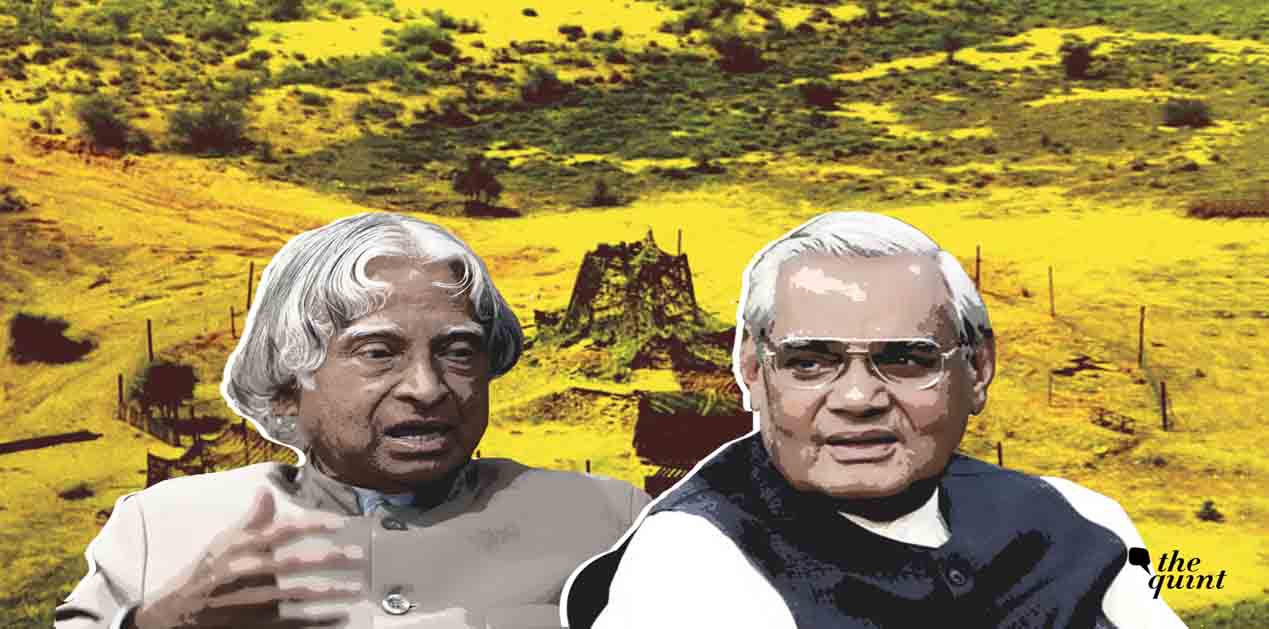

On 11th & 13th May 1998, India surprised the world by conducting five nuclear tests in the Pokhran deserts of Rajasthan.1 The tests marked the end of India’s long ambivalence vis-à-vis the nuclear weapons and set it on a path of nuclear deterrence as a sixth nuclear weapon power in the world.

Although the international community strongly censured New Delhi for its defiance of global non-proliferation norms and imposed wide-ranging economic sanctions, in the hindsight, the tests opened-up a unique diplomatic opportunity for India that paved its gradual integration into the global nuclear order.2 Post-1998, the Indian diplomacy not only succeeded in assuring the world about its responsible nuclear behaviour but also safeguarded country’s core strategic interests amidst the deteriorating regional and global security environment. More importantly, the tests enabled India to transform relations with the US and engender a historic shift in the bilateral ties. In retrospect, therefore, India’s decision to conduct nuclear tests and to proclaim itself as a de-facto nuclear weapon power seems to have served its interests quite well.

