Caliphate may have been defused with the assassination of Baghdadi and the assumption was that the organisation seemed to be at a nadir; however, the Islamic State was far from being defeated and in fact, 2020 was quite a decisive year for the group.

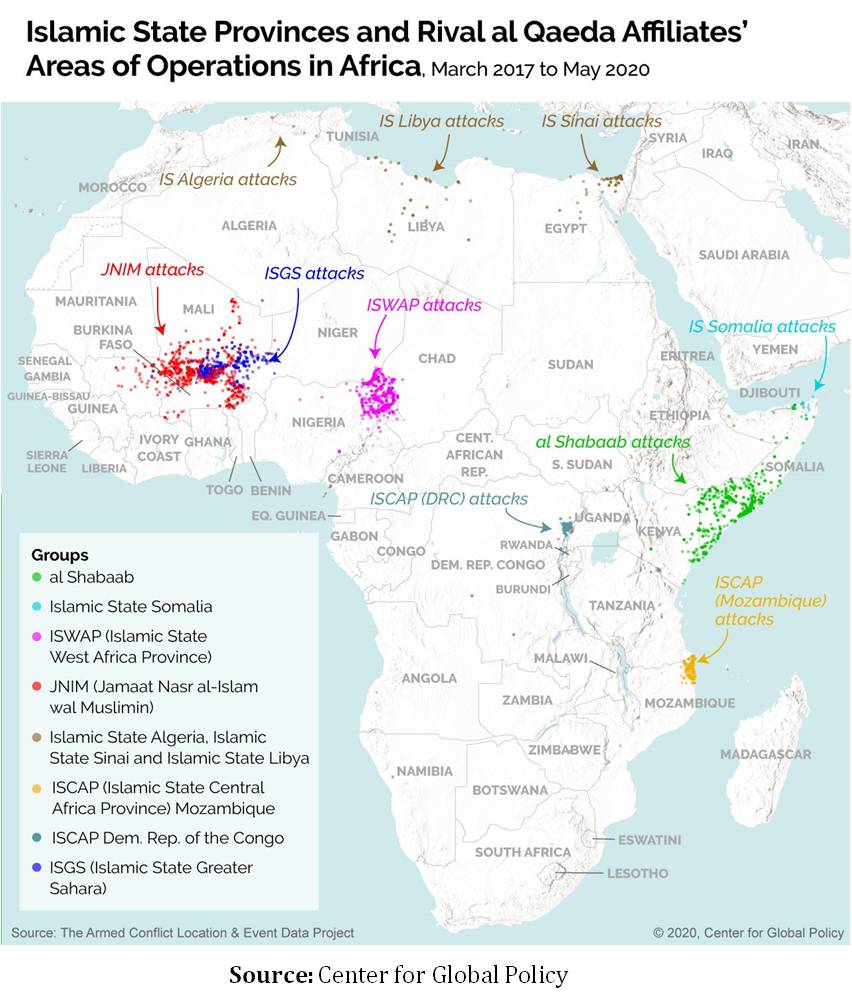

The Islamic State continued to decentralise, making its network more difficult to target. In Iraq and Syria, the group made attempts to reconstruct itself. The group has indeed bolstered its presence in Sub-Saharan Africa.5

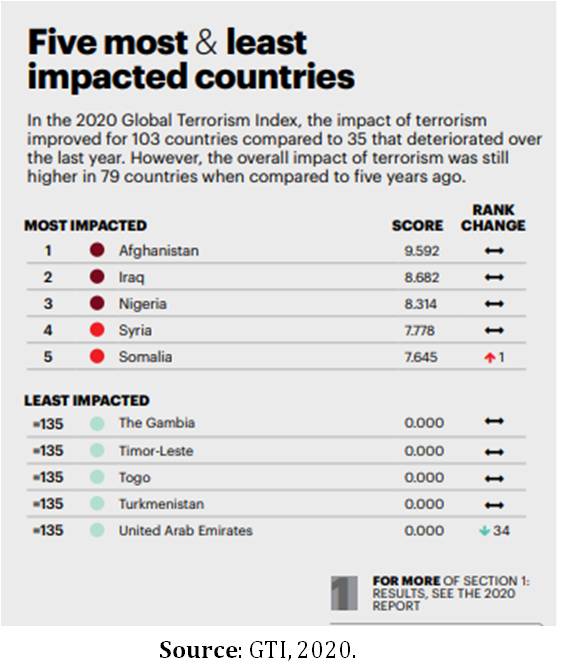

As per the Global Terrorism Index 2020, ‘As the level of terrorist activity continues to fall in the Middle East and South Asia, new terrorist threats are beginning to emerge. The most prominent of these are the spread of ISIL affiliate groups in sub-Saharan Africa.’6 Out of five most impacted countries, Nigeria and Somalia ranked third and fifth, respectively.7

