The keynote address of Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered at the Shangri-La Dialogue on June 01, 2018, succinctly spelt out India’s Indo-Pacific strategy between the “shifting plates of global politics and the fault lines of history”. Over the years, India-US relations have emerged as a mainstay for an “open, stable, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific”. India’s relationship with Russia has been equally important and affirms the need for a multi-polar world-order. Further, the Wuhan Summit of April 2018 has endorsed the value of Indo-China relations for global stability and peace. On one hand, the navies have been playing a significant role for deterring strategic challenges, rendering humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) and tackling non-traditional security (NTS). Concurrently, deft diplomacy has sought to assuage the insecurities of rising tensions, assertions of power, competitions for global commons and asymmetries in trade balance.

Simple evaluation of the above challenges reveals that most situations have their roots in inter-state or intra-state contestations. In other words, the leitmotif of political, economic, technological and strategic interactions have been premised on management of social relations between States, characterised by trade, cyber, power projection, internal dislocation, infrastructure creation, Illegal Unreported Unregulated (IUU) Fishing, piracy and trafficking, to name a few. Ironically, inter-state cooperation on upwelling challenges due to non-social interactions such as relationship between humans and the nature (oceans) have invariably been given a short shrift. Lately, there have been some prompt responses to natural calamities, but these can be construed as episodic. Ocean acidification, eutrophication, over fishing and plastic pollution have assumed leviathan proportions, but has attracted the least collaboration between States. As a result, today ocean health is under threat and so is the Man’s food security. The positive aspect of these challenges is that they offer immense potential for cooperation between India and China, being the two big powers of Asia.

The United Nations (UN) has been making earnest efforts to balance human needs and environmental sustainability since the days of United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) post the Stockholm Conference of 1972. This was followed by Brundtland Commission and the Earth Summit – the United Nations Commission on Economy and Development (UNCED) 1992. Then came the Rio+20 United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (UNSCD), 2012, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), 2014, and finally, the extant Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), 2016. The Paris accord held in December 2015 has been another initiative in this direction. Even though these initiatives have been pan-global and UN-led, ocean degradation has gone out of control. Pollution has proliferated in multitude ways and assumed exponential proportions, primarily due to the lack of regional enterprises. Some of the damages to the environment are already irreversible and many are heading for certain catastrophe, with consequences on the very survival of mankind and sustenance of earth’s natural habitat. Yet the loci of State’s effort remains centered on social issues, while the oceans continue to deteriorate. Since the ensemble of international institutions and regulations has proven to be ineffective, there is a need for change of tack before it is too late.

China and India represent nearly 2.5 billion people, which is a third of the world population and together they share 30 percent of the world GDP in Purchase Power Parity (PPP) terms. If their capacities and heft could be coalesced, it offer them great leverage to effect changes on the planet. This paper explores the areas where the two risings powers could cooperate in transforming maritime governance in order to restore what is lost and rejuvenate what is left.

Bilateral collaboration between India and China has to be progressed in a graduated manner in order to build consensus. Initially knowledge centers like think-tanks, universities and research institutes will have to build awareness and share information, best practices, technology, capacities, etcetera. This knowledge base will then have to be translated into convergence of interests. Convergence will also have to be found with regional forums like the ASEAN, EAS, BIMSTEC, SAARC, Djibouti Code and IORA. This will be a tedious process and will initially be faced with apprehensions from individual States. Once common minimum interests of stakeholders have been identified, the process of norm building and formulation of domestic laws can be commenced. Being the prominent members of the Asian fraternity, India and China will have to take the lead. Cooperation between India and China on ocean governance will not only spur others States in the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific, but can also stimulate a domino effect in other parts of the globe. While all aspects of ‘Blue Economy’ need attention, the areas that have immediate impact on food security are ocean acidification, eutrophication, sustainable fishing and plastic management.

