1. Introduction

The term 'migrant' is often stereotyped as a person who is an undesirable burden and their economic contribution to national economies is seldom measured. The correlation between migration and remittances can be understood as a result of a chain of development. It flows from individuals through to households, communities, and, ultimately, to the countries. For example, the remittances would enable a family to invest in a new home, which would indirectly contribute to the employment generation in the construction sector of a country. Remittances also increase the incomes of households and reduce the level of poverty, thus ultimately boosting the country’s GDP growth. Some migrants also get access to better quality education, health, and other social services, which help them, reduce child and maternal mortality rates.

Labour migration from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan to Russia and Kazakhstan, has provided political and socio-economic opportunities to the migrants as well their host countries. Russia and Kazakhstan provide millions of Central Asian migrant workers work opportunities they cannot find in their own countries. Mostly, these migrants have low paid jobs, which local people have rejected.1 With the outbreak of novel coronavirus, the closing of international borders became mandatory to limit the scope of the spread. Central Asian countries closed their physical frontiers with each other, and also borders with Russia which have typically been very open. As the number of cases of coronavirus increased in the Eurasian region, governments have also prohibited travelling due to lockdown measures. Concurrently, millions of migrants in diverse economic activities have lost their daily livings. The situation has become even worse as they were unable to reach their homes due to the various travel bans.

In the recent past, plunging oil production and prices in both Russia and Kazakhstan have severely affected these workers. After the depreciation of the Russian currency against the US dollar, it has become less attractive for labour migrants to work in Russia. Between February and March, a considerable portion of Central Asian migrant labourers working in Kazakhstan and Russia have returned to their homes.2 In its fight against COVID-19, Russia has closed many economic enterprises which largely employed the migrant labour from Central Asian countries. Due to quarantines and lockdowns, trade has plummeted to essential goods and services, though increasing the demand for courier services. A significant reduction has also been witnessed in hospitality, real estate, and other services. Earlier, many of the migrant workers could easily earn about 500 USD per month. Salaries have sharply declined now and are not sufficient to meet the living expenses of the migrants themselves; thereby, reducing the funds available for them to transfer to their homelands.3

2. Russian Response to Migrant Labour amidst COVID-19

Fear of Migrants Indulging In Criminal Activities

Russian authorities have been considerate of the problems faced by the labour migrants who have no money or social support amid the coronavirus pandemic. Many labour migrants were willing to return home, but due to the closure of state borders, they have had to stay back. Others still hope to make money in Russia to support their families at home. Labour migrants are more accommodative and quickly able to switch from one profession to another. Now, being out of money and job, a concern for Russian authorities is that migrant labour might get involved in criminal activities.

Work permits extended despite hit to state revenues

To ease the problems faced by the migrant workers, President Putin, on April 18, signed a decree which automatically extended the work permits, registrations, expired visas of foreign citizens, and other labour patents from March 15 to June 15. It also allowed for employers to reserve the right to employ persons with expired licenses or those without them. Law enforcement agencies are barred from taking any administrative action against such foreign nationals. In case the validity of provisional residence permits for foreign nationals staying in Russia gets expired, it will be extended automatically.

When the Russian government imposed the quarantine, migrant workers requested the authorities to revoke the payment for obtaining patents. As per the estimation of the Russian Federation, the payments made by the labour migrants to get these patents contribute almost 60 billion rubles to the Russian state budget per annum. In 2019, 463.7 thousand labour patents were issued to foreign citizens in Moscow city, which added about 18 billion rubles to the city’s revenues.4 Most of these patents were issued to the citizens of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are member countries of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU); therefore, workers from these countries are exempted from payment for labour patents. The citizens of EEU member countries have the status of ‘workers’ and not labour migrants, which provides a simplified procedure for stay and work compared to that of a labour migrant.

3. Problems faced by Migrant Workers

Stranded and Vulnerable

Migrant workers from Central Asian countries have been trapped at three different airports in Russia, after regular flights to Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan were stopped. Not only that but also hundreds of workers were stuck on the borders between Russia and Central Asia. In Orenburg city, more than 150 Kyrgyz workers were trapped on the border for three days. Stranded for days at the airports, these workers were sleeping on the floors and using unhygienic public utilities, which made them susceptible to the virus infection.5

No Job and Payments

In many Russian cities, thousands of labour migrants from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan were left without employment and livelihood. Some stayed back in these cities to collect money for their air travel back to home. Social welfare organisations supported a small number of these migrants with food and essentials. These organizations also appealed to the Presidents of the Central Asian countries to assist their citizens trapped in Moscow and other cities. With no jobs and payments, these workers were unable to send money back to their countries, which also severely affected their families amid the pandemic crisis.

