On 20 April 2020, the incumbent Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Likud Party signed an agreement to form unity government with Benny Gantz’s Kahol Lavan Party ending the yearlong political deadlock and averting the possibility of fourth election. The Israeli political system has been in a state of crisis after Yisrael Beiteinu withdrew support from the Likud led coalition in November 2018 to protest against the ceasefire with Hamas. Consequently, two successive elections held in April and September 2019 failed to facilitate a majority government. Eventually, the third election was held on 2 March 2020. In the backdrop of COVID-19 pandemic, the outcome of the March 2020 election crisis has forced reconciliation. However, mutual distrust is likely to hamper its political functioning.

Ideological Orientation of Key Political Lists in Israel

Likud: Revisionist Zionism, National conservatism; Pro Annexation

Shas: Religious and social conservatism; Sephardi ultra-orthodox oriented; Opposes mandatory conscription

United Torah Judaism (UTJ): Religious and social conservatism; Ashkenazi ultra-orthodox oriented; Opposes mandatory conscription

Yamina: National conservatism; Pro-annexation; Supports settlement in Occupied West Bank

Yisrael Beiteinu: Secularism; Pro-annexation; Supports settlement in Occupied West Bank; Supports mandatory conscription

Labor: Labor Zionism; Secularism; Pro-two state solution

Gesher: Social Liberalism; Economic and cost of living issues; Pro two-state solution

Kahol Lavan: Zionism; Secularism; Pro-Annexation

Meretz: Secularism; Pro two-state solution; Social Justice; Labor Zionism

Hadash: Marxism-Leninism; Eco-socialism; Non-Zionist; Pro two-state solution

Ta’al: Secularism; Anti-Zionist; Arab Nationalism

Balad: Pan-Arabism; Anti-Zionist; Socialist nationalism

Ra ’am: Islamism; Anti-Zionist; Pro two-state solution

Brief Background of April and September 2019 Elections

The three elections reflected the political divide over the subject of corruption and the role of religion in Israeli politics. The April 2019 election occurred in the background of contentions within the right-wing bloc comprising of Likud, Shas, United Torah Judaism (UTJ) Yamina and Yisrael Beiteinu over the application of mandatory conscription on the ultra-orthodox community. For Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu facing charges of corruption, the election was perceived as a litmus test. Netanyahu had allegedly accepted gifts and bought positive coverage from Yediot Aharonot newspaper and Walla news website. He is currently facing trial for fraud, bribery and breach of trust.1

The anti-corruption political wave prior to the election prompted the formation of Kahol Lavan on 21 February 2019 after Hosen L’Yisrael led by Benny Gantz and Gabi Ashkenazi, Yesh Atid led by Yair Lapid and Telem led by Moshe Ya’alon joined hands to defeat Netanyahu. The new party based on anti-corruption agenda accommodated politicians hailing from diverging ideological standpoints.2 It broadly presented itself as centre-right party seeking to reform the political structure ‘wrecked’ by the Netanyahu government. It therefore, sought to attract disillusioned right-wing voters facing economic inequality and fatigued by the political deadlock as well as left-wing Jewish voters disenchanted by the centre-left parties’ incapability to challenge Likud.3 It therefore, lacked ideological consistency which has been reflected in the 14 months existence of the party.

21st Knesset Election

Date: 9 April 2019

The first electoral stint of Kahol Lavan led by Benny Gantz in the April 2019 election was relatively successful after it managed to secure 35 seats, similar to Likud. Kahol Lavan along with its closest ideological partner, Labor party however, failed to consolidate a 61-seat majority in the 120 seat Knesset. Benjamin Netanyahu’s bid for government formation also failed after secularist Yisrael Beiteinu led by Avigdor Lieberman withdrew support over differences on application of mandatory conscription.4 Religious parties have objected to the imposition of mandatory conscription on Yeshiva students. Netanyahu’s failure to reconcile the religion-secular debate and accommodate diverse perspectives on national security eroded his right-wing coalition and impeded government formation. The erosion in the right-wing coalition continued in the September 2019 election.

