One of the good fallouts of the Union Government’s demonetisation drive has been a renewed demand for reforms in the funding of political parties. After all, since demonetisation is supposed to tackle black money and the role of black money in politics is an open secret, it is only natural for a proactive Government to turn its attention sooner than later to the menace that looms right in its backyard. There are two ways to handle the issue. The first is to adopt state funding of parties, partially or fully, where parties and elections get money through the public exchequer as part of what can be called “election funds’. This subject was discussed at length by this author in the In Perspective column under the title, ‘State Funding of Elections and Political Parties: Is India Ready’ (November 22, 2016). Because the money would come from the Government, it would be fully accounted for and there would be strict monitoring of the ways the amount is spent; there would also be guidelines to determine the eligibility for securing such funds. State funding remains a subject of discussion and will remain so for a while, because an early across-the-board political consensus will not easily come. The second way to reform political funding is to bring complete transparency in the private funds that parties receive at present and enhance accountability through technological means.

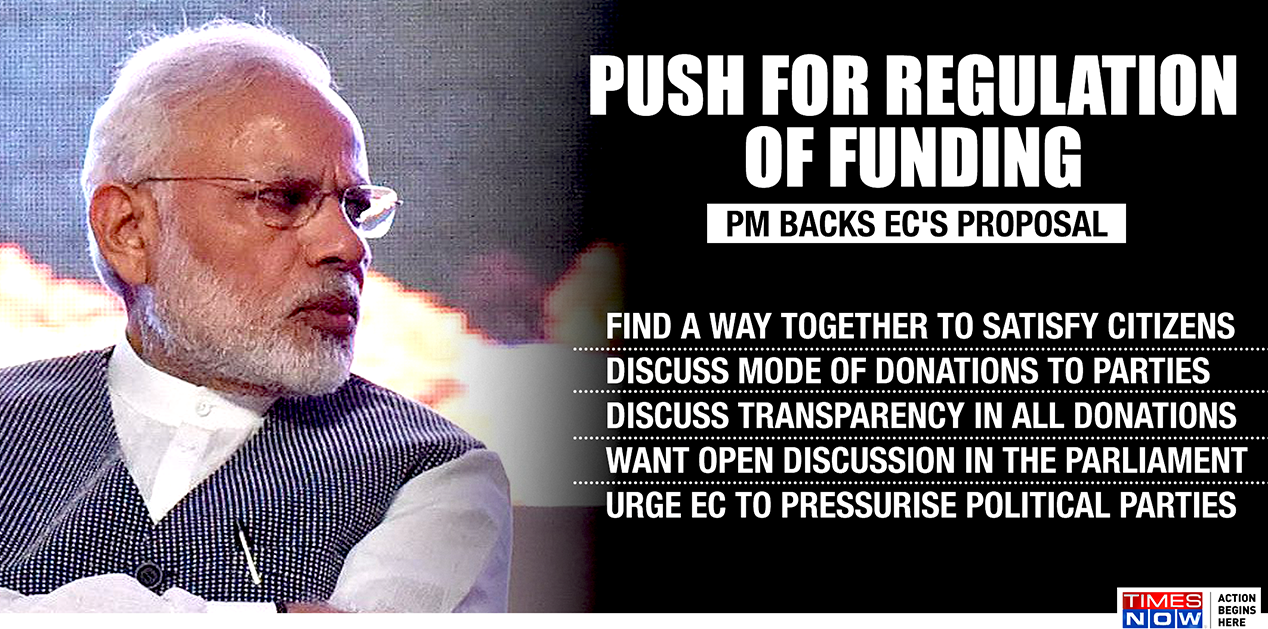

Prime Minister Narendra Modi understands that his demonetisation drive will gain further credibility if he takes steps to clean up the political system. He had earlier called upon parties to seriously discuss the idea of state funding, and has now pitched strongly for transparency in private money receipts. A week after the demonetisation decision and on the eve of the winter Session of Parliament, the Prime Minister had floated the suggestion at an all-party meeting that it was time for everyone to put their heads together and discuss electoral reforms vis-à-vis funding of parties and polls. This January 7, he told a party gathering at the National Executive that “people have a right to know where our funds are coming from”.

The Prime Minister’s remark are timely and also interesting in the choice of words. He has put the onus on his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to lead by example, through the use of the phrase, “…where our funds are coming from”. It implies that Prime Minister Modi is not averse to the idea that even donations of upto Rs 20,000, which can be made in cash and the donor’s name need not be disclosed as per existing law, should be opened up. In other words, the party should have no qualms in making public the donor’s name public. This is a significant indicator because until now, political parties have quoted the law to refrain from being transparent about such donations. If indeed the BJP takes the initiative on a voluntary basis, it will serve the interests of transparency, give the party a moral high ground to perch on, and pressure other parties to follow suit.

