Introduction

In recent times, the Indo-Pacific region has attracted considerable attention of strategists and security analysts because of the rise of China with its muscle-flexing activities and assertiveness in regional affairs, which threaten to upset existing equilibrium and therefore demands appropriate response by all stakeholders. Besides this emergence as a major talking point among leading regional and global powers, discussions have centred on how to cope with this new challenge so that the national and security interests of the nations affected by China’s aggressive and unilateral actions are not adversely affected. Several bilateral, regional and multilateral initiatives have been adopted to address this issue but none of these have proved to be effective to address this critical issue. One such initiative taken up by four leading stakeholders – India, the US, Japan and Australia – in evolving a dialogue mechanism, popularly known as Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Initiative or Quad needs close scrutiny.

Concept of Indo-Pacific

First, what is this Indo-Pacific and how does one define it? As the term suggests, it is geographical connotation covering both the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. The term ‘Indo-Pacific’ was used for the first time by the noted Indian scholar/historian Kalidas Nag in his 1941 famous book India and the Pacific World.1 For him, the term referred to largely a cultural and civilizational entity. Nag had the impulse to trace India’s links with the maritime universe and joined Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore in his voyage to China. The term ‘Indo-Pacific’ was largely out of academic lexicon until it was resurrected when Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shino in his address to Indian Parliament in August 2007 on the ‘Confluence of the two Seas” used the term Indo-Pacific.2 Since then recent developments with China’s emergence as the new power house has led analysts and academics to pick up the term and dissect its various nuances with rigour.

Since then, various security analysts have used the term Indo-Pacific in different context. The debate on this topical issue is because of the fact that the centre of world’s gravity in economic matters has dramatically shifted towards the Asian continent. In this matrix, the emergence of China and India, both economically and in strategic realm, have shaped thinking of other nations in the geo-economics, in which the importance of both the Indian Ocean and the Pacific assume greater strategic significance. The concept was further popularised by former diplomat TCA Raghavan whose study underlined the changing seas and greater importance of maritime trade in the Indo-Pacific region and the importance of securing the same.3

In his article, Raghavan mentions that Abe invoked Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, and the title of a Sufi text he authored in 1655 Majma-ul-Bahrain, which translates as “Mingling of the Two Oceans”. Though Dara Shikoh was seeking common ground between the two religions of Islam and Hinduism, Abe used the metaphor for a “broader Asia”, one in which the “Pacific and the Indian Oceans are not bringing about a dynamic coupling as seas of ...prosperity”. Abe envisioned a greater role of India and Japan in this changing matrix.

Against this background, the current interest in the concept has gained greater currency as the Chinese military and maritime footprint cross the littorals of the Indian and Pacific Oceans has emerged as a matter of concern, which is why the evolution of the Quad gains greater salience.

How far the Quad Initiative has progressed?

