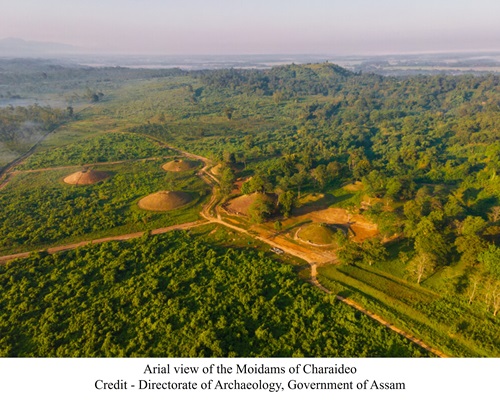

In Upper Assam’s Charaideo district on the foothills of the Patkai Ranges, amidst the vast expanse of greenery, one can find a place where the holy spirits reside, the Moidams. There are around 90 big and small dome-shaped earthen mounds in Charaideo, comparable to the pyramids. The Moidams are a unique form of burial mounds for the kings, queens and nobles of the Ahom Dynasty. The Ahoms, originally from the Tai ethnic group in Southeast Asia, brought with them distinct cultural practices to India, including their unique burial traditions. No other funerary structures found in other parts of India can be compared with the Moidams, which are distinct in their style and architecture. The Moidams of Charaideo is a window to the glorious history of the Ahoms dynasty established by the great Chau-lung Siu-ka-pha or Sukaphaa in 1228 CE. The Ahom rulers established a powerful kingdom in Assam that ruled over the Brahmaputra Valley for nearly 600 years. Their long reign provided political and cultural unity and gave economic stability to the region. On the 26th of July 2024, Moidams of Charaideo was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List, as India’s 43rd entry during the ongoing 46th session of the World Heritage Committee at New Delhi. [1] The recognition of the Moidams as a UNESCO World Heritage Site not only underscores their historical and cultural significance but also emphasizes the global acknowledgment of their value.

Moidams are also found in other eastern districts of Assam like Dibrugarh and Jorhat, but the Moidams of Charaideo are unique because it was the first capital of the Ahoms. The founder of the Ahom dynasty, Sukaphaa, was buried at Charaideo. After this, Charaideo became the necropolis of all the Ahom rulers and was considered a sacred place. The tradition of Moidams is deeply rooted in the Tai-Ahom culture, and the word Moidam originates from the Tai script ‘Phrang Mai’, which means to bury, and ‘Dam’, which means spirit of the dead. [2] The Tai-Ahoms believed that while the body perishes upon death, the soul lives on. Therefore, these burial mounds were constructed as monuments to honour the lives of the deceased. The Moidams around Assam are still worshipped by the descendants and the general population. The annual ritual commemorating the dead among the Ahoms is called Me-Dam-Me-Phi, which is an ancestor worship tradition of the Tai People, [3] celebrated annually on 31st January.

The outer façade of the Moidam is generally hemispherical in shape. The size of the Moidam varies from a modest mound to a small hillock, depending upon the influence and status of the person buried in them. According to the Chang-rung Phukanar Buranji (a historical chronicle and manuscript associated with the Ahom kingdom), the Moidams are made of five architectural elements, namely a Garvha (underground chamber where the mortal remains of the deceased are placed), a Tai (vault), Ga-Moidam (the body of the Moidam which includes the earthen covering over the vault), Chaw-chali (a temple-like open pavilion at the top for the annual offering), and a Garh (a small octagonal boundary wall around the base made of stones) with an arched gateway to access the inner chamber of the Moidam on one side. Between the 13th and 17th centuries, the Moidam inner vaults were made of wood. After king Rudra Singha (1696 CE-1714 CE), the inner chambers were made of stone and burnt bricks of various sizes. According to Chang-rung Phukanar Buranji, the bricks and stone blocks were joined with the help of a mortar mix consisting of lime, pulses, resin, hemp, molasses, fish, etc. However, there are many smaller Moidams, possibly of the nobles, that do not have all the aforementioned features and are crudely made of earth.

