Paradox of Peace in Kashmir

Chancellor Willy Brandt of Germany had said, “Peace is not everything, but without peace, everything is nothing”.1 Kashmir is passing through a similar situation where lack of peace has led to a collapse of societal values and parental control over children. Educational institutions and places of worship have become the hubs of radicalisation leading to disaffection among the citizenry with the state. To add fuel to fire, institutions of governance are fast becoming irrelevant and ineffective in restoring peace.

In the prevailing environment Kashmiriyat has been replaced by intolerance and space for accommodation and reconciliation has shrunk. Terrorism, drug trafficking and stone pelting have become an alternative way of life. Some youth in Kashmir openly say that stone pelting is the bread and butter of current generation, which ironically fits into the Jihadi discourse - with economic benefits. Desiderius Erasmus Adagio, a social scientist from the 15th century had said, “The most disadvantageous peace is better than the most just war”. There is interdependence between peace and development, and there can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development.2 If the state is unable to restore peace, its role gets marginalised because the inter-dependence between development and economic empowerment through peace is severed.

There are a growing number of people who are suggesting that the conflict in Kashmir is socio-political in nature and the endeavour of the government to resolve it through security forces is a tired strategy. But today this conflict has gone beyond the socio-political sphere and it is now non-linear in character. It is a war that is being driven by radical ideology, cross border terrorism, disaffected youth, war of perceptions and diverse political voices with little consensus on the end state. The idea of continuing this conflict is to make it unending and bleed India forever. Haseeb Drabu believes that while what happened in the 1990s was an "ethno-national movement", the genesis of the current turmoil is vastly different. "Today's strife," he says, "is almost anarchic.3 More than anything else, the anarchic environment that prevails in Kashmir has almost broken the social contract between people and the state. The reasons for this are the: erosion of cultural values; radicalisation; and the lack of parental control over the current young generation.

The strategy for peace building and conflict transformation requires civil society’s support. Even if the government strategy fails, strong societal pressure can prevail upon the disaffected youth and discontented voices. In the Northeast, the Naga Mothers Organisation has prevailed upon the rebels to join peace negotiations. The ‘Forum for Reconciliation’ in Nagaland has acted as a peace-maker whenever there is a threat of the re-emergence of violence in society. However, in Kashmir there is no such societal organisation that can bring all stakeholders to negotiating table. Those who endeavoured to become peace brokers were silenced by terror organisations. In Kashmir, peace will return only if there is close cooperation between civil society and independent experts.4 However, it is not happening because there is no organisation that can get the various stakeholders to come to the negotiating table. One of the primary reasons for the lack of a breakthrough out of this paradoxical situation is the absence of understanding of the concept of peace building.

The Jammu & Kashmir state has been suffering on account of the recurrence of conflict at periodic intervals. In the past, violence was brought within manageable limits but for some reason or another conflict continued to revive. This shows that state and society have lost the ability to prevent escalation and there is no cushioning to absorb this reversal. In such a situation the state must ensure that it does not give any leverage or handle to inimical forces to destabilise the situation all over again.

There is a need to understand that all activities aimed at peace building and conflict resolution, constitute political and societal interventions. Templated models often lead to a dead end over the long or short term.5 Successful conflict transformation takes place in the security, cultural and societal domains; it changes national narratives and mutual perceptions, and relations between society and the state. These are issues that require a profound understanding of the concept of peace enforcement and peacebuilding. Such initiatives cannot be undertaken in isolation. They form part of all the government initiatives. However, the Kashmir policy has seen security forces being used for conflict resolution and that is certainly not a good idea to pursue. It defies the basic tenets of the concept of conflict transformation and peace building.

Understanding the Concept of Peace in Kashmir

The concept of peace in a non-linear conflict such as Kashmir is different from that in the case of insurgency or public disorder. It is a nuanced and profound process that is expected to be understood by the policy makers and the political leadership. Why has peace collapsed even after security forces have restored a semblance of stability in Kashmir multiple times, since 1996? The reason is that it was an ‘enforced peace’ that is usually temporary in nature. An enforced peace, by and large, implies just a suppression of violence and not the elimination of violence. To consolidate the gains and prevent violence from recurring during the temporary peace, there is need to create conducive conditions by reviving the societal contract between the state and citizens.

