One significant outcome of India’s federal structure has been the formation and the rise of regional parties. The federal nature of the state, enshrined in the Constitution and represented in our socio-cultural ethos, allowed space for the projection of regional aspirations through State-specific political parties — it’s a different matter that some of these outfits have, in the course of time, sought to expand their footprints beyond their home ground. From Chennai to Kashmir and from Bhubaneswar to Mumbai, regional parties were born, and they prospered in the years thereafter. They have played important roles in national governance as well.

The list is long: Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, All India Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, Janata Dal (Secular), Shiv Sena, Telugu Desam Party, Biju Janata Dal, Trinamool Congress, Rashtriya Janata Dal, Janata Dal (United), Indian National Lok Dal, Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, National Conference, Peoples Democratic Party, Shiromani Akali Dal, Aam Aadmi Party — and many more. Interestingly, while these have traditionally been opposed to national parties, they have often clashed with one another when it came to hegemony on home turf, often joining hands with national parties to keep their local rivals out. Equally interestingly, these regional outfits have at times, even if rarely, come together to shut the door on national parties. Thus, for a brief moment, the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party were in coalition to deny the Bharatiya Janata Party a chance to rule. Let’s also not forget that the Bahujan Samaj Party and the BJP had come together to edge out the Samajwadi Party, and the Samajwadi Party has today formed an alliance with the Congress for the ongoing Assembly election in UP in a bid to dent the influence of both the BJP and the BahujanSamaj Party. It is this flexibility that has helped the regional formations remain relevant and progressing.

But, if there have been remarkable successes, there have also been a few astounding failures. Perhaps the most significant of them is that of the Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party (MGP) of Goa. Few people today would be able to appreciate that the MGP was the dominant political force in the first two decades after Goa’s liberation from Portuguese rule in 1961. By all expectations, the party was there to stay, and stay in robust health. Its clout can be understood from the fact that it decimated the powerful Congress’s challenge in the first Assembly election held after liberation and formed the first elected Government. The party’s dream run, which began in 1963, lasted right up to the end of 1979. Thereafter began the process of a steady but certain disintegration. Today, the MGP is a pale shadow of its former self. While other major regional parties across the country have gone from strength to strength, the MGP has gone from being weak to weaker.

What has led to the humiliating downgrade of this once robust regional outfit? How is it that the MGP first ceded ground to the Congress and then to the BJP? Why is it that over the decades, many of its prominent leaders abandoned the party and joined the BJP or the Congress? How is it that the once formidable MGP has today been reduced to aligning with a breakaway faction of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) led by Sangh rebel Subhash Velingkar for the Assembly election — voting for which took place in the first phase of the ongoing elections? To understand the causes of the MGP’s current pitiable state, one has to begin from the beginning. The beginning begins with a down to earth, man of the grassroots and no-frills politician: DayanandBandodkar, the party’s founder.

Dayanand Bandodkar is synonymous with the MGP in the same way as Mulayam Singh Yadav is with the Samajwadi Party, Kanshi Ram is with the Bahujan Samaj Party, Biju Patnaik is with the BJD, Lalu Prasad is with the RJD, MG Ramachandran is with the AIADMK, NT Rama Rao is with the Telugu Desam Party, Bal Thackeray is with the Shiv Sena and M Karunanidhi is with the DMK. A wealthy mine-owner, Bandodkar had political ambitions. He founded the MGP as a vehicle to serve the interests of the backward class Hindu population which had borne the brunt of the Portuguese excesses the most. Additionally, he believed that tiny Goa was socially and culturally aligned with neighbouring Maharashtra to such an extent that its merger with the latter was a natural corollary after liberation. His view had followers but detractors too, with the latter believing that a merger with Maharashtra would mean an end to the Goan identity. Nevertheless, in the months following liberation, Bandodkar and his MGP managed to win over the support of backward class Hindus, if not for merger with Maharashtra, then for their socio-economic upliftment. He led MGP to a sweep in the first post-liberation election in 1963. The Congress was shocked; it had thought that the people of Goa would reward it for its role in the liberation movement. The defeat led then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to remark: Ajeebhain Goa ke log” (the people of Goa are strange/unique).

The souring of Bandodkar’s dream of Goa’s merger with Maharashtra notwithstanding (Goa was declared a Union Territory), the MGP continued its forward march. The only other prominent player, the Congress, was seen as a party which represented the interests of the well-off sections of society. It was also considered as being ‘soft’ on Christians, a community which the MGP, at least then, painted as being in cahoots with the Portuguese. It didn’t matter to the MGP that Christian leaders were among the most strident in their condemnation of Portuguese rule and had led the liberation struggle. Offhand, the name that comes to mind is Tristao de Braganza Cunha. Known as the ‘father of Goan nationalism’, he had organised the first movement to end Portuguese rule in Goa (in the mid-1940s, he had invited Ram Manohar Lohia to address a gathering in Goa’s commercial hub, Margao).

