The Chinese characteristics in hybrid warfare can be traced to Sun Zu’s classic Art of War. “To fight and conquer in all battles is not the supreme excellence; the supreme excellence is in breaking enemy’s resistance without fighting.”1 This reflects the oriental thought that violence is the last step towards achieving the national aim. Five thousand years later, similar notes have been echoed in 1999 by two colonels in the People's Liberation Army of China, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, when they released a book on military strategy called ‘Unrestricted Warfare’, which according to Chinese translation reads as "Warfare beyond Bounds". In chapter 5 of the book, it says "The great masters of warfare techniques during the 21st century will be those who employ innovative methods to recombine various capabilities so as to attain tactical, campaign and strategic goals."2

In 2003, the Chinese Communist Party approved and the Central Military Commission adopted the concept of ‘Three Warfares’ to include ‘public opinion, psychological and legal warfare’. A study for Net Assessment Directorate, Office of Secretary of Defence, concluded that if the objective of the war is to acquire resource, influence and territory and to project will – China’s Three Warfare is war by other means.3 In the same study Commodore Uday Bhaskar has argued “that the core objective behind the Three Warfare concept is not to seek outright victory on any given matter, but to use its elements as a subtle, Trojan horse means to realise the desired end .”4 The Chinese strategy is thus now going back to the philosophy of Sun Zu, i.e., to win the wars without fighting. The use of economics is inherent in the ‘Three Warfares’ strategy, whether it is influencing public opinion or fighting a legal warfare.

The extraordinary rise of China in the hierarchy of the power is the direct outcome of the spectacular economic growth. The 30 years of robust economic growth has provided China with the required economic and muscle power to assert itself in the comity of nations. China has successfully used the increased economic power in shaping the geopolitics to its advantage. This paper will bring out how China has used its economic might as the most potent weapon of its strategy of unrestricted warfare.

Preserving the Core Interest: Reunification with Taiwan

Reunification with Taiwan remains the core interest of China. On Jan 02 2019, President Xi in his speech claimed that the Chinese dream (of national reunification) is the common dream of compatriots across the strait. 5 Earlier, on the occasion of 19 Congress, on Oct 18 2017, Xi had announced that National reunification will be achieved by 2049.6 Not ruling out the use of force, albeit in the last few decades, China has put in place a full range of geo-economic instruments to preserve its core interest. Armed with economic strength China now relies more and more on strategy of economic encirclement and penetration to force Taiwan towards unification.7 These instruments or policies are being applied in two forms: First being the multilateral, wherein with the aim to isolate Taiwan internationally, China has been using geo-economics; and secondly, by bilateral engagement, in which it uses economic policies to engage Taiwan directly, thereby penetrating the Taiwanese society. 8 These two strategies are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs:-

- Diplomatic Isolation of Taiwan. In accordance with ‘One China Policy’, China proclaims Taiwan as inalienable part of China. Hence technically no country can have diplomatic relations with China and Taiwan simultaneously. China has been aggressively pushing One China Policy and using economic threats in terms of sanctions against countries which endorse Taiwan’s independent status.9 In 2018 alone, El Salvador and Burkina Faso have renounced their diplomatic relations with Taiwan.10 There are reports that when Taiwan showed its inability to fund construction of a port for El Salvador due to reasons of unviability, the Chinese stepped in and rest is history. Now, there are only 17 countries left which have diplomatic relations with Taiwan as an independent country.

- Penetrating Taiwanese Society. China has been exerting economic pressures which impact the life of a common Taiwanese citizen. In 1995, when ROC President Lee Teng-hui gave a speech asserting the de facto status of ROC on Taiwan, China reacted with threat of war by test firing missiles and conducting military exercises.

