The Central Statistics Office recently reported that the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth had slipped to a three-year low of 5.7 per cent for the April-June quarter of the current fiscal. This is in contrast to the preceding quarter growth of 6.1 per cent, and the figure is even worse when compared to the same quarter an year ago, of 7.9 per cent. It should have the Union Government worried, and it has. Union Minister for Finance Arun Jaitley said that the slump was a “matter of concern” and hinted that the slow pace in the manufacturing sector (the growth here has been at a poor 1.7 per cent) was primarily responsible for the dismal number. Chief Statistician of India TCA Anant voiced a similar opinion. By this latest data at least, India is no longer the world’s fastest growing economy; China, with 6.5 GDP growth, has forged ahead.

Will there be an early revival? The answer depends on where it is sought from. The opposition Congress sees little hope, with its spokesperson Manish Tewari claiming that the Indian economy had begun to “grow with the Modi rate of growth”, which is barely five per cent if you go by the 2004-05 base year”. He alleged that the Government had “lost the plot”. But the newly-appointed Vice Chairman of Niti Aayog Rajiv Kumar has an opposite perspective. Himself a noted economist with some understanding how the Government functions, Kumar expressed optimism of a turnaround, though he was unwilling to downplay the June-ending quarter figure. He added, “I am confident that in the July-September quarter, economy will grow by 7-7.5 per cent”. He placed his trust on two factors — greater clarity on and stabilisation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime, and a good monsoon. It is to be seen if a rejuvenation of the GDP growth can happen as early as the end of this September quarter, as Rajiv Kumar says. In any case, the Government will want the turnaround to happen sooner than later because it has the 2019 Lok Sabha election coming up in less than two years’ time. Long-term projections, howsoever rosy they may be, can hardly give electoral comfort to the Modi regime. Its flagship programmes such as Make in India, Startup India, Skill India and Digital India, the opening up of foreign direct investment potential in various sectors, and initiatives taken towards ease of doing business, are all designed to boost both growth and employment. Over the next decade, they do have the power to change the country’s economic paradigm — the way PV Narasimha Rao’s reforms did 25 years ago. But, politics and economics demand that more immediate results are made available.

