The Gwadar Port

The port of Gwadar has been a prominent part of Pakistani aspirations and also figures in many arguments about Chinese ambitions in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Gwadar has also been projected as the gateway of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to the Indian Ocean and beyond. The first manifestation of these aspirations was evident with the recent ‘opening’ or rather ‘re-opening’ of the Gwadar port wherein two ships sailed with a consignment of Chinese and Pakistani cargo for the Middle East and Africa1. The ships were escorted by the Pakistan Navy (PN) in their outward transit from the port. The Pakistani Navy has also announced plans for creating a naval force for the ‘seaward security of Gwadar port and protection of associated sea lanes against both conventional and non-traditional threats’2.

Report of possible Chinese naval participation with the PN for safeguarding the port have also surfaced which is a cause of serious concern for the region3. The Chinese, in their usual vein, have neither confirmed nor denied these reports with Colonel Yang Yujun, spokesman for the Ministry of National Defense (MND) of the People's Republic of China (PRC), sidetracking the issue4. Past Chinese official statements concerning the development of their military base at Djibouti were also on similar lines prior to the commencement of construction of the base and hence their official statements do not hold much water with actual developments on the ground being better indicators. All the same, this is a disturbing development which can have a destabilizing effect to the security of the region, especially given Pakistan’s penchant to leverage such situations.

Location of Gwadar

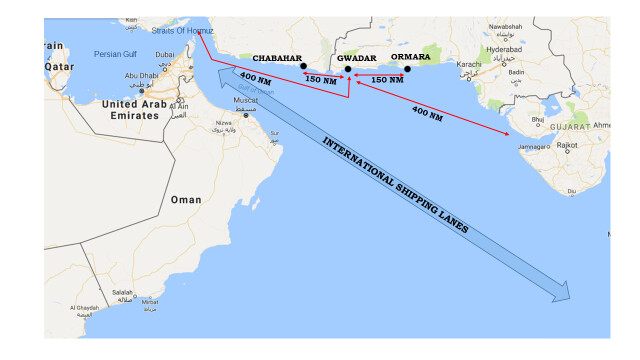

Gwadar is located in Balochistan on the Makran coast of Pakistan. The Straits of Hormuz, the vital waterway for the Persian Gulf, are just 400 nm (720 km) from Gwadar which gives it an enviable location astride the sea lanes emanating from this globally important straits. It is this location that Pakistan has attempted to capitalize on in the past, though without much success, primarily because of its inability to solve the basic problems of connectivity and governance in the region. The remoteness of this region from the rest of Pakistan and an incipient insurgency in Balochistan has hindered development of Gwadar till date. The absence of overland connectivity to the hinterland has also been a severe impediment in its progress though Pakistan has intermittently announced plans for creation of roads in the past.

Figure 1: Gwadar in the Northern IOR

The Iranian port of Chabahar, being developed by India, is located about 150 nm (230 km) to the west. The Jinnah Naval Base (JNB) at Ormara is located about 150 nm (230 km) to the east, which has been developed by the PN as an alternate base for Karachi and is intended for berthing its ships and future submarines. The current Chinese focus on Gwadar also stems from the attractiveness of its location which can serve to further Chinese strategic interests in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) as China tries to fulfill its dream of becoming a maritime power. The map below illustrates the strategic location of Gwadar in the Northern IOR.

Chinese Interests in the IOR

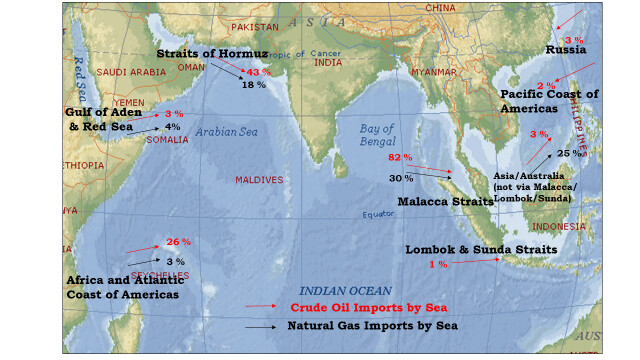

Energy Supplies. China’s energy needs are expected to increase exponentially in the coming decades with forecasts predicting doubling of this consumption in the next three decades. China depends largely on the Middle East, South and Central America, West Africa and the former USSR for its energy supplies. A large part, to the extent of about 75 – 80% of China’s oil imports transit through the waters of the Indian Ocean while another large chunk of about 10 – 15 % transit the Pacific Ocean. The remainder is imported through pipelines

