Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent comments that his new government, with support from the Trump Administration in the US will annex parts of the West Bank have, as expected, caused quite a flutter in the international community. Many have condemned the move, while members of the European Union, one of Israel’s most important trading partners, have warned against any such unilateral move. Within Israel, Netanyahu’s plans enjoy greater support from the public, but here too civil society and the national security community have expressed their reservations. Their main argument is that annexation will drown the last remaining vestiges of the two-state solution, and with that any negotiated settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that could allow both Jews and Arabs to coexist peacefully within their own secure borders.

Herein, Netanyahu’s critics are correct. Unilateral Israeli annexation of most or all Jewish settlements in the West Bank will make a future Palestinian state with territorial congruity nearly impossible. Additionally, it will also entangle the Jewish and Arab populations in a manner that will threaten Israel’s existence as a Jewish-majority, democratic state. But while each of these arguments is valid, they are still anchored to the premise that a state for Palestinians is the key to peace between the peoples.

‘Westplaining’ Palestinian Statehood

This premise is problematic because Palestinians have, in fact, repeatedly rejected offers for statehood. Instead, they have made it amply clear that what they want, more than sovereignty, is the undiluted right to return for all those defined as Palestinian refugees. This argument is succinctly laid out by Israeli journalist Adi Schwartz and former Knesset Member Einat Wilf in their book, the War of Return. Published in Hebrew in 2018, the book has recently been translated into English, and shines the spotlight on this important issue. The right to return is in fact one of the most important drivers (alongside the status of Jerusalem) for the Palestinian struggle. To write it off as cheap rhetoric or just a bargaining chip for the Palestinian side, as Western interlocutors often do, is what Schwartz and Wilf describe as ‘Westplaining’.

Therefore to understand the actual roots of the conflict, one must go back to the 1947-49 war--when tens of thousands of Arabs were first displaced from their homes, upon the establishment of the State of Israel. This article is a deep dive into the first of the Arab-Israeli wars.

The First Arab-Israeli War (1947-49)

The 1947-49 war had two distinct phases. The first phase started on November 30, 1947, the day after the UN General Assembly passed the plan to partition British-held Mandatory Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The plan was accepted by the former, rejected by the latter, and immediately sparked a guerrilla war in the region. This phase continued till May 14, 1948, when British forces officially withdrew from Palestine. The next day, Prime Minister Ben Gurion announced the establishment of the State of Israel. Immediately afterwards, six Arab armies launched a full frontal attack on the new state, thereby marking the beginning of the second phase of the war. This war ended in July 1949 when Israel militarily defeated its Arab opponents and an armistice agreement was signed.

The Situation in Mandatory Palestine on the Eve of the War

The Arabs were the majority in the region but there were Jewish Yishuv who had strongholds in places such as Tel Aviv-Yaffo and along the coastal plains, Tiberias, the eastern Galilee, and the Jezreel Valley. In fact, contrary to popular perception that Jews only came to Israel after the Holocaust, there were in fact many old Jewish communities that had lived in the area for a much longer time.

The oldest among them can be traced through the Ottoman era, right back up to the 13th century. In fact, on the eve of the arrival of the Zionist Jews, i.e. those who would be emigrating to Palestine with the distinct aim of re-establishing a modern Jewish state in the ancient land of Eretz Yisrael, there was already a modest but longstanding Jewish presence in the region, estimated at 13,000 to 20,000, while Muslims in the region were estimated at around 4, 00,000. Between 1881 and 1947/48, there were six waves of Jewish Zionist immigration (called Aliyah) to Palestine. These immigrants along with the older residents comprised the Yishuv, the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine. Initially, the Arab population was mostly indifferent to Jewish immigration, but as the numbers grew and the newer immigrants became more assertive, relations frayed and often turned violent.

On the day that the UN General Assembly passed the partition plan, the Jewish population of Mandatory Palestine was estimated at around 6,50,000 while Arab Muslims were nearly double that number at about 1.3 million. The region was already a tinderbox, and hostilities broke out in less than 24 hours. On the morning of November 30, Arabs ambushed a bus in Kfar Syrkin in central Israel and killed five Jews. Two more were killed aboard a second bus, and a third near the Tel Aviv-Yafo border.

The Jewish Yishuv was defended by its own militia, primarily, the Hagannah (which eventually became the Israel Defence Forces), it’s elite strike force the Palmach, as well as by more militant, off-shoot groups, such as the Irgun and Lehi, which often used terror tactics to achieve their goals. On the Arab side, the main fighting force was the Arab Liberation Army which was set up by the Arab League, based out of Damascus, and manned mostly by volunteers from the neighbouring Arab states. The ALA was led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji and operated mostly in north Palestine. There were also several smaller local militias such as the one led by Qawuqji’s rival Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini and his deputy who operated in the hills of Jerusalem and Ramallah.