A Look Back

The two decades of India’s nuclearisation narrates an interesting story of its successful engagement with the global non-proliferation regime. If the first decade was all about convincing the world of its impeccable non-proliferation credentials and seeking an accommodation with the global regime; the second decade shows New Delhi successfully carrying out nuclear diplomacy to consolidate its presence in the global nuclear governance. Though largely unexpected, the single most important outcome from 1998 tests came in the form of ‘Indo-U.S. nuclear deal’ which called for India to “acquire the same benefits and advantages as other such (nuclear weapons) states”.3 Signed in 2005, the ‘nuclear deal’ not only brought India into the global nuclear mainstream but also opened the gates of technical aid to its industry and various high-technology programmes.

The deal particularly proved to be a great boon for India’s civil nuclear industry which suffered for long due to acute constraints of technology and fuel supplies. Besides, it also paved the way for India’s entry into the multilateral export control group which regulates the global trade in high-technologies and strategic goods.4 By January 2018, India has already become a member of entities like the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Australia Group, Wassenaar Arrangement and has stepped-up efforts to become a member of the last remaining entity i.e. the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). Similarly, at the strategic front, New Delhi has made impressive advances toward deploying a nuclear triad of land, air, and sea-based assets in keeping with the objectives of its doctrine which is to build a ‘Credible Minimum Deterrence’ (CMD) and maintain an ‘Assured Second Strike Capability.5

The accrual of such impressive diplomatic and strategic gains can be best explained by the paradigmatic shift that nuclear tests brought out in India’s attitude toward the international security architecture. The fall of the Soviet Union and the ensuing shift in the global balance of power necessitated that India develops a ‘strategic deterrent’ and guard against any potential ‘nuclear blackmail or intimidation’. The nuclearisation ushered in a much-needed shift in India’s foreign policy thinking wherein New Delhi learned to manage the global power dynamics and negotiate its core interests amidst the great power rivalries. The nuclear deterrent not only granted India a sense of security but also enabled its transition into a stronger and self-assured nation capable of pursuing its enlightened national interests.

Secondly, the nuclear tests also considerably changed India’s attitude towards the global non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament regimes. Traditionally, India remained one of the strongest votaries of ‘general’ and ‘complete’ disarmament and in advancing its disarmament campaign, it paid scant attention to non-proliferation and arms control issues. Post-1998, however, India became more supportive of the prevailing non-proliferation order which emphasised on arms control as a critical pathway towards the elimination of nuclear weapons. As a sign of change, India extended a strong support to arms control through the endorsement of the NPT objectives, showing readiness to join FMCT, seeking membership of export control groups, and actively participating in the nuclear security summit process.6 Similarly, post-nuclearisation India also embarked on a dialogue process with Pakistan, and the two countries agreed on a host of Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) during the historic Lahore Summit held in February 1999.7 The process of CBMs, however, ended abruptly and no new measures could be negotiated due to Pakistan’s reckless military adventure in the Kargil and the war that followed in the summer of 1999. The two decades of nuclearisation, thus, shows New Delhi successfully carrying out a diplomatic campaign to bring itself in alignment with the global non-proliferation regime.

A Look Ahead

In the last decade, however, India has come to face several new challenges in the global and regional nuclear environment. At the global level, the failure of two successive NPT review conferences coupled with the lack of progress in U.S.-Russia arms control and the failure of the Conference on Disarmament (CD) to adopt new work programme has created much uncertainty for the future of arms control and disarmament. This is further compounded by the collapse of ‘great power consensus’ which is brewing much trouble for the international non-proliferation system. Amidst the environment of uncertainty, the foremost challenge before India’s nuclear diplomacy is to further country’s integration into the global nuclear order and to secure the membership of the last remaining export control group, i.e. the NSG.

The NSG membership has proved to be relatively difficult for India due to China’s consistent opposition to its admission on the grounds of its non-NPT status.8 China’s deliberate disregard of India’s five-decade-long exceptional non-proliferation credentials and its insistence on forging common criteria to admit non-NPT states is causing a lasting damage to the norms of the global non-proliferation regime. To the credit of Indian diplomacy, however, more than three-fourths of the 48 NSG members have publicly acknowledged India’s commitment to the global nonproliferation and support its entry into the NSG.