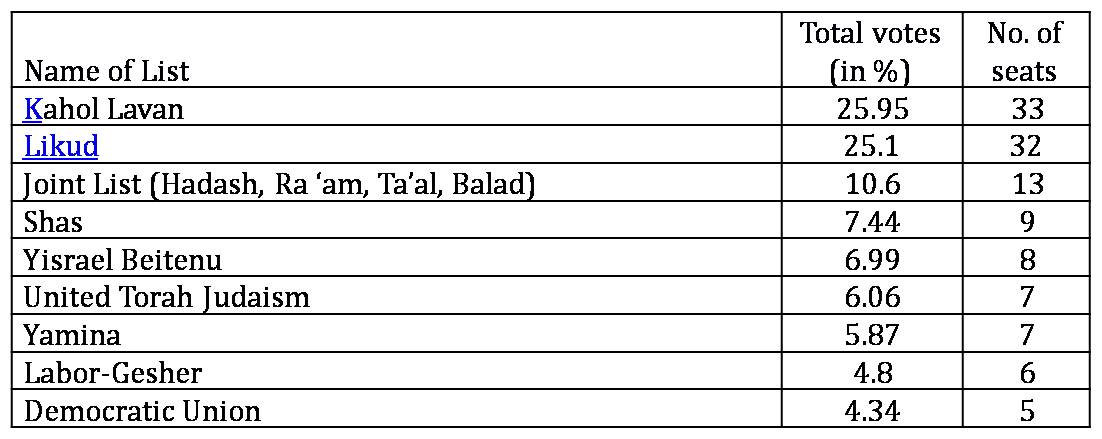

In September 2019 election, Kahol Lavan secured a slight lead with 33 seats. The right-wing coalition comprising Likud (32 seats), Shas (9 seats), UTJ (7 seats) and Yamina (7 seats) again failed to cross the 61 seats majority to form government. The prospect of unity government was floated following the election after Netanyahu submitted a list of guidelines to Kahol Lavan. Yisrael Beiteinu also indicated support for formation of a secular alliance with Likud and Kahol Lavan.

22nd Knesset Election

Date: 17 September 2019

Source: Knesset; Link: https://knesset.gov.il/description/eng/eng_mimshal_res22.htm

Kahol Lavan similar to Yisrael Beiteinu opted for moderating the role of religion in society by supporting egalitarian prayer space at the Western Wall; drafting ultra-orthodox citizens in the military; civil unions; opening limited public transport and businesses on Shabbat, the Jewish Day of Rest etc. Both Kahol Lavan and Yisrael Beiteinu rejected Netanyahu’s proposal of setting targets in drafting ultra-orthodox Israelis in the IDF and maintaining the status quo up to a year on religious subjects such as opening public transport and businesses on Shabbat. The political compromise therefore, failed after Likud refused to dissociate the religious parties from the unity government. The terms for rotating the position of the Prime Minister was also unspecified in Netanyahu’s guidelines.5

Moreover, the legal proceedings against Netanyahu complicated the political process after he failed to secure immunity from corruption charges. Gantz insisted that he would not be working with Netanyahu while he is under indictment. Kahol Lavan until the present election had maintained Netanyahu as threat to democracy. However, the onset of COVID-19 has re-organised the political alignment which would be discussed subsequently.