Simultaneously, there was a crash in Taiwan stock exchange (TAIEX) which led to a loss of approx. 30% of its total value. While China denied any direct hand, but speculations were strong about the Chinese hand.11 Chinese ability to penetrate directly improved from the year 2000 onwards, when the fifty-year-old ban in Taiwan to trade and invest directly with mainland China was removed by the President of Taiwan. China became the largest trading partner of Taiwan within three years of lifting of the ban. Today China (including Hong Kong) accounts for nearly 43% of Taiwanese exports.12 This growing dependence of Taiwan has helped China to toughen its stance on political and military negotiations. China has been actively supporting the Kuomintang Party in the internal elections of Taiwan, which is known as a pro-unification party. A clear indication of this was the huge jump in TAIEX in 2008, when Ma Ying-Jeou was elected as president of Taiwan. Ma paid back the Chinese by signing a cross-strait currency swap agreement in Aug 2012, which provides Beijing an effective leverage in Taiwan’s economy. China has been slowly and steadily making overtures that will indirectly push Taiwan towards the unification.

Simultaneously, there was a crash in Taiwan stock exchange (TAIEX) which led to a loss of approx. 30% of its total value. While China denied any direct hand, but speculations were strong about the Chinese hand.11 Chinese ability to penetrate directly improved from the year 2000 onwards, when the fifty-year-old ban in Taiwan to trade and invest directly with mainland China was removed by the President of Taiwan. China became the largest trading partner of Taiwan within three years of lifting of the ban. Today China (including Hong Kong) accounts for nearly 43% of Taiwanese exports.12 This growing dependence of Taiwan has helped China to toughen its stance on political and military negotiations. China has been actively supporting the Kuomintang Party in the internal elections of Taiwan, which is known as a pro-unification party. A clear indication of this was the huge jump in TAIEX in 2008, when Ma Ying-Jeou was elected as president of Taiwan. Ma paid back the Chinese by signing a cross-strait currency swap agreement in Aug 2012, which provides Beijing an effective leverage in Taiwan’s economy. China has been slowly and steadily making overtures that will indirectly push Taiwan towards the unification.

Protecting Territorial Sovereignty

China has used economic warfare as a strategic weapon on the sovereignty dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands chain.13 In 2010, after the arrest of the captain of a Chinese fishing trawler when it collided with Japanese coast guard ships, China retaliated by putting a sanction on export of rare earth minerals and metals to Japan. These minerals are a crucial component of electrical equipment which Japan exports to the US and the European countries. This ban forced Japan to release not only the prisoner, but also established a new dimension.14 Having suffered the ban, the Japanese industrial giants like Hitachi and Toyota shifted their plants to China. Ban on rare earth materials needs to be seen as economic coercion by which China successfully used a crisis to achieve three strategic aims, first to secure the release of the captain of the fishing trawler which had become an emotive issue, second to send a strong signal to Japan over its sovereignty rights on islands, and lastly to consolidate its market share in global supply chain.15 Later, as the Japanese government bought a portion of the Senkaku Island, the dispute aggravated as China became more aggressive in implementing the trade sanctions and ban on the export of rare earth minerals.

Expanding Influence in Southeast Asia

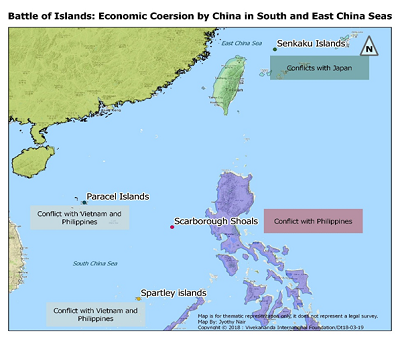

The geo-economic strategy of China in Southeast Asia, apart from increasing its influence in the region, aims to achieve three deeply interrelated objectives.  Firstly, to check the US alliances in the region, secondly to penalize and impose cost on any nation that acts adversely on Chinese territorial and maritime claims and to preserve the old friends like Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. 16 Any opposition or representation against China’s claim of “nine dash line” in South China Sea, on Paracel and Spartley islands, Scarborough and James Shoals or many other such disputes extending up to Ntuma islands North of Indonesia is likely to invite immediate reaction from China it terms of economic coercion.

