Introduction

Uzbekistan and China recently celebrated 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations. In recent years, the two countries have developed robust bilateral ties marked by high degree of economic engagements. China has been Uzbekistan’s second largest trading partner and the biggest source of investment for three years in a row. Uzbekistan sees this investment as essential for its development. On the other hand, China considers Uzbekistan a key partner in development of One Belt One Road (OBOR), and therefore, is investing heavily in infrastructure, transport and communication. Trade and economic relations between China and Uzbekistan are supported by political understanding between the two republics.

Geo-Strategic Significance of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a geo-politically important country. Its significance firstly comes from the strategic location. It is centrally located in Central Asia, and borders all other Central Asian Republics (CARs) and Afghanistan. It is the only doubly landlocked country in Asiai. However, Uzbekistan is trying to convert its landlocked status from disadvantage into an asset, by constructing trans-national rail and road connectivity with other regional powers. The country can potentially act as a transit link in regional, trans-regional and trans-continental networks. This makes Uzbekistan important for development of OBOR or the International North South Transit Corridor (INSTC) envisaged by India, Iran and Russia.

Secondly, Uzbekistan is the second largest economy of the regionii. It is the most populous country in Central Asia, with around 32 million populationiii. Almost half of Central Asian peoples live in Uzbekistan. Therefore, it is the largest market in the region. Uzbekistan has abundant natural resources like oil, natural gas, uranium, copper, silver and gold. Its sizeable gas and uranium reserves can play significant role in enhancing energy security in the region, particularly in energy-hungry countries like India and China.

Thirdly, Uzbekistan, like other countries of the region, has faced threats of terrorism and radicalization. Organizations like Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and HizbulTahrir (HT) emerged from the Fergana Valley region, which is split between Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In the immediate aftermath of independence, these organizations challenged the secular regime of Uzbekistan. The Uzbek regime could successfully put down this threat in 1990’s. However, proximity to the troubled state of Afghanistan makes Uzbekistan vulnerable to spillover effects from across the border.

After independence, Uzbekistan adopted an independent foreign policy based on national interests, and maintained equidistance from all the major powers. Uzbekistan supported the US and NATO forces during the Afghan War, and allowed opening of a US air base in Karshi-Khanabad in 2001. This base was closed down in 2005, as Uzbekistan’s relationship with the west soured after the Andijan incidentiv. Uzbekistan’s Foreign Policy Concept of 2012 announced that no foreign military base shall be allowed on its territory. It also ruled out membership of military alliances, participation in international peacekeeping missions, and playing role of the mediator in international conflictsv. After the pronouncement of this Concept, Uzbekistan withdrew from Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). This move of Uzbekistan gave a blow to its relationship with Russia, which traditionally played the role of a patron of the CARs. Nonetheless, this positively impacted Chinese engagements in Uzbekistan, as China could aggressively put forward its economic agenda, and has not pronounced any military designs in its bilateral ties with Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan-China Bilateral Relations: Political Understanding

The bilateral relations between Uzbekistan and China go back to the Silk Road, which carried out most of China’s ancient trade. Chinese silk, paper, tea and other products once dominated the markets of cities like Samarkand and Bukhara. The age-old economic links were seldom interrupted by political factors. As a matter of fact, China and Uzbekistan were never part of a unified political entity, barring a few years of reign of Chengiz Khan, a Mongolian invader of the 12th century, who had conquered most parts of China, Central Asia and West Asia. Because of vibrant commercial relations and limited political contact, the two civilizations had very few points of conflict in history.

Unlike CARs of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Uzbekistan does not share border with China. After independence, above three republics had to tackle border disputes with China, which was not the case for Uzbekistan. Moreover, these three CARs are home to considerable Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic group which inhabits Xinjiang province of China. The ethno-linguistic and cultural spillovers among Turkic peoples on both sides of the border influence China’s relations with these CARs. Pertaining to absence of border dispute and inter-ethnic tangle, Uzbekistan and China relationship began on a positive note.

