There was a flurry of analyses in the wake of the 03 April 2021 clash between India’s Security Forces [SFs] and the Maoist insurgents at the Sukma-Bijapur border region in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh.123Barring a few4, the publications carried more of rhetoric and opinion than substance5. In fact, the way in which analysts and authors castigated the top brass of the SFs – in turn aided and abetted the cause of the Maoists – as if the propaganda war was being carried out on behalf of the insurgents by some intellectuals in the country.

A rather interesting aspect is that about a year ago, on 21 March 2020, in a clash with the insurgents at Sukma in Chhattisgarh, 17 SFs personnel were killed and 23 Maoists were eliminated6. However, there was not much hue and cry by analysts; at least not in the form of pontification insofar as how to combat the five-decade old Left-Wing Extremism [LWE] was concerned. Was it because there were more insurgents eliminated than SFs killed? Was it because the battle of the day was won by the SFs?

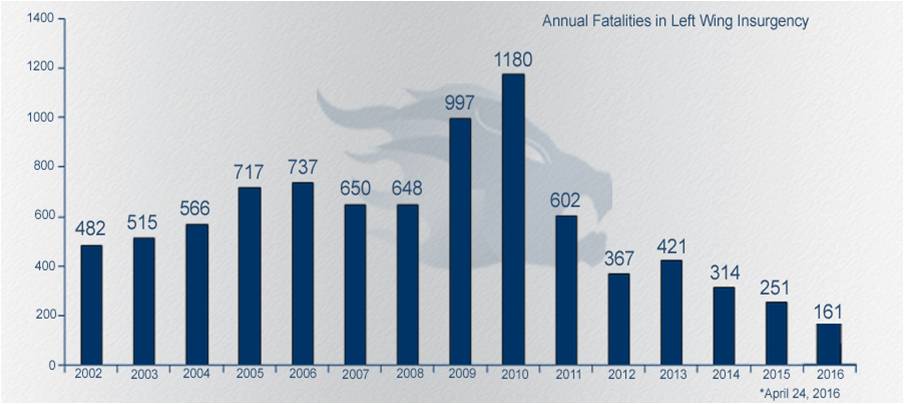

In this backdrop, few pertinent facts need to be looked into. The SFs to Maoists kill ratio remained significantly in favour of the SFs in 2019 at 1:3.84 – the best figure since the year 2000 in Chhattisgarh 7. In 2018, the overall kill ratio was at 1 : 3.16, and the ratio has remained in favour of the SFs since 2011, when it was at 1 : 1.53 8. Nonetheless, in 2010, the SFs to Maoists kill ratio was at 1.01 : 1, favouring the rebels 9. It is clear that the tide of war has steadily turned against the Maoists since 2011. In fact, the annual fatalities are more or less on a declining curve since 2011 as could be seen in the adjoining figure [Courtesy : SATP].

There was a peak of fatalities recorded in 2010 – the very year in which 76 SFs were gunned down by the ultras in Chhattisgarh on 6th April 10. But the total number of fatalities has shown a declining trend thereafter and the fatalities recorded in 2017, 2018 and up to 23 June 2019 were 169, 249 and 56 respectively in the state of Chhattisgarh 11. Moreover, the geographical space in which the Maoists operated in 2007 has shrunk by almost 90 percent in 2020 with respect to ‘Highly’affected districts. This is another feather in the cap of the SFs as well a validation of the policy adopted to negotiate LWE. In September 2007, there were 62 highly affected districts 12 in the country, whereas the number has gone down to a mere four in 2020 13.

From the data it is evident that the insurgency is under control by the SFs – even in Chhattisgarh – the core region of dominance of the Maoists. However, with about 8,000 fatalities from 2005 to 2019 (SATP), this is indeed still a serious insurgency being waged in certain localized pockets of India 14. In 2018, the US Country Report on Terrorism ranked the Communist Party of India – Maoist (hereafter CPI-M) as the deadliest terror organisation globally after the Taliban, Islamic State, Al-Shabaab, Boko Haram and the Communist Party of the Philippines 15.