Firstly, to check the US alliances in the region, secondly to penalize and impose cost on any nation that acts adversely on Chinese territorial and maritime claims and to preserve the old friends like Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. 16 Any opposition or representation against China’s claim of “nine dash line” in South China Sea, on Paracel and Spartley islands, Scarborough and James Shoals or many other such disputes extending up to Ntuma islands North of Indonesia is likely to invite immediate reaction from China it terms of economic coercion.

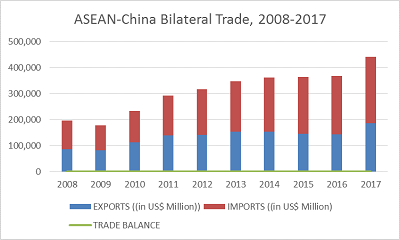

In 2012, when a Philippine naval ship attempted to arrest the Chinese fishing trawlers close to the disputed Scarborough Shoal, China banned the import of 15 containers of bananas from Philippines, followed by a ban on other fruits and vegetables which hit the local farmers very hard. As the country was managing the woes of farmers, China swiftly occupied the shoal. 17 The vulnerabilities of ASEAN countries increases with the fact that China not only remains the largest trading partner of ASEAN as a block, but individually also it is the largest trading partner with most of the countries. The increased dependency of ASEAN nations on China is explained in the graph.

Protecting National Interest

There are numerous incidents which indicate that China has not hesitated in enforcing economic coercion against the nations which have acted/apparently acted against the Chinese national interest. One the most sensitive issue is of interacting with or hosting Dalai Lama. A study in the year 2010, published in the Journal of International Economics which studied exports of 159 countries to China, concluded that the countries whose leaders met Dalai Lama suffered a loss of trade with China, in terms of exports falling from 8.1 to 16.9 percent. 18 In 2016, when Mongolia hosted Dalai Lama, China reacted strongly by blocking the important trade route between the two nations and also imposing additional tariffs.19

In 2016-17, when the US deployed THAAD missiles in South Korea, China hit back with economic sanctions against South Korea. As per the Staff Research Report of the US-China Economic and Security Commission Report of 2017, the Chinese regulators banned a considerable range of Korean products that were being exported to China, like cosmetics, air purifiers, video games etc. By the first-quarter end in 2017, the consumer export had dropped by 5.6 percent. Korean auto giants like Hyundai and Kia had a 52 percent drop in sales in China. The industry to suffer biggest hit was tourism as 47 percent of foreign tourist visiting Korea were Chinese. There was a drop of 66 percent in Chinese tourists to Korea.20 In 2009, some Uighurs had taken shelter in Cambodia and were seeking asylum. However, in spite of the UN objections, Cambodia repatriated them to China to face prosecution in connection with the violent protest that had taken place in Xinjiang. It is reported that Cambodia succumbed to pressure and threat by China. Cambodia was soon gifted with grants and loans worth 1.2 billion US dollars by China.21

BRI the Great Chinese Dream or a Weapon of Debt Trap Diplomacy

The ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a manifestation of Chinese economic diplomacy, wherein China has been targeting the vulnerable nations through loans and getting them in the debt trap. President Xi, during the 19th National Party Congress, formally adopted the Belt and Road Initiative under the Party Constitution as a part of resolution to achieve “shared growth through discussion and collaboration”. The project is being seen as the great ‘Chinese Dream’ and an ambitious attempt to challenge the US domination. While these aspects are true, but the more important fact is that China needed new markets to support the export-based economy. The economic growth plateaued since early part of the second decade of the century. The Chinese white paper on Defence of 2013 laid out a new role for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to protect the Chinese assets beyond the main land. It was envisaged by the Chinese government that expansion of trade to new frontiers was essential for the survival of state. Hence, manifestation of the BRI is the outcome of a necessity, and is being sold as “shared growth through discussion and collaboration”.