Also in the fray were the British Army and police, but only nominally so. Till May 1948, Palestine was still technically under British rule, but British soldiers and police officers usually took a mixed approach to the conflict. On some occasions, they provided protection to Jewish convoys and outposts; on others, they chose not to intervene even as violent mobs went on the rampage; and in yet other cases, they sided with the Arabs.

War Begins -- Initial Arab Victories

In the early months of the conflict, the Arabs were definitely on the winning side. They were initiating the attacks and had been able to inflict heavy losses by targeting Jewish convoys and blocking key arterial roads that connected otherwise-isolated Jewish settlements. In fact, the Arabs had even successfully cut off the supply lines to the Jewish part of Jerusalem. Initially, the Hagannah’s response was defensive but included retaliatory attacks. Soon enough though, these attacks were expanded to become a much wider terror campaign by the end of 1947, to which the Irgun and Lehi contributed significantly.

But the terror campaign brought only limited dividends. The Arabs still controlled the arterial roads and Jewish settlements were under siege. The British were preparing to leave and were much less inclined to protect Jewish convoys. Even reaching Jerusalem was becoming difficult. Meanwhile, the international community had begun considering whether to postpone partition and bring all of Palestine under UN trusteeship. As the Yishuv saw it, their hard won state was slipping through their fingers. So, in April 1948, the Hagganah, which by then had reorganised itself to form the Israeli Defence Forces, changed its strategy. It went on the offensive with the clear goal of securing a politically and militarily contiguous Jewish state. This was Tochnit Dalet or Plan D. It had to be completed before the British left and the Arab armies, which had been holding back all these months, inevitably invaded the new state.

The Controversial Plan D

The significance of Plan D in creating the Palestinian refugee crisis has been hotly debated because, as official documents now show, it permitted Jewish soldiers to clear out any local Arab resistance. How exactly this was to be done was usually decided at the local level, but the general consensus in the Yishuv was that the fewer the Arabs, the better it would be--both militarily and politically, as Israel Shahak notes. According to Palestinian historian Khalid Walidi who has worked extensively on the 1947-49 exodus argues that Plan D was, indeed, an expulsion plan; but Israeli historian Benny Morris argues that there was never an official Zionist policy document for Arab expulsion. Both, however, agree that the impending invasion of the Arab armies made the Palestinian exodus a strategic necessity for the Zionists, and this was indeed ultimate result of Plan D (as it unravelled against the backdrop of a host of other geopolitical considerations).