Rather interestingly, the Maoists have reportedly proposed to talk with the government as recently as in March 202116, but ironically followed it up with two consecutive ambushes/attacks on the SFs. The first one was a landmine explosion on 23rdof March 17 and the next on 3rd April 18. Moreover, the ultras have expressed displeasure at the choice of the convenor of the peace process as well as put forth, among other things, the preposterous demand of dismantling the camps of the armed forces from the region and lift the ban on the CPI-M as pre-conditions for talks 19.

In this scenario, few questions definitely need to be addressed:-

- Does the event of 3rd April 2021 indicate a resurgence of the Maoists in India?

- Is the present counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine that is being carried out by the SFs, flawed?

- Will talks with the Maoists be a fruitful venture to quell violence in the region and usher in long term development?

- How to end this five-decade old insurgency?

Very Brief Backgrounder

Before these questions are dealt with one by one, there is no harm to briefly delineate the reasons for the demise of the erstwhile Naxalite insurgency in its first phase of 1967 to 1972. Weak organization of the party, lack of mass mobilization, indiscriminate use of violence in which police officials of the subaltern ranks were butchered by the insurgents for no just cause and of course tactical torture of the Naxalites (aka Maoists)by the police as well as cadres of then mainstream political parties. Nonetheless, the most important reason for the decapitation of the insurgency in its first phase was the alienation of the Naxalites from the masses in general and unnecessary reliance on the theoretical premise of ‘annihilation of the class enemy’ of their ideologue Charu Mazumdar.

Mazumdar died (with his chimera of a ‘revolution’) in police custody in Calcutta in July 1972, yet the movement somehow failed to die. Between 1972 and 1985 the Naxalite movement branched out to other provinces of India, specifically Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand. People’s War Group [PWG] was formed in Andhra Pradesh and the Maoist Communist Centre [MCC] in Bihar-Jharkhand region. After a series of internecine skirmishes, gory bloodletting and ideological tussles, finally in 2004, the PWG merged with the MCC under the banner of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. The idea was to have a vanguard revolutionary party [Leninism] which would essay to usher in a New Democratic Revolution [NDR] in India by toppling the so-called ‘bourgeois government’. The process of ‘toppling’ would be carried out through political, social, economic and most importantly military means. The first phase of the military action would be spearheaded by a People’s Liberation Guerilla Army [PLGA]. From 2004 onward, the Naxalites officially began to be called as Maoists [because of their strict adherence to guerilla warfare tactics] and the movement turned more organized, hierarchical and militarized. Ganapathy became the General Secretary of the CPI-M from October 2004. From Central Committee to Squad/Area committees, through state and district formations, the Maoist party maintained its rigid hierarchy.

Foreign Arms & Weapons?

The 3rd April 2021 ambush by the Maoists was a copybook case of V-Ambush coupled with Demolition Ambush 20. In the latter, explosives are used and a smaller force plans to wipe out a comparatively larger force. Good intelligence on the route taken by the SFs was thus required; which was presumably available with the insurgents, who had a comparatively smaller contingent (400 militants) to about 1000 SFs to combat with. Reportedly, light machine guns, explosives and under barrel grenade launchers were available with the Maoists 21.

However, sophistication and variety of weapons used by the insurgents is nothing new. If the weapons used on 3rd April were supposedly stolen from the SFs in earlier conflicts, it was rifle with a 'Made in Germany' mark that was recovered from the insurgents on May 2, 2018 22. A sub-machine gun of the US make was seized from the Maoists on July 4, 2018 23. A Maoist spokesperson had revealed during his interrogation that they had bought arms and ammunition from abroad till 2011 25. In June 2019, Chhattisgarh police had recovered Heckler and Koch G3 Rifle from the Maoists 26–a small arms’ variety used by NATO and Pakistan Army.

