Background

Chinese interest in Central Asia is multifold. Firstly to secure its northwestern region of Xinjiang, which shares a direct border with three Central Asian countries; Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Xinjiang is home to Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic minority group that has ethno-cultural linkages with Central Asia. Since the creation of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), Uyghurs have consistently faced state repression, which led to an anti-Chinese movement. China feared that they could get support from their Central Asian brethren, which compelled it to craft a partly persuasive and partly coercive Central Asia Policy based on economic dominance. During the Soviet period, Sino-Soviet rivalry had thwarted China's aspirations to make inroads into Central Asia. However, Soviet disintegration led to a gradual Chinese penetration in the region.

Secondly, the import of hydrocarbon resources from Central Asia to cater to the demands of its burgeoning industrial and manufacturing sector, China had invested in multiple oil and gas pipelines. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are the major suppliers of oil and gas to China, while Uzbekistan also moderately exports natural gas to Beijing. China also accounts for 70 percent of imports of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan's raw material exports.

In 2013, at the Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan, Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled a part of its One Belt and One Road initiative (OBOR/BRI), the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) connecting East with the West. This initiative has more geopolitical vigour than its developmental component, as claimed by Beijing. Through SREB, China proposed to build several roads, rail and transport corridors, and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Central Asia with Chinese Investments. China Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank (EXIM) of China are the main creditors to Central Asian Projects.

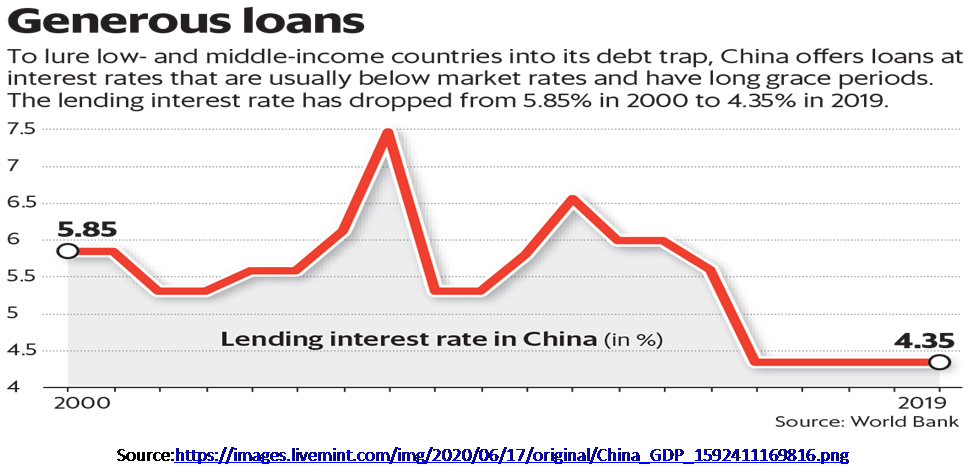

BRI was lauded to revitalize growth and development; however, its sluggish progress reflects a conflicting trend. To make its debt trap score, China uses concessional loans that often come at commercial interest rates and long repayment dates.1 Through the BRI, Chinese state-controlled institutions provide infrastructure funding to low-income economies, which ultimately leaves many with unsustainable debt.2

Today, many countries are on the verge of debt default to China. In 2018, a report by the Center for Global Development highlighted eight BRI recipient countries at a high risk of debt distress due to BRI loans. These countries included Djibouti, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.3 They are highly prone to the mounting debt-to-GDP ratios beyond 50 percent, and around 40 percent of their external debt owed to China.4

Chinese Investments: More Troubles than Benefits

Even after seven years since it was first announced, there is still no shining star project of BRI. Its global outreach seems to be limited and is only restricted to the level of a regional initiative. Many of its detrimental effects of development are visible in the form of the disruption of construction, the destruction of the local environment, the displacement of people, cultural invasion, etc. While Chinese authorities have been justifying the slow progress of the initiate by describing it as a 100-year project, the people of Central Asia don't have that long to wait and have started criticizing such projects. Chinese investment in Central Asia has many problems-

1. Lack of Transparency and Corruption

A high level of corruption and inadequate checks on the Chinese officials generate fewer constraints for China to achieve its policy goals in Central Asia. To protect its companies and encourage investments along the BRI, the Chinese government prefers to rely on closed-door negotiations and financial and political ties with the host countries' leadership. It encourages corrupt practices among the local authorities, which causes concerns for local populations.