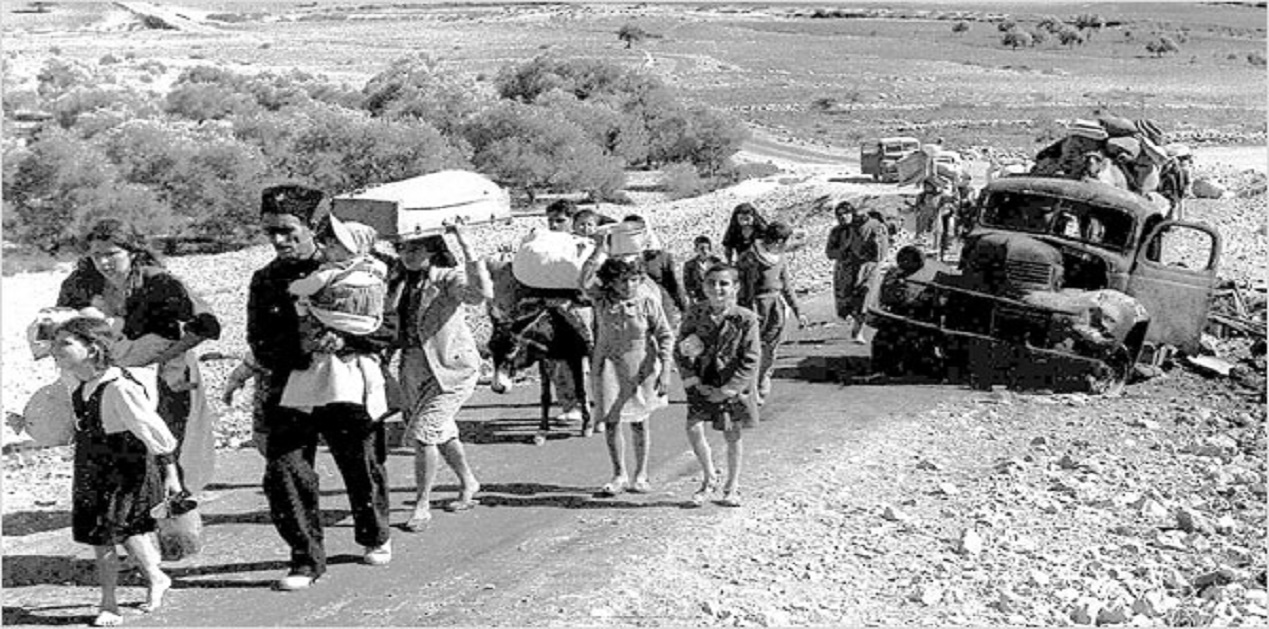

The Exodus of the Palestinians

The exodus began the day the war began. Wealthy Arab families began to leave as soon as hostilities erupted on November 30, 1947. Between December 1947 and March 1948, fearing anarchy and terror on the streets, and worrying about the possibility of living either under Jewish rule or the under the thumb of Arab militias, most rich and middle class Arab families fled from their homes--especially those living in areas that were most certainly going to be part of or close to the Jewish state, such as Haifa, Jaffa and west Jerusalem (which were also the places that saw most of the fighting). Most of them moved from the Jewish coastal plains to neighbouring Arab-majority cities and capitals such as Damascus, Nablus, Amman, Beirut, Gaza and Cairo; hoping that this would only be a temporary arrangement. The flight of the rich also sparked fear among the poor who watched the fighting intensify, even as unemployment soared, supply lines were disrupted, and the British safety-net was lost. An overwhelming sense of economic and social collapse permeated Arab Palestine, compelling even the poor to pack up and move.

There was also an element of psychological warfare that hastened the Palestinian exodus, as both Morris and Khalidi show in their research. Morris describes this as the ‘atrocity factor’ wherein, apart from the terror campaign of the Irgun and the Lehi, a handful of actual Jewish atrocities (such as the Deir Yassin massacre which was so horrific that even the Yishuv leadership condemned it) were amplified by both sides to spook the residents. The Jewish groups did it to accelerate the exodus; while the Arab leadership and media did it to shame their opponents and gain international sympathy.

Indeed, it is often forgotten that while the Yishuv played its part in the Arab exodus, the Palestinian leadership also had a responsibility to protect its people--and failed spectacularly. As Morris shows, the Arab Higher Committee, established by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, offered no concrete guidelines to its people. On some occasions, it actively evacuated entire villages (which was also done by the invading Arab armies from May 1948 onwards), while on other occasions, it opposed the exodus, often asking military-aged males to stay back and fight. Yet it’s own members and their families had already moved out, and the poor were left to their own devices.

The Arab situation worsened as Jewish forces went on the offensive and defeated the ALA and other Palestinian guerilla forces. As Jewish troops took over towns and villages, Arab morale cracked. Morris describes a domino effect in the Arab areas: After Haifa fell, Arabs from surrounding Balad al Sheikh and Hawassa fled; after Jaffa fell, the villages of Salama, Kheiriya and Yazur were abandoned; and after Safed, it was Dhahiriya Tahta, Sammu‘i and Meirun. The IDF may have had an unwritten permission to forcefully expel Arab residents, but the option was sparingly used in the early months of the conflict.

In the latter half of the war, Israeli forces did in fact meet more resistance from Arab civilians; and in such cases, the former also showed much greater willingness to expel residents. This was partly in keeping with the Zionist view the Jewish state would be better off without a large Arab population, as Shahak notes, and but also the result of more immediate strategic military calculation. For example, as Morris explains, the large wave of refugees that fled to Jordan, Lebanon, the Upper Galilee, and the Gaza Strip in July 1948 was the result of IDF operations that were meant to push back Arab forces closing in on Tel Aviv and secure the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road. Also, these operations were triggered because Arab forces chose not to extend the ceasefire that had been in place through the previous month.

Similarly, the flight of another 2,00,000-2,30,000 Arabs in October-November 1948 was also the direct result of two major IDF operations but neither was designed for that purpose. In the north, Operation Hiram was meant to repel the ALA from the central Galilee; and in the south, Operation Yoav was meant to defeat the Egyptian army and secure the Negev, where more than 20 Jewish settlements lay besieged, and which the international community was already considering awarding to the Palestinians.

The two operations also created two very different sets of footprints. In the north, where the IDF faced a much weaker enemy in the ALA and much less resistance from the local population which included a significant number of Christians and Druze, almost half of the Arab population remained in place in the immediate aftermath of the operation. In the south, however, where the population was almost uniformly Muslim, where the IDF was led by a commander who preferred not to have any Arabs in his area, and where the IDF faced a much more serious enemy and responded with a much heavier hand, almost all the Arab villages were depopulated.