This should not turn out to be a surprise though. The Maoist supply lines for weapons are two-fold. First, from the SFs, when on occasions the ultras gain an upper hand in any tactical counter offensive campaign [TCOC] generally launched in the summer months of March to June. Second, is from the trail of smuggling through India’s North-East and into the Dandakaranya region (Maoist base area in central India) via the provinces of West Bengal or Odisha.

Apart from guns and explosives, the Indian Maoists have had a symbiotic relationship with the Maoists of Nepal and Philippines, as well as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) of Sri Lanka – insofar as training is concerned. Furthermore, in late 2018, Ganapathy relinquished his position as Maoist General Secretary due to ill health, and was suspected to have fled to the Philippines. He supposedly escaped to Nepal and then fled to the Philippines from there. However there has been no confirmation by the Indian Maoists to this effect 27.

Even India’s Minister of State for Home Affairs said that Indian Maoists were receiving support from European organisations 28. He also said that “the CPI-Maoist clandestinely getting foreign funds cannot be ruled out. Inputs also indicate that some senior cadres of the Communist Party of the Philippines imparted training to cadres of the CPI-Maoist in 2005 and 2011” 29.

Nonetheless, from the security perspective, the Indian Maoists are in the strategic defence phase of guerrilla warfare and very likely would continue to do so with more focus on low-end technology like Improvised Explosive Devices [IEDs]. They would attempt to repeat more often events like that of 3rd April in order to gain media attention and consequent advantage in psychological operations against the SFs; so as to dent the morale of the rank and file of the SFs and also spread disinformation of alleged atrocities committed by the SFs. The insurgents want to win over the local populace and simultaneously carry out Black Operations against the SFs. These are tactics without ethics, well and truly imbibed by ruthless insurgents whose backs are against the wall. Their kernel is gradually shrinking in size and the ultras know it very well. A chunk of the national media highlighting the death of the SFs on 3rd April and downplaying the elimination of the Maoists are doing no good to the overall counterinsurgency (COIN) approach either.

As a form of natural reaction to the constant pressure created by the SFs in their strongholds, it was expected of the insurgents to enhance militarism by some margin. And this appears more so after the taking over of the Maoist leadership in November 2018 by Nambala Keshav Rao, alias Basavaraju, who has a bachelor’s degree in technology. Emphasis on IEDs, ambushes, booby-traps and broader variety of weapons and even drone technology is discernible since his taking over from Ganapathy.

And if a valid question is raised regarding the source of funds for the procurement of weaponry, it may be noted that about $ 20 million USD per year is collected by the CPI-M, and as an analyst writes, “from business houses, contractors, corrupt government officials; and political leaders. The largest and principal sources of income for the Maoists are the mining industry, PWD works, and collection of tendu leaves” 30

India’s COIN Approach

India has mostly refrained from deploying the army in COIN operations against the Maoists. Rather, state police and Central Armed Police Forces [CAPFs] have done the job. However, in Operation Steeplechase in the 1970s – unleashed to decimate the erstwhile Naxalite movement, the services of the Indian army were used. But the army did not play a major role. It provided the outer ring of personnel with the CAPFs and the state police doing the actual operations in the form of concentric rings within the larger ambit of the army. In May 2017, the then Union Home Minister announced a new strategy against the Maoists, called SAMADHAN (solution). The acronym expanded thus: S: Smart leadership, A: Aggressive strategy, M: Motivation and training, A: Actionable intelligence, D: Dashboard-based KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas), H: Harnessing technology, A: Action Plan for each theatre and N: No access to financing.

