The knife terror attack on 02 February 2020 in Streatham High Road in London, United Kingdom (UK) brought back memories of a similar terror incident on the streets of London on 29 November 2019 in which a Pakistan-origin British national—Usman Khan, in his late twenties, stabbed two people to death and injured three others at the London Bridge, in Central London,1. And now, less than two and a half months later, a convicted terrorist but released on licence or parole— Sudesh Mamoor Faraz Amman, (20 years), carried out a knife terror attack on the Streatham High Road in London, severely injuring two people before being shot dead by the security personnel.2

The very next day, on 03 February 2020, Islamic State (IS) described Sudesh Amman as a “fighter of IS” and claimed responsibility for the terror attack (Amaq agency).3 Similar to the November 2019 attacker— Usman Khan, Sudesh Amman was also on licence/parole from jail, released in late-January 2020 after serving only half of his imprisonment term for terrorism offences in 2018. It may be recalled that in May 2018, Sudesh Amman was arrested by the UK police on suspicion of conspiring a terrorist attack in London. On 07 November 2018, Sudesh Amman was found guilty on six counts of possessing a document containing “terrorist information” and seven counts of disseminating “terrorist publication”4 which could be a useful material for a terrorist. At the age of 18, in December 2018, Sudesh Amman was sentenced to imprisonment of three years and four months, but under the existing Automatic Prisoner Release Policy, he was freed after serving half of his sentence and kept under “special” surveillance by the police on suspicion of being of high-risk for the society. 5

Who was Sudesh Amman?

Raised in Harrow, a predominantly Muslim dominated suburb in the North-West London, Sudesh Amman lived with his Sri Lanka-origin Mother— Haleema Faraz Khan (41-years). In his school days, Amman showed no signs of inclination towards extremism. Being a student of science in college days, Amman wanted to pursue biomedical science in higher studies, said Haleema Faraz Khan. It was claimed by his mother that Sudesh Amman was radicalised while under confinement in the “high-security” prison by watching Islamic extremist material online.6 Sudesh Amman used to share his extremist ideology and al-Qa’ida propaganda with his friends, immediate and distant family members through WhatsApp groups. In one of his text messages to his girlfriend, Amman told her:7

“If you can't make a bomb because family, friends or spies are watching or suspecting you, take a knife, Molotov, sound bombs or a car at night and attack the tourists (crusaders), police and soldiers of taghut, or Western embassies in every country you are in this planet.”

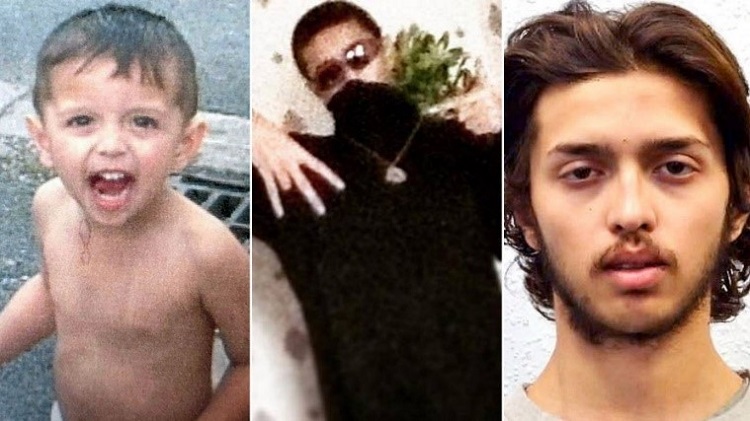

Image 1. Sudesh M F Amman photographed from childhood to 2018 [credit: Sky News UK]

In April 2018, a Dutch blogger came across some online material posted in a Telegram chat room dedicated to Islamist extremism. The material, uploaded thereon, consisted of a photograph of a knife with two firearms on a Shahada (or ‘faith’— one of the five pillars of Islam religion) flag with the phrase ‘Armed and ready April 3’ in the Arabic language. 8 A trail of investigations of the chat room revealed that the material was posted through Sudesh Amman’s account— @strangertothisworld and further investigation on this led to his arrest. At the time of his arrest in May 2018, Sudesh Amman was a student of Science and Maths at the College of North West London, in the UK. In 2017, Sudesh Amman at 17 years of age started collecting material propagating Islamist extremism. The same year he was convicted for possession of cannabis, low-grade weapon, sharing of graphics and videos of terrorists online, manuals of bomb-making and knife attacks.9

Upon his arrest in 2018, police forensic specialists seized digital devices for forensic analysis. They recovered more than 349,000 media files, including manuals of combat training, techniques of stabbing and bomb-making. 10 As a remarks in Amman’s conviction report in 2018, then Head of the Metropolitan Police Counter Terrorism Command and Acting Commander Alexis Boon recalled that in Amman’s notepad (recovered during the raid in his house) — his fascination to attain martyrdom in the name of terrorism and going to “Jannah” which meant that the “afterlife” concept in Islam were listed as priority under the heading of “life goals”.11

The Streatham Incident

As mentioned earlier, in the afternoon of Sunday, 02 February 2020, Sudesh Amman— a convicted terrorist but released on parole, stabbed two people to severe injuries in a knife terror attack on the streets of Streatham High Road area in London. Considering Amman as a threat and likely to be a re-offender of terrorism, he was kept under surveillance after his release from jail in late-January 2020. On the day of the attack, Amman, wearing a fake explosive vest, ran into a shop located on Streatham High Road and picked up a knife from one of the racks. Not realising that the knife had a safety cover on, he went up to the payment counter and tried to stab a woman standing there. Frustration with the unsuccessful attempts of stabbing, he went outside the shop and stabbed two people (causing injuries to them) before he was shot dead by the undercover police officers who had been doing surveillance on him.12 Witnesses, including the first victim inside the shop, described the incident of 15-20 mins as ‘a quick movie scene’.

