The narrative about the ‘peaceful Rise of China’ is ironic. China has border disputes with all its neighbours. Some of these issues have been addressed, while some still exist. For example, its border dispute with India is a critical issue affecting the bilateral relations. On the other hand, China’s disputes with its Central Asian neighbours have been resolved but with conditions attached to them. Beijing’s deep economic engagement has helped it enhance its strategic leverage in Central Asia. However, deeper Chinese penetration in the region has also led to severe consequences, especially for Central Asia’s low-income, remittance-based economies. Tajikistan has become the victim of economic over-dependence on China. China’s relations with Tajikistan have led to fewer economic benefits and more of geopolitical concerns, especially in the shape of land encroachment and debt trap.

Tajikistan’s Geostrategic Location is Critical for China’s Internal Security

China’s relationship with Soviet Central Asia left a lot to be desired. During this period, the Central Asian leadership viewed China with suspicion. However, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the Chinese aspiration to connect with the Central Asian region was facilitated based on the socio-economic necessities of the latter. Central Asia was critical for China in maintaining political stability in Xinjiang that shares a border with both Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Uyghurs, a Muslim ethnic minority group, are facing the wrath of repressive Chinese policies in Xinjiang. Voicing their dissent, they were termed terrorists by the Chinese government. Central Asian countries have ethnic-cultural similarities with Uyghurs. China was apprehensive about Uyghurs getting any support from this region.

Having a close relationship with Tajikistan was an added advantage for Beijing to keep an eye on East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) activities in Afghanistan. A year after Tajikistan's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, China and Tajikistan established diplomatic ties. Since then, the cooperation between the two nations in economic, security and international affairs has grown. At times, the governments of both countries have claimed that the shared border will mark peace and goodwill between the two geographical neighbours, political allies, and economic partners.

Through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China swayed Tajikistan to combat the ‘three evils’ that are terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism. Tajik Parliament ratified an Extradition Treaty with China in 2015.1 Following the deportation of Uyghurs to Tajikistan by Turkey in 2019, they were quickly repatriated to China, where they were arrested upon arrival. It is also one of two Central Asian countries to sign a letter to the United Nations supporting Beijing's Xinjiang policy.2 Taking advantage of Dushanbe’s vulnerabilities, China has allegedly established a military base in Tajikistan’s Badakhshan province to monitor the strategically vital Wakhan Corridor.

Secondly, to import the hydrocarbon resources from Central Asia to fulfill the needs of its rapidly increasing industrial and manufacturing sector, China has invested in multiple oil and gas pipelines. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are the major oil and gas suppliers, while Uzbekistan also exports a moderate quantity of natural gas to Beijing. Almost seventy percent of exports of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan’s raw materials go to China.3 Tajikistan is also a transit country to Line D of the China-Central Asia gas pipeline, which is under construction. Furthermore, although BRI was announced in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan became the first country to sign an agreement with China for building the Silk Road economic belt (SREB). Thus, Tajikistan is geo-strategically crucial for China not as a transit route but also as a supporter of its counter-terrorism initiatives.

Why does Tajikistan favour China?

Tajikistan is a landlocked Central Asian country that shares borders with China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, Uzbekistan in the west, and Kyrgyzstan in the north. Almost 93 percent of its territory is rough, remote, and mountainous. Ferghana Valley is the only exception which is fertile and densely populated. Tajikistan shares 1357 km of the long and porous border with Afghanistan, making it significant for significant powers, including China.4 Tajik economy is remittance based; around 1 million Tajiks work in Russia. Therefore, any shock to the Russian economy has a direct impact on it. Western sanctions against Russia post-Crimean crisis in 2014 and COVID-19 pandemic are two significant events that significantly impacted Russia’s economy. Consequently, Tajikistan was also dearly affected. The poor economic condition of Tajikistan is the rationale behind the Chinese expansion.

Tajikistan has a Soviet-era autocratic leader. Post-Soviet Union’s collapse there have been many challenges to President Rahmon’s Presidency. Tajik civil war and religious fundamentalism are two of the main challenges that he faced. Along with that, poverty remains a major challenge. In order to sustain his regime, he needs to maintain economic growth along with infrastructural development. However, Russia’s domestic vulnerabilities made it impossible to support Tajikistan economically. Also, inhospitable geographical terrain in Tajikistan refrained investors from investing in infrastructure development in the country. This has provided a chance for China to pull in. However, Chinese expansion in trade and investments has led to severe consequences for the country.