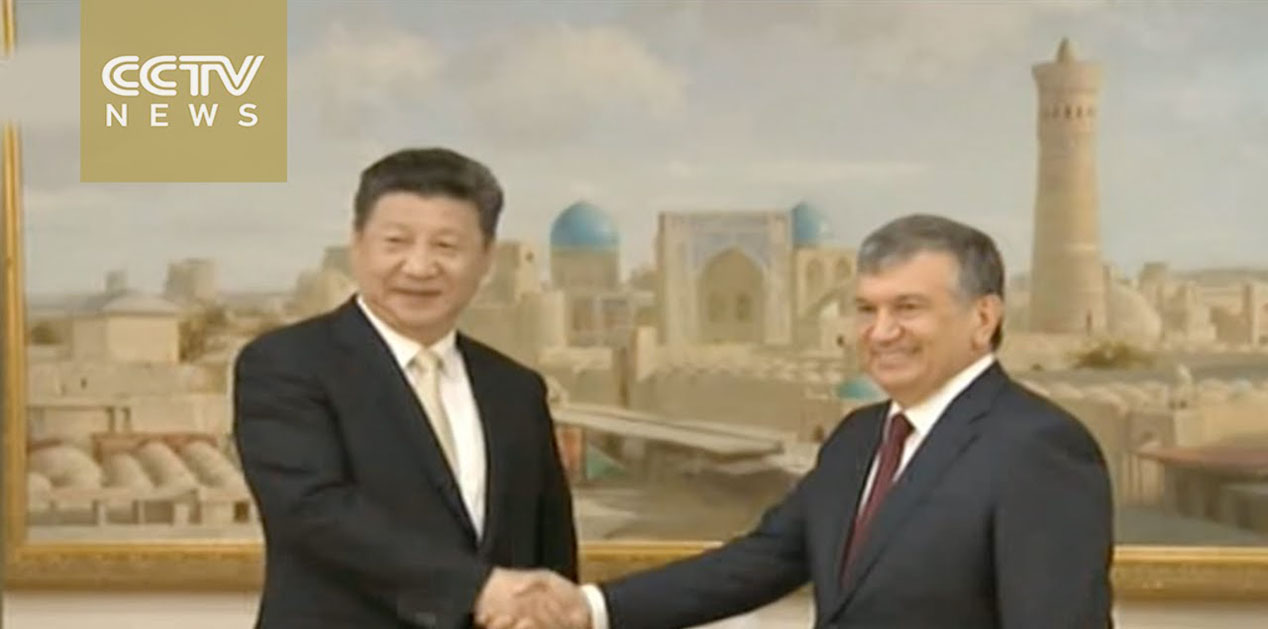

China recognized independence of Uzbekistan on 27 December 1991 and the two republics established diplomatic relations on 2 January 1992. Since then, several high level visits have taken place between the two. Former President of Uzbekistan, late Islam Karimov, paid nine official visits to China during his tenure (1991-2016). Several high-level visits were also carried out by successive Chinese Presidents. After his accession to power, President Xi Jinping visited Uzbekistan twice, in 2013 and in June 2016vi. During Karimov’s trip to Beijing in 2012, ‘Strategic Partnership’ was established between the two countries, and contracts worth USD 5.3 billion were signed. This trip was reciprocated by President Jinping through 2013 visit to Tashkent, when 31 agreements were penned down to implement projects worth USD 15 billionvii.

President Jinping’s June 2016 visit to Uzbekistan was a breakthrough in multiple ways. The tour kicked off from Bukhara, historical city which played significant role in the Silk Road trade. During the visit, Jinping and Karimov inaugurated China-sponsored Kamchiqrailway tunnel that connects Tashkent with the Fergana Valley. Both these gestures were suggestive of China’s interest in development of its Silk Road Economic Belt in cooperation with Uzbekistan. In Tashkent, Jinping participated in the 15th Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). He also held bilateral talks with Karimov, which elevated the relationship to ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’viii. On 22 June 2016, Jinping addressed the Oily Majlis, marking the first address by a foreign leader to the Uzbek Parliament.

The edifice of China-Uzbekistan strategic partnership is built on the pillar of mutual political understanding. The two countries have always supported each other’s security, sovereignty and territorial integrity. While firmly backing each other’s choices of ‘development paths’, they have followed the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs. China stood by the Uzbek regime during the Andijan Incidence (2005), which was criticized by the US and the West in terms of human rights violations. This event led to China and Uzbekistan coming closer to each other.

China and Uzbekistan have enhanced coordination in the regional and international issues. They have pledged cooperation in fighting the ‘three evil forces’ of terrorism, extremism and separatism, and also in fields of cyber security, drug trafficking and cross-border organized crimeix. Security challenges like, radicalization in the Fergana Valley, threats from IMU and HT, increasing number of Central Asian fighters joining the Islamic State are faced by all CARs. China is also worried about these challenges, along with its own challenge of Uighur separatism. Moreover, China and CARs are concerned about the spillover effects from Afghanistan that may disturb the region. Therefore, China and CARs are cooperating in this regard at bilateral and multilateral levels.