Furthermore, Rajagopalan (2009) writes: “…the Indian experience with insurgencies is worth serious study and perhaps emulation. India has not only managed to keep under control a large number of rebellions, but has managed to do so without recourse to the kind of methods that has recently been referred to as the ‘strategy of barbarism’….”31. Also, the Indian Army’s doctrine on sub-conventional warfare published in December 2006 stresses on the following 32:

“Winning of the hearts and minds [WHAM] of the populace is paramount to the success of sub-conventional operations and should be undertaken… This reiterates the importance of people-friendly operations. Role of Security Forces is to suppress the violence and create conditions for the State to build capacity for peace building”

India is mostly concerned with three major insurgencies, viz., in the North-East, Kashmir, and the Left-Wing Extremism [LWE]. The three cases have different historical, cultural, and political undertones. India has dealt with these keeping in mind their regional and ethnic specificities, within the overall ambit of the rule of law. Against the Maoists however, a combination of classical and ‘quantum’ COIN holds the key. The essential elements of such a COIN are:

- Winning Hearts and Minds of the ambient population (classical COIN)

- Decapitate the top leadership of the Maoists (quantum or targeted COIN)

- Cost-effective anti-IED techniques to be incorporated.

- Standard Operating Procedures [SOPs] need to be followed at all levels to avoid ambushes and also to set up ambushes for the insurgents. That is, to give them a taste of their own medicine.

- SFs to induct local people like that in Bastariya battalion in Chhattisgarh. Knowledge of local terrain along with viable ground level intelligence would go a long way to win the low-intensity conflict.

- To infiltrate the ranks of the insurgents, i.e. efficient system of espionage.

- To create schisms in the CPI-M, at all levels.

- Allure the foot soldier with lucrative job and/or surrender policy. This is already in vogue, but could be always made more attractive financially.

- Knowledge of local language by the SFs. Chhattisgarh state police has started working on this mechanism.

- Effective PR management by the SFs, which can include Black operations against the insurgents as well.

Along with these two prime aspects, the following are essential components:

Can the Maoists Defeat the SFs?

A simple calculation will set things straight. As of 03rd December 2019, the Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs) had an actual strength close to 9,00,000 personnel 33. On the other hand, the strength of Maoist guerrilla army varies between 10,000 to 15,000 cadres and about 50,000 members of associated wings and militia.Leaving aside the state police forces [which are about 2 million], the CAPFs have advantage of around 9:1 personnel ratio vis-à-vis the Maoists.

In addition, the modernization, training and professional level of the CAPFs and also the state police keep them at a much higher pedestal compared to the insurgents, who have still been unable to graduate to the next level of ‘strategic stalemate’ in guerrilla warfare, and that too in a span of over 50 years since the commencement of the insurgency.

Nevertheless, it has been opined that insurgencies generally end not through military action but due to social, economic, and political change 34. Moreover, a veteran Indian army officer opines that the Maoist insurgency would meet its death when the people would believe that the government is reasonably effective to address their grievances within a suitable time frame 35. Empirical results indicate 36 that the conflict is most likely in districts where local grievances along with economic conditions make the organisation of a rebellion feasible. The study also tells that effective implementation of development programmes by the Government of India – especially the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act [MGNREGA] is related to immediate suppression of violent activities in Maoist-affected districts.

In this context, it is noteworthy to mention that the Indian government has gone for specific measures to combat LWE 37 which have turned out to be efficacious:

Security Related Expenditure (SRE) scheme:

- The Government of India reimburses the LWE affected state governments the security related expenditure incurred on ex-gratia payment to the family of civilian/security forces killed in LWE violence, training and operational needs of security forces, insurance of police personnel, compensation to the surrendered Left Wing Extremist cadres, community policing, village defence committees and publicity material.

- Fortified police stations have been constructed in the LWE affected states

- ‘Skill Development in 47 LWE affected districts’ and ‘Pradhan Mantri [Prime Minister’s] Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY)’ for creating infrastructure and providing employment linked skill training to youths in LWE affected areas.

Moreover, under provision of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, 1,543,656 title deeds have been distributed to the individuals and communities to ensure their livelihood and food security and protect their rights on the forest land in 10 LWE affected States [MHA Annual Report].

Talks with the Extremists?

