Left Wing Extremism (LWE) is widely recognised as one of the most serious security threats in post-independence India. Apart from that, it is also a politico-socio-economic challenge. Former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh had described the LWE as “India’s biggest internal security challenge ever” (Akhoury 2006). Recognising the LWE movement as a serious problem, Prime Minister (PM) Modi urged the extremists to “shun the gun for a few days and visit the families affected by their violence … Those children would certainly inspire misguided youth to lay down arms forever…This experiment will force you to change your heart and make you shun your violent means”. He further asked the administration to “Stop the spread of Left Wing Extremism in the country”, with the Ministry of Tribal Affairs playing a key role in this regard (Press Trust of India 2015). The PM specifically pushed for ‘technology penetration’ to ensure that the “undeveloped tribal areas are connected with developed areas through good infrastructure to bring some relief in LWE region”

As it began in 1967, LWE was limited to the three police station areas namely Naxalbari, Khoribari and Phansidewa of Darjeeling district in West Bengal. However, in recent years, the movement has assumed alarming proportions, threatening peace and security over a vast stretch of land spreading across 10 states, described as the ‘Red Corridor’. The history of LWE movement, which dates back across 50 years, has survived on some basic issues like poverty, disparity, and discontent among the masses. It is a common phenomenon worldwide, but its intensity is high in developing countries in particular.

The Maoist insurgency doctrine, as elicited from copious documents recovered from their hideouts during several raids and encounters, is based on the glorification of the extreme left ideology. It legitimises the use of violence to overwhelm the existing socio-economic and political structure. Based on this ideology, People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army was created as an armed wing of the Communist Party of India – Maoists (CPI-M). The movement got strengthened in 2004 with the merger of People’s War Group (PWG) that was influential in Andhra Pradesh, the Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI) with a stronghold in the central Indian states and the CPI-M (Oetken 2008). This merger significantly upgraded the combat capabilities of LWE groups together.