Covid-19 pandemic worsened the situation by increasing the number of terror activities. While the government was busy combating and controlling the pandemic, it was ripe opportunity for the terror groups to consolidate and expand their area of influence. Both IS and Al Qaeda issued public notice through their media channels giving guidance on how to utilise the moment and launch an attack on the ‘crusaders’. The leaders of Al Qaeda suggested that non-Muslims must convert to Islam, as only this religion is immune to such a deadly pandemic. On the other hand the Islamic State encouraged its followers, sympathisers, and lone wolves to wage global jihad from wherever they were located. This phase is also known as ‘infodemic’ as a causal effect of the pandemic. In January, ISIS newsletter Al-Naba published that “a new disease spreads death and panic” in “communist China” for the torture done to the Uyghur Muslims. Furthermore, Iran suffered an outbreak, and the newsletter wallowed that the contagion was an exemplary punishment from God for Shiite Muslims “idolatry”.8

Later in early March 2020, IS Issued a Sharia Directives on the pandemic based on the al- Bukhari’s collection of Hadess on Plague9 and asked the followers of Islam to have trust in God and believe that the illness strikes only on the will of the Allah.

In their own published weekly newsletter al-Naba, Islamic State provided an overview of their operations and the casualties. The group has been actively operating in Iraq and West Africa, which covers Nigeria, Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. The group here is referred to as Islamic State West Africa Province, ISWAP.

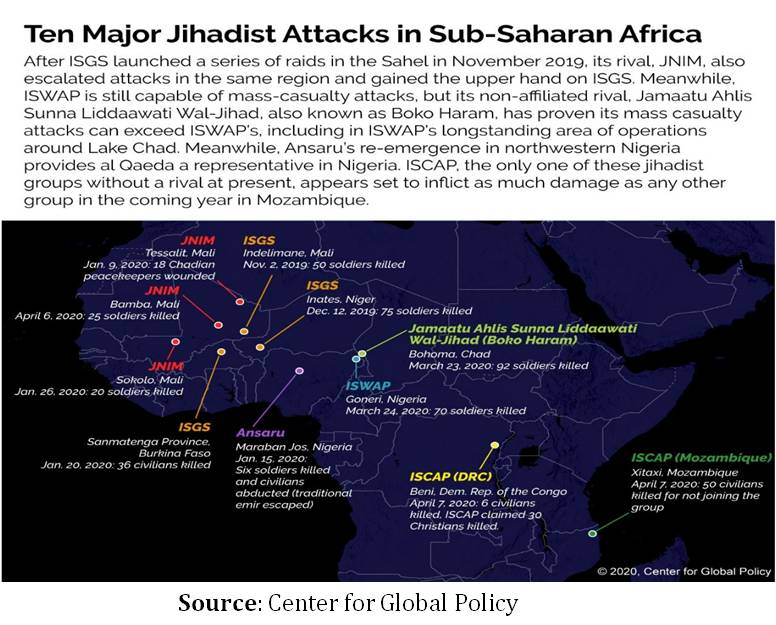

It gives authority to the argument that the Islamic State's epicentre is tilting towards Sub-Saharan Africa. One of the reasons could be the withdrawal of the United States from Africa and reducing peacekeeping troops10, as well as by other European countries like France which is planning to reduce its strength of 5100 troops this year.11 Advancements in 2020 denoted that Africa is now perhaps the most crucial region for the Islamic State at a global level. As per the Western intelligence officials IS has improved its striking capabilities and acquired better technologies, tactics and arms and ammunition. Islamic State has been using its network for resurgence in Africa. As on today the Islamic State West Africa Province is probably the strongest and most active of the ISIS affiliate. They are operating from Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Cameroon.12

Group's al-Naba newsletter also reflected that 39% of the front-page news in 2020 covered the information related to Nigeria, Sahel, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo.13

