The 38th Summit of the Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD) held in late December 2020, has been a focus of attention. This is unusual for the organisation. The IGAD is headquartered in Djibouti and was formed in 1986. The IGAD was revitalized by its leaders in 1996.

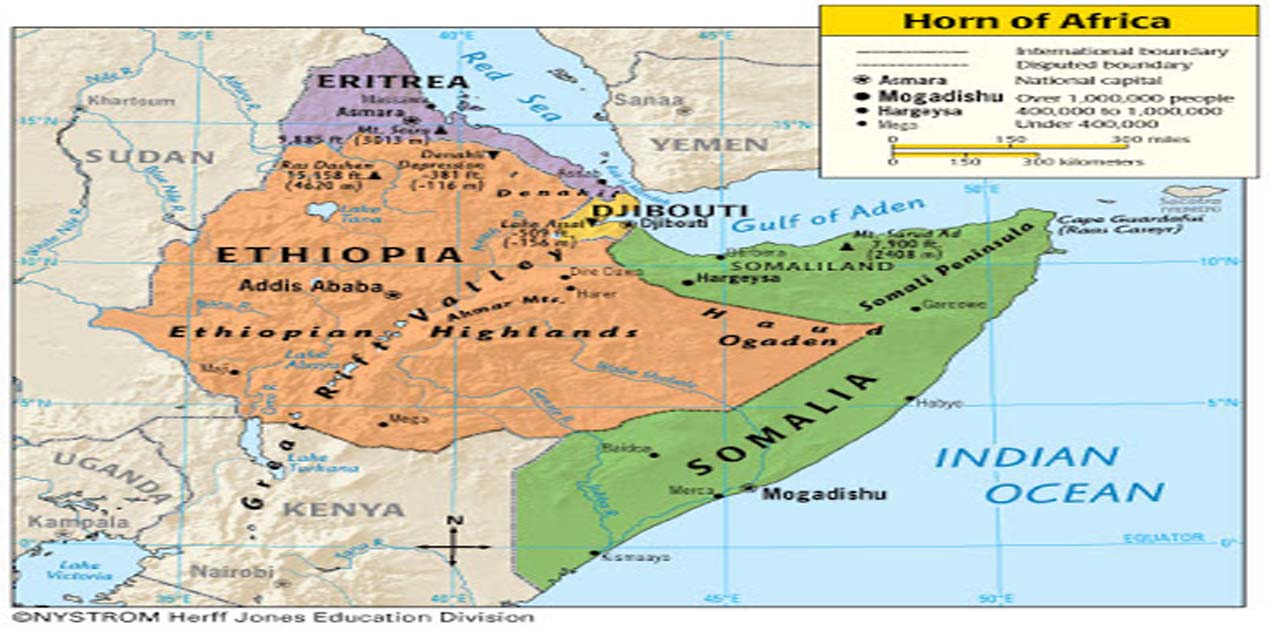

It originally had 6 members viz Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda, Sudan and Kenya. Eritrea joined when it seceded from Ethiopia in 1993 but withdrew in 2007 to rejoin in 2011, though it abstains from IGAD meetings. South Sudan joined after its separation in 2011.

It is one of the 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs) recognised by the African Union. However, it is not much of an economic community as most of its members are adherents of Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). South Sudan and Somalia are the two who are not within COMESA. Eritrea is the only country not in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan are part of the efficient East African Community. Thus, most members and partners look at IGAD as a development partner and since 2007 it has focused on security issues particularly in Somalia.

When no country wanted to get in to the Somalia imbroglio, the focus shifted to IGAD. In September 2006, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council approved an IGAD proposal to deploy an IGAD Peace Support Mission in Somalia (IGASOM). This was opposed by the Islamic Courts in Mogadishu but was financed mostly by the EU and had 8000 troops from Uganda and Ethiopia in the main. Within a year the UN Security Council authorised an AU mission to replace the IGASOM.

African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) has a mandate to support the operation of the transitional government, organise a national security plan, train the security forces, and to create a secure environment for humanitarian aid. Over the last 13 years it has maintained a tenuous peace, ably backed by donors and troops from Kenya and Ethiopia. Djibouti and Uganda from within IGAD and Burundi from without also have troops in AMISOM. So long as AMISOM maintains a semblance of order, interest in IGAD remains high.