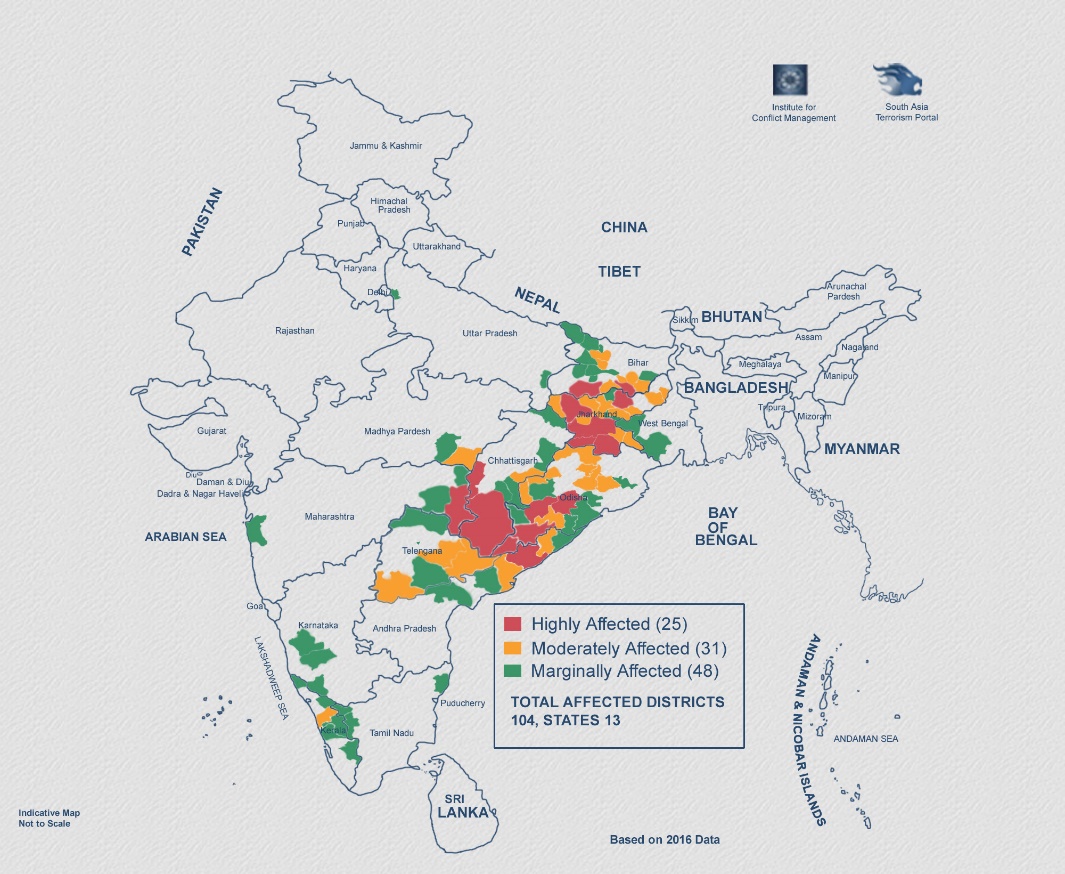

Over the decades since, the LWE movement is assessed to have impacted 40 percent of India’s territory and 35 percent of its population (Morrison 2012). In 2016, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), 106 districts in 10 states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, were intensely affected by the LWE movement (M. P. Government of India, LWE affected districts 2016). Based on the intensity of insurgency, 35 of the 108 districts spread over the ten States mentioned above, have been classified as most affected LWE districts. The States of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Bihar are considered severely affected. The States of West Bengal, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana are considered partially affected. And the States of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh are considered slightly affected. Currently, the lethality of the LWE movement has increased multi-fold, establishing a complex web across the 10 states of India. It is estimated that these extremist outfits now have around 9,000-10,000 armed fighters with access to about 6,500 firearms. In addition, there are estimates of about 40,000 full-time cadres (L. M. Government of India 2017).

Courtesy – South Asian Terrorism Portal - http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/database/conflictmap.htm

Over the years, a paradigm shift has been observed in the tactical capabilities of LWE groups from traditional bow and arrows and country-made firearms of the 1960’s, to the Light Machine Guns (LMG), Self-Loading and AK series Rifles, mortars, and rocket launchers in 2017. The extensive use of Landmines and Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) against security convoys, police stations, and railways highlight the Maoists’ hi-tech weapon capabilities which make LWE a major challenge to the internal security of India. Over the last couple of decades, LWE violence has figured prominently in insurgency and terrorism-related violence in India. These incidents include intimidation, killings of innocent civilians, abduction, extortion, IED blasts and ambush attacks on the security forces personnel etc. At certain remote locations, it is acknowledged by several government officials that Maoists collect taxes and dispense brutal and instant justice through kangaroo courts called Jan Adalats. One of the principle reasons for the rapid growth of LWE across the country is cleaver exploitation of the real or perceived socio-economic grievances of the poor and the oppressed, mostly belonging to the tribal population. It must however be noted that none of the LWE organisations have done anything to ameliorate the condition of the tribals whose plight it pretends to be fighting against. Rather, the movement has been more of a hindrance to the development initiatives of the state which were designed to address those very issues.

The core objective of the LWE movement is the establishment of People’s Revolutionary State, which is supposed to be achieved by establishing a ‘Red Corridor’, stretching from the Nepal border through Central India till Karnataka in the South (Mitra and Dutt 2016). This objective is to be achieved by using armed struggle as the prime tool to garner the support of the oppressed and the exploited. Violent protracted struggle is therefore expected to continue to help the movement consolidate and extend the Corridor. Naxal leaders support various issues like protecting people’s rights of Jal (water), Jungle (Forest) and Jamin (Land) (JJJ) (P. M. Government of India 2014). These are prominent concerns of the people mainly in the rural India as most of the people depend on agriculture and forest for their livelihood. Thus, any threat to these three elements is seen as a threat to their livelihood and triggers a high level of anxiety. In addition to the building up an effective web of armed operatives to spread terror, Naxals also recruit influential local tribal leaders to maintain their firm grip over villagers in remote locations, like in the dense forests of Chhattisgarh and eastern states of India. All available literature on the Maoist movement including their internal policy papers, confirm this assessment.