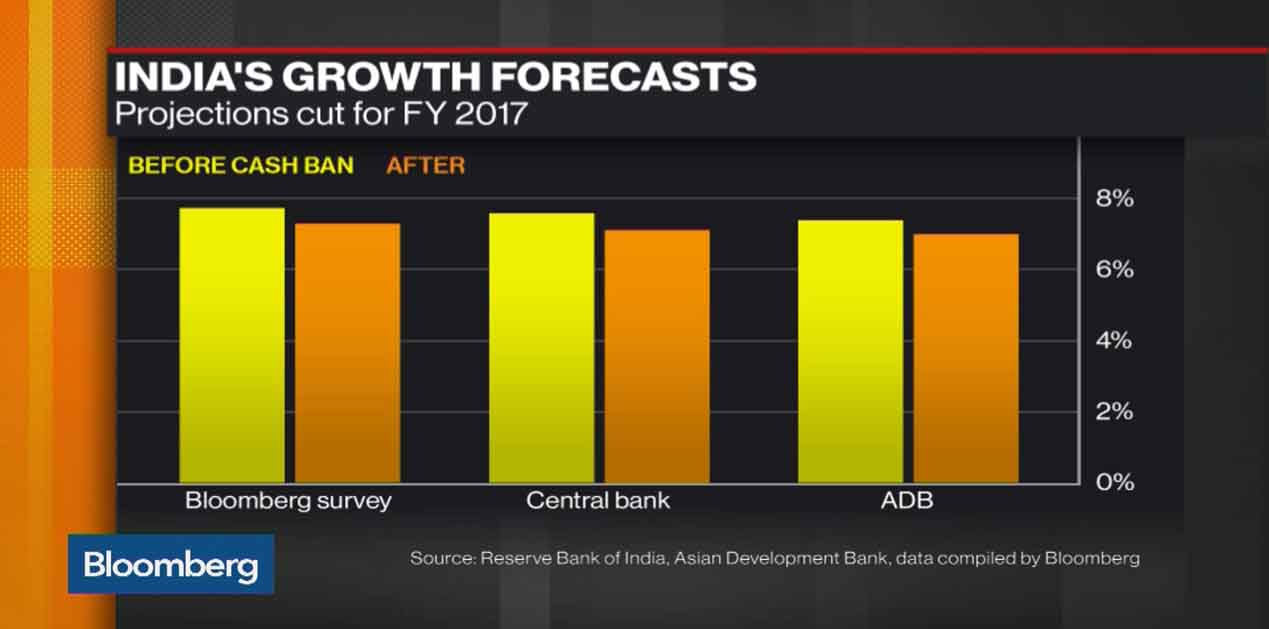

Interestingly, both the Government and the opposition parties have used last November’s demonetisation decision and the arrival of the GST system as a backdrop for the slowdown of growth, and both acknowledge that the two measures have had an enormous disruptive impact. With reports that 99 per cent of demonetised currency has returned to the banks, the Opposition is demanding to know where the black money component was, especially given that the Government had projected demonetisation as a frontal assault to flush out unaccounted wealth. More importantly, critics of the Modi regime point to the ‘damage’ that demonetisation has done to India’s economic growth — and without the resultant benefits the Government had claimed would accrue to offset the ‘temporary’ setback. The opposition parties have also accused the Centre of rushing into the GST regime without proper planning, and driving the economy to the edge. However, the Government has maintained that GST will turn out to be a huge plus factor in driving economic growth once the system settles down to a near glitch-free performance. On demonetisation, it has argued that massive amounts of hitherto unknown monies have joined the country’s banking system — which in itself is a big achievement. Besides, the inflow of funds has not just helped the banking sector but will also assist the tax authorities to trace questionable deposits in the months to come. In a related development, the Union Ministry of Finance has cracked down on 200,000 dormant companies, some of them suspected of money laundering and stock price manipulation. The Government has acknowledged the disruptive nature of both GST and demonetisation, but added that their adverse impact on economic growth was a short-term phenomenon. Incidentally, this view has been seconded by various economic experts, ranging from those at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, global credit rating agencies and commentators from within the country.

There is no doubt that demonetisation and GST have contributed to the slowdown of GDP growth, but it would perhaps be an exaggeration to hold them entirely responsible, or believe they are the key factors. The first full quarter after demonetisation was that of January-March 2017, and it was the period when the effects of the decision ought to have been at its worst. Yet, GDP growth remained healthy, and was actually at a decent 6.1 per cent in the quarter ending March 2017; it wasn’t bad in October-December 2016 either. The fallout must have waned by the April-June quarter, and, therefore, the blame lies not at demonetisation’s doors. Similarly, pre-GST disruptions, although admittedly serious, could not have been so impactful that they should drag the GDP growth so far down. Besides, one must not lose sight of the fact that the growth rate has been going down for the past six consecutive quarters — in March 2016 ending, it was 9.2 per cent; and then it went on a downward spiral to 7.9 per cent, 7.5 per cent, seven per cent, 6.1 per cent — and now 5.7 per cent. Clearly, there had to be other explanations, and finding scapegoats in demonetisation and GST makes no sense for either the Government or the Opposition.

It should not be too difficult for the Government to fix the problem because it has the intent, the talent and the right direction. Besides, India’s economic fundamentals are robust — inflation is hovering at about two per cent or less; trade and fiscal deficits are within manageable limits; foreign direct investment is at a high; domestic lending rates are down (though there is scope for more cuts and it’s a call which the Reserve Bank of India must take); and the Centre appears determined to tackle the non-performing assets issue plaguing largely the public sector banks. In other words, there is room for the Government to take bold initiatives to bring the GDP growth back on track. It needs to provide an immediate stimulus in targeted areas that result in both growth and employment. The latter is important from the Government’s perspective, given that it has faced accusations for failing to have triggered job growth. Conflicting figures have compounded the issue. According to data presented in the Lok Sabha in February this year, the country’s unemployment rate was 3.7 per cent. But a senior Minister, on the same day as the figures were made available in that House, said in the Rajya Sabha that the unemployment figure was five per cent — and rising. But of course the issue of unemployment is an old one and it would be unfair to hold the incumbent regime responsible for the mess. According to a Kotak Securities report, just seven million jobs had been created annually over the last 30 years, whereas the country needed 23 million jobs annually. Yet, there is no escaping the fact that the Modi Government, having promised to turn around the scenario, has to deliver more. It could revisit some of its initiatives, such as the Mudra scheme, which is designed to provide self-employment and resultant direct and indirect employment.