2. Predatory Lending and Debt Distress

China is the leading investor in the region, but along with the increase in number of joint projects, Central Asia's debt is also growing. Countries with the export potential to repay their debts to China, such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, are less vulnerable to the Chinese debt trap than remittance dependent economies of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan with lesser exports capacities.

3. Public Resentment

The central Asian population has been suspicious of Chinese ambitions since Soviet times. Chinese investments and related developments have a negligible contribution in raising the living standards of people of Central Asian republics. However, ever-increasing Chinese penetration in Central Asian society has led to anti-Chinese sentiments. This is more prominent in countries like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, which have seen their ethnic brothers tortured in internment camps in Xinjiang.

4. Fear of Cultural Invasion

By offering a lot of money to the local elites, Chinese people have taken over the Central Asian markets, particularly in the bordering areas. There have also been incidents where the Chinese are buying lands in Central Asia and marrying local girls. This has generated a sense of fear of cultural invasion within the local population. Local authorities in bordering areas in Central Asia have often ignored these activities due to the corruption and money being offered by the Chinese people.

How China's Debt Trap works

In order to gain swift political and economic ascendency across the globe, China is dispensing huge sums in the form of concessional loans to developing countries for its large-scale infrastructure projects. It has been witnessed that developing nations are often lured by China's offer of cheap loans for transformative infrastructural projects, which require a considerable investment. These developing countries, mostly low- or middle-income countries, remain incapable of carrying on with the repayments. This provides a golden opportunity for Beijing to demand concessions or advantages in exchange for debt relief.5 This is the pattern of China's debt traps not only in Central Asia but more prominently in South Asia and Africa as well.

Chinese Debt Trap: A Case Study of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

There is a growing concern over the escalating debt owed to China among the general public in Central Asia, mainly in Kyrgyzstan, which has moderate limitations on media freedom. China is accounted for 45.3% of Kyrgyzstan's external debt (May 2019).6 Kyrgyzstan is a relatively developing country with significant BRI-related infrastructure projects being constructed, much of it financed by external debts. By the end of March 2017, publicly guaranteed debt amounted to roughly 65 percent of GDP, of which external debt represented about 90 percent of the total.7

China's Exim Bank is the largest creditor, with reported loans totaling 1.5 billion USD by the end of 2016, or roughly 40 percent of its total external debt.8 Kyrgyz and Chinese authorities are also engaged in discussing the construction of a chain of hydropower plants, a China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, additional highway construction, and the Line D of Central Asia-China gas pipeline, which passes through Kyrgyzstan. While currently considered to be at moderate risk of debt distress, Kyrgyzstan remains vulnerable to shocks resulting from a sizeable exchange rate depreciation exacerbated by the scaling up of public investments.9

According to the report published by the US Center for Global Development in March 2018, the debt figures could amplify as the BRI advances. The report estimated the debt levels of the 68 countries which host BRI-funded projects, taking into consideration their total debt to China as a percentage of total public external debt. The report mentioned that in eight countries, including Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the BRI creates debt sustainability issues if all the planned projects are implemented.10

The economic impact of coronavirus in Kyrgyzstan has been immeasurable. With stressful healthcare management and a steep reduction in remittances, Kyrgyzstan showed its inability to repay Chinese loans. During a meeting jointly summoned by the United Nations (UN) to discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global economy, Kyrgyz President Sooronbay Jeenbekov has pleaded for debt restructuring to allow for more social spending.11 China was also a part of the meeting. It is not clear whether China would grant relief to Kyrgyzstan for debt repayment, but the Deputy Prime Minister of Kyrgyzstan Erkin Asrandiev, without disclosing details, had told that Exim Bank of China has agreed to reschedule debt to Kyrgyzstan. The statement was made based on a conversation held between Kyrgyz and the Chinese President in April 2020.12

Tajikistan owes 1.3 billion USD to the Exim Bank of China, which is 40 percent of the total foreign debt of Tajikistan. Tajikistan's total foreign debt was 2.9 billion USD as of January 2019, according to the finance ministry of the country.13 The first loan that Tajikistan obtained from China was in 2007, and the amount was 217 million USD. Tajikistan's foreign debt to GDP ratio stands at 38.9 percent as of January 2019. The biggest debtors of Tajikistan include the Exim Bank of China, the World Bank, Islamic Development Bank.14