Most of the LWE affected areas are rich in mineral resources which are vital for the Indian economy. It may be noted that of the total power generation in the country, 75 percent comes from thermal based coal-fired power plants and five of the LWE affected states provide 85 percent of country’s coal (M. Government of India 2014). Apart from coal, the region is also important due to ample availability of other critical resources like copper, nickel, bauxite, manganese, iron, etc. But presence of LWE in the region adversely impacts commercial viability of any major investments in the mining sector. Naxals either obstruct inflow of developmental investments in the region or try to extort money from the companies. For example, for exploitation of mineral wealth in Chhattisgarh, the government has approved several investment agreements with major corporate houses. But these initiatives have met with strong opposition from the tribals (S. Banerjee 2008). Thus, it is imperative for the government to eradicate LWE and create conditions for secure investment and un-interrupted mining activities. This will generate employment in the region and will address issues of poverty and the perceived exclusion. Achieving the developmental goals will help in winning hearts and minds of the local people.

A noticeable trend in Naxal (LWE) violence in recent times is their resorting to high profile and high impact terror attacks. A few examples of such high impact incidents were: the April 06, 2010 attack in Tadmetla where Maoists killed 76 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel; the June 29, 2010 incident at Dhaurai in Narayanpur in which 26 Jawans were killed; May 25, 2013, attack at Darbha Ghati in which 27 people, including CRPF personnel and political leaders, were killed (Ghose 2017). Recently, a major attack took place on March 11, 2017, when Naxals ambushed a patrol party of CRPF, killing two CRPF Jawans (PTI 2017).

Amongst the major Left Wing Extremist groups, CPI (Maoist) continues to be the most active outfit and accounts for more than 80 percent of total LWE violence. The Dantewada incident of April 06, 2010 marks the efforts made by CPI-M to revive erstwhile strongholds along the inter-state border region of various states of the ‘Dandakaranya’1 region (Deshpande 2010). This tactical measure by Maoists was intended to divert the attention of the security forces from its core areas of operation in the central region of India. However, revival efforts by Maoists in the border areas of Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, establishment of a base at the tri-junction of Kerala-Karnataka-Tamil Nadu, and formation of a new Zone at the tri-junction of Madhya Pradesh-Maharashtra-Chhattisgarh, did not meet the desired success due to periodic interdictions of senior leaders by the security forces (M. Government of India, Internal Security 2017).

Present Status

The MHA data (April 2017) reveals that there was a significant rise, by 24.56 percent over the previous year, in the civilian fatalities in LWE violence in 2016. One of the reasons for the high rate of civilian fatalities is the LWE action against local citizens, who help the security forces by providing information against Maoists. The MHA report also affirms that in 2016 there was an increase by 50 percent in the number of encounters between the Naxals and the security forces and an unprecedented 122 percent rise in the elimination of armed Maoists cadre. It is reported that 222 LWE cadres were eliminated and 1840 arrested in 2016 (M. Government of India 2017). This is reflective of the well-coordinated operations conducted by the security forces deployed in the region.

The trend analysis of the Naxal movement from 2010 till 2017 suggests that Maoists are strengthening coordination efforts between their parent organisation CPI-M and other like-minded organisations to undertake programs against alleged ‘state violence’ and for ‘protection of their democratic rights’. For example, the issue of displacement of local communities remained the main plank of mobilisation by their front organisations like Niyamgiri Suraksha Samitee actively agitating in the Niyamgiri Hills area and Jharkhand Visthapan Virodhi Jan Vikas Andolan, a front of CPI (Maoists), protesting against amendments to the Chhotanagpur (1908) and Santhal Pargana Tenancy Acts (1949). These amendments pertained to the modifications in the Domicile Policy. Maoist affiliates also undertook protests and resorted to anti-government propaganda over alleged atrocities by the Security Forces. They organized similar meetings over the issue of Kashmir and called for a plebiscite in the State (M. Government of India, Internal Security 2017).

