It has been reported in the media that China and the ten ASEAN countries have agreed on a single draft of a negotiating text for a Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea (SCS). The formal announcement may be made soon. Negotiations on COC will happen in the next few weeks and months. Thus it would appear that China has been successful in controlling the fall out of the verdict of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in 2016 by working on the contradictions within the ASEAN and also showing the ASEAN that they have little alternative but to accept China’s position and manage their relationships with China.

Background

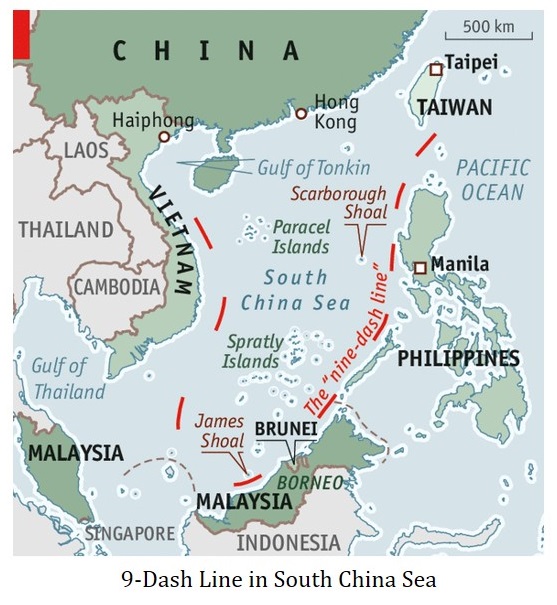

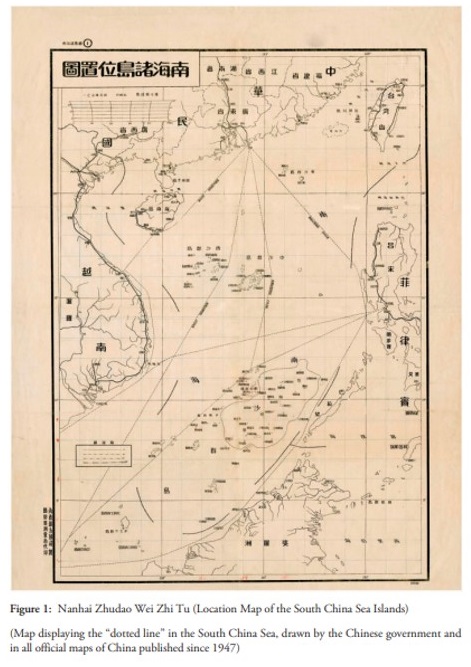

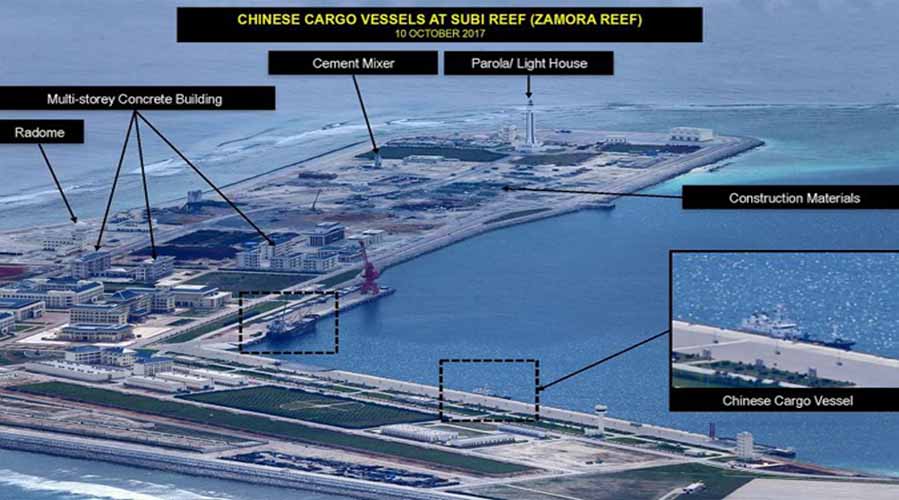

Islands in the SCS have been an area of contention between China and its neighbours for decades. China claims sovereignty over these islands on the basis of the so-called ‘9-dash line’ shown in old Chinese maps, and cites that as its ‘historic rights’. The dispute has led to armed clashes between China and some of its neighbours in the past. China occupied the Mischief Reef in 1995, and many other islands since then. China regards its claim over the islands as non-negotiable. It has constructed civilian and military infrastructure in complete disregard of the international opinion. China is militarily and economically powerful. There is little that the international community can do to change the fait accompli.

The SCS, rich in hydrocarbons and fishery resources, is a major shipping lane for global trade and commerce in the Indo-Pacific region. China’s claims have the potential of curtailing the freedom of navigation through the SCS. The dispute has also created tensions between the US and China. The US has from time to time, sent warships through the region, close to the islands reclaimed by China, to signal that it would protect the freedom of navigation. Ships of other navies passing the SCS, including that of India, have also been occasionally challenged by the Chinese. The dispute over the SCS has the potential of becoming an international flash point.

In November 2002, China and ASEAN, after several years of negotiations, had agreed on a ‘Declaration on Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea’, or DOC. The DOC was essentially an agreement on confidence building measures and practical maritime cooperation. It identified five areas: marine environmental protection; marine scientific research; safety of navigation and communication at sea; search and rescue operations; and, combating transnational crime, including but not limited to trafficking in illicit drugs, piracy and armed robbery at sea, and illegal traffic in arms.