Concurrently, there is a need to initiate political engagement and economic development to build up the capacity for peace building. When a state emerges from conflict and achieves adequate peace, it is an indication that all institutions have started functioning, and political initiative should then take the lead to establish an enduring peace. There should be no experimentation during the stages of temporary and adequate peace because the possibility of a relapse of conflict does exist. Conflict relapse took place in 2008, 2010, 2014 and 2016, because of triggers such as the pretext of the Amarnath land row, the Machil fake encounter and the raising of emotional issues such as Article 370 and 35 A.

Even in Nagaland it is difficult to say whether peace will endure, it is still only an adequate peace because the armed cadres are still intact and any trigger can lead to a relapse. The only saving grace in Nagaland is that social organisations have fair amount of control and influence over the population, and this often prevents the relapse into conflict so that the government and the dissenting groups remain engaged. Enduring peace is the final stage when the conflict has ended and grievances are addressed. However, experimentation during the initial phases of enduring peace should be resisted. Any issue that may disturb the peace process must not be raised. J&K is at the moment not ready to debate Article 370 or 35 A, which will only negate the gains made by the security forces. The political leadership and policy makers must understand these three stages before they make radical changes in governance or try to alter the historical status quo.

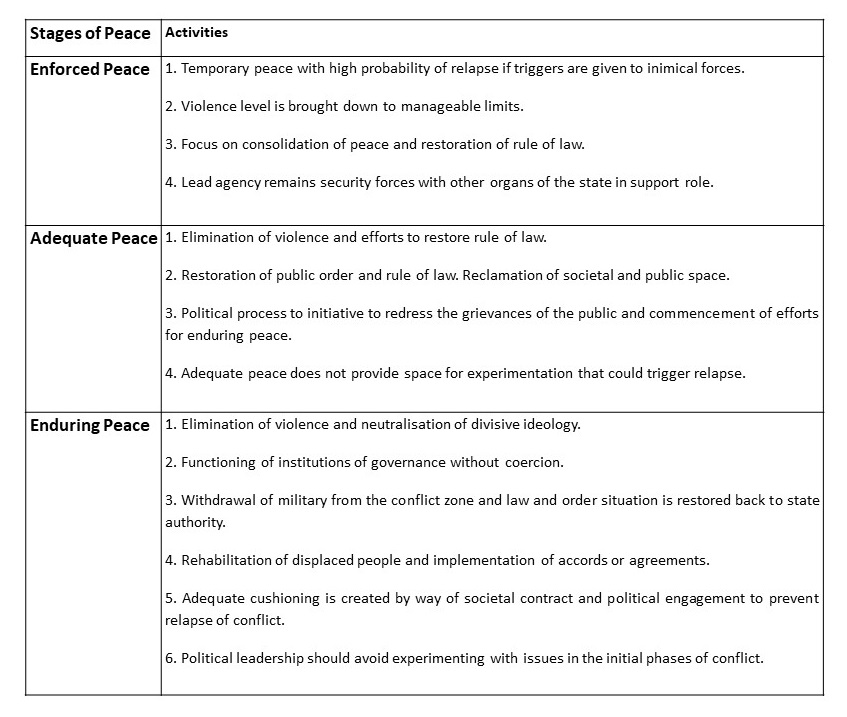

The suggested activities and concept of peace in a complex conflict such as Kashmir are as shown in the diagram below:-

Conclusion

Ronald Reagan had said, “Peace is not absence of conflict; it is the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means”. Even when armed conflicts end through military or negotiated means, the legacies of violent confrontation remain. These legacies include the atrophying of crucial social institutions, weak democratic regimes, corruption in the distribution of natural resources, and ongoing circulation of weapons and proliferation of crime.

In sum, conflicts have lasting negative impacts on society.6 It is important to make civil society a stakeholder in peace building and conflict transformation.7 There is a need for the political leadership and policy makers to understand the concept of peace and to create cushions to prevent a relapse into conflict.

End Notes:

- Federal Government of Germany, Guidelines on Preventing Crises, Resolving Conflicts, Building Peace, September 2017. p. 10.

- UN Chronicle, “The Legacies of Armed Conflict on Lasting Peace and Development in Latin America”, April 2016.

- Raj Chengappa, “What went wrong in Kashmir and how to fix it”, India Today, September 12, 2016.

- Edelgard Bulmahn, Hans-Joachim Giessmann, Marius Müller-Hennig, Mirko Schadewald & Andreas Wittkowsky, Cornerstones of a Strategy for Peace Building and Conflict Transformation, April 2013, p 19 at https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/09848-20140724.pdf ACCESSED December 21, 2018.

- Ibid.

- n 2.

- n 4.

Post new comment