As the Indian External Affairs Ministry prepares for the BRICS Foreign Minister’s Meeting, Beijing has proposed to set up an Innovation Base to strengthen the grouping’s cooperation on 5G, digital economy, Artificial Intelligence, information technology, and other new technologies. The base, as proposed by the Chinese Information and Industry Minister, would be based out of China. The proposal comes at a time when India and China are engaged diplomatically to de-escalate the hostilities on the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom (U.K.) has intensified the efforts to expand the Group of 7 (G7) and convert it into a Democratic Alliance of ten countries (D-10). The U.K. exclusively wants the group to talk about 5G and viable supply chains. The U.K. wants India to be a part of the D-10. The proposal by China and the proposed expansion of the G7 comes at a time when UK-China relations are getting worse, mainly due to the recent wide-ranging new security law imposed by China in Hong Kong. Both proposals pose two vital questions for India. The first question being, why has China proposed to set up the innovations base? Furthermore, what opportunities India can explore if it agrees to one of the proposals?

Scrutinizing China’s Motives

The proposal by China to set up a BRICS innovation base seems to be a play towards consolidating the Global South Markets. BRICS, as conceptualised by Jim O’ Nell, an economist with Goldman Sachs in 2001, saw the grouping then (minus South Africa) as an intersection for South-South Cooperation. BRICS was expected to create an alternative model to the western led security paradigm. Unfortunately, China’s aggressive tactics in the South China Sea, along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India, and creating debt traps through the Belt and Road Initiative, along with the new security law in Hong Kong, have dampened China and, in extension, BRICS role to be a viable alternative.1

The aftermath of the border clashes saw India also banning 59 Chinese apps and putting 250 more on notice to monitor if they violate user privacy and national security. The apps ban dubbed as a “digital strike” by the Indian media has seemingly set a precedent for countries like the U.S to show an inclination towards taking similar steps.2 President Trump issued an executive order which bars U.S firms from doing business with significant apps like TikTok, WeChat, and others. The executive order, as explained by Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo in a press briefing, was that the parent companies of the Chinese apps that are based out of China pose a threat to personal data of American citizens. The Indian government, too, gave a similar explanation. Japan is taking similar steps in the same direction. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party wants to ban the Chinese apps by “taking legislative steps.”3

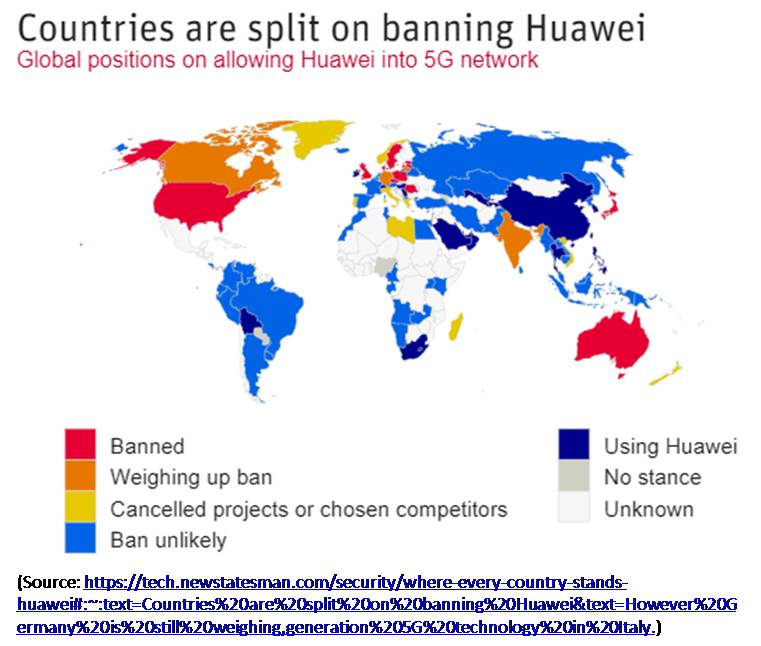

In a similar vein, the U.S has been persistent on the world stage to ban Huawei and not allow it to enter the telecom sector of different countries. The U.S. government and Huawei are engaged in lobbying efforts worldwide. The U.K. government has taken concrete steps to effectively curb Huawei’s role in the country’s future 5G plans. The worldwide condemnation of Huawei by the U.S has not been sufficient thus far as allies and friends barring a few have allowed Huawei’s participation. The majority in Central Asia, South America, and Africa will not rollback the 5G technology deployed by Huawei.4 The largely unsuccessful attempts by the Trump administration to ban Huawei worldwide might not have worked, but it has choked their revenue streams. The U.K., as mentioned before, has banned their involvement in the future with other European countries, thus the future of one of China’s largest tech companies, especially in broader markets, and is under threat.

The Indian government, as it weighs in more towards banning Huawei, has led to a loss of revenue to Huawei. The tech giant has slashed its revenue target by 50 per cent from India. They also laid off 60-70 per cent of the staff in India barring those in Research and Development and the Global Service Centre. Severe steps by Huawei could be due to two of India’s three major telcos are looking more towards the competition, namely Samsung, Ericsson, and Nokia. The Chinese tech giant is not expecting any new business from India in the future. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest contract semiconductor maker, has stopped taking orders from Huawei to comply with the new U.S. export controls putting in question the supply chain for the Indian telcos.5

The loss of business for Huawei and ZTE in the Indian market has put a question mark on the future of Chinese companies. The idea for an innovation base by the Chinese during the BRICS Industry meeting could be a face-saving effort to inspire confidence in the Indian consumer. The idea behind this proposal seems to be inspired by the British plans to include India into its G7 expansion plans to discuss similar issues.6

Should India Consider the BRICS Proposal?