While Iraq remained the most active battleground for the Islamic State in terms of attack frequency, but the fatality per attack ratio was significantly larger in Khorasan, West Africa, and Central Africa, and lastly, the Islamic State's East Asia Province (ISEAP). Eastern Africa was characterised by many attacks and high casualties, while Central Africa recorded more than average number of attacks.14

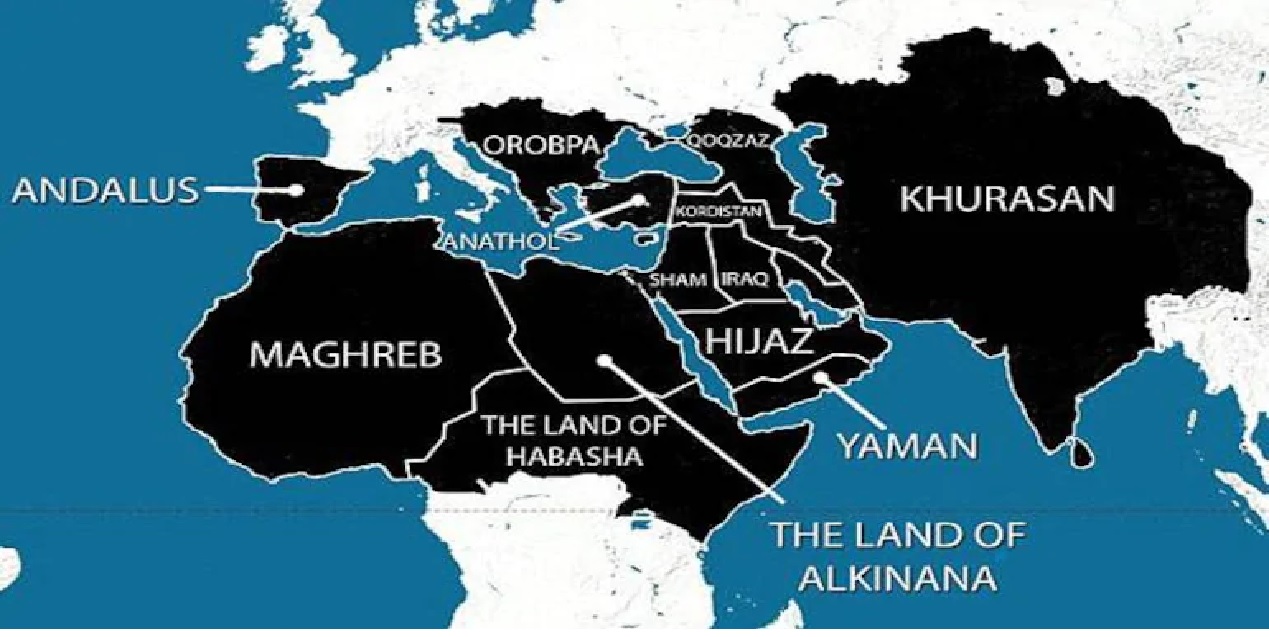

Even though there is an assertion that the ISIS is defeated, but the fact is that Islamic State has zeroed down on an external province by announcing ‘Wilayat’ for achieving its global objective. For this purpose, Africa has emerged as a continent from where IS can operate. IS has been conducting sophisticated attacks on Africa and successfully occupied territories with the assistance of their allies.

According to the Global Terrorism Index 2020 report, ‘seven of the ten countries with the largest increase in terrorism were in sub-Saharan Africa.’ Burkina Faso had the largest increase in terrorism, where deaths increased by 590 per cent from 86 in the previous year to 593 in 2020.

Al Qaeda

In Africa, IS has three large regions, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) in Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and Mali; Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) in Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique; and Islamic State Sinai Province in Egypt. There was also an Islamic State Algeria Province comprising al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) defectors. Al Qaeda has survived for more than three decades with constant evolving tactics, techniques, narratives, and modus operandi. Al-Qaeda has expanded its presence in Syria, Yemen, and Africa, including both the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. The group associates throughout the world continue to display the capability to launch attacks. In the beginning of January 2020, al-Shabab launched a truck bombing in Mogadishu, killing many people.15 AQAP carried out two attacks in February 2020, with one on the U.S Naval Air Station in Florida16 and another on Colonel Jamal Al Awlaki, a senior Yemeni counter-terrorism official, in Yemen.17