Debt Trap Diplomacy

In order to get quick political and economic expansion across the globe, China dispenses concessional loans to the developing countries. They are often lured by China’s cheap loans for transformative infrastructural projects, requiring considerable investment. However, these countries, primarily low- or middle-income countries, remain incapable of carrying on with the repayments. Thus, this provides a golden opportunity for Beijing to demand concessions or advantages in exchange for debt relief. This is China’s debt entrapment pattern in Central Asia and more prominently in South Asia and Africa.

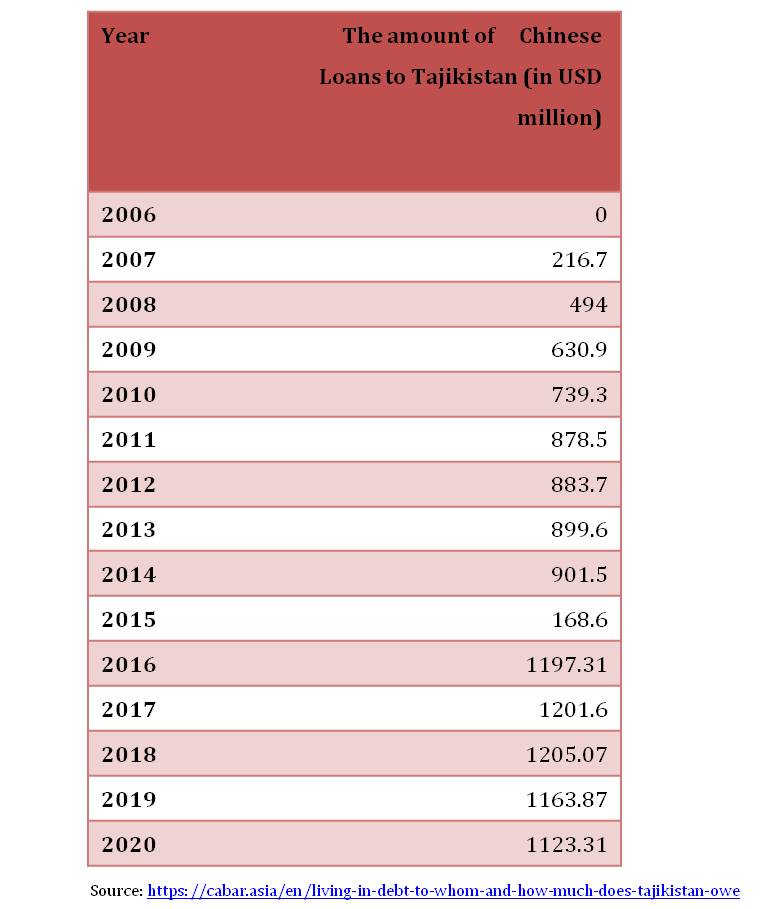

Beijing is one of the major trading partners of Tajikistan. In 2019 the bilateral trade amounted to around 700 million. China’s cumulative investment in Tajikistan from 2005–2018 was 1.61 USD billion, almost in the form of loans, according to the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).5 China remained Tajikistan’s largest source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), with a 75 percent share in total FDI, mainly in the country’s gold mines.6 Tajikistan’s total foreign debt was 2.89 billion USD as of the end of June 2019, as per the World Bank.7 But by October 2020, it reached 3.163 billion USD.8 Tajikistan owes 1.13 billion USD to the Exim Bank of China as of July 2020.9 This accounts for forty-one percent of the total foreign debt of Tajikistan.10 The first Chinese loan that Tajikistan obtained was in 2007, and the amount was 216.7 million USD.11

As clearly visible, China has become Tajikistan’s biggest debt-holder and its largest investor. However, being a remittance-based economy, Tajikistan is not capable of repaying these loans. As a result, it has to make compromises with China.12

Ceding of Mining Rights

Tajikistan’s unrelenting debt crisis has forced it to grant Chinese companies rights to mine gold, silver, and other mineral ores. In Tajikistan, the Chinese Tebian Electric Apparatus Stock Co. Ltd (TBEA) has acquired the rights to develop the Upper Kumarg goldfield in the Sughd province. Even before this, the company had access to the Duob goldfield, located in the Sughd province. As per the agreements concluded between both sides, TBEA has the right to extract precious metals from these mines until the Tajik side reimburses the funds spent for constructing the Dushanbe-2 heat and power plant.13

Sino-Tajik Border: Settlement or Entrapment?