The Prime Minister then went on to extend the appeal to the political class in general. He said, “A culture of transparency is emerging in the country and politicians should use their wisdom to bring in transparency.” It will be difficult for any political party — even his bitterest rivals — to fault his observation or contest it. In fact, there are certain opposition parties which are in consonance with his stand and have been pushing for such reforms in the political system. A few of these leaders have been openly voicing their support. Senior Janata Dal (United) leader Pawan K Verma, writing in the Times of India of January 7, said “it is time that our politicians stop pointing the finger at others and look at the cesspool in their own backyards”. Prime Minister Modi’s call has been no different, except that he has been pointing fingers at others and also towards the political system he belongs to. Interestingly, Verma’s leader and Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has been a vocal supporter of the demonetisation decision from the day the Prime Minister announced it. This has resulted in a great deal of annoyance among his allies, the Rashtriya Janata Dal and the Congress, but he has remained steadfast in his endorsement.

It’s generally the case that the bulk of donations to a political party comes from unnamed sources who put in less than Rs 20,000 in the party’s kitty. This loophole in the law is exploited to defeat the very purpose of transparency. The Election Commission of India (ECI) has recommended that the Government bring in changes to the law to ensure that individual anonymous donations are less than Rs 2,000. There are two aspects here. The first is that political parties are suspected to have used the provision to accept large sums of donations from an individual source and then split the amount to less than Rs 20,000, showing them against a bunch of donors (real or manufactured). Since the identities are not required to be revealed, there is no fear of being caught in the act. The second point is that, even when the donors are genuine, the cumulative donations are huge and yet they escape scrutiny. According to statistics put out by the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR), an organisation engaged in the task of prompting greater accountability and transparency in the public system, more than 80 per cent of the total income of political parties comes from unnamed sources. While the income from these unnamed sources is declared by the parties in their income tax returns, the sources remain hidden — thereby raising a question mark on the legality of the funds received. The opaque income is not limited to contributions from donors but also includes relief fund, sale of coupons for raising money etc.

In its 2015 report, ADR said that in 2013-14, just 41 per cent of the total donations the national parties received came from voluntary contributions amounting to more than Rs 20,000. Besides, the report also pointed out that nearly 60 per cent of the total donations to national parties during the fiscal 2013-14 were collected from donors whose details were unavailable in the public domain. To better appreciate how political parties have over the years used the law to escape accountability and keep their funding shrouded, it would be useful to recall how they tried to even escape from paying income tax on the pretext that they were not involved in commercial activity. Section 13A was introduced to the Income Tax Act, 1961, which exempted political parties from paying income tax. All that the parties had to do was to file their tax returns, failing which the exemption would be withdrawn. This provision was inserted by the Taxation Laws (Amendment) Act, 1978, and became effective in April 1979. The parties had to maintain proper books of account and details of donors who contributed in excess of Rs 20,000, and get their accounts audited. But even this relaxation was not enough for parties to follow the law, as many of them failed to file returns and yet continued to enjoy exemptions. This of course raises a question mark on the integrity of the Income Tax Department which did precious little to counter the illegality, but that’s a different matter. Finally, in 1996, the Supreme Court stepped in after a non-governmental organisation filed a public interest litigation in the matter. The court clearly stated that political parties which failed to file their tax returns would lose the exemption; in other words, they would have to pay taxes.

Parties were then compelled to fall in line. But they continued with their opaque ways. In 2006, after the Right to Information Act (RTI Act) came into force, the ADR sought details of the income tax returns of various political parties from the department. But the tax authorities refused to oblige on the ground that the information sought did not fall under the RTI purview. The ADR took the matter to the Central Information Commission (CIC), which ruled that political parties could not claim special privileges on the issue. In its April 2008 order, the CIC went a step further and said that six national parties be designated as public authorities and that they must respond to queries under the RTI. This rattled everyone and the Manmohan Singh Government reportedly considered bringing an Ordinance to nullify the CIC order. But then it was ousted from power. The matter meanwhile went to the Supreme Court, where it now rests. Prime Minister Modi’s remarks have aroused fresh hopes that old mindsets will finally change.