But we are digressing. All said and done, the MGP was cruising along pretty well and the Congress was sulkily playing the opposition party’s role. The shrewd and populist politician that he was, Bandodkar brought in legislation to protect the interests of the Mundkars (people who dwelt on the property of others and tilled their land; these others were the Bhatkars). He also commenced upon an overall development plan for Goa. The people gave him unstinted support, and he formed the Government again in 1967 and in 1972; he died in office in 1973. Like Bal (Thackeray) came to be addressed as Balasaheb and J Jayalalithaa as Amma, Bandodkar had become Bhausaheb (elder brother) to Goans.

His death was a major blow but it did not end the MGP experiment. Indeed, his daughter and politician in her own right, Shashikala Kakodkar took over as Chief Minister by popular demand — becoming the first and so far only woman to have been Goa’s Chief Minister. But this was the seventies and times had begun to change. The fixation over merger with Maharashtra was all but buried and the new generation was content with being Goan. She had already tasted bits of politics from her father and also from the fact that she had successfully contested two Assembly elections before taking over the mantle after her father. Indeed, for a year, she served as a Minister in her father’s regime. She ruled from August 1973 to the middle of 1979. By all accounts she was an efficient administrator — certainly more efficient than her populist father — and had a sound grasp over the complexities of governance. But the last year (or what became the last year) of her tenure was heavily dotted by internal rebellion which she could not manage. In fact, the seeds of the MGP’s disintegration were sown during these contentious months of 1979. Her leadership skills were put to test, but she failed, largely because her opponents in the party had already made up their minds to walk away, and also because she could not satisfactorily explain the explosive charges of favouritism she had allegedly indulged in. In hindsight, it can be said that the rebels had calculated well. One of her colleagues and prominent Minister, Pratapsing Raoji Rane, went on to replace her as Chief Minister and rule uninterruptedly for nearly a decade. But this happened only after a spell of President’s Rule.

The defections had hit the MGP hard, but there are instances of regional parties bouncing back after having faced similar challenges. In fact, they have even returned to power after being humiliated in elections. The MGP leadership too could have taken the hit on its chin, rebuilt the party and kept the morale of its cadre high. After all, the Congress regime that was formed, largely comprised former MGP leaders. But then, Shashikala Kakodkar, who apparently had had enough of back-stabbing done to her, did something outlandish; in March 1980, months after she had quit, she announced that the MGP would merge with the Congress! This shocked the loyalists of her party who were hoping to hear words of encouragement from their leader on taking the MGP forward. It’s clear that Shashikala Kakodkar was in no mood to fight it out, and to this end she was willing to cause the demise of the party her father had founded. She did join the Congress with a bunch of her die-hard supporters. She got very little from her new party, sought a return to the MGP, was denied the opportunity, formed her own outfit, but finally made it back home. But by then, both she and the MGP had lost credibility among the masses.

Had the MGP played its cards well and not committed harakiri, it could have seized upon the opportunity that came its way in 1989, when the Rane-led Congress Government was formed with a wafer-thin majority. Months later, the Congress split (meanwhile, the non-Congress regime of VP Singh had taken charge in New Delhi) and the rebels walked off to create a new outfit, the Goan People’s Party. The MGP became one of the coalition parters in the new alliance Government, but it was not the dominant one. More for old times’ sake than in recognition of her political heft, Kakodkar was made a Minister. That Government soon fell, but the MGP never managed to exploit the situation and regain to its old glory. Finally, after her defeat in a 2002 Assembly election, Shashikala Kakodkar withdrew from active politics.

Meanwhile, as the MGP continued to decline and vacate political space, the BJP scripted its entry. Led by Manohar Parrikar and Shripad Naik (both Union Cabinet Ministers today), the party aligned with the MGP and slowly took over its vote-base. To this, the BJP added its own vote bank of upper caste Hindus. Parrikar’s across-the-community acceptability and Shripad Naik’s cheerful persona brought dividends for the party over the years, beginning with the mid-1990s. Slowly but surely, the BJP occupied all the space the MGP had ceded and ended up becoming a stronger challenger to the Congress than the MGP had been. The rise of the BJP and the simultaneous decline of the MGP can be gauged by the fact that, over the last few years, the latter had been a junior partner to the BJP in State politics. In fact, the MGP would have been in even more dire straits today had it not broken ties with the Congress in 2012 and aligned with the BJP. It remained afloat then and continued its partnership until recently when it went with Subhash Velingkar’s outfit. It does appear that the MGP has yet again taken a wrong political call— partnership with the Congress was among the others.