In the wake of the 3rd April attack and in general, few analysts have opined that India should follow the example of Colombia and Nepal and resolve the five-decade old insurgency by talking to the ultras. However, they fail to recognize that the situations in Colombia as well as Nepal were rather dissimilar to that in India. The Colombian insurgency had taken a much heavier toll of lives vis-à-vis that in India. But that is not the only reason to paint the Colombian structure with a different colour. The point which is missed by the pro-talk analysts is that the Norwegians were mediating in the Colombian case and the matter had received considerable international attention. Moreover, the peace deal with the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) insurgents is yet to be termed as fully successful because even after the giving up of arms by the rebels and their consequent rehabilitation, conflicts with former FARC rebels grab headlines of late 3839. Colombian peace process remains a fragile case.

As far as Nepal is concerned, the negotiations were agreed upon by the then monarchy not just due to the military successes of the Maoists – which were not really decisive with the Nepalese army pitching in with sturdy retaliation – it was more so because of countrywide anti-monarchy protests launched by political parties, and joined by the Maoists. The Nepalese Maoists in fact grabbed the opportunity of ‘peace’ as a tactical measure to get into the power structure. At the other end, India is a democracy, with a shrinking geographical and ideological space for the Maoists. And with the Maoists having failed to garner any tactical alliance with other left-wing political parties, let alone centrist parties, the threat posed by the insurgents is locally confined to certain pockets – especially in Dandakaranya, which borders Chhattisgarh with the states of Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Maharashtra. Even militarily, the threat is not at all formidable considering the lack of progress made by the Maoists in the organizational sphere.

Moreover, it would be worthwhile to recollect that talks failed twice with the Maoists – once in 2004 in Andhra, which ultimately paved the way for the formation of the CPI-M; and again in West Bengal, after the Lalgarh fiasco in 2009-10. If at all talks have to take place with the insurgent group, it is recommended to talk from a position of strength. Daniel Byman asserts that “Talks with insurgents are politically costly, usually fail, and can often backfire” 40.

Without however citing standard examples of India’s successes in COIN operations in Kashmir and overall in the north-east, it would be rather pragmatic to illustrate the case of the state of Tripura. There were ‘636 police personnel per 100,000 people in Tripura,’ a figure far greater than the national average of 141 41. To defeat the insurgents, the Tripura police came out with a ‘concept and conduct of COIN operations’ in August 2000 and formed Quick Reaction Teams at each company-level operation base. Small-unit operations by the Tripura police turned out to be hugely effective 42. Similar operational paradigm was also successful in Sri Lanka in the Eelam War IV 43. Specialised training for COIN operations, enhanced capacity for intelligence gathering, modernization of the police force and strictly adhering to Standard Operating Procedures, among other factors, made the Tripura police COIN operations successful 44.

In this backdrop, the following are suggested:

- Every Maoist-affected state ought to raise Special Forces (trained in COIN operations). The Greyhounds of Andhra Pradesh can serve as a paradigm.

- In addition to the Special Forces specifically dedicated toward anti-Maoist operations, a sizable chunk of the state police forces (of Maoist affected states) must also be trained in COIN operations for a period of 1 to 2 years.

- More COIN-schools are to be raised in the Maoist affected states. Every affected state must have at least two COIN warfare schools. Services of expert faculty members/trainers from the Indian Army, para-military, Central Armed Police Force (CAPF) and state police need to be utilized.

- The integrated command structure under MHA as the nodal authority needs to continue and strengthened. Every Maoist affected state must be made to realise the urgency to cooperate with MHA in COIN strategy and operations, irrespective of its political affiliation.

- Intelligence sharing among states needs to be effected in letter and spirit. This is significant since the insurgents hop from one state to another through the jungles and rough terrain.

- Every Maoist affected state to earmark funds for COIN operations, in addition to the funding being received from MHA. In fact, the Government of India has done appreciable work in this sphere 45. The state governments need to align accordingly.

- During any anti-Maoist operation, the state police contingent needs to be equitably distributed alongside the CAPFs. In fact, joint training of the CAPFs and state police forces could be commenced for instilling better camaraderie and synergy.

- The largest chunk of weapons accessible to the rebels is home-made and of low-technology. In order to stem this flow of weapons, the rebels need to be continuously monitored, their base areas searched and combed and overall Control-Hold-Build doctrine of the COIN needs to be effected.