As India reaches out to the remaining hold-outs on the NSG membership, India can further showcase its commitment to disarmament by extending support to new measures like nuclear risk reduction and global No-Fist-Use (NFU), besides reiterating its voluntary moratorium on nuclear testing. In the past, especially in the 70’s and 80’s, India was at the forefront of disarmament campaigns through proposals like time-bound action plan, nuclear weapon’s convention, freeze proposals etc. In the current context, India may well consider reviving some of the old ideas and seek wider support base for its proposal on ‘nuclear weapons convention’ beyond traditional supporters like the Non Alignment Group (NAM) group of countries.

Similarly, at the regional level, the challenges posed by Pakistan’s rapid growth of nuclear arsenal, its acquisition of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs), development of new medium-range ballistic missiles and its sponsorship of terrorist attacks in major Indian cities have forced the Indian policymakers to recalibrate their diplomatic engagement with Islamabad. The sub-conventional threat posed by Pakistan’s proxy war has called for India to craft a coherent military-strategic response that will stabilise the regional deterrence scenario in perpetuity.

Pakistan’s acquisition of TNWs has led growing number of Indian analysts to suggest a review of India’s nuclear doctrine and to abandon its NFU policy. Although the current Indian government has rightly resisted from paying heed to such proposals and upheld the doctrine, there is clearly a strong case for Indian policy planners to assess new strategic realities and review the nuclear doctrine in the 20th year of Pokhran II tests. The persistence of sub-conventional threat for more than a decade has necessitated that India not only reinforces the integrity of its doctrinal planning but also signal the enemy about its strong political resolve to carry out the threat should deterrence fails. Not only will it uphold the credibility of India’s nuclear doctrine but also serve a fitting tribute to Pokhran II nuclear tests.

References

1. Statement to Parliament by Prime Minister Vajpayee, 27 May, 1998, URL: http://www.acronym.org.uk/old/archive/spind.htm

2. John F. Burns (1998), “India Sets 3 Nuclear Blasts, Defying A Worldwide Ban; Tests Bring A Sharp Outcry”, New York Times, May 12, 1998, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/12/world/india-sets-3-nuclear-blasts-defying-a-worldwide-ban-tests-bring-a-sharp-outcry.html.

3. “State Department (2005), “U.S.-India Civilian Nuclear Cooperation”, Office of the Spokesman, Washington, DC, July 22, 2005, URL: https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2005/49969.htm.

4. Keynote Address by Foreign Secretary Shri Ranjan Mathai at the Ministry of External Affairs – Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) National Export Control Seminar, URL: https://idsa.in/keyspeeches/AddressbyForeignSecretaryShriRanjanMathai.

5. Press Release: “Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews Progress in Operationalising India’s Nuclear Doctrine”, Prime Minister's Office, January 04, 2003, URL: http://mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/20131/The+Cabinet+Committee+on+Security+Reviews+perationalization+of+Indias+Nuclear+Doctrine.

6. Statement by Shri Jaswant Singh to Parliament on the NPT Review Conference”, May 9, 2000, URL: http://www.acronym.org.uk/old/archive/46india.htm; and Statement by the Prime Minister of India Dr. Manmohan Singh at the Nuclear Security Summit, April 13, 2010, URL: http://www.mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?561/Statement+by+the+Prime+Minister+of+India+Dr+Manmohan+Singh+at+the+Nuclear+Security+Summit.

7. Lahore Declaration, Memorandum of Understanding, February 21, 1999, URL: http://mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?18997/Lahore+Declaration+February+1999.

8. Atul Aneja (2017), “India’s NSG entry more complicated now: China”, The Hindu, June 05, 2017, URL: http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/indias-nsg-entry-more-complicated-now-china/article18723451.ece.

(The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct).

Image Source: https://images.assettype.com/thequint/2018-05/39dcad41-a663-45f8-8963-1081ba902a5f/Hero_01.jpg

Post new comment