Parliament has just approved the vote on account and remitted the Budget proposal to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance. The expenditure proposals will be considered by the individual ministries to whom the Demands for Grants pertain. The taxation and other tax related proposals will be examined by the Standing Committee on Finance. Both these would now be considered for final approval with such modification as the Finance Minister considers appropriate post the Parliamentary Recess period. These both would be approved and concluded in the first half of May. This will conclude the Budget Session. The Budget is essentially divided in three parts- first, which deals with the overall macroeconomic policies and behavioral pattern of key macroeconomic indicators; second, which deals with the proposed expenditure outlay of the central government and the third, which deals with the tax proposals.

On the first issue, this year it has generally been accepted that the Budget represents a credible balancing act and has given a decisive momentum to the new economic upturn which has commenced. What were the key policy options before the Finance Minister? How have these choices been exercised?

One, the classic choice: Growth versus Inflation. How much of fiscal flexibility was acceptable to enhance public outlays in infrastructure – railways and highways? The budget has adhered to the path of fiscal rectitude by meeting the fiscal deficit target of 4.1% this year. It has stretched out by a year the terminal fiscal path to reach the 3% target with somewhat higher intermediate targets. The rating agencies prefer a closer adherence to the fiscal roadmap. As compared to his predecessor, however, the Finance Minister has not pushed any Pause Button even after accepting what the analysts perceived to be the unrealistic target of 4.1% this year. Of course, the new fiscal time path must now be adhered. I have for long argued that parliamentary approvals on changes in the Fiscal Roadmap must be ex-ante than ex-post. Besides, the recommendation for the constitution of a Fiscal Council contained in the Finance Commission’s recommendations is sensible and should be considered in future. This along with the new Monetary Policy Framework Agreement between the Finance Ministry and the Reserve Bank of India would act in congruent ways. It will ensure harmony between monetary and fiscal policy.

Second, has enough been done to rationalise subsidies? There are significant gains in rationalising petroleum and fertilizer subsidies by de-regulating petrol and diesel and moving over to the Aadhar based LPG subsidy. Further action is needed on fertilizers, particularly Urea. There must be pari-passu progress as JAM (Jan Dhan-Aadhar-Mobile) gathers momentum.

Third, exogenously, oil prices have declined from $82 to $59, commodity prices have also softened and the current account deficit moderated. This opportunity could have been used to create greater fiscal space by retiring public debt or creating a Consolidated Sinking Fund for debt amortisation. The Finance Commission suggests this can “tide over, roll over risks and the weak cash management practices”.

However, a middle path has been preferred. Substantial benefit passed on to the consumers enhancing their purchasing power, oil companies allowed to recoup some losses and the Centre enabled to raise revenues to meet fiscal targets. Given the opportunity, some of the options mentioned above must be pursued.

On the second broad theme of the Expenditure Budget, the overarching considerations were the recommendations of the Fourteenth Finance Commission (FFC). The FFC has made far reaching changes in the model of Fiscal Federalism. The key features of the FFC were the enhanced devolution from the divisible pool of taxes and the change in formula which decided the sharing of taxes and grants among the states. Let us examine some overarching points associated with the FFC’s recommendations.

One, there is overwhelming precedence that on devolutions they have been treated as awards than recommendatory.The rise in tax devolution to States and the Non Plan grants to local bodies together represent a sharp cut of Rs. 214442 crore from the Centre’s resource block. In the shrunken resources for the Central government, the funding pattern of schemes has undergone a structural shift. Having accepted the recommendations, the Government had limited options. It could either significantly relax the fiscal consolidation programme to finance all central and centrally sponsored projects as before or could find a different mix. Relaxing the Fiscal Roadmap further would have serious consequences.

The Budget at a Glance highlights the middle path. It classifies Public Expenditure in three categories– schemes to be supported by the Union, schemes to be continued with change in sharing pattern and those fully de-linked from Central support. The major flagship programmes of the government remain in the Union list like the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, MGNREGA and National Health Mission. There are others which fall in the second category. Schemes de-linked from Central support are rather small, the most contentious being the Backward Region Grant Fund.

Two, in concluding the reduction of outlay on key social areas, some methodological errors have crept in. Perhaps, the Budget Expenditure (BE) of 2015-16 is being compared with the BE of 2014-15. This is never done because we have to always compare Revised Expenditure (RE) of the previous year with BE of the current year. Such comparison would suggest that allocations have been kept more or less intact. In the case of Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), the reduction is sharp, but the pattern of funding is yet to be decided.

Three, in deciding whether the states have gained or lost their share in devolution from the Centre, one shall take into consideration the absolute gains or losses in the transfers than being bothered about the percent share. The Economic Survey released on February 26, 2015 well explains how each state will benefit in absolute terms. Thus, withdrawal of any grants or reduction in percentage share is aimed to reduce inter-state fiscal inequalities. In the long run, a progressive re-allocation of resources could promote fair and equitable growth.