The construction of a Moidam is steeped in religious and cultural symbolism. The burial mounds are oriented in specific directions, and the placement of artifacts within the burial chamber follows meticulous rituals. The coffin of the royals was made of a specific type of timber called Uriam (Bescoffia javanica) [4] and was called Rung-dang. Elaborate rites were performed while placing the Rung-dang with the mortal remains of the Ahom king in the inner chamber. These rites lasted between six months up to two years. The Chang-rung Phukanar Buranji also elaborates on these crematory rituals of the Ahoms, which were performed with great pomp and grandeur, reflecting the hierarchy of the deceased. The kings were buried with artifacts made of gold and silver, such as ornaments, utensils and weapons. Most of the Ahom royals enjoyed having betelnut with tobacco and lime. Therefore, small clay pots with betelnuts, lime and tobacco were buried with the royals for the afterlife. Other daily-use artifacts like clay utensils, clothes and décor items were also buried with the dead. Archaeologists have even excavated cannon balls from some of the Moidams. After completion of the burial rituals, a raised rectangular platform was constructed over the burial, and the entrance to the chamber was sealed with mud stones and bricks. The earthen mound was constructed over the chamber in around three to four months. The mound was covered with a layer of bricks to protect it from erosion.

At Charaideo, there was a specific road to carry the dead bodies known as Sa-nia-ali (Sa means dead body, nia means carry, and ali means path or road) and a specific tank for the ritualistic baths of the death bodies, which is known as Sa-Dhua-Pukhuri (Sa means dead body, dhua means bath and pukhuri means tanks. [5] These practices are believed to ensure the safe passage of the soul to the afterlife. The Moidams also served as focal points for ancestral worship, reinforcing the connection between the living and their forebears.

The significance of the Moidams was recognized by historians and archaeologists as early as the 19th century. By this time, most of the Moidams had already been damaged by Mughal raiders, British looters and local treasure hunters. However, systematic efforts to preserve and study these mounds gained momentum only in the latter half of the 20th century. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), along with the Assam State Department of Archaeology, have played a pivotal role in documenting and conserving the Moidams of Charaideo, highlighting their historical and cultural importance.

The journey to UNESCO World Heritage Site recognition involved extensive research, documentation, and advocacy. Local historians, archaeologists, the Assam government and the central government collaborated extensively to prepare a comprehensive dossier that highlighted the historical significance, architectural uniqueness and cultural importance of the Moidams. The Moidams have been testimony to a significant period in human history. This dossier was submitted to UNESCO, and after rigorous evaluation, the Moidams were inscribed as a World Heritage Site.

The inclusion of the Moidams in the UNESCO World Heritage List will further boost the efforts to preserve these historic structures. It will also increase the funding for conservation measures, ensuring that the Moidams are protected for future generations. The recognition will also spur tourism in the region, bringing global visitors to explore the rich heritage of the Ahom Dynasty. Despite the significant strides made in preserving the Moidams, several challenges persist. The mounds are vulnerable to natural erosion, environmental degradation, and human encroachment. Ensuring their long-term preservation requires continuous monitoring, maintenance, and the implementation of sustainable conservation practices. The Moidams, with their rich historical, cultural, and architectural significance, represent an invaluable part of the heritage of the Ahom Dynasty, Assam and India. It is imperative to continue our efforts to preserve and protect the Moidams, ensuring that their legacy endures for future generations to appreciate and learn from.

References

[1] PIB, Ministry of Culture

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2037495

[2] Moidams at Charaideo, Assam State Portal.

https://sivasagar.assam.gov.in/sites/default/files/public_utility/Moidams%20at%20Charaideo.pdf

[3] Gogoi, Shrutashwinee (2011). Tai Ahom religion a philosophical study (PhD).

[4] Ahom Buranji

[5] Moidams at Charaideo, Assam State Portal.

https://sivasagar.assam.gov.in/sites/default/files/public_utility/Moidams%20at%20Charaideo.pdf

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/thumbs/site_1711_0005-1000-750-20240529155522.jpg

Post new comment