Dissecting March 2020 election

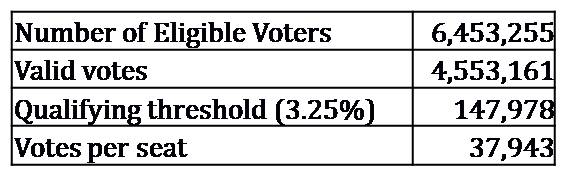

The latest election conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis witnessed a surprisingly high turnout of 71 percent with 4,579,931 eligible voters. The total turnout in April and September elections were at 67.9 percent and 69.4 percent respectively.6 Notably, 5630 quarantined Israelis were allowed to vote in designated polling stations.7

23rd Knesset Election

Date: March 2, 2020

The trends in the current election indicated similarity with the two previous elections. The prominence of the Zionist political left continued to further diminish and left-wing voters that traditionally voted for Labor or Meretz have moved towards the Kahol Lavan and the Joint List dominated by Israeli Arab leaders. For several left-wing voters, Kahol Lavan during the three elections has emerged as credible force against Netanyahu’s right-wing, hawkish political discourse that relies on appeasing the religious Jews. At the same time, the support for the Arab Joint List has increased among the left-wing Jewish voters. The Joint List comprising of three Arab parties i.e. Ra ‘am, Balad, Ta’al and Hadash, associated with the Israeli Communist Party have witnessed significant gains in the three elections winning 10 seats, 13 seats and 15 seats in April 2019; September 2019 and March 2020 elections respectively. The Joint List has emerged as the third largest bloc after Likud and Kahol Lavan.

The fractured political mandate and high voter polarisation has continued in the present election. After the failure of the right-wing coalition comprising of Likud, Yamina, Shas and UTJ to prove its majority, Netanyahu repeated his willingness to form national unity government with Kahol Lavan. The anti-Netanyahu camp, comprising of centrist, leftist, Arab parties and the right-wing Yisrael Beiteinu offered support to Kahol Lavan and Benny Gantz managed to secure a slim 61 seat majority. Gantz was reconciliatory when he stated that his government would serve both Jews and Arabs. Gantz on 15 March 2020 was offered the first opportunity to form government within four weeks period.8 Gantz during this period utilised his fragile majority to push for legislation prohibiting politicians facing criminal indictment from forming government.9 The legislation was essentially directed against Netanyahu.

The COVID-19 pandemic by mid-March 2020 had spread to the West Asian region including Israel. Benjamin Netanyahu as the caretaker Prime Minister took early measures to limit the spread of the pandemic in the Jewish state including prohibition on international travel; quarantine facilities and social distancing measures, increasing the number of tests and lockdown regulations.10 Netanyahu tactfully attempted to create a public consensus about his leadership’s capability to overcome the crisis. Likud also dispensed terrifying images on the consequences of the pandemic in the absence of his leadership. The Likud leader has historically utilized fear such as terrorism; xenophobia; Iranian nuclear bomb and presently the COVID-19 pandemic as political tool to consolidate power.11 The COVID-19 crisis also led to postponing Netanyahu’s trial until 24 May 2020 which was due to be held on 17 March.12 The opposition parties blamed Netanyahu for using the pandemic to save his political career.

Prime Minister Netanyahu nevertheless managed to gain high public approval for dealing with the crisis. Gantz’s public ratings among the centrist and right-wing Israelis at the same time fell and he was seen as an impediment in swift functioning to tackle the crisis.13 Moreover, the fragile anti-Netanyahu coalition led by Gantz collapsed after Gesher party leader Orly Levy backed out, followed by Kahol Lavan members, Tzvi Hauser, Yoaz Hendel and Omer Yankelevich. Former IDF Chief and leader of Hosen L’Yisrael party, Gabi Ashkenazi also withdrew support, questioning the viability of coalition government in which Arab parties and pro-settler, pro-annexation Yisrael Beiteinu are partners.14 Kahol Lavan also considered the alliance with the Arab parties as politically risky which may alienate its right-wing support base.

Gantz in the absence of majority faced with two choices. Firstly, to move ahead with fourth election which is highly unpopular due to ongoing pandemic and secondly, to join unity government with Likud under Netanyahu. Gantz opted for the second option compromising with its raison d’etre i.e. the fall of Netanyahu and bringing accountability in Israeli politics.