- However, access to explosives and ammunition from external sources could be denied through proper intelligence and coordination. Only a thorough synergy among the different security agencies can help the SFs track the connection between the rebels with:

- Arms smugglers within and without Indian borders

- North-East Insurgents

- Trans-national terrorists

Any such connection needs to be monitored through multi-agency tracking and nipped in the bud. National Investigation Agency (NIA) and state-based Special Task Forces (STFs) have done commendable work on this. They need to continue doing so, but further fillip is required with credible ground intelligence inputs.

Penetration into Maoist base area

At present, the fundamental base of the Maoists is in the territorially inaccessible forests of Abujhmaad, in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh. To physically capture Abujhmaad, a holistic combination of the following is required:

- UAVs/Drones/satellite imagery to be used for tracking down the Maoist presence in the jungles

- District/Area level police forces should be inducted from the local population/ethnicities. More recruitment needs to be effected. In Sri Lanka in Eelam War IV and in Tripura COIN war, there was a definite surge in recruitment. As Kumar opines 46, “…the shortage of troops cannot be compensated through firepower, technology…” and “deployment of local forces is especially helpful in COIN due to their better cultural and situational awareness.”

- Division among insurgent ranks is essential since that would deplete their strengths as well as leave them in disarray. This method was successfully implemented in Sri Lanka 47 when Col Karuna defected from the LTTE.

- Air power can be used not only for supply of logistics but also in offensive mode to reduce troop casualty and to effect faster troop movement and targeted elimination of the insurgents.

Along with Abujhmaad, multiple streams of forces can be unleashed simultaneously in other Maoist zones. In fact, the operations can be worked out in major Maoist affected districts in a manner that the rebels do not get a breather and their supply lines are jeopardized. This amount of targeted and comprehensive attack will eventually wipe out the rebels’ structure on the ground.

Returning to the Questions Raised

- The 3rd April 2021 event was an unfortunate loss for the SFs, no doubt. But that was an aberration in the overall declining trend of Maoist activities in India as well as in Chhattisgarh. These events are routine within the ambit of TCOC. On most days the SFs win, on very few days, the Maoists have lesser casualties. 3rd April was one such day.

- The present COIN doctrine followed by the SFs is quite successful in its application. However, there are always gaps to be plugged in and there is no harm if on a periodic basis any chink in the armoury is rechecked. The 3rd April attack could be interpreted as a wakeup call for the SFs insofar as tactical implementation of the COIN doctrine is concerned. There are no reasons to sound alarm bells and start blaming the top brass of the SFs for the apparent failure.

- Will the Maoists give up arms and sit at the negotiating table? Rather unlikely, and more so considering the pre-conditions put forth by the extremists for the talks. The group whose sole ambition is to usher in an NDR by eradicating the bourgeoisie democracy, will hardly agree to talk and give up arms, either post-talk or pre-talk. If they shun arms, they lose their identity which they can hardly afford. Talking, for the Maoists, is to gain time and regroup and reinvigorate. At a position of strategic advantage, the SFs could ill afford to squander the opportunity and provide the ‘advantage of time’ to the Maoists.

- The insurgency wouldn’t end suddenly, not on one fine morning or evening, with any individual claiming the Nobel peace prize as happened in Colombia. Its military intensity would gradually diminish as the SFs persistently pursue the COIN philosophy in a steadfast manner. As the government implements its pro-people schemes and constitutional provisions for the tribal populace, the Maoist ultras would lose the sea of people, to swim their way, and automatically be exposed to the SFs to be eliminated easily. As development reaches the nook and corner of the affected regions, along with the security structure forcing the insurgents in cocoons of ever shrinking radii, the insurgency would be less than ragtag. The present efforts verily indicate that endgame.