Al Qaeda lost some of its top leaders in the U.S. counter-terrorism operations starting from Afghanistan to Iran and Syria. Most notably, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah (better known as Abu Mohammed al-Masri), was allegedly killed in August by a team of Israeli assassins working on the directions of U.S. intelligence in Tehran.18 The killing of al-Masri, projected as the heir to Ayman al-Zawahiri, was one of the most significant operational successes against al-Qaeda since Osama Bin Laden's death in Abbottabad, Pakistan in 2011. Beyond the U.S.-Israeli operation, al-Qaeda has also recently lost its media chief, Hossam Abdul Raouf, Afghanistan,19 and Khaled al-Aruri (Abu al-Qassam al-Urduni) and Sari Shihab (Abu Khallad al-Mohandis) in Syria, among many others in 2017 and 2019 respectively.20

For now, no evidence exists to substantiate rumours of Zawahiri's death. What appears more likely is that due to ill health, Zawahiri has put himself temporarily out of combat, or that the ends of Abu Mohammed al-Masri and Hossam Abdul Raouf have compelled him to go underground. Given his evident basing in eastern Afghanistan, it is also possible that Zawahiri has been made to go off the radar by the Taliban leaders due tothe U.S.-Taliban agreement and the ongoing intra-Afghan peace talks.

Since the U.S. counter-terrorism victories against al-Qaeda leaders over the past nearly two decades, al-Qaeda has proceeded on the path of decentralisation. Today's al-Qaeda can be portrayed as a loosely networked movement, comprising like-minded but regionally distinct groups, each pursuing progressively local objectives. The Shura that Zawahiri represents wield a dominantinfluence and form a focal point for the cause; however, at present, the controlling and guiding power seems to slip out of the hands.

The spread of cyber influence and easy access to the Internet and frequency with which the strategic communication is being disseminated; has all contributed to an exponential progression in al-Qaeda's decentralisation.

Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), led by Iyad Ag Ghaly, a former Malian diplomat known as "the strategist," is an example of this trend. The groups' ideology differs little from that of al-Qaeda, but the operational methods have evolved since its inception. In parts of the Sahel region, particularly in northern Mali, JNIM has arguably won more favours and is accepted by the people in mediating in the conflict. Similarly, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), getting tribal coalitions and focusing on hostilities with the Houthis has emerged stronger.

Just like Osama bin Laden's post-assassination, Zarqawi evolved extreme agendas in Iraq; likewise, al-Shabab in Somalia has been excessively brutal. The trajectory appears to be focused on growing local and regional roots, and eventually transforming the population to fit Salafi-jihadist ideals in hopes of one day collectively forming an Islamic state under a Caliph.

Conclusion

Based on the evaluation, it can be assumed that the Islamic State is yet not defeated but remains highly active, particularly in Africa and in the Levant (especially in Iraq). The year 2020 proved to be useful for the Islamic State in Sub-Saharan Africa. On the basis of casualty per attack ratio ISWAP, ISCAP and Khorasan are the deadliest provinces.

In al Qaeda, there will be a struggle in the group to foster a new leader even if Zawahiri is alive. Because given the fact that the only surviving leader in the three-person council of deputies, Mohammed Salah ad-Din Zeidan (Sayef al-Adel), who is based in Iran has been placed under travel restrictions which are unlikely to be removed. It provides Iran strategically significant leverage while negotiating with both al Qaeda and the Biden administration, in case of resumption of negotiations over ceasefire and nuclear proliferation.

The future challenge could be that al Qaeda has become more decentralised and rooted in locally oriented jihadist propaganda. It may be correct to say that there will not be any 9/11 style attacks; however, at the same time, it does not mean the complete success of counterterrorism. Conversely, counter-terrorism operations have led to the group's adapting new strategies and using Cyber terrorism making it more difficult and further challenging.

The digital space has become a new battleground for ideological warfare; the radical groups are actively using it for recruitment, propaganda, and radicalization. Especially, during the pandemic period, internet became the latest weapon in the hands of violent radicals who used it to spread hatred against the government and civil bodies.

The new counter-terrorism strategies must include countering local issues of corruption, failed governance, and economic downturn, regional conflicts and under development which enables jihadists to recruit, expand and operate in silos.