The DOC was a non-binding document that set the stage for an eventual conclusion of a formal and binding COC. Several rounds of discussions have been held since then to arrive at a COC. Not much progress was made all these years. However, the situation may be changing now.

While some - as the Chinese do - may argue that DOC had led to stability in the region, others hold that DOC has been violated with impunity by some countries. Otherwise, how does one explain Chinese occupation of the disputed islands as well as vigorous civil and military construction activity on them? In fact, DOC may have given the Chinese a fig leaf for their occupation of the islands.

The Philippines took the dispute to the PCA for arbitration in 2013. China did not participate in arbitration proceedings. The PCA gave its verdict in 2016 in which it rejected China’s claim of “historic rights” in the SCS as per the “nine-dash line”. The PCA made it clear that its ruling was neither about addressing the sovereignty issues nor about delimiting the maritime boundaries. It was about ascertaining, inter alia, the validity of the ‘historic rights’ argument in the light of the UNCLOS convention. Further, the tribunal also held that as per Article 9 of the UNCLOS, non-participation of China in the proceedings of the tribunal did not constrain the arbitration in any way. 1

The Court rejected the Chinese argument of historic rights. Its judgment merits a detailed quotation. It said,

“Historic Rights and the ‘Nine-Dash Line’: The Tribunal found that it has jurisdiction to consider the Parties’ dispute concerning historic rights and the source of maritime entitlements in the South China Sea. On the merits, the Tribunal concluded that the Convention comprehensively allocates rights to maritime areas and that protections for pre-existing rights to resources were considered, but not adopted in the Convention. Accordingly, the Tribunal concluded that, to the extent China had historic rights to resources in the waters of the South China Sea, such rights were extinguished to the extent they were incompatible with the exclusive economic zones provided for in the Convention. The Tribunal also noted that, although 2 Chinese navigators and fishermen, as well as those of other States, had historically made use of the islands in the South China Sea, there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources. The Tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’.”2

Thus the main argument of the tribunal was that pre-existing rights are not recognised by the convention and that there was no evidence that Chinese controlled these areas historically.

China rejected the ruling outright on the grounds that the PCA was illegal; it had no jurisdiction over the dispute; China had sovereign and historical rights over the islands and the surrounding waters; China has been working with the ASEAN to negotiate a COC as per international law and UNCLOS, and that there was no ground for third-party interference in a dispute of regional nature. Since then China has swiftly moved to undertake constructions on the islands and also installed military equipment. No ASEAN country is in a position to challenge the Chinese militarily in the SCS. Even the US, which has security alliances with many countries in the region, has not been able to prevent China from militarising the occupied islands.

Although the arbitration award was hugely in favour of the Philippines, it was the first to make an about-turn in 2016 when President Duterte came to power. Cambodia and Laos have already been the supporters of the Chinese position while others’ objections have been muted. On the diplomatic front, China has sought to discuss SCS issue with ASEAN and individual countries.

In the meanwhile, China and ASEAN have sought to work out a COC within the framework of the 2002 DOC. But hey have not succeeded in reaching an agreement until now.

The ASEAN has been helpless spectators in seeing China occupy and reclaim the disputed islands. In order to legitimise its occupation, China has made fresh approaches to the ASEAN. Working on the internal contradictions within the ASEAN and taking advantage of the growing inter-dependence of the ASEAN and China in trade and investment, China made fresh overtures to ASEAN. In 2017, the two sides agreed on a new vision and blueprint for China-ASEAN relations up to 2030. Several new areas of cooperation like innovation and tourism have been identified.

In 2017, China conveyed its position on the COC. The Chinese foreign minister, in a press conference, revealed that the parties had agreed on a framework for negotiating the COC. “We also discussed the South China Sea issue. All parties gave full recognition to the current positive momentum of the South China Sea situation. All parties were quite satisfied with the framework of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC) and believed that it lays a solid foundation for substantial consultation of future COC.” He rejected any outside interference in the resolution of the regional dispute.

In April 2018, the ASEAN held its 32nd Summit under the chairmanship of Singapore. Clearly, there was a lack of consensus within the ASEAN on how to handle this difficult issue. The Chairman’s statement merely “took note of the concerns expressed by some Leaders on the land reclamations and activities in the area, which have eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions”, but “warmly welcomed the improving cooperation between ASEAN and China”. The ASEAN leaders were “encouraged by the official commencement of the substantive negotiations towards the early conclusion of an effective Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC) on a mutually-agreed timeline.”

Conclusion

So, that is where the matters stand today. The official negotiations on much-awaited COC may begin soon. How long will it take to arrive at one is anybody’s guess. In the meanwhile, China holds the upper hand as it is already in possession of the islands. What the COC will do is to formalise and legitimise Chinese possession and offer some benefits of cooperation to ASEAN countries. It will also signal that outside powers have no locus standii in the regional dispute.

Refrences

- https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf

- https://www.pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/1801

Image Source: https://www.straitstimes.com/sites/default/files/styles/article_pictrure_780x520_/public/articles/2018/02/06/dw-china-philippines-scs-180206.jpg?itok=bhER9YAB

Post new comment