Fig 2: China’s Energy Flows5

on land which is not very significant. The sea routes for transportation of oil through the Indian Ocean lie in waters where China does not have the required naval presence to deter potential threats. The Chinese are naturally concerned with this vulnerability and hence this issue finds frequent mention in their military strategy as also in various writings in this field6. The map below illustrates this criticality in China’s energy matrix.

Anti-Piracy Deployments. China has been a part of the anti-piracy effort since 2008 and has been sending ships for escorting merchantmen through the Gulf of Aden in the International Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC). It has, till date, despatched 78 ships and completed more than 1000 escort missions7. Though the number of pirate attacks has reduced to single figures in the last year, the international anti-piracy effort is likely to continue into the near future8. Hence the Chinese anti-piracy missions will also continue well into the future.

Commercial Interests. China has been consistently increasing its overseas commercial interests in the last ten years. It has increased its Outward Foreign Direct Investments (OFDI) from about $ 3 billion in 2005 to about $102.9 billion in 20149. A large chunk of China’s OFDI is concentrated in Asia and Africa. Apart from this, China is also partnering various countries of the Indian Ocean littoral in development of large infrastructure projects like the CPEC, China – Myanmar gas pipeline and port development projects in the IOR. Trade with ASEAN and South and West Asian countries has also been growing at a faster rate than that with other countries10.

Fears of American and Indian Intervention. The Chinese view the US ‘Pivot/Re-balance’ to Asia-Pacific as a “strategy targeted at China (which) has resulted in its endless moves aimed at building a circle of containment around China” 11. China also perceives India as attempting to control the Indian Ocean and hence is inimical to its interests in the IOR. Some Chinese strategists like Zhang Ming believe that “the Indian subcontinent is akin to a massive triangle reaching into the heart of the Indian Ocean, benefitting any from there who seek to control the Indian Ocean” 12. This perception is further reinforced by the wariness that India displays in its relations with China, which itself is a result of persistent suspicion about Chinese intentions. India’s expanding navy and its increasingly frequent presence in South East Asia and recent forays into the Pacific has further served to raise Chinese concerns.

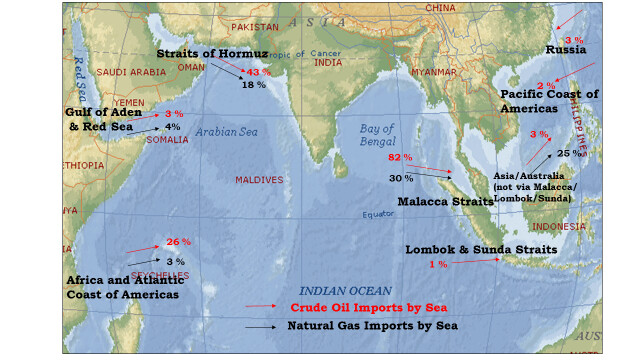

Chinese Arms Sales. China has become the third largest exporter of military equipment worldwide and many countries of the IOR have been some of the largest recipients in recent years. Pakistan, China’s traditional ally, has

Fig 3: Chinese Arms Sales in IOR

acquired frigates and corvettes and is jointly developing and marketing a fighter aircraft, the JF-17. It is also in the process of acquiring submarines from China. Myanmar has, over the years, received a huge amount of military equipment, though outdated, from China. The Sri Lankan armed forces operate a variety of Chinese aircraft, patrol boats, tanks and infantry vehicles. Bangladesh has acquired two submarines from China. The Chinese military has now established relations which can be leveraged for strategic advantage, both in times of peace and war. Given below is a representative map of Chinese arms sales in the region.