Tajikistan is considered to be a significant part of Chinese BRI in Central Asia. One of the poorest countries in Asia is at a high risk of debt distress, as evaluated by the IMF and the World Bank. Despite being on the radar of Chinese expansionist tendencies, it plans to add to its external debt for arranging payments for its infrastructure investments in the power and transportation sectors. It also includes BRI supported projects. Most significantly, a 3 billion USD portion of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline (Line D) will pass through Tajikistan, reportedly financed through Chinese FDI. The respective stakeholders have not indicated the work and progress of this project. China is the single largest creditor to Dushanbe, and Chinese debt accounts for approximately 80 percent of the real swell in Tajikistan's external debt over the 2007-2016 periods.15

Consequences

Chinese debt has dire consequences for the low-income countries of Central Asia. Chinese companies have acquired mining rights in both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan because of these countries’ inability to repay debts. In Tajikistan, the Chinese Tebian Electric Apparatus Stock Co. Ltd (TBEA) has begun to develop the Upper Kumarg goldfield in the Sughd province. Before this, the company had access to the Duob goldfield, also located in the Sughd province. As per the agreements concluded between both sides, TBEA has the right to extract precious metals from these mines until the Tajik side reimburses the funds spent for constructing the Dushanbe-2 heat and power plant.16

Recently, China's state-controlled media has published articles that made territorial claims in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. These articles mentioned that due to their incapability to repay Chinese loans, countries like Tajikistan had ceded 1100 sq km territory to China in 2011. And it may happen again seeing the rising amount of Chinese debt to these countries. Reports about China having a military base in the Pamir region of Tajikistan suggest another ramification of the debt trap. Chinese malpractices in Central Asia are notably visible. However, the governments of these countries have not taken the issue seriously even after eruption of public outrage against China's perfidy in the region.

References

- Dylan Gerstel, ‘It’s a (Debt) Trap! Managing China-IMF Cooperation across the Belt and Road’ Center for strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/npfp/its-debt-trap-managing-china-imf-cooperation-across-belt-and-road

- Ibid.

- Tim Fernholz, ‘China's "debt trap" is even worse than we thought’, Centre for Global Developmet, 29 June 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/article/chinas-debt-trap-even-worse-we-thought-quartz

- Dylan Gerstel, ‘It’s a (Debt) Trap! Managing China-IMF Cooperation across the Belt and Road’ Center for strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/npfp/its-debt-trap-managing-china-imf-cooperation-across-belt-and-road

- Jhoomar Mehta, ‘China’s growing threat via debt trap diplomacy’, Livemint, 16 September, 2020. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/china-s-growing-threat-via-debt-trap-diplomacy-11592410677912.html

- Daisuke Kitade, ‘Central Asia Undergoing A Remarkable Transformation: Belt And Road Initative And Intra Regional Cooperation’, Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report August 2019. https://www.mitsui.com/mgssi/en/report/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2019/08/27/1908e_kitade_e_1.pdf

- John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance. 2018. “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective.” CGD Policy Paper. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-roadinitiative-policy-perspective

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Kitade Daisuke (2019), “Central Asia Undergoing A Remarkable Transformation: Belt And Road Initiative And Intra Regional Cooperation”, Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report August 2019. https://www.mitsui.com/mgssi/en/report/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2019/08/27/1908e_kitade_e_1.pdf

- Ayzirek Imanaliyeva, ‘Kyrgyzstan: President pleads for sovereign debt restructuring’, Eursianet, May 29, 2020. https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-president-pleads-for-sovereign-debt-restructuring

- ‘Exim Bank of China to reschedule debt of Kyrgyzstan’,

https://24.kg/english/151447_Exim_Bank_of_China_to_reschedule_debt_of_Kyrgyzstan_/ - https://www.asiaplus.tj/en/news/tajikistan/politics/20190611/what-does-tajikistan-expect-from-the-chinese-presidents-state-visit

- Ibid

- John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance (2018), “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective.” CGD Policy Paper. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-roadinitiative-policy-perspective

- Maria Levina, ‘Can Central Asia countries pay their external debts?’, Times of Central Asia, March 17, 2019. https://www.timesca.com/index.php/news/26-opinion-head/20949-can-central-asia-countries-pay-their-external-debts

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://cdni0.trtworld.com/w1140/h490/q75/62360_CHN20190828USATRADECHINATARIFFS_1576142990963.JPG

Post new comment