The Sino-Tajik territorial dispute revolved around Chinese claims to the areas in the eastern Pamirs, which was under Tajikistan's de facto control within the Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO). The Pamir dispute can be dated back to the second part of the nineteenth century when Russian and Chinese empires had signed multiple treaties to demarcate their border. Treaty of Peking (1860), Protocol of Chuguchak- (1864), and Treaty of St. Petersburg (1881) are few to mention. However, during the Soviet era, border talks on the Pamir section were unsuccessful, and the vast stretch in this area remained unresolved.14

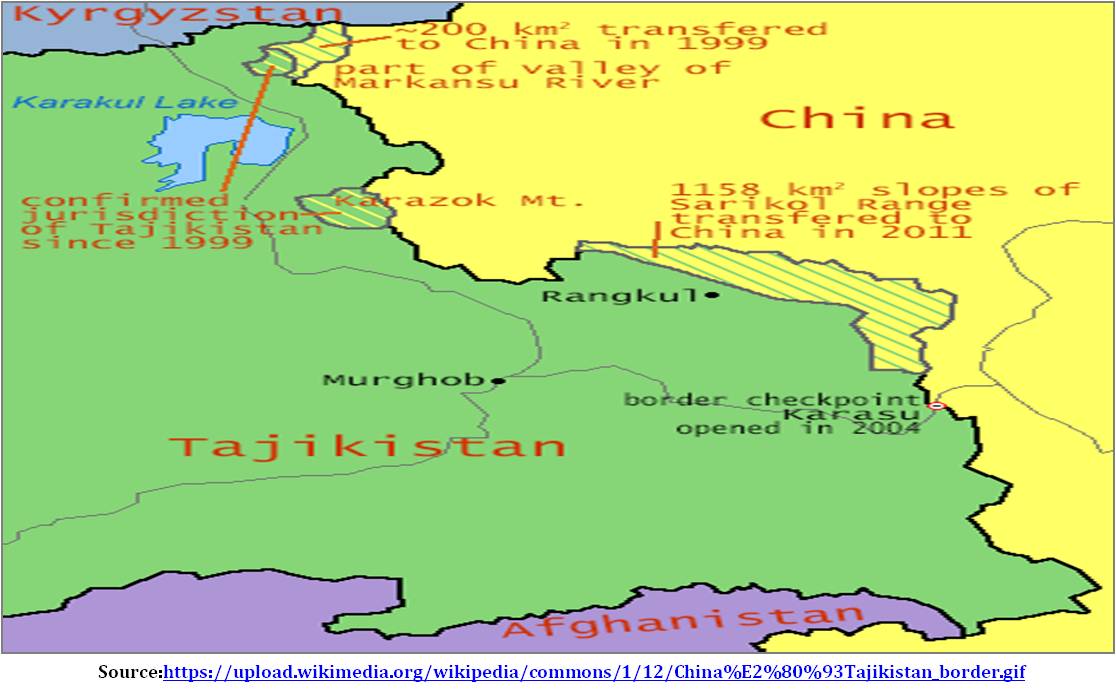

Post-Soviet disintegration, Tajikistan and China started negotiations on the disputed territories. In 1993, a Joint declaration to demarcate the border was signed. There were three points of contention- the largest was in the Pamir region (28,000 sq. Km).15 Two others were- the Markensu river section and the Karazakh Pass section, which jointly comprised more than 400 sq km. These two smaller issues were settled in 1999 by signing a Tajikistan-China border agreement. The Markensu river section was divided between Tajikistan with a 32 percent share and China with 68 percent. China relinquished its claims to Karazakh Pass.