Gwadar and China

The development of Gwadar till date, after Pakistan bought it from Oman in 1958, has been an ongoing proposition for Pakistan. At various times, the Pakistanis have sought help from a number of countries including the USA, Oman and now China for its development. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is said to have sought US help for construction of a new port at Gwadar, and even reportedly offered the US Navy use of the facility13.

Development of Gwadar. The present development of the port was initiated in 2002 with the Chinese providing 80 per cent of the port’s $ 248 million initial development costs14. It was intended to be a gateway for a supposed trade corridor for the Central Asian Region, China and the Middle East. Consequent to the development of the port, the contract for operation of the port was awarded to the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA) in 2007 for a 40 year period. However, due to irreconcilable differences between Pakistan and the PSA, largely on account of the inability of the Pakistani Government to allot promised land, the contract was terminated and the China Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC), a state run company, was given the contract for operating the port15.

The Chinese Takeover. Under the new agreement, the COPHC will be responsible for the operations of the port and share its profits while the port will continue to remain the property of Pakistan16. The agreement covers the entire existing terminal which has been handed over to COPHC for 40 years as also the development and expansion works at container terminal and the multi-purpose terminal17. The COPHC has also been provided with 2282 acres of land on a 43 years lease, something which had been denied to the PSA.

Gwadar and the CPEC. The Chinese takeover has provided impetus to the idea of a trade corridor between China and Pakistan and consequently led to the formal establishment of an intergovernmental framework for the realization of a CPEC between the two countries during the visit of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to Beijing in July 201318. This visit also resulted in the plan for development of a road and rail link from Kashgar in China to Gwadar which, in theory, would aid in the transportation of oil from the Middle East, offloaded at Gwadar, to China through Balochistan and over the rugged Karakoram mountains. This link would then greatly reduce the current distance of more than 12000 km that this oil takes to reach Chinese ports. While the practicality of such a rail-cum-road link across the Himalayas is questionable for both its feasibility and economic viability in the long term, it has brought the focus of development on Gwadar. Under the CPEC, Gwadar will be the recipient of some Early Harvest Projects (EHP) in the next 3 – 5 years which include an LNG terminal, a free zone and an expressway in addition to port related infrastructure.

China’s Interests. The Chinese have been attracted to Gwadar primarily because of its proximity to the Straits of Hormuz, through which most of their energy flows. Gwadar provides a base from where they can exercise firm control over this energy flow, both in terms of monitoring and protection when the situation demands such effort. With the establishment of a Chinese military base at Djibouti and the continuing anti-piracy effort, naval operations based out of Gwadar will provide the Chinese with a near-continuous naval presence from the Makran coast till the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. Chinese strategists have also been claiming that Gwadar will provide a port for both exporting of Chinese goods and offloading of Chinese energy imports, which will then be transported overland through Pakistan on to China. In fact, Gwadar is also viewed by some of these experts as mitigating the ‘Malacca Dilemma’ faced by the Chinese. The economic viability of transporting energy imports overland from the Makran coast, through the extremely hostile terrain of the Himalayas to China, is extremely doubtful, which is further compounded by the current security problems of Pakistan19. However, the prospect of exporting ready made goods from China’s southern regions through Gwadar, as undertaken by the recent shipment20, seems more plausible. As part of the CPEC, China has also invested in building roads through Pakistan connecting Southern China to Gwadar and Karachi. The existing Karakoram Highway has been widened as part of this project. Consequently, road movement from China has been greatly eased up which facilitates not only commercial movement but also military, if and when the need arises. The economic utility of development of Gwadar port as the gateway for the CPEC is also questionable considering the availability of operational commercial ports at Karachi and Ormara. The Chinese therefore appear to be securing their strategic objectives while riding along with Pakistan as it seeks to fulfil its national aspirations and developmental goals.