To answer this question, it is imperative to understand what the role of an innovation base is? Simply put, it is a stockpile of ideas, discoveries, and inventions that help in innovation efforts towards creating a sustainable competitive advantage. The base acts as a strategic reserve, which determines the future actions and performance and is a vital resource pool. Setting up an innovation base would add to the existing formidable scale considering the reach of its tech companies, data sets, scientists, and engineers along with venture capital.7

The Chinese proposal seems to have followed the U.K. G7 expansion plan in spirit. Meanwhile, in the U.S. calls for creating an “alliance innovation base” is gaining traction. Technological advances in the 21st century will not only help in economic prosperity but give a tremendous advantage to the military. Having a better reach and influence in world affairs in the future would be determined by who ascends new technological heights first. 8 The proposal put forth other members of the BRICS and, if accepted, would precede the U.S. administration’s thinking on setting up an innovation base. There is already disagreement on expansion plans between the U.K. and U.S., as the latter wants to include Russia into the grouping. The U.S. has not clarified the agenda of the meeting, unlike the U.K., who are determined to make the D-10 into an “Anti-China” alliance to discuss 5G and supply chains. India early June 2020 got an invitation to join the G7, which was scheduled to be held in Washington D.C but postponed due to COVID-19.

Other members of the BRICS have accepted the Chinese tech companies. Russia is cooperating closely with the Chinese, especially Huawei, to set up their 5G infrastructure. In South Africa, three of its major telecom companies are using Huawei’s equipment, and in Brazil, Huawei is a part of 5G trials. The recent escalation of the border conflict on the LAC has put a question mark on Chinese involvement in the telecom sector in India. The Indian government has already started taking steps to not only contain but curb Chinese investments in critical sectors of the economy. Huawei’s involvement in India looks bleak.

Conclusion

It should not come as a surprise if India chooses not to accept the proposal. India’s stance against increasing Chinese influence through aggressive tactics was evident in the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where it sided with the U.S. to oppose the expansion of Special Drawing Rights, which has been perceived as going against the demands to reform Bretton Woods’ institutions. BRICS’ track record in COVID-19 has been disappointing as the New Development Bank (NDB) was not able to extend any assistance to developing countries. IMF and World Bank stepped in and provided financial assistance to the developing countries. The failure of NDB reflects poorly on BRICS attempts to create an alternative model and stake its claim as a leading multilateral grouping representing the Global South.9

The path ahead, irrespective of whether the proposal goes ahead for the innovation base, is difficult for BRICS. The grouping’s capability is already stretched thin due to COVID-19, U.S. withdrawal from major multilateral institutions, along with China’s sabre-rattling on the LAC. China’s “Wolf-Warrior” diplomacy and mask diplomacy have, in fact, alienated countries, which until recently advocated for China’s and, in extension, BRICS growing role in global affairs. The imposition of National Security Law in Hong Kong along with intimidating tactics in the South China Sea should be the issues on which India now releases press statements on, condemning these actions. The Chinese authorities today, unlike the ones in the previous decade, are not willing to bide its time. New age Chinese nationalism and the aggressiveness associated with it will last for a while, which in turn might lead to a lukewarm reaction towards the Innovation base proposal, which has been floated.

As a founding member of the BRICS, India’s reaction would be monitored closely by the west and co-members of BRICS. A negative reaction by India towards the Chinese proposal would definitively end the expectation from the grouping to create an alternative to western security paradigms. However, it is a cost that India has to bear due to Chinese aggressiveness and indicate that the government is preparing for the selective competition with China.

References

- Mohanty, Aayush. "COVID-19 Exposes Deficiencies of BRICS." Economic Times Blog. April 06, 2020. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/covid-19-exposes-deficiencies-of-brics/.

- Mohanty, Aayush. "India Starts to Curb Chinese Investments in Digital and Public Sector." The Diplomatist. August 18, 2020. https://diplomatist.com/2020/08/18/india-starts-to-curb-chinese-investments-in-digital-and-public-sector/

- Banerjee, Prasid. "Now, Japan Is considering a Ban on Chinese Apps." Livemint. July 29, 2020. https://www.livemint.com/technology/tech-news/now-japan-is-considering-a-ban-on-chinese-apps-11596002929772.html

- Michael Goodier. "The Definitive List of Where Every Country Stands on Huawei." NS Tech. July 29, 2020. https://tech.newstatesman.com/security/where-every-country-stands-huawei#:~:text=Countries are split on banning Huawei&text=However Germany is still weighing,generation 5G technology in Italy

- Khan, Danish. "Falling Telecom Business Triggers Layoffs at Huawei India; Company Slashes Revenue Target for 2020 - ET Telecom." ETTelecom.com. July 26, 2020. https://telecom.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/falling-telecom-business-triggers-layoffs-at-huawei-india-company-slashes-revenue-target-for-2020/77183960

- Mohanty, Aayush. "Two Expansions: Which G7 Should India Choose?" Vivekananda International Foundation. July 02, 2020. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2020/july/02/two-expansions-which-g7-should-india-choose.

- Mishra, Saurabh, and Rebecca J. Slotegraaf. "Building an Innovation Base: Exploring the Role of Acquisition Behavior." Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41, no. 6 (2013): 705-21. doi:10.1007/s11747-013-0329-6.

- Kliman, Daniel, Ben Fitzgerald, Kristine Lee, and Joshua Fitt. "Forging an Alliance Innovation Base." Center for a New American Security. March 29, 2020. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/forging-an-alliance-innovation-base.

- Mishra, Rahul, and Raj Kumar Sharma. "Taking down BRICS." The Indian Express. June 30, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/taking-down-brics-64836

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2017/12/23/23/14/flag-3036169_960_720.jpg

Post new comment