The 38th Extraordinary session of the IGADS Heads of State and Government on 20 December however, comes amidst a varied set of security challenges to the region Workneh Gebeyehu the Executive Secretary of IGAD tweeted: As I addressed the #IGAD Summit of today, I reminded our leaders that the reg was seeking their wisdom & looked to their leadership to deliberate upon current issues & chart the way forward.

The IGAD Executive Secretary is an Ethiopian politician from Oromia State and was the Minister for Foreign Affairs from 2016 to 2019. He was announced as the Director General of the UN Office in Nairobi by the UN Secretary General but instead was preferred as the Executive Secretary of the IGAD showing the importance attached by Ethiopia to this organisation. For most years either Ethiopia or Kenya have chaired the IGAD and provided its executive secretary (ES). Kenya provided the ES from 2008 to 2019 and in these years, it was mainly Ethiopia which retained the Chairmanship. As a compromise the PM of Sudan is now the Chair of IGAD since November 2019. At the time of his election the Kenyan President was absent as was Eritrea. At the 38th Summit now, besides Eritrea remaining absent, the leaders of Uganda, and South Sudan sent representatives.

The 38th Summit was stated as having the civil war in Ethiopia and its refugee’s exodus to Sudan as the main agenda items. Then there was Covid and locusts which affect the region. Before the Summit, Somalia -Kenya relations came to a head and Somalia broke diplomatic relations with Kenya.

The current issues now go beyond the Somalia situation. The quasi separation of Somaliland and Puntland are among the challenges that Somalia faces as it rises to another election in 2021 as it could not be held in 2020. Djibouti is itself looking to another election in April 2021. Uganda was in the midst of pre-election violence for its election due on 14 January 2021. Kenya has elections in 2022 while Ethiopia has postponed its elections to 2021. Sudan is in a transitional government and South Sudan is holding on to a delicate arrangement. Eritrea seems the most stable of the IGAD member countries!

Be that as it may, the major challenges faced by IGAD are the ramifications of the Ethiopian civil war in Tigray which Ethiopia sees as a law enforcement action against a renegade province. The internal turmoil within Ethiopia has not played itself out fully and as the youthful Nobel Peace Prize winning PM Abiy Ahmed restructures Ethiopia, its elites and political system, ramifications in the region are emerging.

Let us analyse these. Abiy won the Nobel Peace Prize for achieving a peace agreement with Eritrea. This was indeed welcome as it settled a long pending matter. The two are now allied including in dealing with the Tigray situation. Ethiopia has successfully kept the Tigray situation out of the purview of the African Union as well as IGAD. The chairperson of the AU Commission and the IGAD are now mainly concerned with the flow of refugees into Sudan whose Prime Minister is the Chair of IGAD. Through deft diplomacy, Ethiopian ministers have met with the leaders of each IGAD country and explained their action and in most cases received support. Uganda has been ambivalent in its statements often altering them between their core desire to recommend peace and reconciliation and to avoid antagonizing the Ethiopian PM. Sudan, which already had a problem with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), now is overwhelmed by refugees from the Civil War. From the communiqué of the summit, it appears that Sudan did not get a solution to the refugee issue and can be expected to raise it in other fora and seek advantage. It has since physically taken over farmlands under Ethiopian cultivation for several years creating a live situation on the Sudan Ethiopia Border.

Uganda is currently busy with its presidential election and with a smaller troop contribution to AMISOM; it is likely to follow whatever decisions are ultimately taken. The same applies to Djibouti but it is more wary of an Eritrean role which, following its rapprochement with Ethiopia is now seeking a role in Somalia which Djibouti is anxious about. Djibouti also realised that Ethiopia may seek alternative ports to it from Eritrea and in Somaliland. The LAPPSETT corridor between Kenya, Ethiopia, South Sudan inaugurated in December 2020 is another challenge and shows the collaborative spirit among Kenya and Ethiopia too.

South Sudan is busy in its own reconciliation and is not showing any major sign of taking sides though it is being wooed particularly by Egypt to see its point on the GERD with Ethiopia.