Government’s Approach

The Government of India has adopted a holistic approach to address the LWE insurgency. This approach is built around simultaneous implementation of a security agenda, developmental activities and promotion of good governance. The National Policy and Action Plan to address LWE problem, formulated by the MHA in 2014, essentially incorporates four elements - an integrated multi-pronged strategy comprising security related measures; development related initiatives, ensuring rights and entitlement related measures, and management of public perception (M. Government of India 2017). Under the plan, the Central Government has been implementing various flagship developmental schemes in coordination with the affected state governments. Some of the prominent schemes are: The ‘Integrated Action Plan’ (IAP) or ‘Additional Central Assistance’ (ACA) for LWE affected districts for creating public infrastructures and services in affected areas; ‘Road Requirement Plan–I’ (RRP– I) for improving road connectivity in 34 LWE affected districts; skill Development in 34 Districts of LWE under the ‘Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojna’ (PMKVY); ‘Fortified Police Stations’ by construction and strengthening of 400 police stations in 10 LWE affected states; and installation of mobile towers in the affected states for better communication connectivity.

Government of India has also accepted the suggestions of the 14th Finance Commission and enhanced the net proceeds of Union Taxes to the States from 32 percent to 42 percent. Consequently, some schemes run in LWE affected States have been de-linked from central assistance and transferred to the respective States. It will give the states sufficient flexibility to conceive as well as implement schemes suited to local needs and aspirations. It will strengthen the roots of governance and subsequently bridge the developmental deficit in the remote regions within LWE affected states. This developmental outreach by the Government of India has seen an increasingly large number of LWE cadres shunning the path of violence and returning to the mainstream. The table below endorses this claim:-

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of LWE cadres surrendered in country | 265 | 394 | 445 | 282 | 676 | 570 | 1442 |

'Police' and 'Public Order' being State subjects, maintenance of law and order lies primarily in the domain of the State Governments. The Central Government closely monitors the situation and supplements and coordinates their efforts in several ways. These initiatives include providing Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs) and Commando Battalions for Resolute Action (CoBRA); sanctioning of India Reserve Battalions (IRB); setting up of Counter Insurgency and Anti-Terrorism (CIAT) Schools; modernising and upgrading State Police and their intelligence apparatus under the ‘Scheme for Modernisation of State Police Forces’ (MPF scheme); reimbursing security expenditure under the ‘Security Related Expenditure’ (SRE) Scheme; filling up critical infrastructure gaps under the ‘Scheme for Special Infrastructure’ in LWE affected States; providing helicopters for anti-Naxal operations, providing assistance in training of state police through the Ministry of Defence, the central police organisations and the Bureau of Police Research and Development; sharing of Intelligence; facilitating inter-State coordination; extending assistance in community policing and civic action programmes etc. The underlying philosophy is to enhance the capacity of the State Governments to tackle the Maoist menace in a concerted manner. The concerned Division in MHA also monitors the implementation of Integrated Action Plan for LWE affected Districts (now called Additional Central Assistance to LWE affected districts) and various other development and infrastructure initiatives of the Government of India (L. M. Government of India 2017).

In coordination with the developmental outreach of the government, the Security Forces (SF) have continued to strengthen their position in the fight against LWE. According to MHA data, the kill ratio in 2016 stood at 1:3.41 in favour of the SF, more than double the ratio in 2015 (1:1.50). At its worst, the ratio had dropped to 1:0.59 in 2007. The number of encounters has also increased from 247 in 2015 to 328 in 2016, clearly indicating more aggressive approach of the SF on the ground. On the other hand, during the same period, the number of attacks carried out by the Maoists on SF did not witness any significant decline, marginally coming down from 118 in 2015 to 111 in 2016. However, incidents of snatching of arms from the SF came down substantially from 18 in 2015 to just three in 2016. SF recovered 800 arms in 2016 in addition to 724 in 2015. 1,840 Maoists were arrested through 2016, in addition to 1,668 arrests in 2015. Sustained SF pressure also resulted in a significant surge in the number of Maoist surrenders, which increased from 570 in 2015 to 1,442 in 2016 (South Asia Terrorism Portal 2017).