Current Status of Gwadar

Port Development. The Gwadar port currently has three multi-purpose berths for vessels with a dredged depth of 14.5 m alongside and in the approach channel21. This permits vessels with a maximum draft of 12.5 m and displacement of up to 70000 t DWT to berth at the port. The COHPC which operates the port, has received possession of about 923 hectares of land for development of a Free Zone and is also contracted for development of port related infrastructure. A Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal, to cater to Pakistan’s domestic needs of LNG and natural gas which are likely to be imported from Iran, is also expected to be constructed as part of the CPEC22. Wu Minghua, a Shanghai-based independent shipping industry analyst, says that "Gwadar will not become China's main trade hub with Persian Gulf countries, not to mention serve as an alternative route to the Malacca Straits"23. Gwadar currently has a handling capacity of just 1 million tonnes and hence will not be able to handle China’s current oil import demand of more than 335 million tonnes. Pakistan has announced ambitious plans of building 100 berths by 2045 for Gwadar in its usual jingoistic vein24. However, the likelihood of fructification of such grandiose plans is quite doubtful, if the progress made in Gwadar over the past decade is anything to go by. Containerized shipments form Gwadar commenced in May 2015 and received a boost in December 2016 with the first cargo from China carried overland through the CPEC being shipped from the port. Current traffic at Gwadar port is largely limited to CPEC related shipments with not more than one ship calling at the port in a week.

Impediments to Development. Gwadar lies in the restive Balochistan province in the West of Pakistan which has been wracked by an insurgency for some time now. The security situation is quite tense with the Chinese consulate in Karachi recently issuing an advisory to Chinese companies doing business in Pakistan to pay closer attention to security, following an attack that appears to be targeting Chinese companies in Balochistan25. This advisory has been issued despite the presence of a 15000 strong force created by Pakistan to guard projects related to the CPEC. The area also suffers from a debilitating shortage of water with crises occurring at regular intervals26.Currently only one major shipping company, COSCO Shipping, currently serves the port, which also almost exclusively carries material for the CPEC27. The likelihood of other shipping companies, especially international entities, operating from Gwadar in the near future is also unlikely in light of the prevailing security situation and the absence of any economic prospects in this region as also the rest of Pakistan. Shortage of electricity is another concern which was highlighted in a briefing to the Pakistani Senate’s Standing Committee on Planning, Development and Reforms in August 2016 by the Quetta Electric Supply Company28.Construction of a desalination plant and power plants to tide over these shortage have been planned but progress has been slow which will have consequential effects on the development of the port. Security in the area will remain a cause of concern since it is rooted in political problems and the Pakistani government has not shown the wherewithal to solve such issues in the past.

The Pakistan Navy and Gwadar. The PN has been charged with the seaward security of Gwadar and had in fact, escorted the two ships which had carried the containers brought in by the convoys over the CPEC in December 2016. The PN has subsequently raised a task Force – TF 88 – for the seaward security of Gwadar comprising ships, fast attack craft, aircraft, drones and surveillance assets. Additionally, marines would also be deployed at sea and around Gwadar for security operations29. The PN has also raised a Coastal Security and Harbour Defence Force for tackling threats along the coast and stationed a Force Protection Battalion at Gwadar for protection of Chinese workers. The PN has a base at Ormara, the Jinnah Naval Base (JNB), which is located about 150 nm (230 km) to the east of Gwadar along the Makran coast. The base is intended to serve as a substitute for Karachi and can berth ships and submarines, including the latest PNF 22 class frigates and the soon-to-be-acquired submarines from China. The PN is also reported to have a small base at Jiwani which is further to the west of Gwadar, close to the Iranian border. The PN air base at Turbat, PNS Siddiq, was commissioned in September 2014, to strengthen seaward security along Makran coast and beyond30. Moreover, the PN has been reported to have been operating from Gwadar in the past after the development of the port in 2005. The PN is therefore, unlikely to develop a naval base at Gwadar though it will continue providing protection to the area as part of its operational responsibilities. However, the larger issue is the rationale of the threat to Gwadar and the CPEC being touted by Pakistan. While the threat ashore in Balochistan on account of the insurgency is understood, the threat at sea is practically absent, especially after the Ship-owners’ Club revised the Northern limits of the High Risk Area in the Gulf of Oman to 22º N, effectively declaring the Makran coast piracy free31.In fact, no attacks were recorded off the Makran Coast or even in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia according to the 2015 annual report on piracy put out by the International Maritime Bureau32.There have also been no reports of any maritime manifestation of the Baloch insurgency in the waters adjacent to the Makran coast. While a country is entitled to take what measures it deems best for threats to its interests, a hyperactive approach, especially if it involves extra-regional states, is bound to raise eyebrows in the neighbourhood and will obviously not add to the stability in the region.