To settle the dispute in the Pamir region, in 2002, a Supplementary Border Agreement was signed.16 According to this agreement, Tajikistan was forced to transfer 1122 sq. km land to China, which was 4 percent of the total 28000 sq. km of alleged claims in Pamir.17 In addition, the border demarcation protocol was signed in 201018, and in January 2011, Tajik Parliament ratified this Protocol.19

Ratification of Border Demarcation Protocol in Tajik Parliament

The Protocol's ratification process went reasonably uncomplicated, with Tajik parliamentarians voting mainly in favour of it. During his speech, Tajik Foreign Minister Hamrokhon Zarifi emphasized that this agreement favoured Tajik people as only a tiny part of the land was given to what China claimed. However, there were a few who disagreed. Two members of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) voted against its ratification.20 Muhiddin Kabiri, the leader of the IRPT, expressed strong protest, accusing the Tajik government of compromising the country’s sovereignty.21 The IRPT was the only legal Islamic political party in Central Asia and the second-largest political party in Tajikistan. Later in 2015, the Tajik government banned the party, labelling it as a terrorist organization.22

Tajikistan was full of persistent rumours that Dushanbe had given these lands to Beijing to pay off debt, although officially, the agreement pertained to demarcating the disputed border. The public opinion was negative in this regard. The Tajik public was unhappy with the ratification of this agreement. However, Tajik media played an essential role in building a positive environment revolving around the ratification of this Protocol. Tajik media is pro-government, so there was not much hype about this issue. Also, the strict authoritarian rule in the country had not allowed protests and demonstrations.

Chinese Belligerence and alleged Claims on Pamir

Recently, Chinese propaganda regarding alleged Chinese claims on Tajikistan’s Pamir region grabbed attention. An article titled ‘Tajikistan initiated the transfer of its lands to China, and the lost Pamir Mountains were returned to their true owner’ was frequently published in the state-controlled Chinese media.23 In this article, nationalist historian Chu Yao Lu made Chinese claims on the Pamir region based on Chinese sources. The opinion of Tajik historians or references to other relevant historical documents was not taken into account. This article has further aggravated the fears regarding Chinese entrapment. Tajikistan registered its objection to the Chinese envoy. Later the article was removed from the Chinese websites.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rising nationalism in China has led to this kind of propaganda. It dented Beijing’s reputation as a trusted partner. Consequently, China initiated a multilateral consultative mechanism (C+C5) with Central Asian countries. Although SCO has been vital in enhancing China’s influence in Central Asia, this new mechanism was targeted mainly for post-pandemic economic recovery and China’s vaccine diplomacy.

Implications for India

Tajikistan is India’s Gateway to Central Asia, which is separated by the Wakhan corridor in Afghanistan. Tajikistan's Ayni Airbase, which was rebuilt with India's assistance, is strategically important to New Delhi. India sought to use this airbase jointly, but due to Russia, China and Pakistan, Tajik Government did not allow it. India’s attempt to rebuild its relationship with Tajikistan is often viewed to counter China’s presence in the region. However, the trend suggests that Beijing has been apprehensive of India’s actions in Central Asia and Afghanistan. The evolving situation in Afghanistan again presents an opportunity for policymakers in India to engage with Tajikistan on defence and security issues.

China has also opened an airport in Tashkurgan in Xinjiang, near the borders of Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Tashkurgan city is the last famous destination on the Karakoram highway before entering Pak-Occupied Kashmir (PoK). The building of a Chinese airport is a matter of concern for India. It is the first such airport near the Gorno-Badakhshan region, which will give China new access to the peoples and natural resources of this much-contested area. However, China claims that Tashkurgan airfield is intended to promote tourism, but this claim stands superficial. An increasing Chinese influence in Tajikistan is strategically challenging for India's foreign policy objectives. In this context, India-Russia cooperation has the potential to counter China's progress. New Delhi needs to remain invested in Central Asia even though it has smaller outcomes. Moreover, India’s continued presence in the region is essential for long-term strategic benefits.

Conclusion

The second President of the United States of America, John Adams, famously claimed that a country might be captured and enslaved using the sword or debt. China employs the second method. At least 350 Chinese firms operate in Tajikistan, allowing Chinese citizens to relocate there. As more Chinese come to Tajikistan, they will be able to exert influence on the Tajik government and effect changes that benefit China. The current scenario in Tajikistan suggests that China is gradually expanding its influence over Tajikistan through debt diplomacy.