Solution SAMADHAN

During the recent review meeting of the Chief Ministers of the LWE affected States on May 08, 2017, the Union Home Minister enunciated an integrated strategy through which the LWE can be countered with full force and competence. The new strategy is called Samadhan, which is a compilation of short term and long term policies formulated at different levels. The meaning was well defined by the Home Minister as:

1. S- Smart Leadership

2. A- Aggressive Strategy

3. M- Motivation and Training

4. A- Actionable Intelligence

5. D- Dashboard Based KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas)

6. H- Harnessing Technology

7. A- Action plan for each Theatre

8. N- No access to Financing

In doing so, the Home Minister reassured the states about the consistent security-related assistance by the Union government. He mentioned that under the program of assistance 118 Battalions of CAPF have been deployed in the States. Besides, States have been given sanction for IRBs and Special IRBs to strengthen the security apparatus of the States. In addition to this, 10 COBRA battalions have been deployed to handle LWE issues. In the last few years, the MHA has assisted the States through various schemes for capacity building. Under the SRE Scheme, reimbursement of security-related expenses, such as ex-gratia payments, transportation, training, honorarium for Special Police Officers (SPO) etc., were borne by the Central Government. In the financial year 2016-17, the Home Ministry reimbursed Rs 210 crores on this account (M. P. Government of India 2017).

Challenges Ahead

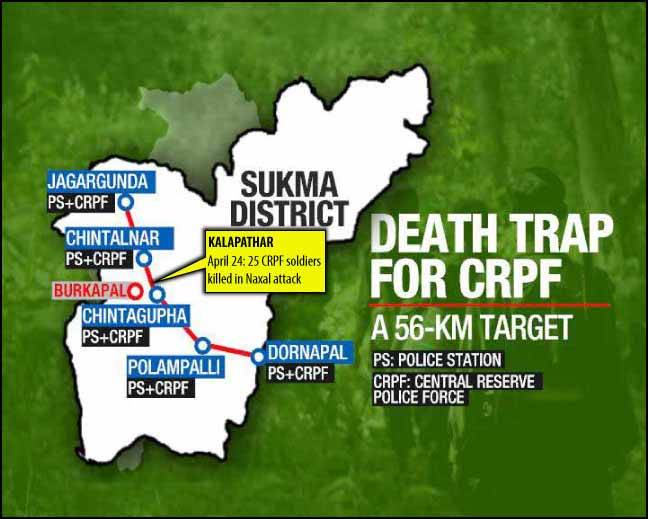

The above mentioned pro-active measures are introduced by the MHA which is also a nodal ministry pertaining to the LWE issues. However, there remain certain prominent issues, which have to be addressed. The recent Sukma attack of April 24, 2017 revealed the lack of preparedness on the part of the CAPF and the State Police. It also underscored a sequence of neglect of certain basic lessons of the past, as similar incident had taken place on March 11, 2017 in which 12 CRPF Jawans were ambushed by the Naxals.