National Unity Government

Benny Gantz indicated his wilingess to move towards the unity government after he accepted the position of speaker with the backing of Likud on 26 March 2020. The preceeding speaker, Yuli Edelstein from Likud resigned on 25 March after facing criticism for refusing to re-open the Knesset due to the pandemic. Gantz had initially planned to place a speaker from his party to hasten legislation to fix term limits and disqualify Prime Ministers facing indictment.15 However, after assuming the position of speaker, he chose to protect Netanyahu from indictment to sustain the prospects of a unity government.16

Eventually, the national unity agreement was signed on 20 April 2020. According to terms of the unity agreement, the life span of the government is 36 months. Netanyahu would remain in the position of the Prime Minister for 18 months after which Gantz will take over. The agreement offers provisions for Netanyahu to resign early to face the trial during which Gantz would complete the 18 months term. It would allow Netanyahu to return and finish his term. In the case of dissolution of the Knesset during Netanyahu’s tenure, Gantz would take over as the interim Prime Minister. The 36-member cabinet would be equally divided between the two parties with Gantz controlling Defense, Foreign, Justice, Culture and Communications Ministry. The first six months have been designated as the emergency period in which legislations would exclusively focus on tackling the pandemic. The only exception agreed by both sides is the annexation of parts of West Bank after 1 July 2020.17

Constitutional experts have warned that the agreement would weaken the legislative authority of the Knesset and its capacity to oversee the conduct of the government. Both sides can veto any legislation depending on their will and the provision of no-confidence motion on the ruling government is unlikely due to the agreement. The terms of the agreement have also diminished the role of Knesset in changing the budget.18

The unity government is likely to result in a bloated and bifurcated government in which the security cabinet decisions and hiring and firing process of the cabinet members would be divided between the two blocs which are traditionally reserved for the Prime Minister. The Judicial Appointments Committee responsible for the selection of the Supreme Court judges is determined by the two parties. Gantz also assured that in case of disqualification of Netanyahu by the court, the government would be dissolved. It would strengthen Netanyahu’s position to control the appointment of judges and offer leverage to influence the decision of the trial and impede any verdict that may disqualify him from his constitutional position. Moreover, the Ministerial Committee for Legislation is also split between the two parties.19 The unity government described as ‘democratic ceasefire’ reflects the mutual suspicion between the two parties which may disrupt smooth political functioning.

Kahol Lavan’s bonhomie with its arch rival, Likud has been seen as betrayal by its supporters and protests emerged on 23 April 2020, expressing fears that the agreement would destroy the Knesset; dilute the quasi-constitutional Basic Laws and aid Netanyahu to evade justice.20 Yesh Atid and Telem leaders have backed out from the unity government and Yair Lapid accused Gantz of surrendering without a fight.21,22 Due to the lack of support by several key Yesh Atid and Telem members, the floor test for Gantz would be difficult and he islikely to rely on smaller parties to prove the political mandate.

The possibility of broad alliance with the Arab parties within the Kahol Lavan led alliance had brought glimmer of hope towards reconciliation within the Israeli society and progress in peace talks with the Palestinians. However, the expectations were dashed after Gantz opted for alliance with Likud. On the subject of Palestine, the Israeli state is likely to continue its hawkish posture. The former IDF Chief, Gantz’s policy coincides with Likud on issues such as maintaining security control over Palestinian territories, denying the right to return and indivisibility of Jerusalem. Gantz had reportedly previously made problematic statements calling for destruction in Gaza.23 The agreement entails the possibility of annexation of crucial Palestinian territories including Jordan Valley and illegal settlements after 1 July 2020 in compliance with the US President Donald Trump’s Peace Plan.24 The Palestinian Prime Minister, Mohammad Shtayyeh has called the arrangement as an Israeli annexation plan that would further disrupt the state-building process and suppress their rights.25 Palestinian Foreign Minister, Riyad al-Maliki has warned that Israel’s proposed annexation would effectively end the two-state solution.26

In so far as India is concerned it has de-hyphenated its relations with both Israel and Palestine based on its vital strategic interests. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has developed close personal friendship with Benjamin Netanyahu and both leaders spoke on 3 April 2020 to discuss on measures on tackling the pandemic. India has offered five tons of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) to Israel on 7 April. India is likely to favour an end to political instability to facilitate cross-party political decisions for overcoming the crisis.