The BRI program is a win-win situation for both, the Chinese government and the Chinese infrastructure conglomerates. Through BRI, by constructing infrastructure in the poor countries, China has been able to manage the excess availability/supply of dollar which in any case was not generating enough returns. China is offering loans to the economically weak nations for infrastructure projects. The contracts for such projects are being granted to Chinese companies which further employ Chinese labour. Apart from generating employment, China has also been able to increase its strategic influence and capture new markets. China, knowing very well that these countries will not be able to pay back the loan is still investing in these countries. As a matter of fact, the terms of loan are made such that on the face of it the offer looks too attractive to refuse, but soon even the payment of interest on these loans becomes unviable. According to Center of Global Development policy paper 121 March 2018, the contracts are opaque, there is a lack of transparency and the contracts generally do not follow international norms. 22

There have been cases wherein countries have been lured into construction of infrastructure projects which they did not even need. The construction of the port at Hambantota in Sri Lanka is one such case wherein the Chinese offered to construct a port which did not have any economic viability. The offer was such that the Sri Lankan government fell in the trap. On completion of the port, the Sri Lankan government was paying 90 percent of its revenue earned in servicing of the debt it had taken for construction of the port at Hambantota. In order to pay the accumulated interest and service the debt, the Sri Lankan government had to lease out the Hambantota port to the Chinese for a period of 99 years.

Another case study is of Montenegro, where the country accepted the Chinese proposal to construct a super highway connecting the port of Bar on Adriatic Sea to the land-locked Serbia. After the first phase of construction, Montenegro is under a debt of approximately one billion USD, for the balance three phases approximately another 1.2 billion USD would be required. For Montenegro, a country with a population of just 6, 20,000, even the payment of interest in not feasible. According to a report by the World Bank, there is a minimum requirement of 25000 vehicles using the highway to justify the construction, however, as per the current estimate, traffic on the busiest stretch won’t cross 6000 vehicles.23 The debt to GDP ratio in Montenegro has gone beyond 80%, leading to an increase of taxes and a temporary freeze on public sector wages. Feasibility studies carried out by French firm Louis Berger for the Montenegrin government and another by a US company for the European Investment Bank have opined negatively on the prospects of the project. However, another study funded by Export-Import Bank of China found the project viable, though the findings were never made public. A point of interest is that the first phase of the project was constructed by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) with the loans from Export-Import Bank of China. 24 This raises the questions on the entire process and the business practices followed by China.

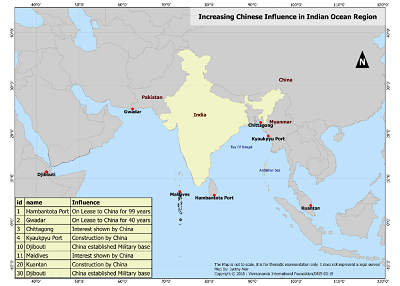

Increasing Influence in Indian Ocean Region (IOR) by Capturing Ports at Strategic Locations through Economic Coercion

Chinese dependence on the Sea lanes of communications in IOR region is a known fact. More than 80% of Chinese trade passes through IOR. China has been using all ways and means to increase its influence in the IOR region. In the last few years, it has acquired/ built/operat from strategically located ports in the IOR. This ‘string of pearls’ strategy has been discussed widely amongst the scholars, academia and strategists. But what is more important is how China has gone about gaining control over these ports. The ports of Hambantota in Sri Lanka, as discussed earlier, has been acquired by aggressive and predatory economic takeover. Kuntan in Malaysia, Kyauk Pyu deep-water port in Myanmar, Hambantota in Sri Lanka and Gwadar in Pakistan are some of the ports that China is funding and building. Another country under heavy Chinese debt trap and which may end up handing over of construction and subsequently control of a strategic port to China is Maldives. China has shown keen interest in constructing a port in Maldives25. According to Reuters and Forbes, Maldives already owes China 3.2 billion USD, which is more than 8000 USD per individual of the small country. 26 The debt to GDP ratio of Maldives has crossed over 100%. Maldives is now moving on the same path as Sri Lanka, which had to undergo a debt-swap agreement and hand over the Hambantota port to China.