Multi-lateral cooperation between China and the CARs is taking place mainly through Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The Shanghai Spirit of mutual cooperation and non-interference brought Russia and China together, along with the four of five CARs in 2001. China considers SCO to be a significant organization in engaging the CARs. SCO members have established coordination in defense cooperation, intelligence sharing and counter-terrorism activities. SCO’s counter-terrorism unit called Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent has proved to be an effective institution against regional terrorism and violent extremism. SCO celebrated its 15th anniversary in Tashkent in 2016, and is now on the verge of first expansion since establishment. Two important countries of the region, India and Pakistan, are going to become the members of the SCO. The proposed expansion of SCO will call for further cooperation from the member countries. However, in the near future, China is likely to continue to exert its supremacy in the SCO.

China’s Economic Engagements in Uzbekistan

As mentioned above, China is focusing more on the economic agenda in its engagements with the CARs, which is beneficial for both sides. Economically engaging with Uzbekistan is vital for China in three aspects, namely, trade, energy and transit. In 1992, ‘Economic and Trade Agreement’ was signed between Uzbekistan and China, whereby they granted Most Favored Nation (MFN) status to each other. In last ten years, bilateral trade between the two increased ten times. In the year 2015, about 20% of Uzbekistan’s imports came from China; and about 17% of its exports went to Chinax.

However, there is an imbalance in the types of goods which are exchanged in this trade. Uzbekistan’s exports to China are mainly dominated by primary goods, but its imports from China are mostly the manufactured good. ‘Made-in-China’ products dominate the Bazaars of Tashkent and other Uzbek cities, which include electronic items, toys, cloths, and fashion accessories. Uzbekistan is a major green-tea drinking nation, and import of Chinese tea is also on rise. On the other hand, tasty fruits produced in the Fergana Valley make their way into China.

2015-16 marked a modest increase in Uzbekistan’s gas exports to Chinaxi; and it is likely to increase further. Uzbekistan’s gas export to China is integrated into larger energy trade network between China and CARs. Central Asia-China gas pipeline starts from Turkmenistan and transits through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan before entering Chinese province of Xinjiang. Uzbekistan also exports large portion of its Uranium to China.

Beijing’s most impressive appeal to Tashkent lies in its ability to offer investment. According to an Uzbek news agency, over 650 enterprises operate in Uzbekistan which have full or partial funding from the Chinese investorsxii. The joint ventures are spread across various fields including energy cooperation, transport, communication, agriculture and education. The investment from China is seen in Uzbekistan as necessary for development.

China and Uzbekistan have been part of the trans-continental trade and connectivity network, which is more than 2000 years old. OBOR, President Jinping’s signature foreign policy project, proposes to revive these ancient networks. Uzbekistan announced its support to the initiative immediately after its announcement in 2013. According to Uzbek experts, the project is beneficial for Uzbekistan for three reasons, viz. national development, regional economic integration, and regional and trans-regional partnerships.

In recent years, China and the CARs have experienced euphoria around the term Silk Road, which is partially triggered by state and media propaganda. In Uzbekistan also, re-glorification of Silk Road is welcomed with great enthusiasm among the people. The State and the people have took part in organizing academic conferences, consortiums, festivals in this arena. Naming of a metro station in Tashkent city as Buyuk-Ipak-Yoli(meaning the Great Silk Road in Uzbek language) is also suggestive of the excitement about the proposed revival.

OBOR envisions two land links form China, one through Mongolia and Russia on to Eastern and Northern Europe; and the other through Central Asia and West Asia on to Western Europe. China is planning to build a High Speed Rail network along the Eurasian region, which includes construction of three rail roads and several transit hubs on aforementioned corridors. Among these three routes, the southern-most route passes through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. In this regard, development of China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway is of vital significance.

China recently sponsored construction of the Kamchiq tunnel, which connects the Fergana Valley region of Uzbekistan to Tashkent. This 19.2 km long tunnel was built by China Railway Tunnel Group at a cost of US $455 millionxiii. It was inaugurated by Chinese President Jinping and the then Uzbek President Islam Karimov on 22 June 2016. The project is part of the 124 km long Angren-Pap railway line that provides cheap and convenient alternative to the old Soviet-era railway line, which had to pass through Tajikistan for connecting the Fergana Valley with rest of Uzbekistan. This tunnel is part of the envisaged China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway line.