The COVID-19 has further worsened this disparity in China-Tajikistan ties. Tajikistan has already given land and mining rights and even authorized the Chinese military base as debt repayment. As a result, China is using a developing country as a weapon to advance its imperialist goal. There is a slight possibility that the BRI has given employment to many Tajiks. However, the costs caused by the BRI outweigh the apparent benefits of the Chinese enterprise. As a result, other nations who rely on China should learn from Tajikistan and avoid making the same mistakes.

References

- ‘Tajikistan has ratified an extradition treaty with China’, Silk road News, 29 January 2015. http://silkroadnews.org/en/news/tajikistan-has-ratified-an-extradition-treaty-with-china

- Bradley Jardine, ‘Emerging Forms of Pax Sinica in Tajikistan and Cambodia’, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 8 March 2021. https://www.fpri.org/article/2021/03/emerging-forms-of-pax-sinica-in-tajikistan-and-cambodia/

- Pravesh K Gupta, ‘China's Debt Trap in Central Asia’ Article, Vivekananda International Foundation, 1 October 2021. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2020/october/01/china-s-debt-trap-in-central-asia

- Gupta PK, ‘Why are Central Asian countries wooing Pakistan? Article. Vivekananda International Foundation. July 15 2021. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2021/july/15/why-are-central-asian-republics-wooing-pakistan

- Kazantsev, Andrei, Svetlana Medvedeva, and Ivan Safranchuk. “Between Russia and China: Central Asia in Greater Eurasia.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 12, no. 1 (January 2021): 57–71. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1879366521998242

- Tajikistan: Country Economic Update Fall 2019 Heightening Fiscal Risks in Tajikistan’, World Bank Report. Fall 2019. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/117701575020953951-0080022019/original/Tajikistaneconomicupdatefall2019en.pdf

- Ibid.

- ‘Living in Debt: To Whom and How Much Does Tajikistan Owe?’, CABAR Central Asia, 17 February 2021. https://cabar.asia/en/living-in-debt-to-whom-and-how-much-does-tajikistan-owe

- Pravesh K Gupta, ‘China's Debt Trap in Central Asia’ Article, Vivekananda International Foundation, 1 October 2021. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2020/october/01/china-s-debt-trap-in-central-asia

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Torunika Roy, ‘BRI and China’s Debt Trap Diplomacy: A Case Study of Sino-Tajik Relations’, Red Lantern Analytica. https://redlanternanalytica.com/editorialss/bri-and-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy-a-case-study-of-sino-tajik-relations/

- Pravesh K Gupta, ‘China's Debt Trap in Central Asia’ Article, Vivekananda International Foundation, 1 October 2021. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2020/october/01/china-s-debt-trap-in-central-asia

- A Bitabarova, ‘Contested views of contested territories: How Tajik society views the Tajik-Chinese border settlement’, Eurasia Border Review 6 (1), 63-81. https://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/60806/1/EBR6_1_004.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Bhavna Singh, ‘Sino-Tajik Border: Settlement or Entrapment?’ IPCS, 28 Jan, 2011 http://www.ipcs.org/focusthemsel.php?articleNo=3319

- Alexander Sodiqov, ‘Tajikistan Cedes Disputed Land to China’, Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 16, January 24, 2011. https://jamestown.org/program/tajikistan-cedes-disputed-land-to-china/

- ‘China, Tajikistan sign border demarcation protocol’, 29 April 2010. http://www.china.org.cn/world/2010-04/29/content_19933930.htm

- ‘Tajikistan ratifies border agreement with China’, Global Times, 14 January 2011. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/612563.shtml

- A Bitabarova, ‘Contested views of contested territories: How Tajik society views the Tajik-Chinese border settlement’, Eurasia Border Review 6 (1), 63-81. https://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/60806/1/EBR6_1_004.pdf

- Ibid.

- Casey Michel, ‘Trouble in Tajikistan’, Al Jazeera, 5 November 2015. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/5/trouble-in-tajikistan

- Pravesh K Gupta, ‘Tajikistan: Another Victim of Chinese Belligerence in Central Asia’, Article, Vivekananda International Foundation, 12 August 2020. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2020/august/12/tajikistan-another-victim-of-chinese-belligerence-in-central-asia

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://thediplomat.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/thediplomat-rahmon-xi-2019.jpg

Very helpful for studying international affairs.provided deep analysis.

Post new comment