Chinese dependence on the Sea lanes of communications in IOR region is a known fact. More than 80% of Chinese trade passes through IOR. China has been using all ways and means to increase its influence in the IOR region. In the last few years, it has acquired/ built/operat from strategically located ports in the IOR. This ‘string of pearls’ strategy has been discussed widely amongst the scholars, academia and strategists. But what is more important is how China has gone about gaining control over these ports. The ports of Hambantota in Sri Lanka, as discussed earlier, has been acquired by aggressive and predatory economic takeover. Kuntan in Malaysia, Kyauk Pyu deep-water port in Myanmar, Hambantota in Sri Lanka and Gwadar in Pakistan are some of the ports that China is funding and building. Another country under heavy Chinese debt trap and which may end up handing over of construction and subsequently control of a strategic port to China is Maldives. China has shown keen interest in constructing a port in Maldives25. According to Reuters and Forbes, Maldives already owes China 3.2 billion USD, which is more than 8000 USD per individual of the small country. 26 The debt to GDP ratio of Maldives has crossed over 100%. Maldives is now moving on the same path as Sri Lanka, which had to undergo a debt-swap agreement and hand over the Hambantota port to China.

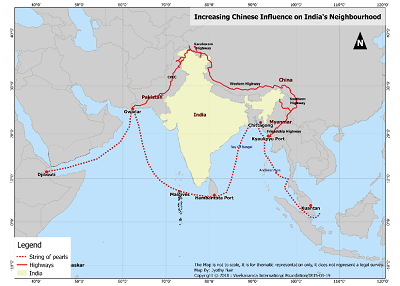

Encircling India with Infrastructure-Debt Trap Diplomacy

In Asia, China and India are the two biggest countries in terms of geography, economy, defence forces and human resources – they also happen to share the longest-disputed land border. Both the countries are amongst the fastest growing nations, hence the competition, rivalry and conflict in the common area of influence are natural. While, India considers China as the biggest strategic challenge, China too aims to slow down or restrict the increasing influence of India. China has been able to achieve the strategic aim of encircling India and increase its strategic leverage on Indian neighbourhood by successfully using its economic might.

The China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is the flagship project of the Chinese infrastructure trap diplomacy. CPEC connecting Gwadar to Karakoram Highway (KKH) has both the economic and strategic importance for both China and Pakistan. As per Nikkei Asian Review report, China is the biggest lender to Pakistan, accounting for more than 19 billion USD out of a debt of approximately 90 billion USD.27 Bulk of the Chinese loans are due to funding of CPEC. The capacity of Pakistan to pay back the loan is under severe skepticism as Pakistan was at the brink of a financial collapse and was rescued by Saudi Arab and the UAE.28 Point to note is that the payment of CPEC loans is yet to start. As a collateral to the loan, Pakistan has handed over the operation of Gwadar port to China for a period of 40 years.  It is reported that, according to the agreement, the state-run China Overseas Port Holding Company will take 91 percent of revenue collected from terminal and marine operations and 85 percent of gross operations revenue from the Gwadar free zone.29 There are reports of China establishing a military base at Jiwani which is just 80 km West of Gwadar.30 The CPEC, connecting Gwadar to KKH, which further connects the Western Highway, encircles India and provides China a strategic advantage.31 Access to Gwadar Port, a strategic highway all along India’s frontier and a vassal state which has lost its strategic autonomy, all provide a tremendous strategic advantage to China against India in long-term perspective.