COVID-19 has severely impacted the implementation of protection measures, prosecution, rehabilitation, reintegration (PRR) efforts, CVE programming, criminal-justice processes, and judicial procedures. In-person access to inmates has is restricted, and overcrowding is rampant. Experts from the Eurasian region have observed instances where terrorist and violent extremist groups have sought to exploit economic grievances. Most of these challenges are about the loss of employment by offering financial support to affected individuals (including offers to pay off debts or cover rent and utility expenses), perceiving this as an opportunity to indoctrinate or recruit them.

Endnotes

- Twenty-sixth report of the Analytical Support and Monitoring Team pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida, and associated individuals and entities (2020), United Nations Security Council, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2020_717.pdf.

- Eleventh report of the Analytical Support and Monitoring Team pursuant to resolution 2501 (2019) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability, and security of Afghanistan (2020), United Nations Security Council, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2020_415_e.pdf

- BBC News, ‘Islamic State group defeated as final territory lost, US-backed forces say’, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47678157, 23 March 2019.

- BBC News, ‘Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: IS leader ‘dead after US raid’ in Syria’, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-50200339, 28 October 2019.

- Frank Gardner, ‘Is Africa overtaking the Middle East as the new jihadist battleground?’, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55147863, 3 December 2020.

- START, 2020, ‘Global Terrorism Index 2020 Briefing’, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GTI-2020-Briefing.pdf

- Ibid.

- Beritbart, ‘‘Battle of Ramadan’: Jihadis Kill 584, Injure 587 in Three Weeks of Holy Month’, https://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2020/05/21/battle-of-ramadan-jihadis-kill-584-injure-587-in-three-weeks-of-holy-month/ (Accessed May 21, 2020)..

- Sunnah.com, ‘Chapter 76 Medicines- Chapter What has been mentioned about the plague’, https://sunnah.com/bukhari/76/43 (Accessed May 27, 2020).

- Vishal Tiwari, ‘US Withdrawing Forces from Somalia in Line with Donald Trump’s order: Pentagon’, Republic World, https://www.republicworld.com/world-news/us-news/us-withdrawing-forces-from-somalia-in-line-with-donald-trumps-order-pentagon.html

- Corbet, Sylvie, ‘France seeks strategy change to reduce troops in West Africa’, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/france-seeks-strategy-change-reduce-troops-west-africa-75110214, January 8, 2021.

- Miller, Olivia, ‘ISIS continues to Grow in Africa’, https://www.persecution.org/2020/12/25/isis-continues-grow-africa/, December 25, 2020.

- Tore Hamming, ‘The Islamic State 2020: The Year in Review’, http://www.jihadica.com/the-islamic-state-2020-the-year-in-review/. 31 December 2020.

- Jason Burke, ‘ISIS claims sub-Saharan attacks in a sign of African ambitions’, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/06/isis-claims-sub-saharan-attacks-sign-africa-ambitions-islamic-extremist, 6 June 2019.

- BBC News, ‘Somalia attack: Demonstration held in Mogadishu’, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50971759, 2 January 2020

- Colin Clarke, ‘The Pensacola Terrorist Attack: The Enduring Influence of al-Qaeda and its affiliates’, Combating Terrorism Center, Volume 13, Issue 3, March 2020, https://ctc.usma.edu/pensacola-terrorist-attack-enduring-influence-al-qaida-affiliates/

- Ali Mahmood, ‘Al Qaeda gunmen suspected in attack on home of Yemeni counter terrorism colonel’, The National, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/mena/al-qaeda-gunmen-suspected-in-attack-on-home-of-yemeni-counter-terrorism-colonel-1.976407, 11 February 2020

- Reuters. ‘Israeli operatives reportedly killed al Qaeda’s no. 2 leader in Iran in August’, CNBC-World Politics, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/14/israeli-operatives-reportedly-killed-al-qaedas-no-2-leader-in-iran.html, 14 November 2020.

- Thomas Joscelyn, ‘Afghan Forces claim senior al Qaeda lieutenant killed in Ghazni’, FDD’s Long War Journal, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2020/10/afghan-forces-claim-senior-al-qaeda-lieutenant-killed-in-ghazni.php, 24 October, 2020.

- Shan A Zain, ‘Abu Muhammad al-Masri-Next in Line to lead al Qaeda?’, Militant Leadership Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/July-2020_MLM.pdf, July 2020.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://akm-img-a-in.tosshub.com/indiatoday/images/story/201508/map-story_647_081015061820.jpg?size=770:433

Post new comment