The Chinese Navy (PLAN) at Gwadar. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has operated regularly with the PN for a long time now and has been a participant in a number of bilateral as also multilateral exercises conducted by the PN. Ships from PLAN’s anti-piracy escort force regularly call at Karachi on their way to deployments in the Gulf of Aden and while returning to their home ports. The PN inventory has a large number of Chinese origin ships and platforms including the latest F 22 class frigates. The PN has also signed a recent contract for supply of eight submarines from China by about 2023. A recent Pak-China joint naval exercise held in November 2016, was aimed at promoting maritime security and stability in the region, and specifically focused on challenges to CPEC in security domain33. Some recent news reports have quoted unnamed sources from the PN as saying that China may provide naval assets to guard Gwadar34. However, this has neither been confirmed nor denied by China with the Chinese military spokesperson deflecting the question in a press conference35. Such ambiguous Chinese statements do not in any way indicate Chinese intent as has been observed in the past during Chinese denials of the military base at Djibouti. Reports have also surfaced of the deployment of Chinese submarines at Gwadar adding to the focus on Gwadar by the Indian Navy36. While the veracity of these reports about the deployment of the PLAN may be suspect, the possibility of joint operations of the PLAN with the PN for ensuring seaward security in this area cannot be ruled out. The current ability of Gwadar to support sustained operations of naval ships is definitely limited, especially when considering the proximity of the naval base at Ormara. In fact, the ability of Gwadar to berth commercial ships itself is problematic considering the limited berthing facilities, especially when it has just two tugs. Port visits by PN and PLAN ships may be a continuing occurrence but basing may not be operationally advantageous since there is a full-fledged naval base at Ormara, just about 10 hours away. However, such rationale may not be relevant in the context of the China-Pakistan nexus where strategic considerations may override economic imperatives, especially in the longer term. Notwithstanding the port of operations that may be chosen by the PLAN in Pakistan, the likelihood of involvement of the PLAN in ensuring the security of Gwadar, under the guise of "open seas protection" as mandated in the White Paper on China’s Military Strategy, is very high. The shipping of goods under the CPEC provides the required cover for legitimizing the continued operation of the PLAN in the IOR, despite the absence of any credible threat. These operations of the PLAN will also allow it an enhanced military monitoring capability in this region, which has a multitude of military and naval forces, both regional and extra-regional. It also allows the PLAN to conduct joint operations with the PN and develop capabilities for exploitation in wartime.

Implications for the Region

The viability of the CPEC and consequentially, the economic practicality of Gwadar port, is suspect, at least in the near future, since political stability in Balochistan, so crucial to the success of any such venture, is a mirage on the distant political horizon of Pakistan. However, the Chinese are nobody’s fools to invest $ 46 billion in projects related to the CPEC and neither are they so altruistic as to be involved in the development of a whole region of Pakistan unless there is substantial benefit to be reaped from this harvest. China, therefore seems to have made a strategic investment in Pakistan which is intended for the not so distant future but may not provide any immediate benefits in the near term. In fact, Chinese commentators are rather skeptical of the benefits to China and think that Pakistan stands to benefit more if the projects were to fructify in accordance with the ambitious plans37. Some Pakistani news reports also say that approval has been accorded to the Russians to utilize Gwadar port for their exports as Moscow has apparently shown willingness to be part of the CPEC38. Consequently, Pakistan stands to gain from the development of Gwadar, immaterial of the traffic that the port may or may not generate. The Gwadar Port Authority itself has cited the low number of ship calls as one of the issues hampering the progress of Gwadar port in its report to the Pakistan Parliamentary Committee on CPEC in November 2015.