Undeniably, the manufacturing sector, apart from crore infrastructure, has the greatest potential for large-scale employment generation. Unfortunately, manufacturing is also the laggard in present times. The manufacturing sector growth at 1.2 per cent is the lowest in the last five years, and this is largely because private investments have failed to pick steam despite the Government’s various flagship programmes. The fall in the investment ratio over the last decade can be partly attributed to the global financial crisis of 2008. The ratio shows a steep fall from 38 per cent in 2007 to around 30 per cent towards the end of 2016. Private investment declined 19.2 per cent in 2011-12 to 16.8 per cent in 2014-15. Corporate sector investments dipped from 16 per cent to around 10 per cent in 2016. This has been attributed to increasing debt burden and a slowdown in private credit due to stressed assets in banks etc. These in turn have led to an increase in stalled projects — though it must be emphasised that projects were also stalled due to bureaucratic delays and other reasons such as non-availability of land and payment issues. Whatever the reasons, the delays in completion accounted for six to seven per cent of the GDP and crippled the growth momentum.

The Index of Industrial Production (IIP) data also tell a story. According to the Central Statistics Office, the cumulative industrial growth during April 2016-February 2017, as compared to the corresponding period of the previous year, was 0.4 per cent. Fifteen out of 22 industry groups in the manufacturing sector showed negative growth during February 2017, as compared to the same month of 2016. It is, then, obvious that the manufacturing sector, hobbled by lack of private investment, has failed to click. Equally obvious is the fact that the Government’s various measures and its repeated appeals for private investments, have not worked. The private sector’s attitude is baffling. The Government has gone a long way in addressing many of its concerns. It has reduced red tape, streamlined rules and regulations for business, brought in the bankruptcy code, done away with quite a few of the archaic laws that stifled industry, and in general created an investor-friendly environment. True, there are issues still, one prominent among them being the unchanged labour laws. But there has never been an ideal situation and there never will be, for private investment. Over the last decade, however, this is the best time, and yet the private industry has simply not shown the zeal to seize the moment.

If private manufacturing has been sluggish, the export sector’s performance too has been dismal, and this has contributed to low GDP growth in some ways. It’s not a coincidence that over the last decade and half or so, a high GDP growth came alongside booming exports. The near eight per cent growth during 2003-11 was complemented with a 20 per cent growth in exports. Exports were close to $319 billion in 2013-14; they were down to $274 billion (and this was an ‘improved’ figure as compared to 2014-15). It can be argued that export statistics are dependent almost entirely on the state of the world economy and also on the currency rates. The 2008 crisis, starting with the subprime issue in the United States of America and spreading across the globe, chipped off many millions of dollars from exports of many nations, India included. It has taken almost a decade for the global economy to find its feet again, but it remains to be seen whether India can quickly enough do so. On the currency matter, it must be accepted that the real effective exchange rate (REER), which is the exchange rate after adjusting for inflation, has seen a sharp rise over the years, thus rendering exports uncompetitive. The rise in the REER index has coincided with the sharp drop in export revenues. That said, it would be naive to believe that exports have done less than expected merely on grounds of global economic downslide and rising REER. There are other factors as well, including the uncompetitive costs of production and accompanying logistics (freight rates, for instance).

Given the situation, there is clamour from the Opposition camp that the Government must course-correct. This is true, but the course-correction must not be in the direction which the critics want the regime to take. Straying from the reform path would be bad, and returning to the so-called socialist economy would be disastrous. There is a lot that the Government must push for — a new land acquisition law and comprehensive labour law reforms, for instance. Additionally, it should continue to work on ease of doing business by further simplifying rules without diluting accountability. The Government must resolve the banking sector’s non-performing assets conundrum. And, since incremental measures haven’t had the desired impact, perhaps it’s time for some bold and out-of-the-box solutions.

It’s easy for a Government with a dominant majority in the Lok Sabha to become complacent and populist, especially when polls are two years away. But it’s also easy for such a regime to bite the bullet. The Modi dispensation must remember that the people have backed it on bold decisions such as demonetisation, and there is no reason why they will not do so again, if strong and non-populist measures are taken to enhance growth and employment.

(The writer is senior political commentator and public affairs analyst)

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-02-28/bouncing-back-from-cash-ban-india-chasing-v-shaped-recovery

Post new comment