India at the same time is committed to the two-state solution with East Jerusalem as the capital of the future Palestinian state. Therefore, the policy of annexation is seen as impediment to peaceful solution to the conflict.

Conclusion

The current Israeli political discourse is highly fragmented that has been unable to resolve the dilemmas on security, religion and political accountability. Kahol Lavan under Gantz was credited for reviving a strong opposition against Netanyahu during the three elections. However, the inability by either side to form government had prolonged the political deadlock. The national unity government facilitated partly due the ongoing crisis as well as differences within the anti-Netanyahu camp is considered by both parties as a way forward to tackle the crisis and prevent the possibility of fourth election. The new arrangement has emboldened the incumbent Prime Minister who may evade the alleged charges. It has also created the conditions to weaken the Knesset and the democratic and legal procedures as crucial decision-making would be reliant of the political interests of the two blocs. Moreover, the mutual distrust over each other’s intention is likely to continue that may disrupt the political process. Therefore, the fragile unity government is likely to contribute to the political deadlock and the possibility of the fourth election in the near future cannot be dismissed.

References

- BBC News, “Benjamin Netanyahu: What are the corruption charges?,” BBC News, November 21, 2019, at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47409739 (Accessed April 29, 2020).

- Middle East Monitor, “Israel’s Gantz and Lapid merge lists, agree premier rotation,” Middle East Monitor, February 21, 2019, at https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190221-israels-gantz-and-lapid-merge-lists-agree-premier-rotation/ (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- R. Baroud, “A Machiavellian Fiasco: How ‘Centrist’ Gantz Resurrected Netanyahu, Israel’s Right,” Middle East Monitor, April 20, 2020, at https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200420-a-machiavellian-fiasco-how-centrist-gantz-resurrected-netanyahu-israels-right/ (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- J. Lis, “Lieberman Blasts Netanyahu, Says He Won't Join His 'Jewish Law' Government,” Haaretz, May 27, 2019, at https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/lieberman-blasts-netanyahu-says-he-won-t-join-his-government-1.7288435 (Accessed April 26, 2020).

- J. Lis, “With Less Than a Week to Go, Gantz Rejects Netanyahu's Outline for Unity Government,” Haaretz, October 27, 2019, at https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/elections/.premium-with-less-than-a-week-to-go-gantz-rejects-netanyahu-s-outline-for-unity-government-1.8004747 (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- The Times of Israel, “Turnout highest since 2015 as voters defy predictions of apathy, virus fears,” The Times of Israel, March 2, 2019, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/turnout-highest-since-1999-as-voters-defy-predictions-of-apathy-virus-fears/ (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- R. Wootliff, “Out of quarantine, into the polling station. Then back to quarantine,” The Times of Israel, March 2, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/out-of-quarantine-into-the-polling-station-then-back-to-quarantine/ (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- R. Eglash, “Israel’s president gives Benny Gantz first chance at forming a government,” The Washington Post, March 16, 2020, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/israel-election-gantz-rivlin-netanyahu-liberman/2020/03/15/c5f251d0-66e1-11ea-b199-3a9799c54512_story.html (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- O. Holmes, “Israel's opposition head Benny Gantz wins support to form government,” The Guardian, March 15, 2020, at

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/15/israels-opposition-head-benny-gantz-wins-support-to-form-government (Accessed April 26, 2020). - i24 News, “Netanyahu announces three new measures to combat COVID-19,” i24 News, March 18, 2020, at https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/israel/1584473767-netanyahu-announces-three-new-measures-to-combat-covid-19 (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- A. Eldar, “How COVID-19 saved Netanyahu,” Al Jazeera, April 1, 2020, at https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/covid-19-saved-netanyahu-200401092744398.html (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- A. S. Barghoti, “Israel: Netanyahu’s trial postponed over coronavirus,” Anadolu Agency, March 15, 2020, at https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/israel-netanyahus-trial-postponed-over-coronavirus/1766704 (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- J. Krasna, “Securitization and Politics in the Israeli COVID-19 Response,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 13, 2020, at https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/04/securitization-and-politics-in-the-israeli-covid-19-response/ (Accessed 27, 2020).