Automatic Prisoner Release Policy— A “Failed” Policy

In one of my earlier publications at the VIF (Vivekananda International Foundation)13, the event of the November 2019 London Bridge Attack and gaps in the UK’s Automatic Prisoner Release Policy were analysed. It was then predicted that in the absence of serious considerations for a major reform in the policy, particularly the Automatic Prisoner Release Policy, and other terrorism offences related regulations, keeping the UK safe from terrorist attacks originating from its own soil, would be quite challenging for the UK’s security forces and intelligence services.

On the very next day of the attack i.e. on 03 February, the UK government emphasised on the re-introduction of an “emergency” legislation to end the Automatic Prisoner Release Policy for terror offenders. The UK’s Justice Secretary—Robert Buckland told Member of Parliaments (MPs), "We cannot have the situation, as we saw tragically in yesterday's case [Streatham terror attack], where an offender who was a known risk to innocent members of the public, was released early under an automatic process of law without any oversight by the Parole Board.”14 In other words, under the new emergency legislation, terror offenders will serve at least two-thirds of their given sentences, and they will not be released without a risk assessments being conducted by the Parole board.

What Lies Ahead?

The knife terror attacks carried out by Usman Khan in November 2019 and by Sudesh Amman now, have raised questions on the sentencing of terrorists in the UK. At the time of the Streatham terror attack, Sudesh Amman was said to be under surveillance of law-enforcement agencies. For how long Amman was under close surveillance and was there a possibility for officers to intervene before he carried out the attack? Keeping someone under surveillance is not a routine exercise to carry out. As per the laid down procedure, the Metropolitan Police’s senior officer is required to authorise “direct” surveillance in any public place. A signed warrant from the Home Secretary is a mandatory document for more stringent surveillance of an individual.15

Since the lone-wolf terror attack carried out on the streets of London in 2017, UK Lawmakers are perceived as exhibiting lack of “will-power” to initiate a strong policy of reform including changes in the existing Automatic Prisoner Release Policy, with a view to restricting terrorist offenders from committing further terror attacks. In both the terror incidents (November 2019 London Bridge attack and February 2020 Streatham terror attack), although the perpetrators had no prior connection with each other, the modus operandi, ideology, and the recourse to the provisions of the Automatic Prisoner Release Policy, were some of the factors in common. Neither the existing legislation nor the police officers on surveillance duty were successful in preventing the London Bridge attack or Streatham terror attack. Would the new emergency legislation be effective in preventing terror offenders from committing further terror attacks while being radicalised within the walls of well secured prisons in the UK? Only time will tell.

References

- Anurag Sharma. “London Bridge Attack: An Islamic State-inspired Knife Terror Attack”, Vivekananda International Foundation, 12 December 2019, Available from: https://www.vifindia.org/2019/december/12/london-bridge-attack-an-islamic-state-inspired-knife-terror-attack

- “Streatham attacker named as Sudesh Amman”, BBC News, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51351844

- Yaron Steinbuch. “ISIS claims responsibility for London stabbing attack”, NewYork Post, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://nypost.com/2020/02/03/isis-claims-responsibility-for-london-stabbing-attack/

- Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. R. v. Sudesh Faraz Amman- Sentencing Remarks (United Kingdom: Central Criminal Court, 2018), 1, Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/R.-v.-Sudesh-Mamoor-Faraz-AMMAN-sentencing-remarks.pdf

- Vikram Dodd, Dan Sabbagh, and Rajeev Syal. “Streatham attacker freed from jail days ago after terror conviction”, The Guardian, 02 February 2020, Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/feb/02/streatham-attacker-was-released-terror-offender-sudesh-amman

- Danny Boyle. “My son the Streatham terrorist”, The Telegraph, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/02/03/monday-evening-news-briefing-son-streatham-terrorist/

- Charles Hymas. “Sudesh Amman: the man who shared his chilling doctrine of hate with family and friends since his teenage years”, The Telegraph, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/02/02/sudesh-amman-17-year-old-student-became-terrorist-shot-police/

- Jorge Flitz-Gibbon. “London stabbing attacker identified as Sudesh Amman, ex-con with terrorist record”, New York Post, 02 February 2020, Available from: https://nypost.com/2020/02/02/london-stabbing-attacker-identified-as-sudesh-amman-ex-con-with-terrorist-record/

- David Mercer. “Streatham terror attack: What we know about Sudesh Amman”, Sky News, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://news.sky.com/story/streatham-terror-attack-what-we-know-about-sudesh-amman-11925200

- Ibid.

- Naomi Canton. “Streatham attacker Sudesh Amman has family in Sri Lanka and was under police surveillance”, The Times of India”, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/uk/streatham-attacker-sudesh-amman-has-family-in-sri-lanka-and-was-under-police-surveillance/articleshow/73887005.cms

- “Streatham attack: Sudesh Amman tried to stab me”, BBC News, 04 February 2020, Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51375908

- Anurag Sharma. “London Bridge Attack: An Islamic State-inspired Knife Terror Attack”, Vivekananda International Foundation, 12 December 2019, Available from: https://www.vifindia.org/2019/december/12/london-bridge-attack-an-islamic-state-inspired-knife-terror-attack

- “Streatham attack: Emergency terror law to end early prisoner release”, BBC News, 03 February 2020, Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51364047

- Nick Hopkins. “Questions for investigators over surveillance of attacker”, The Guardian, 02 February 2020, Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/feb/02/streatham-attacker-police-surveillance-monitored

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://c.pxhere.com/photos/ef/0c/knife_stabbing_stab_kill_murder_man_murderer_isolated-1341086.jpg!d

Post new comment