References

- : UPA to NDA, India still confused on how to fight Naxal insurgency. Maoists know that

SHEKHAR GUPTA, The Print, 4 April, 2021, https://theprint.in/opinion/upa-to-nda-india-still-confused-how-to-fight-naxal-insurgency/633962/ - : We are winning against Maoists, but it doesn’t have to come at such high cost

April 11, 2021, Rahul Pandita in Voices, India, TOI, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/voices/we-are-winning-against-maoists-but-it-doesnt-have-to-come-at-such-high-cost/ - : India’s Maoist strategy needs a reset. But will Modi govt change its muscular approach?

NIRANJAN SAHOO , The Print, 8 April, 2021 - : Re-calibrating Strategies to Combat Maoists’ Violence, Lt. Gen (Dr) Vijay Kumar Ahluwalia, April 07, 2021, https://www.vifindia.org/article/2021/april/07/re-calibrating-strategies-to-combat-maoists-violence

- : Chhattisgarh Maoist attack: India’s left is also complicit in the murder of 22 soldiers

April 6, 2021, Rahul Shivshankar in Beyond The Headline, TOI - : 23 Maoists were killed in Minpa encounter which took place in March: Bastar Police, Hindustan Times, Ritesh Mishra, Edited by SparshitaSaxena, UPDATED ON SEP 12, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/23-maoists-were-killed-in-minpa-encounter-which-took-place-in-march-bastar-police/story-zwedqUEqJPIqRKppIj0oCL.html

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal, Chhattisgarh: Assessment- 2021, https://www.satp.org/terrorism-assessment/india-maoistinsurgency-chhattisgarh#:~:text=Moreover%2C%20while%20the%20SF%20%3A%20Maoist,to%201%3A1.89%20in%202020.

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal, Maoist Insurgency: Assessment- 2021, https://satp.org/terrorism-assessment/india-maoistinsurgency#:~:text=A%20high%20of%20628%20civilian%20fatalities%20were%20recorded%20in%202010.&text=The%20SF%3AMaoist%20kill%20ratio,in%202019%20at%201%3A3.14.&text=Since%20March%206%2C%202000%2C%20the,addition%20to%20776%20in%202018.

- : ibid

- : The Bad War, Uddipan Mukherjee, Newline, April 2010, https://newslinemagazine.com/magazine/the-bad-war/

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal, Maoist Data Sheet, https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/data_sheets/Fatality_Chhattisgarh.htm

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal Conflict Map 1, https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/database/conflictmap.htm

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal Conflict Map 2: https://www.satp.org/conflict-maps/india-maoistinsurgency

- : South Asia Terrorism Portal, Fatalities in Left-wing Extremism: 2005-2019

- : Communist Party of India (Maoist) sixth most dangerous terrorist organisation in the world: US report, WION Web Team, New Delhi, Delhi, India Published: Nov 06, 2019, https://www.wionews.com/india-news/communist-party-of-india-maoist-sixth-most-dangerous-terrorist-organisation-in-the-world-us-report-260393

- : Chhattisgarh: Maoists make ‘conditional offer’ for peace talks, seek removal of armed forces, Sravani Sarkar, March 17, 2021, https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2021/03/17/chhattisgarh-maoists-make-conditional-offer-for-peace-talks-seek-removal-of-armed-forces.html

- : Three security personnel killed, many hurt in Maoist attack in Chhattisgarh, TimesofIndia.com, March 23, 2021,

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/three-jawans-killed-in-naxal-attack-in-chhattisgarh/articleshow/81652451.cms - : Indian forces step up operations against Maoists after 22 police killed in ambush, Jatindra Dash, Rupam Jain, Reuters, April 5, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/india-maoist-attacks-idUSKBN2BS0QX

- : Please see reference 16

- : The Counterinsurgency Manual, Leroy Thompson, pp 136-137, KW Publishers Pvt Ltd, New Delhi, 2010

- : Rescue chopper landed late, says survived cop, 07 April 2021, The Pioneer, https://www.dailypioneer.com/2021/state-editions/rescue-chopper-landed-late--says-survived-cop.html