The worrisome aspect of the development of Gwadar is obviously not about the prospects for commercial shipping but the prospects of operation of the PLAN in this part of the world. The PLAN has been regularly operating in the Gulf of Aden since 2008 with a force of about three ships being on deployment at any given instant. PLAN vessels also undertake regular exercises with the PN as also other nations in the IOR littoral. The region continues to witness increasing sales of Chinese naval assets with Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh being the most prominent recipients. The propensity of the Chinese to leverage the advantage provided by such ‘soft deals’ and the dependence created thereof does not portend well for the developmental interests of the countries involved.

The PLAN is continuously expanding its footprint and also its ambit of operations, which have been, till recently, restricted to Chinese coastal waters. With the new military doctrine of ‘offshore defence with open seas protection’ PLAN capabilities have reached the blue waters of not only the Western pacific, but are increasingly making inroads into the IOR. China has bestowed upon itself the responsibility “to maintain regional and world peace” which may not always be in consonance with the understanding of the countries of the region itself. The increasing footfalls of the PLAN therefore, have a tendency to destabilise the established order in the neighbourhood, as has been witnessed in the South China Sea. Meanwhile the PLAN continues to increase its operational knowledge of the IOR by regular deployment of submarines and intelligence gathering vessels.

The operations of the PLAN are therefore of serious concern to India. The effect of the development of Gwadar, by itself, may not be a troublesome proposition considering its likely future prospects. The naval developments in the PN and the PLAN present a challenge in the operational domain for the Indian Navy (IN) since the earlier envisaged collusion of these two entities is now a reality which will be further strengthened under the garb of Gwadar and CPEC. However, the ability of the PLAN to provide an operational advantage to the PN in the event of a conflict will be limited considering its current inventory and out of area capabilities. India is no Iraq that can be brought to its knees by extra-regional naval might, especially in its own backyard. It is important to note that the PLAN currently has just one aircraft carrier and is still in the process of integrating carrier based air operations into its operational doctrine. Expeditionary operations, of the nature witnessed in the recent past, are therefore sometime away though that should not be a measure of comfort for potential adversaries.

The utility of development of Gwadar as a military base is also questionable in the near term, considering its proximity to India and the prevailing security situation in Balochistan. Operations from the Makran coast, from Gwadar or Ormara, will however provide the PLAN with a viable and effective out-of-area presence, especially after the operationalization of the military base at Djibouti. This will ensure a continuous PLAN presence all the way from the Horn of Africa till the Indian coast giving it an enviable operational advantage in the Northern IOR. Adding to this presence is the possibility of other Chinese developed ports in the region like Hambantota being utilised by the PLAN. The Indian Navy therefore has its task cut out in contending with this factor which has the ability to disrupt its line of operations in the event of a conflict though it may not manifest in a threat by itself in the near term.

Endnotes

- 'Today Marks Dawn Of New Era: CPEC Dreams Come True As Gwadar Port Goes Operational”. The Dawn 13 Nov 16.http://www.dawn.com/news/1296098. Accessed on 21 Dec 18.

- ‘Pak Navy Assembled TF-88 for Security of Gwadar Port’, 12 December, 2016. http://paktribune.com/news/Pak-Navy-assembled-TF-88-for-security-of-Gwad.... Accessed on 19 Dec 16

- ‘Chinese Naval Ships To Be Deployed At Gwadar: Pak. Official’, PTI Karachi, November 26, 2016. http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/Chinese-naval-ships-to-be-dep.... Accessed on 29 Nov 16.