In case of the Chinese economic engagements in Uzbekistan, political understanding between two powers plays a significant role. Unlike the US and the European countries, which keep democratization and human rights as a precondition for investments, Chinese investment comes with minimal political conditioning. The Chinese seldom interfere in the domestic political developments in CARs, which makes Chinese investment a convenient affair for countries like Uzbekistan. In addition, China has so far been supportive of the ruling regimes in CARs and has criticized the US attempt of Colored Revolutions. China believes that regime stability in CARs is precursor to development of the region. Central Asian regimes have also reciprocated this stand of China, and have supported Chinese stance about Uighur separatism.

Apart from economic inroads, Chinese soft power appeal is also on rise among Uzbek people. The first Confucius Institute in Central Asia was opened in Tashkent in 2005; later its branch opened up in Samarkand in 2014xiv. These institutes have robust following among Uzbek urban youthxv. Number of young people learning the Chinese language rising; they are also attracted to the Marshall Art, Tai Chi, Chinese music and dance, etc. Chinese National Cultural Center in Tashkent also has reasonable following; it provides scholarships for Uzbeks looking to study in China. Number of Chinese tourists visiting Uzbekistan has increased in recent years. Thus, China has been successful in enhancing people-to-people contact between the Chinese and the Uzbeks.

Chinese engagements in Uzbekistan also face certain challenges. Firstly, there is dissatisfaction among Uzbeks about the projects funded by China, as they bring in workers from China and taking away the Uzbek jobs. The Uzbek government has not produced any authentic data on the number of Chinese workers in Uzbekistan. But estimates suggest that the number is very high. Secondly, increasing export of natural gas to China has caused discontent among Uzbek citizens, as it causes scarcity of gas for domestic use especially during winters. Such discontent is seldom reported in the media. Lastly, Uzbekistan is also going closer to other East Asian powers like South Korea and Japan. These countries are also investing millions of dollars in Uzbekistan. Korean films and art forms are very popular in Uzbekistan; Koreans also form significant diaspora in Tashkent. This has implications for Uzbekistan’s relations with China. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, China-Uzbekistan relations are expanding in all directions, the reason being political understanding between the ruling regimes.

Conclusion

China has emerged as a significant regional power in the 21st century. With high economic growth, military might and political dominance, China has stretched its wings in all directions. Now, OBOR is set to further expand China’s external outreach. The CARs feature prominently in China’s foreign policy goals. China’s trade routes to Europe and West Asia pass through Central Asia. It imports significant amount of oil and gas from CARs through pipelines. China’s special attention to the CARs also comes from common security threats like terrorism and violent extremism.

In recent years, China has aggressively put forward its economic agenda in Uzbekistan, although it has been very cautious about pronouncing any military designs in bilateral engagements. Through conscious political understanding, cooperation with the regime, and support to its ‘development path’, China has smartly tried to pull Uzbekistan in its orbit. Uzbekistan, which conducted independent foreign policy and maintained equidistance from major powers in initial years of independence, seems to have bowed down to Chinese regional hegemony in recent past. China’s increasing trade and investments, coupled with a degree of cultural inroads and soft power appeal, has definitely set alarming bells for other powers in the region.

Endnotes

i. Doubly landlocked country is the one which is surrounded by all the landlocked countries. Uzbekistan is surrounded by 5 landlocked countries, namely, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.

ii. Kazakhstan is the largest economy of Central Asia.

iii. http://ut.uz/en/opinion/uzbekistan-s-population-oversteps-32-million/

iv. An armed uprising occurred in the Uzbek city of Andijan on 13 May 2005. This revolt was against the secular Uzbek regime. The uprising was cracked down by armed security personnel of the Uzbek State. In this incident, number of men and women from both sides were killed. This event was painted in different colors by the state and the western media. The US and the West criticized Uzbekistan for human rights violations in the crack down. However, actions of the Uzbek State were supported by powers like China and Russia.

vi. http://mfa.uz/en/cooperation/countries/374/

vii. Ibid

viii. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1375048.shtml

ix. Ibid

x. Uzbekistan: Country Report, December 2016, Economist Intelligence Unit, UK, pp. 13.

xi. Ibid, pp. 8.

xii. http://kun.uz/en/news/2016/07/02/uzbekistan-china-new-stage-of-cooperation

xiii. http://www.eurasianet.org/node/79381

xiv. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-06/21/c_135455059.htm

xv. http://www.eurasianet.org/node/79381

Published Date: 16th February 2017, Image Source: http://www.youtube.com

Post new comment