No Option but to Return Home

Labour migrants from Central Asia mainly work in trade, services, and construction sectors in Russia and Kazakhstan. Most of these enterprises are closed, causing panic amongst migrant workers to return to their homes.

Poverty and unemployment are quite prevalent in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which lead to labour migration. Also, the lack of quality jobs and limited wages is another significant factor causing excess labour outflow from Central Asia to other countries. Remittances cause dependence not only among the population but also for the overall country's economy. Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, parts of labour migrants returned to Kyrgyzstan and have decided to spend these difficult times with their families as they do not have an option. It is believed that this will lead to an economic collapse in the region due to high rates of unemployment.

Spring Wave of Migration is Ruined

Every year, from late March to the end of April, is considered to be the peak season for many Kyrgyz and Tajik migrants to depart for Russia. Some of them travel by air, while vast numbers of people opt for cheaper options such as travel by trains or buses. However, traveling by trains and buses takes a long time as several days are spent passing through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. With the new coronavirus outbreak, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have shut down their borders which have created uncertainties for these migrant workers waiting to get to Russia.6

4. Impact on the Migrant Sending Countries

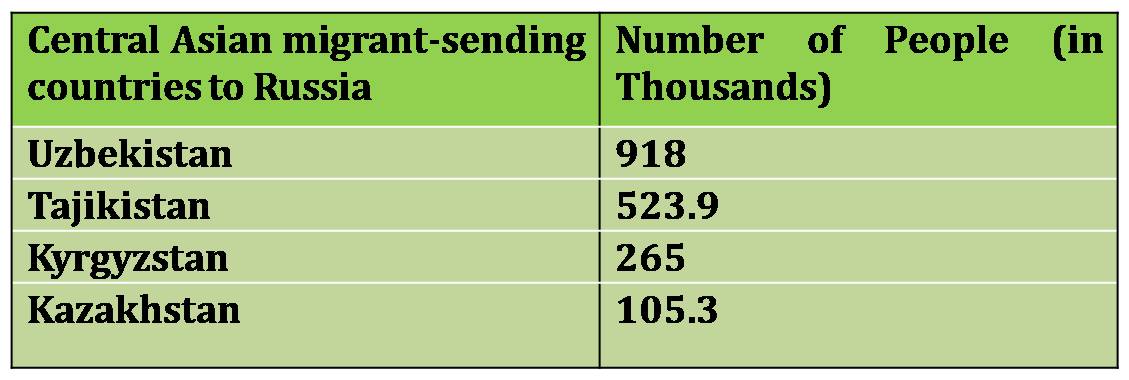

Spread of COVID-19 has caused significant damage to the remittance based economies of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. In 2019, migrant workers from Central Asian republics had sent approximately 8 billion USD to their respective countries. Last year, when the border service of Russia’s Federal Security Service commenced tracking the number of foreign nationals entering the country in search of employment, the majority of them were from Central Asia. In Russia, there are almost a million migrants from Uzbekistan, over half a million from Tajikistan, 265 thousand from Kyrgyzstan, and around 100 thousand from Kazakhstan.7

In order to understand the pattern of migration in these countries, it is essential to look at the ratio between the population and migrant workers. The population of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan are 9.5, 6.5, and 33 million, respectively; therefore, the impact of remittances on the economy of these countries also varies. Remittances from migrants are the key support of the socio-economic and political life of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which are the two poorest post-Soviet republics in the region.8