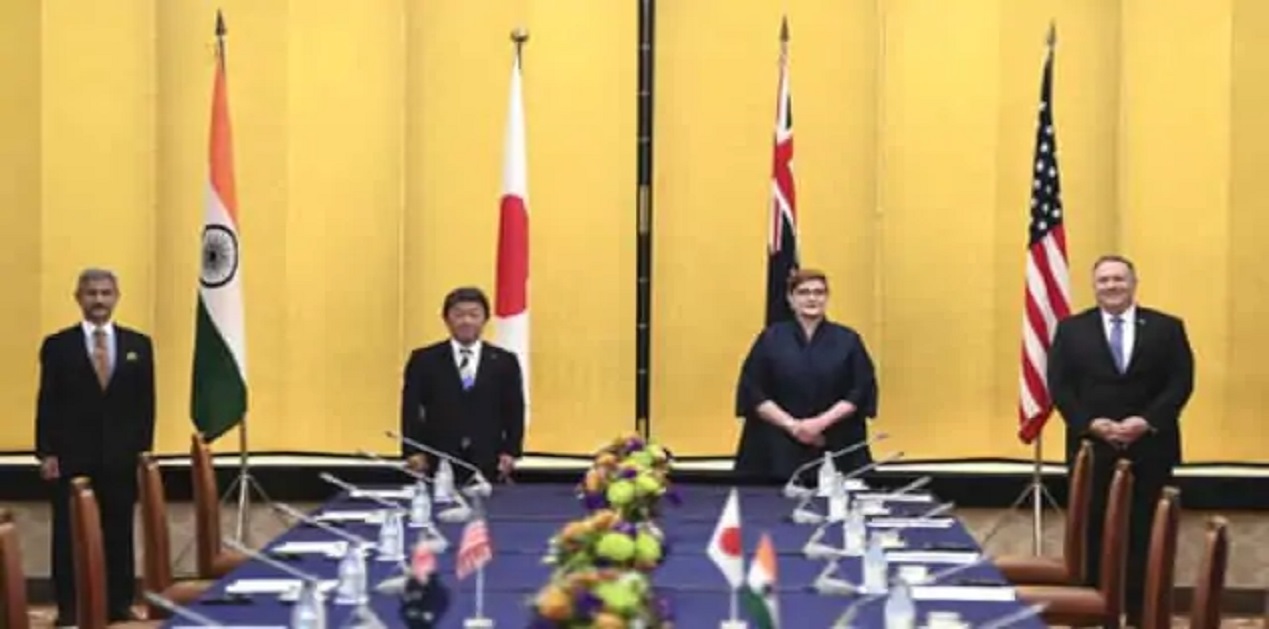

As the Chinese military and maritime footprint continues to expand, there is a greater need for the Quad nations to engage in continuous dialogue and share views on how to cope with the new situation. One thing is clear: the Quad nations oppose China’s attempts to alter status quo by force.4 As a result, the foreign ministers of the four Quad members are now meeting regularly to address the challenging issues. They met for the third time early in February 2021, after September 2019 and October 2020, when the mechanism was revived at the level of officials in 2017, wherein they flagged a “free and open Indo-Pacific region, including support for freedom of navigation and territorial integrity”.5

When the concept was first floated in 2007, there was hesitation in certain quarters in India and in Australia and after Abe suddenly resigned owing to health issues, the concept was buried until it was resurrected in 2017. Yet, even after two Foreign Ministers’ level meeting, India had refrained from even using the word “Quad”. But this time during the third meeting, India shed such hesitation and used the term Quad for the first time to describe the grouping, thereby signalling a possible counterweight to China’s aggressive move in the region. Earlier, the MEA had always mentioned the interactions as “meeting of the four countries”.

The official statement issued after the meeting underlined Quad’s “commitment to upholding a rules-based international order, underpinned by respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, rule of law, transparency, and freedom of navigation in the international seas and peaceful resolution of disputes”. This was a clear reference point to China’s moves. The ministers also highlighted their “shared attributes as political democracies, market economies and pluralistic societies”.

It is significant to note that the third meeting of the Foreign Ministers was the first during the new Joe Biden administration, thereby signalling continuity in their common approach on dealing with an assertive China. The meeting was attended by India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Australia’s Foreign Minister Marine Payne and Japan’s Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi. Prior to the meeting of the Foreign Ministers, Prime Minister Narendra Modi also spoke with his Australian counterpart Scott Morrison, during which both promised to “work together for peace, prosperity and security in the Indo-Pacific”. Later, the MEA statement underlined “clear support for ASEAN cohesion and centrality”. The Indo-Pacific concept has also garnered international support in Europe with France, Germany and the UK extending endorsement.

Other members of the Quad grouping also flagged similar opinions. While the US stressed in a statement the need for a “a “free and open Indo-Pacific region, including support for freedom of navigation and territorial integrity”, Japan’s Motegi expressed “serious concern with regard to the China’s Coast Guard Law” and said that “the four Ministers concurred to strongly oppose unilateral and forceful attempts to change the status quo in the context of the East and South China Sea”.

While there is no dispute that the China factor is the main issue that is driving the Quad grouping to seek common viewpoints and strategy, the ambit of the discussion does not remain confined to China alone but has embraced other regional issues such as combating Covid-19 and the way to deal with the recent developments in Myanmar that have threatened the centrality of the ASEAN and undermine democracy.6 In this context, while Jaishankar reiterated “upholding of rule of law and the democratic transition”, Blinken spoke about “the urgent need to restore the democratically elected government in Burma (US still uses Burma and not Myanmar)”, and Motegi “expressed grave concern for deteriorating situation” in Myanmar. While expressing concern with the development in Myanmar, Motegi “strongly urged(ing) the Myanmar military to immediately stop violence against citizens including shootings, release those who have been detained including State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and swiftly restore Myanmar’s democratic political system”.