The exodus continued even after the war, as Israel decided to secure its new and still hotly contested border areas. These frontier areas had almost no Jewish settlements and were instead littered with Arab communities whose loyalty to the Jewish state was questionable at best. From a security point of view, they simply had to go. Some were moved to other Israeli Arab villages in the interiors, most others were expelled.

Closing the Doors to Palestinian Return

The scale and swiftness of the Palestinian exodus, as it unravelled though the war, had taken almost everyone by surprise. The talk of return had begun almost immediately after the first wave of refugees fled. But as more people were displaced, and the burden of the refugee crisis in neighbouring countries grew manifold, the international community’s pressure on Israel to take back the Arabs also intensified. Soon enough, the repatriation of the refugees dominated every Arab-Israeli agenda. On Israel’s side, there was a consensus that there was no scope for return, but Ben Gurion’s government couldn’t afford to entirely ignore the international community either.

The Lausanne conference was convened to discuss the matter, but neither party was ready to budge. Israel, especially, having scripted for itself a stellar victory, was satisfied with the status quo. Eventually, under much American pressure, Israel made a small offer to take back 1,00,000 refugees--less than 1/7th of the total refugee population--and, as expected, this was rejected outright as too little, too late.

Either way, by the end of the war, mass repatriation was nearly impossible. Apart from the fact that such a programme would threaten Israel’s still precarious security situation and pull at its Jewish democratic character, there were also hard logistical issues to contend with. Some of the Arab villages had been destroyed; many others had been re-settled with Jewish immigrants who were still pouring in from Europe (after the Holocaust) and from other Arab countries (which had banished their centuries-old Jewish communities to protest the establishment of Israel). The refugees wanted to come home, but by this time, there was no home for them to come back to. To make matters worse, the Arab countries, where hundreds of thousands of Palestinians lived in squalid refugee camps had refused to absorb them. Instead, they argued that it was Israel’s responsibility to take them back.

The Refugee Situation Today

As Jalal Al Husseini and Riccardo Bocco show in their 2010 study, by keeping the Palestinians as refugees, the Arab states have ensured the durability of the Right to Return, as enshrined in the UNGA Resolution 194--which, in turn, they have used as a political weapon against Israel. The Palestinians face a similar dilemma with regard to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (commonly known as UNRWA) as well. Registration with the UNRWA is necessary to access UN relief and other benefits, but the tag of a refugee, more than 70 years after the war, is equally undesirable, especially for later-generation refugees born and raised in the Diaspora.

Indeed, this multi-generational extension of refugee status through the UNRWA is also unique to the Palestinians. It emerged in part because, as Ilana Feldman explains, UNRWA was just a relief organisation and its definition of a Palestinian refugee was not designed to delineate the scope of the overall Palestinian loss but only to ascertain who needed the agency’s assistance. What this meant was that some legitimate candidates were not given refugee status because they didn’t need UNRWA assistance; while others who were not technically refugees, such as the children and grandchildren of the original refugees, were eventually registered as such because it would have been inhumane to deny them assistance otherwise. Moreover, as Husseini and Bocco note, today, UNRWA, a unique UN agency that caters only to Palestinians, has become a quasi state of sorts. So even though the agency’s mandate was always about relief, not rights; an UNRWA registration card is seen as a ‘passport to Palestine’ -- which remains at the core of Palestinian political aspirations.

References:

- Al Husseini, J., & Bocco, R. (2009). The status of the Palestinian refugees in the Near East: The right of return and UNRWA in perspective. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 28(2-3), 260-285.

- Feldman, I. (2012). The challenge of categories: UNRWA and the definition of a ‘Palestine refugee’.

- Journal of Refugee Studies, 25(3), 387-406.

- Khalidi, W. (1988). Plan Dalet: Master plan for the conquest of Palestine. Journal of Palestine Studies, 18(1), 4-33.

- Khalidi, W. (2005). Why did the Palestinians leave, revisited. Journal of Palestine Studies, 34(2), 42-54.

- Morris, B. (2004). The birth of the Palestinian refugee problem revisited (Vol. 18). Cambridge University Press.

- Morris, B. (2011). Righteous victims: a history of the Zionist-Arab conflict, 1881-1998. Vintage.

- Schwartz, A. and Wilf, E. (2020). The War of Return: How Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace. All Points Books.

- Shahak, I. (1989). A History of the Concept of "Transfer" in Zionism. Journal of Palestine Studies, 18(3), 22-37. doi:10.2307/2537340

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b5/Palestinian_refugees.jpg

Post new comment