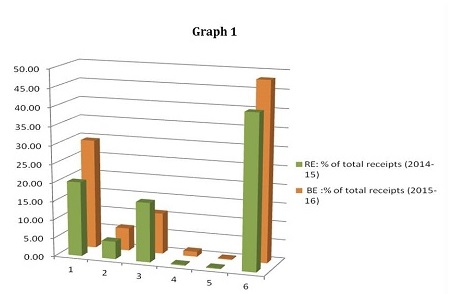

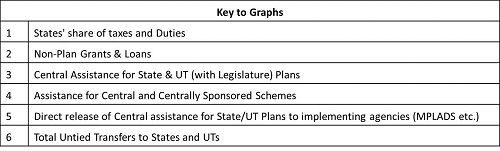

Four, the report represents a quantum shift from an earlier period when a lot of the devolution took place through centrally sponsored schemes and schemes which were settled to the prevalent predilections and the policy preferences of the Central Government. The amount of untied funds transferred to the states have increased from Rs.696951 crore i.e. 62 % of revenue receipts to Rs.865185 crore i.e. 75 % of revenue receipts. The Graphs (1 & 2) below indicate show a comparison of transfer of untied funds from Centre to States. The FFC assigns the States more important obligations of deciding the welfare of their people and the path for their development. Complete decentralisation is anyhow not envisaged by any management text. States gain not significantly from the additional resources but more so from the flexibility they now have in conception, design and implementation of projects best suited to their local needs.

Five, the enhanced power to the states implies greater accountability and answerability on the part of the States. The States can decide their priorities, choose their preferred model of development, exercise tradeoffs on policy options. More broadly, States can devise their Production Possibility Frontier and their ‘Development Possibility Frontier’ and become accountable directly to the people. Besides putting Fiscal Federalism in operation, this also tends to promote Competitive Federalism. However, competition while promoting innovation and efficiency also brings forth the non-viability of the inefficient players. Hence, a mechanism to enhance and support governance in such states beyond providing monetary resources is important to promote equitable growth across states.

Six, allocation of funds from the Centre to States in India is dictated by Five Year Plans. The FFC was constituted and its recommendations leading to change in the pattern of funding of Centrally Sponsored Schemes, accepted in the middle of the Twelfth Five Year Plan. There remains an uncertainty on devolution of funds from Centre to the States pertaining to certain schemes covered under the Twelfth Five Year Plan. A path addressing the issue that how would the transfers be transitioned from being in accordance to XIII FC’s formulae to be in parlance to XIV FC’s. Designing a satisfactory transition path like a mid-term review of the Twelfth Five Year Plan or any other would remain a challenge for North Block and the NITI Aayog. For a better alignment of the Five Year Plans (if they are to be continued) with the successive Finance Commissions, it would be essential to align the 5 year term of the FYPs and the approved recommendations of the Finance Commission.

On the third issue of tax proposals, the tax rates are by and large kept stable. On the indirect tax side the decisive change will come with the implementation of the GST hopefully from 2016. This will make India a large common economic market, eliminate cascading impact, enhance revenues and create growth multipliers. Given the enormous work involved, there is some scepticism on adherence to the time frame.

Second, on the Direct Taxes, India’s high corporate tax rates detracted new investments, domestic or foreign. Its reduction by 5% over the four years is positive, though the time path is opaque. Individual tax rates have remained unchanged and stable but some new cesses have been added for Higher Secondary Education and could be imposed to support Swachh Bharat initiative.

The problem in general with Direct Taxes is its narrow base. Leaving out agriculture sector as a whole shrinks the tax base significantly. While poor farmers must be spared, the use of agricultural income as tax shelters by rich agriculturalists needs fresh consideration.

Third, on retrospective taxation the budget has reiterated the commitment that it would be avoided in future. GAAR has been put in the cold storage since on many issues like base erosion, profit sharing, treaty shopping, tax arbitrage consensus on best international practice is yet to emerge.

Finally, the Budget and the FFC as Two Sides of the Same Coin.

In the current era of globalisation, a growing incongruity in terms of GSDP, per capita income, tax base, population etc. among the States, heterogeneity in patterns of governance, rise of regional parties and increased global interdependence represent contemporary challenges to the dynamics of Centre-State relations. Thus the need to restructure Centre-State relations has gained recognition over recent past. This concern was voiced by the successive State Governments. The centrepiece of the complaints was the inflexibility and the predetermined project design and conditions of the Centre. The FFC was generally welcomed as a solution but the Budget has left some States and stakeholders critical based on inadequacies of allocation in the social sector.

The FFC has designed a new financial architecture of Centre-State relations. The Government had little option given the shrunken envelope after accepting the Finance Commission’s recommendations. After all you cannot have the cake and also eat it. States cannot have both the cake of large untied resources and eat the Centrally Sponsored Schemes as originally conceived. One can argue of whether this was the best approach or could the recalibration have been somewhat different.

Will this new model of Fiscal Federalism work? There are inherent risks but also existing opportunities for Team India. The risks are well known if the State Governments act irresponsibly or promote fiscal profligacy. But in the end, the Government at the Centre and the States are judged by the improvement and development of life quality by the Electorate whose periodic mandate they seek.

The new fiscal architecture eliminates the form of neo-colonialism like what Rudyard Kipling described as the White Man’s Burden viz. the Centre knows what was good for the States. A new social compact between the Union and the states has been ushered.

In the end, as said by Francis Bacon- “Demonstratio longe optima est experientia. By far the best proof is experience.”

(The author is a noted economist, former top bureaucrat and Ex-MP)

Published date: 31st March 2015, Image source: http://www.livemint.com

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Vivekananda International Foundation)

Post new comment