Other issues the Quad leaders discussed included efforts to combat the Covid-19 pandemic, including vaccination programs and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicine and medical equipment. India’s efforts at providing vaccines to 74 countries was recognised and appreciated. The ministers also exchanged views on responding to climate change and furthering cooperation in areas such as maritime security, HADR, supply chain resilience, counter-terrorism and countering disinformation, thereby prioritising strengthening democratic resilience in the broader region. North Korea’s nuclear and missile development issues also figured in the discussion. In short, the broad ambit of the discussion embraced issues that could be for “global good”.

Critics see the QUAD as a kind of Asian NATO. The grouping is also being seen as a new architecture aimed at checking the China’s perceived threat. Neither has any merit, if the discussions in the preceding para detailing the host of issues, not just security, that were discussed by the ministers are taken into account, the aims are larger than critics perceive.

Allaying Russia’s Reservation

India had to deal carefully with Russia, which sees Quad as China-centric, because Russia is a long-lasting friend of India and would not allow such misperceptions to derail bilateral relationship. Russia refuses to use the term Indo-Pacific, saying that the concept is divisive in nature. Clarity emerged when Foreign Secretary Harsh Shringla visited Russia, his first overseas trip in 2021, and explained the merit of the Quad, while being assured by Russia that its latest engagement with India’s rival Pakistan focussing on the development of Afghanistan will not impinge at all on ties with India or be detrimental to India’s security interests. On his part, Shringla allayed Russia’s apprehensions about the Indo-Pacific by emphasising that it is a free, open, transparent and inclusive initiative with ASEAN at its centre and that it does not exclude any country.7

With a view to allay Russia’s reservations about the Quad concept, two of the Quad members – India and Japan – got Russia on board for a trilateral Track-II to work together for joint investment and development of projects in the region.8 While this initiative shall address some of the territorial issues that Japan and Russia have, the trilateral initiative shall help New Delhi’s vision of making the Indo-Pacific strategic initiative ‘inclusive and not just against one country’. The initiative has a strategic dimension too as it helps to broaden the outreach of the Quad member states. Since Russia too is a Pacific power and an important player on Indo-Pacific affairs, keeping Russia suspicious of the Quad initiative could work negatively for Quad’s future. It would be prudent and in the interests of all stakeholders of the Quad concept to keep Russia on board.

Future

Quad is still in the evolutionary process. Its future direction and role can depend on what geopolitical churning takes place in the coming months and years. Though at present it is difficult to say if Quad can play the role of a net security provider to the Indo-Pacific region, the vast canvas it has embraced thus far can be seen as a welcome prospect that shall contribute to the peace, security and economic development of the larger Indo-Pacific region. As other countries start seeing the Quad as a result-oriented initiative, its robustness would have been further strengthened.

Endnotes

- See, Kalidas Nag, India and the Pacific World (1941), Book Company Ltd, pp. 318.

- "Confluence of the Two Seas", Speech by Abe Shinzo in Indian Parliament, 22 August 2007, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

- TCA Raghavan, “The changing seas: antecedents of the Indo-Pacific”, The Telegraph, 17 July 2019, https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/the-changing-seas-antecedents-of-the-indo-pacific/cid/1694598

- “Quad nations oppose China's attempts to alter status quo by force”, The Japan Times, 19 February 2021, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/02/19/national/quad-nations-china-indo-pacific/

- Shubhajit Roy, China on mind, Quad ministers want respect for territorial integrity, Indian Express, 19 February 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/china-on-mind-quad-ministers-want-respect-for-territorial-integrity-7194897/

- See, Rajaram Panda, “Myanmar: India’s choices are limited”, 17 February 2021, https://www.rediff.com/news/column/rajaram-panda-myanmar-indias-choices-are-limited/20210217.htm

- Sachin Parashar, “Talks with Pak only on Af, won’t hurt India: Russia”, Times of India, 21 February 2021.

- Nayanima Basu, “India, Japan in talks with Russia to create trilateral & push Modi’s ‘Act Far East’ policy”, 28 January 2021, https://theprint.in/diplomacy/india-japan-in-talks-with-russia-to-create-trilateral-push-modis-act-far-east-policy/593402/

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://images.firstpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Quad_Tokyo640.jpg?impolicy=website&width=640&height=363

Post new comment