The political class should be worried by the findings of the international non-profit organisation, Global Integrity. In its report of 2011, it gave a zero score to India out of 100 in the implementation of and disclosure of political party and candidate funding information to the public. The country also got a duck on the effectiveness of its party funding regulations. The fact that the report gave it a decent 67 out of 100 on the regulations in place, shows that while laws are in place, they are adhered to by parties only in the breach. On the matter of individual candidate financing, India got a dismal 28 marks. Things haven’t improved much over the five years since that report, and they will not unless the political class embraces the Prime Minister’s call and assists the Government in bringing about the changes that are desirable and implementable. The Winter Session of Parliament had been a good opportunity to initiate a serious debate on the issue, which is what Prime Minister Modi had appealed for. Unfortunately, leading opposition parties had other plans; they disrupted Parliament’s functioning and allowed virtually no business to be transacted. Neither demonetisation nor the issue of electoral reforms got a chance to be discussed. Ironically, the Trinamool Congress, which had, at the all-party meet, endorsed the Prime Minister’s suggestion to discuss electoral reforms, was among those who spread mayhem in the two Houses of Parliament, using demonetisation as an excuse.

Besides suggesting a cap of Rs 2,000 for anonymous donations, the Election Commission of India has asked the contesting candidates to open separate bank accounts for cheque payments. All poll-related expenses have to be incurred from that bank account. Also, candidates will have show vehicle hiring charges and fuel expenses from this election expenditure account. Although welcome and in keeping with the need to more effectively monitor election expenses of candidates who tend to fudge accounts, the ECI’s directive is not new. Back in 2013, the Election Commission in Chandigarh had asked candidates to do the same; while last year, a district election officer in Guwahati had requested candidates to open separate bank accounts for election-related expenses. He said the account could be opened at least a day before the candidate intends to file the nomination, and that the account could be in the candidate’s name or jointly in the name of the candidate and his/her election agent. The difference this time around, though, would be a greater scrutiny by the ECI of movement of large amounts of cash; and the general non-availability of huge piles of cash in the wake of demonetisation and the withdrawal of old high-denomination currencies that were awash in the Indian black economy. A great deal of rumbling that we have been hearing from certain opposition parties against demonetisation has to do with the fact that suddenly, their access to unaccounted money has been cut off, or severely limited — and that too in an election season.

Given the Government’s push to less-cash and more digital transactions, there is no reason why the concept cannot be promoted in the area of smaller donors to political parties. Since the Prime Minister has exhorted his supporters and his party to show an inclination for change, perhaps the BJP could begin by encouraging its contributors who donate less than Rs 20,000, to do so through the digital mode or by cheque. Of course, it’s an idea that should be adopted by other political parties as well, but this will happen if the parties agree that such small donors need not remain anonymous and that complete transparency is the demand of the day.

In line with greater transparency in funding is the issue of auditing. As of now, political parties are required to get a certificate from the Election Commission that they have submitted their audited accounts for the year. But the audit itself is a matter contention. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI) had in its report of 2012, noted that “the present system of accounting and financial reporting followed by political parties in India does not adequately meet the accountability concerns of the stakeholders”. The ICAI, as desired by the Election Commission of India, then went on to make a host of recommendations which were submitted in the form of a report. Unfortunately, very little has been made in the direction of implementing those suggestions. Interestingly, while candidates are required to declare their assets and liabilities, political parties don't have to follow this rule. The tax return statement they file is before the Income Tax Department which, as we have see earlier, has refused to share it in the public domain.

Among the changes that parties could consider is the opening up of account books of political parties to the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) empanelled auditors. This is a sensitive issue and not many parties would be willing to go this far. In the course of a hearing of a public interest petition filed by a journalist in the High Court in Hyderabad in March 2015, this very appeal had been made. The petitioner had argued that audits by CAG-approved auditors would be more stringent, reliable and trustworthy. In fact, as the amicus curiae in the Hyderabad court said, the Law Commission of India had submitted a report to the Union Ministry of Law and Justice, suggesting precisely this. In an article for Business Line, commentator Mohan R Lavi wrote in February 3, 2011: “A nation way below in brand image, Tanzania, amended its Political Parties Act, 1992, empowering its CAG to audit the accounts of political parties prior to an election. The parties were forced to divulge all sources of funding irrespective of the source of funds and the status of the funder.” The author did admit that the audit process was not a “runaway success”, but it still did provide “some good indicators to improve accounting and disclosure practices in political parties”. Perhaps India could take a leaf out of Tanzania’s experiment.

All in all, the need for deep reforms in the funding of political parties cannot and should not be delayed. The demonetisation process has initiated a fresh bout of interest in the subject and the momentum must not be lost. There are media reports that the Modi Government could bring a Bill in this respect in the coming Budget Session of Parliament. That would be welcome.

The writer is Opinion Editor of The Pioneer, senior political commentator and public affairs analyst.

Published Date: 10th January 2017, Image Source: http://www.timesnow.tv

Post new comment