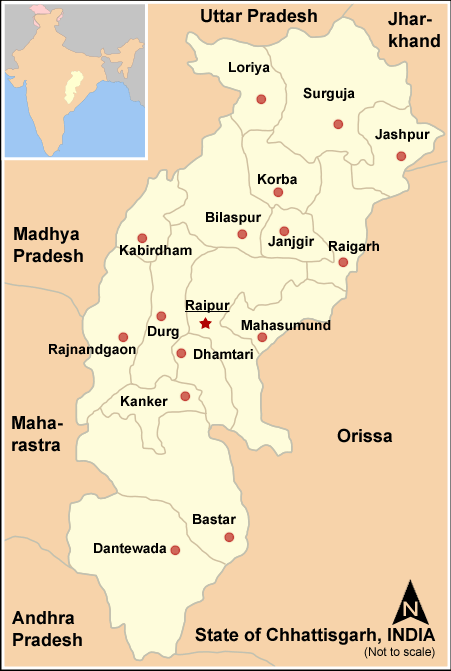

Chhattisgarh remains the worst affected state by LWE violence even though it has nearly 30,000 police personnel trained at the Counter-insurgency and Jungle Warfare College at Kanker and another 20,000 trained at the four Counter Insurgency and Anti-Terrorist Schools in the State. Despite this, analysts believe that the operational footprint of this large trained force is barely visible on the ground. It is CRPF that appears to be leading all operations in the worst-affected areas. One of the major operational drawbacks for the CRPF is its non-regimented approach of deployment which leads to the irrational deployments of CRPF personnel in passive defense. This means that the offensive operations by the CRPF is a rare phenomenon in Chhattisgarh as well as in other LWE affected states where troops remained confined to a ‘safe zone’ of nearly two kilometers around their camps. This is in contrast to the concept of area domination which is a basic prerequisite for physical safeguarding of any territory. Training wise, CRPF personnel deployed in anti-Naxal operations are not specialists in this field and not trained by the Army. Thus it is high time for the CRPF deployed in LWE region to have a regimented approach in operations and an overhaul of training and capacity development of its personnel (Sahni 2017).

Courtesy – India Today - http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/from-dantewada-to-sukma-naxal-attack-narrative-has-not-changed-in-seven-years/1/937882.html

The history of Counter-insurgency operations in India strongly suggests that the state police-led responses have always been more effective and successful. Punjab is a classic example in this regard. The reason is that the state police have greater familiarity with the local terrain, the causes, leaders and individuals involved, and have continuous interface with the population. This helps them to gather credible intelligence which is critical for targeted operations in the difficult terrains like LWE affected states. It also results in minimal collateral damage and maximum damage to the insurgents. It is therefore of paramount importance for the LWE affected states to shoulder greater responsibility, emerge as the principal counter-insurgency force in the state, and introduce necessary transformation in terms of leadership, well-defined mandate and strengthened capacity to produce enduring results.

The recent ambush of CRPF personnel in Chhattisgarh highlights the immediate need for the Indian State to adapt to both security and development issues of the LWE affected region. History of counter-insurgency in India suggests that a comprehensive counter-insurgency strategy must evolve continuously. Development, improved governance, and the ability of states to follow successful precedents are the prerequisites for the nation to look towards an assured future. It therefore is high time for the Government of India to revisit its central and state internal security policies.

Success of Andhra Pradesh against LWE provides an example for the Government of India and other LWE affected State Governments. A comprehensive approach adopted by this State, commonly described as the “Andhra Model”, achieved commendable success in pacifying the affected areas. It transformed Andhra Pradesh from a worst LWE affected State to a least affected one. The basic course of action was guided by vision, mission orientation, passion, and self-belief, duly backed up with quality training, and capacity and capabilities development, to transform the State’s counter-terrorism force, the ‘Greyhounds’, into a model for others to emulate. However, it is widely agreed that the LWE phenomenon in the currently affected states is well past the stage in which the ‘Andhra Model’ had worked; it would not work now. It is here that the newly envisaged approach, articulated under Samadhan, comes in as a positive initiative to deal with the challenge of LWE. The Government would be looking at this new approach to achieve good results, as it With its thrust on ‘Key Performance Indicators’ (KPIs) and ‘Key Result Areas’ (KRAs), Samadhan would enable smarter leadership and facilitate the application of ‘A’ or the Aggressive Strategy.