- : C'garh cops probe source of foreign arms seized from Maoists,

Press Trust of India, July 29, 2018

https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/c-garh-cops-probe-source-of-foreign-arms-seized-from-maoists-118072900092_1.html#:~:text=A%20rifle%20with%20a%20'Made,4%2C%20a%20police%20official%20said. - : Chhattisgarh cops probe source of foreign arms seized from Maoists, DT Next, Jul 29,2018, https://www.dtnext.in/News/TopNews/2018/07/29112858/1081899/Chhattisgarh-cops-probe-source-of-foreign-arms-seized-.vpf

- : C'garh cops probe source of foreign arms seized from Maoists

Press Trust of India, July 29, 2018

https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/c-garh-cops-probe-source-of-foreign-arms-seized-from-maoists-118072900092_1.html - : Ibid

- : Chhattisgarh: High-Tech Heckler And Koch G3 Rifle Used By Pakistani Army, NATO Recovered From Maoists, Swarajya Staff, Jun 15, 2019,

https://swarajyamag.com/insta/chhattisgarh-high-tech-heckler-and-koch-g3-rifle-used-by-pakistani-army-nato-recovered-from-maoists - : Maoist boss Ganapathy may have fled to Philippines, DECCAN CHRONICLE, RABINDRA NATH CHOUDHURY, Dec 1, 2018, https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/011218/maoist-boss-ganapathy-may-have-fled-to-philippines.html

- : Maoists getting support from European organisations, home ministry says

Aman Sharma, ET Bureau, Jul 15, 2014

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/maoists-getting-support-from-european-organisations-home-ministry-says/articleshow/38419095.cms - : Some Maoist cadres got training from Communist Party of Philippines

Press Trust of India, New Delhi, Last Updated on July 15, 2014,

https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/some-maoist-cadres-got-training-from-communist-party-of-114071500861_1.html - : P.V. Ramana (2018): Maoist Finances, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2, April-June 2018, pp. 59-75

- : https://www.india-seminar.com/2009/599/599_rajesh_rajagopalan.htm

- : https://indianstrategicknowledgeonline.com/web/doctrine%20sub%20conv%20w.pdf

- : https://www.mha.gov.in/MHA1/Par2017/pdfs/par2019-pdfs/ls-03122019/2303.pdf

- : https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2010/RAND_MG965.pdf

- : https://idsa.in/event/FutureoftheNaxaliteMovement

- :https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2233865912447022

- : MHA Annual Report, 2018-19

- : Colombia’s fragile peace deal threatened by the return of mass killings

February 16, 2021, Camilo Tamayo Gomez, The Conversation.com, https://theconversation.com/colombias-fragile-peace-deal-threatened-by-the-return-of-mass-killings-154315 - : Killings of Colombia ex-FARC fighters persist amid peace process, Al Jazeera, Steven Grattan, 18 Jan 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/1/18/killings-of-colombia-ex-farc-fighters-persist-amid-peace-process

- : Byman, D. (2009, April). “Talking with Insurgents: A Guide for the Perplexed”, The Washington Quarterly, April 2009, pp. 125 – 137

- : Kumar, K. (2016). “Police and Counterinsurgency: The Untold Story of Tripura’s COIN Campaign”, Sage, ISBN 978-93-515-0747-5 (HB)

- : ibid

- : Hashim, A. S. (2013). “When Counterinsurgency Wins, Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers”, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-93-82993-47-6

- : See Reference 41

- : PIB Delhi. (2019, July 17). “Steady decline in casualties in Naxal attacks”, PIB Delhi, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1579194

- : See Reference 41

- : See Reference 43

https://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/data_sheets/fatalitiesnaxal05-11.htm

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/zbKZfHMbh_EJ59..UhF3NQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTU0MDtjZj13ZWJw/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/f9OmbRC6nlD6z7qgSP.ayw--~B/aD04MTA7dz0xNDQwO2FwcGlkPXl0YWNoeW9u/https://media.zenfs.com/en/newsbytes_319/ba4564fe39c8acc028e08700c4e2b8af

Post new comment