It is reported that, according to the agreement, the state-run China Overseas Port Holding Company will take 91 percent of revenue collected from terminal and marine operations and 85 percent of gross operations revenue from the Gwadar free zone.29 There are reports of China establishing a military base at Jiwani which is just 80 km West of Gwadar.30 The CPEC, connecting Gwadar to KKH, which further connects the Western Highway, encircles India and provides China a strategic advantage.31 Access to Gwadar Port, a strategic highway all along India’s frontier and a vassal state which has lost its strategic autonomy, all provide a tremendous strategic advantage to China against India in long-term perspective.

Apart from Pakistan, the increasing Chinese footprints in Nepal, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Maldives are of concern to India. Chinese investments at these places have been aggressive, not just in industry. In fact, the major share of investments has been in infrastructure and energy. Together, these sectors claim for 83% of Chinese investments these countries. Nepal is the next country after Sri Lanka and Pakistan, which is on the verge of falling into the debt trap of China. China is the largest foreign investor in Nepal. Its investment has shot up from just 1.81 million USD in 2003 to 174 million USD in 2014/15.32 In 2017-18, Nepal received 550 million USD from China which is 84% of the total FDI received.33 This shows a 500% hike in the Chinese investments in Nepal, which has provided China the required leverage with Nepal, to be used against India. Nepal’s act of pulling out of joint military exercise of BIMSTEC in 2018, on the insistence of China, is one such manifestation. China has invested heavily in Myanmar and Bangladesh, however, these two countries have taken the lessons from Sri Lanka and have become conservative with Chinese investments. Still China has been able to increase its leverage even with these two countries substantially in the last few years.

Conclusion

China is home to Sun Zu and has one of the longest traditions of strategic thinking. Sun Zu, in his ‘Art of War’, treats war as process of diplomacy; in essence war fighting is diplomacy by other means.34 Chinese have mastered the way economics can be used as one of most effective tools to achieve the national will. The ambitious Chinese dream of BRI being sold as ‘“shared growth through discussion and collaboration” is manifestation of the Chinese strategy to achieve the national will without fighting. The world is now taking cognizance of the ‘Shi’ factor in the great Chinese dream of BRI, and countries like Malaysia, Bangladesh and Myanmar have now shown reservation in accepting the Chinese bait of loans and have rejected or downscaled a few BRI projects.

References:

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War, translated by S.B. Griffith, Oxford: Clarendon press, 1964

- Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui Unrestricted Warfare.

- Study for Andy Marshall, Director Net Assessment, Office of Secretary of Defence, USA, available at https://cryptome.org/2014/06/prc-three-wars.pdf accessed on 13 Mar 19.

- Commodore Uday Bhaskar in China’s Three Warfare concept related to India and in Indian Ocean in Study for Andy Marshall, Director Net Assessment, Office of Secretary of Defence, USA, available at https://cryptome.org/2014/06/prc-three-wars.pdf accessed on 13 Mar 19.

- Keoni Everington in Chinese General lists 10 'privileges' Taiwan will 'enjoy' under 'one country, two systems' in Taiwan Times, Mar 5, 2019 available at https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3651302 accessed on 05 Mar 2019.

- Given in the script of the speech delivered by President Xi during the 19 Party Congress in Oct 17.

- Roberet D Blackwill & Jenifer M Harris in War By Other Means, in Chapter on Geo-economics in Chinese Foreign Policy, pp 95 , Pub by Harvard University press, London.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Christ Horton, in El Salvador Recognizes China in Blow to Taiwan, New York Time available on https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/21/world/asia/taiwan-el-salvador-diplomatic-ties.html

- Roberet D Blackwill & Jenifer M Harris in War By Other Means, in Chapter on Geo-economics in Chinese Foreign Policy, pp 95 , Pub by Harvard University press, London.

- The data taken from World’s Richest countries, targeted research on Taiwan Exports, available at http://www.worldsrichestcountries.com/top_taiwan_exports.html accessed on 05 Mar 2019

- Brahma Chellaney in China’s Weaponisation of Trade, in The Japan Times available at https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/07 accessed on 05 Mar 2019.