The case study as it were, of the rise and fall of the MGP has political relevance even today, particularly in the context of the waxing and waning political fortunes of many of the regional parties currently dominating the political debate. Looking backat the MGP, a few conclusions are inevitable. The first is that, however strong a regional party may be, it can be destroyed by the overwhelming ambition of individual leaders who see their interests as dominating that of the outfit which nurtured them and helped them grow. It’s a lesson that is currently apt for the AIADMK, where the tussle for power is threatening to reduce the regional party into a has-been. The second is that leaders must not throw in the towel in the face of adversity. Had Shashikala Kakodkar not acted in haste but quietly retreated to rebuild the organisation, the MGP would have made a comeback in 1989. A study in contrast are Mayawati, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa. All these regional leaders faced setbacks but bounced back stronger. They never lost focus. The third conclusion is that, if the leader himself/herself abandons the party, then the party may as well fold up. The MGP of today, for instance, is unrecognisable from that of Bandodkar’s or even Shashikala Kakodkar’s party — having been taken over by turncoats and people with dubious merit. The fourth is that one must change with the times. The MGP never managed to expand its voter base beyond its traditional vote-bank. It could never, for instance, secure the trust of the minorities, which despised its pro-Marathi and pro-Maharashtra tilt. Even the BJP under Parrikar’s leadership and with all the RSS baggage, achieved what appeared to be an impossible task — winning over the sizeable Christian population. And finally, a regional party must not lose sight of its bread and butter, which is, promoting the regional aspirations of the populace it seeks to represent. The MGP, since the 1980s, lost that plot, giving rise to a host of smaller regional outfits which, while they did not do well, ended the MGP’s dominance as Goa’s pre-eminent regional force.

The results of the ongoing state Assembly elections will have to be studied closely since some of the major regional parties such as the Akali Dal, Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party etc. are in serious contest to maintain their supremacy and relevance. What would happen to AIDMK is a different matter altogether.

(The writer is Opinion Editor, The Pioneer, senior political commentator and public affairs analyst)

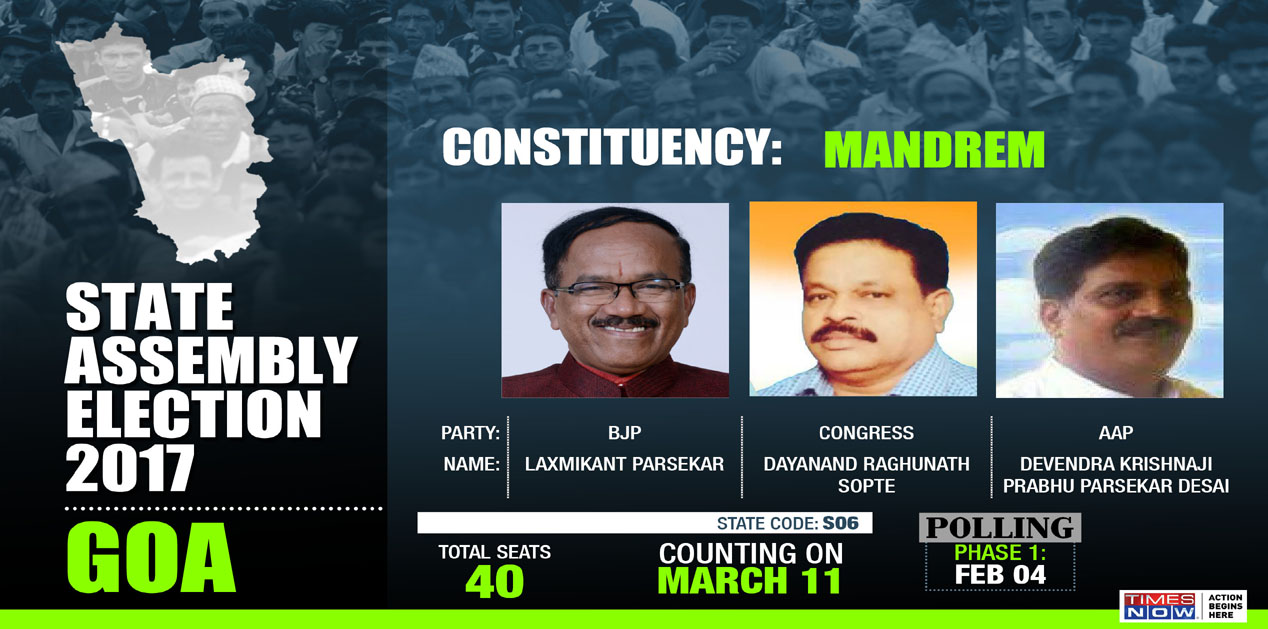

Published Date: 14th February 2017, Image Source: http://www.timesnow.tv

Post new comment