- Defense Ministry's regular press conference on November 30, 2016. Source China Military Editor Yao Jianing Time 2016-12-01. http://english.chinamil.com.cn/view/2016-12/01/content_7385643.htm. Accessed on 21 Dec 16

- Annual Report To Congress - Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015.

- ‘China's 21 Century Maritime Silk Road: Old String with New Pearls?’, Gopal Suri, Vivekananda International foundation. http://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/china-s-21st-century-maritim.... Accessed on 21 Dec 16.

- ‘Chinese Navy Finishes 1,000 Escort Missions At Gulf Of Aden’, Source CRI Editor Zhang Tao Time 2016-12-23. http://english.chinamil.com.cn/view/2016-12/23/content_7421185.htm. Accessed on 26 Dec 16.

- ICC International Maritime Bureau Piracy and Armed robbery against Ships: Report for the Period 1 January – 31 December 2015.

- The Rise in Chinese Overseas Investment and What It Means for American Businesses, Daniel H. Rosen and Thilo Hanemann, http://www.chinabusinessreview.com/the-rise-in-chinese-overseas-investme..., Accessed on 20 Jan 16.China’s Overseas Investments, Lihuan Zhou and Denise Leung, January 28, 2015, http://www.wri.org/blog/2015/01/china%E2%80%99s-overseas-investments-exp..., Accessed on 08 Jan 16.

- Ibid.

- ‘Silk Road Economic Belt: A Dynamic New Concept for Geopolitics in Central Asia’, Pan Zhiping, Director, Central Asia Research Institute at Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, China, http://www.ciis.org.cn/english/2014-09/18/content_7243440.htm, Accessed on 21 Sep 15.

- Quoted in “Examining the Sino-Indian Maritime Competition: Part 3 – China Goes to Sea”, Lindsay Hughes. Strategic Analysis paper 22 Jan 2014.

http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publications/indian-ocean/1507-examin.... Accessed on 15 Sep 15. - ‘A Tale of Two Ports’, Christophe Jaffrelot. Yale Global, 7 January 2011. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/tale-two-ports. Accessed on 28 Dec 16.

- ‘Gwadar Port inaugurated: Plan for second port in Balochistan at Sonmiani’, Saleem Shahid. The Dawn, 21 Mar 2007.

- ‘China Given Contract to Operate Gwadar Port’, Syed Irfan Raza. The Dawn, 18 Feb 2013.

- ‘China Takes Over Gwadar Port’, By Xu Tianran Source: Global Times Published: 2013-2-19 0:23:01. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/762444.shtml. Accessed on 22 Dec 16.

- ‘Gwadar Port & CPEC -A Presentation to Parliamentary Committee on CPEC’, 28 Nov 2015. Ministry of Ports & Shipping, Gwadar Port Authority.http://www.na.gov.pk/cpec/sites/default/files/presentations/Parliamentary%20Committee%20on%20CPECNew.pdf. Accessed on 22 Dec 16.

- Joint Statement on a Common Vision for Deepening Pakistan-China Strategic Cooperative Partnership in the New Era, 05 Jul 2013, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Pakistan.

http://mofa.gov.pk/pr-details.php?mm=MTMwMQ. Accessed on 21 Dec 16. - Read ‘Corridor Calculus CPEC & China’s Comprador Investment Model in Pakistan’, Sushant Sareen, Vivekananda International Foundation, New Delhi, 2016.

- 'Today Marks Dawn Of New Era': CPEC Dreams Come True As Gwadar Port Goes Operational’. The Dawn,13 Nov 2016. http://www.dawn.com/news/1296098. Accessed on 21 Dec 16.

- Nautical information, Gwadar International Terminals Limited. http://cophcgwadar.com.192-185-11-8.secure19.win.hostgator.com/gitl.aspx. Accessed on 26 Dec 16.

- ‘Pakistan to Build LNG Terminal, Gas Pipeline Saturday’,The Financial Tribune,04 Oct 2014. https://financialtribune.com/articles/energy/1894/pakistan-to-build-lng-.... Accessed on 20 Dec 16.