- Roberet D Blackwill & Jenifer M Harris in War By Other Means, in Chapter on Geo-economics in Chinese Foreign Policy, pp 95 , Pub by Harvard University press, London.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Brahma Chellaney in China’s Weaponisation of Trade, in The Japan Times available at https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/07 accessed on 08 Mar 2019.

- Andreas Fuchs and Nils-Hendrik Klann in Paying a visit: The Dalai Lama effect on international Trade, published in Journal of International Economics, available on https://www.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/docs/koenig-pamina/article_dalailama_effect_on_internationaltrade_jie_2013.pdf accessed on 08 Mar 19.

- China says hopes Mongolia learned lesson after Dalai Lama visit published in Reuters on Jan 24, 2107 available at https://in.reuters.com/article/us-china-mongolia-dalailama-idINKBN158197 accessed on 08 mar 2019.

- Staff research report of US-China Economic and Security Commission Report of 2017, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Report_China%27s%20Response%20to%20THAAD%20Deployment%20and%20its%20Implications.pdf accessed on 08 Mar 2019.

- Roberet D Blackwill & Jenifer M Harris in War By Other Means, in Chapter on Geo-economics in Chinese Foreign Policy, pp 95 , Pub by Harvard University press, London.

- Priyanka Kher and Trang Tran in discussion paper "Investment Protection Along Belt and Road' published by Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment (MTI) Global Practice for World Bank pp 30.

- Noah Barkin, Aleksandar Vasovic in Chinese 'highway to nowhere' haunts Montenegro published in Reuters available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-silkroad-europe-montenegro-insi/chinese-highway-to-nowhere-haunts-montenegro-idUSKBN1K60QX accessed on 11 Mar 19.

- Ibid.

- Maldives admits China interest in building port, in Maldives Times, available at https://maldivestimes.com/maldives-admits-china-interest-in-building-port-avas-mv/ accessed on 13 Mar 2019

- Panos Mourdoukoutas in “Modi Should Not Bail out China in Maldives”, in Forbes available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/panosmourdoukoutas/2018/11/28/modi-should-not-bail-out-china-in-maldives/#24784a9a41d8 accessed on 12 March 2019.

- China Wrestles with Chinese Corridor Debt in Nikkei Asia Review available at https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics-Economy/International-Relations/Pakistan-wrestles-with-growing-Chinese-corridor-debt accessed on 12 March 2019.

- Pakistan secures 6 billion USD aid package from Saudi Arabia, in Bloomberg available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-23/pakistan-says-saudi-arabia-agrees-to-6-billion-support-package accessed on 12 Mar 2019.

- The China-Maldives Connection, in The Diplomat available at https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/the-china-maldives-connection/ accessed on 13 Mar 19.

- Rajeshwari Rajagopalan in A New China Military Base in Pakistan? Published in Diplomat available at https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/a-new-china-military-base-in-pakistan/ accessed on 12 Mar 2019.

- Sushant Sarin, monograph on Corridor Calculus CPEC and China’s Comprador Investment Model in Pakistan, published by Vivekananda International Foundation.

- Prakash Bhandari in Growing Chinese Presence in Nepal, in Asia Dialogue available at http://theasiadialogue.com/2018/09/25/the-growing-chinese-presence-in-nepal/ accessed on 12 March 2019.

- China tops Nepal's foreign direct investment list for third consecutive year in Global Times, available at https://gbtimes.com/china-tops-nepals-foreign-direct-investment-list-for-third-consecutive-year accessed on 12 Mar 2109.

- David Lai, Learning from the stones: A GO approach to Mastering China’s Strategic Concept ‘Shi’, available at http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi accessed on 14 Mar 2109.

Image Source: https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/http://prod-upp-image-read.ft.com/01d1de4c-8f4c-11e8-bb8f-a6a2f7bca546?source=next&fit=scale-down&quality=highest&width=1440

A very well articulated and highly informative article. Thorough research and to the point narration brings forth the issue in a very impressive manner. A wonderful read.

Post new comment