Endnotes

1 Dandkaranya geographical region roughly equivalent to the Bastar division of Chhattisgarh State of India. It encompasses 92,220 sq. km of land which includes Abhujhmar Hills in the West and Eastern Ghats in the East from the states like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Odisha. It spans 300 km from North to South and about 500 km from East to West.

References

Akhoury, Nishant. "Naxalism is gravest internal threat: PM." Times of India, April 13, 2006.

Banerjee, Sukanya. "Mercury Rising: India’s Looming Red Corridor." South Asia Monitor (Center for Strategic and International Studies), October 2008: 3.

Banerjee, Sumanta. "Naxalbari: Between Past and Future ." Economic and Political Weekly 37, no. 22 (June 2007): 2115-21116.

Deshpande, Rajeev. "Dantewada massacre: CRPF men fought till bullets ran out." Times of India, April 10, 2010.

Ghose, Debobrat. "Sukma Maoist attack: Intelligence, SOP failures led to massacre that killed 25 CRPF jawans in Chhattisgarh." First post, June 21, 2017.

Government of India, Left Wing Extremism Division Ministry of Home Affairs. "About the Division." http://mha.nic.in. June 10, 2017. http://mha.nic.in/naxal_new (accessed June 19, 2017).

Government of India, Ministry of Coal. "Coal Reserves." http://coal.nic.in. April 01, 2014. http://coal.nic.in/content/coal-reserves (accessed June 1, 2017).

Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Annual Report 2016-2017. Annual Report, Left Wing Extremism Division, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi: April 2017, 3-7.

The government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs Press Information Bureau. "LWE affected districts ." http://pib.nic.in. February 24, 2016. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=136706 (accessed June 19, 2017).

—. "Union Home Minister addresses the Review Meeting of Left Wing Extremism affected States ." http://pib.nic.in. May 08, 2017. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=161625 (accessed June 18, 2017).

The Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. "State Wise Extent of LWE violence during 2011 to 2017." http://mha1.nic.in. June 19, 2017. http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/LWE_period_19062017%20.PDF (accessed June 21, 2017).

—. "UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3749: Rajya Sabha." http://mha1.nic.in. April 05, 2017. http://mha1.nic.in/par2013/par2017-pdfs/rs-050417/3749.pdf (accessed June 19, 2017).

The Government of India, Press Information Bureau Ministry of Home Affairs. "Left Wing Extremism discussed in the consultative committee meeting ." http://pib.nic.in.November 12, 2014. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=111325 (accessed June 12, 2017).

Mitra, Subrata, and Rinisha Dutt. "India at Crossroads: Beyond the Dilemma of Democratic Land Reforms." ISAS working paper (Institute for South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore), November 2016: 26.

Morrison, Chas. "Grievance, Mobilisation and State Response: An examination of the Naxalite Insurgency in India ." Journal of Conflict Transformation and Security 2, no. 1 (April 2012): 55.

Oetken, Jennifer L. "Counterinsurgency against Naxalites in India." Chap. 8 in India and Counterinsurgency: Lessons Learned, by Sumeet Ganguly and David P. Fidler, edited by Sumeet Ganguly and David P. Fidler, 129. Oxon: Routledge, 2008.

Press Trust of India. "PM Narendra Modi asks ministries, NITI Aayog to frame strategies for tribal areas." The Indian Express, January 21, 2015.

PTI. "Chhattisgarh: 12 CRPF personnel killed in theNaxal attack." Indian Express, March 11, 2017.

Sahni, Ajai. "The crisis ailing the CRPF: Sukma attack won’t be the last if paramilitary training doesn’t match counter-insurgency goals." Hindustan Times, May 12, 2017.

South Asia Terrorism Portal. "India-Maoist Assesment 2017." http://www.satp.org. 2017. http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/Assessment/2017/indiamaoistassesment2017.htm (accessed June 19, 2017).

Image Source: http://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2017/jun/25/naxal-killed-four-security-personnel-hurt-in-separate-incidents-at-chhattisgarh-1620825.html

Post new comment