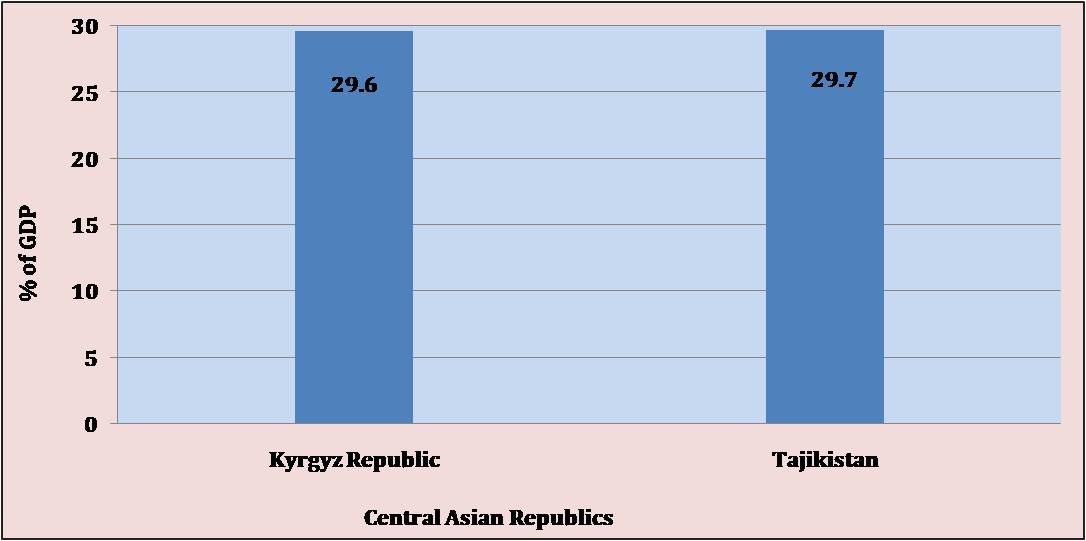

The extent of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan’s reliance on Russian remittances is understandable when these numbers are compared with the overall economy of these countries, which is 29.6 percent for Kyrgyzstan and 29.7 percent of GDP for Tajikistan in 2019. These figures were higher before the Russian economic crisis of 2014 when due to the sanctions; exports of oil and gas were declining.9

5. Conclusion

Due to lack of economic opportunities in their homelands, people from Central Asian countries migrated to Russia. These migrant workers are prone to economic changes in their host countries. The socio-economic helplessness of these workers is evident during the ongoing Pandemic crisis. Apart from the financial consequences of the migrants’ problem, social protection and mental well being are also at risk at this point of time. Cases of domestic violence have increased due to the lockdown. Shortage of food and other essentials have also added to the already struggling Central Asian households. People trapped in their houses are out of money and are unable to fulfil the daily needs of their families. Therefore, they go out in the local markets in search of jobs that expose them to the infection of the coronavirus. Respective governments need to come up with concrete solutions to overcome this emergency along with ensuring safety and wellbeing of migrants’ households. However, food security and maintaining health care system should be the prime concern of the Central Asian regimes amidst the pandemic crisis. To an extent their situation could be compared to what is happening in India about migrant labour crisis; possibly there are lessons to be learnt from both situations.

Endnotes

- International Crisis Group, Central Asia: Migrants and the Economic Crisis, Asia report No. 183, Europe & Central Asia, 5 January 2010. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/central-asia/kazakhstan/central-asia-migrants-and-economic-crisis

- ‘Tajikistan says migrants returning from Russia, Kazakhstan’, World news, reuters, 17 April 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-tajikistan-economy/tajikistan-says-migrants-returning-from-russia-kazakhstan-idUSKBN21Z19H

- Maria Levina, ‘Labor migrants from Central Asia: no earnings, no social support, The times of Central Asia, 23 April 2020. https://www.timesca.com/index.php/news/26-opinion-head/22393-labor-migrants-from-central-asia-no-earnings-no-social-support

- Ibid.

- Aruuke Uran Kyzy, ‘Coronavirus Exposes Central Asian Migrants’ Vulnerability’, the Diplomat, 10 April 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/coronavirus-exposes-central-asian-migrants-vulnerability/

- Farangis Najibullah, ‘Tajik Workers Face Dire Future As Russia Closes Borders Over Coronavirus’ RFE/RL Tajikistan, March 18, 2020. https://www.rferl.org/a/tajik-workers-face-dire-future-as-russia-closes-borders-over-coronavirus/30495815.html

- Maria Levina, ‘Labor migrants from Central Asia: no earnings, no social support, The times of Central Asia, 23 April 2020. https://www.timesca.com/index.php/news/26-opinion-head/22393-labor-migrants-from-central-asia-no-earnings-no-social-support

- ‘Coronavirus: Central Asia Labour Migrants In Crisis Russia’s economic woes will have a major knock-on effect in the region’, IWPR Central Asia,30 March 2020. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/coronavirus-central-asia-labour-migrants

- Sam Bhutia, ‘Russian remittances to Central Asia rise again When Russia hurts, Central Asians feel the pain. Are remittances a boon or a bane?’ The Eurasianet, May 23, 2019. https://eurasianet.org/russian-remittances-to-central-asia-rise-again

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://bloknot.ru/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/migranty-nalogi.jpg

Post new comment