‘Gwadar Port &CPEC - A Presentation to Parliamentary Committee on CPEC’, 28 Nov 2015. Ministry of Ports & Shipping, Gwadar Port Authority.http://www.na.gov.pk/cpec/sites/default/files/presentations/Parliamentary%20Committee%20on%20CPECNew.pdf. Accessed on 22 Dec 16. - Gwadar Port Benefits to China Limited’, Li Xuanmin. Global Times, 23 Nov 16. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1019840.shtml. Accessed on 22 Dec 16.

- ‘Gwadar Port to have 100 berths by 2045: Minister’, Qadeer Tanoli, The News, June 27, 2015. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/48058-gwadar-port-to-have-100-berths-by.... Accessed on 26 Dec 16.

- ‘Chinese Consul Issues Warning to Companies’. Global Times, 06 Dec 16.http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1022228.shtml. Accessed on 22 Dec 16.

- ‘Gwadar May Face Severe Water Shortage’, Saleem Shahid, Dec 10, 2016, The Dawn. http://www.dawn.com/news/1301596. Accessed 15 Dec 16.

- Gwadar, Pakistan Port Growth Lags As Challenges Mount’, Turloch Mooney, Senior Editor, Global Ports, and Peter Shaw-Smith, Special Correspondent, Dec 13, 2016.

http://www.joc.com/international-trade-news/infrastructure-news/asia-inf.... Accessed on 03 Jan 17. - ‘Remedial Measures: Gwadar Facing 22% Power Shortage, Panel Told’, Maryam Usman. The Express Tribune, August 20, 2016. http://tribune.com.pk/story/1166272/remedial-measures-gwadar-facing-22-p.... Accessed on 16 Dec 16.

- ‘Pak Navy Assembled TF-88 for Security Of Gwadar Port’, 12 December, 2016.

http://paktribune.com/news/Pak-Navy-assembled-TF-88-for-security-of-Gwad.... Accessed on 19 Dec 16 - ‘New Naval Air Station’, Sep 4, 2014. http://defence.pk/threads/new-naval-air-station.332196/. Accessed on 12 Sep 15.

- Revision of piracy High Risk Area in the Indian Ocean, 14 October, 2015. The Ship-owners’ Club. https://www.shipownersclub.com/lossprevention/revision-of-piracy-high-ri.... Accessed on 20 Oct 15.

- ICC International Maritime Bureau Piracy and Armed robbery against Ships: Report for the Period 1 January – 31 December 2015.

- ‘Pak Navy Assembled TF-88 for Security Of Gwadar Port’, 12 December, 2016. http://paktribune.com/news/Pak-Navy-assembled-TF-88-for-security-of-Gwad.... Accessed on 19 Dec 16.

- ‘Chinese Naval Ships To Be Deployed At Gwadar: Pak. Official’, PTI Karachi, 26 November 2016. http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/Chinese-naval-ships-to-be-dep.... Accessed on 29 Nov 16.

- Defense Ministry's Regular Press Conference on November 30. China Military Editor Yao Jianing, 01 Dec 16. http://english.chinamil.com.cn/view/2016-12/01/content_7385643.htm. Accessed on 02 Dec 16.

- ‘Aware Of Chinese Submarine Deployment At Balochistan's Gwadar Port: Navy Chief’, New Delhi, 02 December 2016. http://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/aware-of-chinese-submarine-deplo.... Accessed on 04 Dec 16

- ‘Gwadar Port Benefits To China Limited’, Li Xuanmin. Global Times, 23 Nov 16.http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1019840.shtml. Accessed on 30Nov 16

- ‘Russia allowed use of Gwadar Port’ Khalid Mustafa & Muhammad Saleh Zaafir. The News, 26 Nov2016. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/167827-Russia-allowed-use-of-Gwadar-Port. Accessed on 07 Dec 16.

Published Date: 18th January 2017, Image Source: https://encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com

Post new comment