- The Times of Israel, “Another Blue and White MK said to oppose minority government,” The Times of Israel, March 17, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/another-blue-and-white-mk-said-to-oppose-minority-government/ (Accessed April 29, 2020).

- J. Lis, “Gantz Voted in as Knesset Speaker, Paving Way for 'Emergency' Unity Government With Netanyahu,” Haaretz, March 26, 2020, at https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-kahol-lavan-on-verge-of-split-as-gantz-submits-his-name-for-knesset-speaker-1.8713168 (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- O. Holmes, “Benny Gantz elected Israeli speaker, signalling deal with Netanyahu,” The Guardian, March 26, 2020, at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/26/benny-gantz-elected-israeli-speaker-signalling-deal-with-netanyahu (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- H. R. Gur, “Israel’s new ‘unity’ government is neither united nor likely to govern well,” The Times of Israel, April 21, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/israels-new-unity-government-is-neither-united-nor-likely-to-govern-well/ (Accessed April 27, 2020).

- J. Lis, “Netanyahu-Gantz Coalition Deal Will Neutralize Israel's Legislature,” Haaretz, April 22, 2020, at https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-netanyahu-gantz-coalition-deal-will-neutralize-israel-s-legislature-1.8788533(Accessed April 28, 2020).

- H. R. Gur, “Monstrous coalition neuters Knesset. Should judges intervene? Will they?”, The Times of Israel, April 23, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/monstrous-coalition-deal-neuters-knesset-should-judges-intervene-will-they/ (Accessed April 25, 2020).

- T. Bateman, “Israel coalition deal a victory for Netanyahu forged in isolation,” BBC News, April 22, 2020, at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-52371410 (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- The Times of Israel, “Gantz’s former allies fume over coalition deal with Netanyahu,” The Times of Israel, April 20, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/gantzs-former-allies-fume-over-coalition-deal-with-netanyahu/ (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- R. Wootliff, “Lapid: I trusted Gantz, but he stole our votes and handed them to Netanyahu,” The Times of Israel, March 26, 2020, at https://www.timesofisrael.com/lapid-i-trusted-gantz-but-he-stole-our-votes-and-handed-them-to-netanyahu/ (Accessed April 25, 2020).

- The Palestine Chronicle, “Benny Gantz ‘Stole’ Gaza Destruction Footage for a Campaign Video,” The Palestine Chronicle, January 28, 2019, at https://www.palestinechronicle.com/benny-gantz-stole-gaza-destruction-footage-for-a-campaign-video/ (Accessed April 26, 2020).

- Peoples Dispatch, “The ‘new’ in Israel’s next govt.: Netanyahu as PM, annexation of Palestinian land to continue,” Peoples Dispatch, April 21, 2020, at

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2020/04/21/israels-new-government-netanyahu-as-pm-annexation-of-palestinian-land-to-continue/ (Accessed April 28, 2020). - Asharq Al-Awsat, “Shtayyeh: We Are Entering A New Phase With Israel,” Asharq Al-Awsat, April 28, 2020, at https://aawsat.com/english/home/article/2256896/shtayyeh-we-are-entering-new-phase-israel (Accessed April 29, 2020).

- Al Jazeera, “Arab League slams Israeli plan to annex occupied West Bank,” Al Jazeera, April 30, 2020, at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/arab-league-slams-israeli-plan-annex-occupied-west-bank-200430145602846.html (Accessed April 30, 2020).

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://static.timesofisrael.com/www/uploads/2019/09/F190923HZGPO01-e1569264533921-640x400.jpg

Post new comment