But all the king’s horses and all the king’s men need to put together Somalia again. The delayed election is causing President Farmaajo to take exceptional positions, this time against Kenya. Prior to the last election he had taken similar positions with Ethiopia but not gone as far as to briefly break diplomatic relations. Moreover, Kenya has paid the biggest price in fighting terrorism and the Islamic State in Somalia through its military support to AMISOM. Under no circumstances would Kenya like to withdraw its forces and allow inimical elements to gain ascendancy which is likely if a strong AMISOM is disbanded. Already Ethiopia has withdrawn 4000 troops which were not directly part of AMISOM, that has created a security vacuum in Somalia.

Somalia views Kenya as interfering in its internal affairs and is reducing its acknowledgement of Kenyan support for its stability. Presently, it is aligning its self more closely with Ethiopia, which brings along with it, Eritrea and Djibouti and the tensions between them. Kenya thinks the Ethiopian action is not in consultation with it, which has been the hallmark of IGAD deliberations and AMISOM deployment. The breach of diplomatic relations by Somalia has also led to the demand for removing the Kenyan contingent from the AMISOM. The suspicion is that they would welcome an Eritrean contingent but overlooks the fact that the host country does not have a choice among troop contributing countries. This remains the prerogative of the sending organisation, in this case the UN and the AU. The donors who contribute to the upkeep of AMISOM also have a say and Eritrea has not inspired confidence in the international community to be a responsible player so far. If Eritrea can play a significant positive role then that would be a big gain for the region for which gratitude would have to be granted to the EthiopianPM for the thaw with Eritrea.

The proceedings and unrecorded disagreement at the summit, indicates that the AMISOM and the Somalia situation needs to be handled delicately. It’s significant as it shows alterations in regional dynamics. The traditional domination of the region by Kenya and Ethiopia is now showing divergence among them and other countries are wondering what the best is for them. If Ugandan President Museveni is re-elected, he is then expected to play a bigger role to mediate the crisis.

Another problem of the region is the fact that it has seen the creation of new countries more than any other region in Africa. Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993 and South Sudan from Sudan in 2010. Both have led to an unsettled situation thereafter, leaving anxiety in the region. Similarly, the quasi autonomy of Somaliland, Puntland and possibly Juba land are troublesome for Somalia though various countries in the region have established engagement with these relatively more stable parts of Somalia.

The international community is now faced with underlying competition emerging from West Asia into the region. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are competing with Qatar while Turkey and Egypt are part of the competitive arrangements. Turkey has robustly sided with Qatari interests in the region, changing positions as required and challenging the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt nexus. The latter extends to curbing inimical forces in Yemen, across the Horn of Africa and also has ramifications in Libya. With the war in Tigray, Ethiopia is also realigning and since Eritrea is in alliance with the UAE, and Djibouti does not, the contradictions in the region increase. The entry of Eritrea as part of AMISOM will not go down well with Qatar and Turkey and hence the new intervention that Ethiopia is planning will have many ramifications whose prognosis cannot be easily settled.

Sofar, the alliances between Gulf States, Turkey and the countries of IGAD have followed a broad pattern but that pattern is more likely to change following the Ethiopian civil war. It will also call into question the role of Egypt which is antagonistic to Ethiopia but close to Eritrea and the UAE who are now coming closer to Ethiopia.

Diplomacy is always the challenge to aggregate all of a country’s interests and strengths and seek the best possible position for it. Though Ethiopia had dominated the Horn of Africa region in a partnership with Kenya, but now it seeks a new alignment, which Kenya may not be an integral part of. On its part, Kenya is unlikely to give up the gains it has made and may seek a wider alignment with Uganda and others to balance the situation. Kenya will not forget in a hurry that its quest for a seat on the UN Security Council was challenged by Djibouti from the same region and it took two rounds of voting to finally make it. At the United Nations Kenya will have a bigger say from January 2021 and it needs to use that to buttress its regional position. In all this the role of the African Union is being closely watched to see whether it can finally be an effective interlocutor.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-VnMcFwLTp4c/T8HloacLzAI/AAAAAAAACLA/-Q3SKuyYW6E/s400/Horn-Africa-Map.jpg

Post new comment