Ocean Acidification - Three major green-house gases (GHG) are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Out of 35.75 Giga tons of CO2 produced worldwide in 2016, India and China together account for 13 Giga tons (35percent)1. When this CO2 is absorbed by the seawater, it increases the acidity of the sea and reduces the calcium-carbonate concentration. This chemical process is called ocean acidification (OA). Since the industrial revolution, ocean acidity has increased by 30 percent and by the end of this century it is slated to increase by 50 percent. Reduced calcium-carbonate saturation also affects calcifying species like clams, coral, oysters and urchins, which serve as food source for billions across the world. Increased OA is believed to be responsible for the recent failure the in oyster industry of $100 million2. While direct contributors to carbon emissions is the transportation industry, other major indirect sources are food, textile and cement. CO2 emissions have directly impacted ocean acidification. Since the exit of the US from Paris accord, the global leadership of GHG emissions lies on the shoulders of India and China. Together they can engender better compliance to the Conference of the Parties’ (COP) 21 goals.

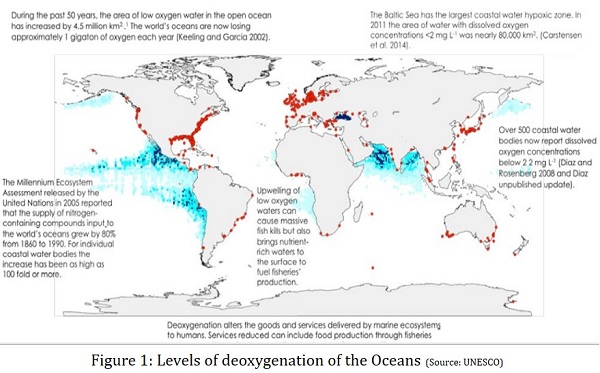

Pollution and Eutrophication - Pollution from sewage, fertilisers, industries and agricultural fields make their way to the oceans through rivers and coastlines. As a result, nitrates and phosphates are discharged into the sea as pollutants. While small quantity of these nutrients is good for aquatic plants, excessive quantities cause eutrophication resulting in explosive growth of algae. Such algae bloom depletes oxygen, restricts light penetration and raise toxin levels in water that are harmful for marine life. Eutrophication often devastates animals, plants, marine economy and tourism3. It has led to vast oxygen dead (hypoxic) zones at sea causing marine life to suffocate and die. This can be induced by natural phenomenon, but is mostly caused due to human induced pollution. The level of deoxygenation of world oceans is illustrated at Figure 1 below4.

It can be inferred from the Figure 1 that oxygen dead/starved zones have become a global phenomenon. Since oceans are being shared by rivers and coasts of multiple countries, its rejuvenation will require a regional approach. Rivers originating in China flow into both Indian Ocean and the Pacific. Besides, some countries in the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific share coasts with both the oceans. Thus, China and India need to collaborate for formulating effective norms for the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific on pollution control and eutrophication.

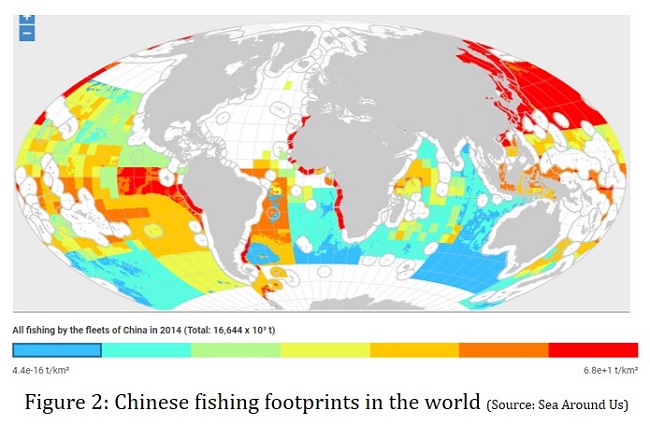

Sustainable Fishing - About three billion people rely on fish for animal protein. Nearly 40 percent of the fish is extracted from coastal regions. There are approximately 18.9 million fish farmers in the world, of which 90 percent are small-scale farmers from developing countries. It is estimated that nearly a third of commercial fishes has already lost5. Advancements in technology and demand of seafood has led to this depletion. Continued fishing at the current rate could have catastrophic impact on fisheries. Thus there is urgent need to adopt sustainable fishing practices. There are 17 Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) that share economic interests in common waters. Evidences suggest that such regulations have been successful in limiting by-catches. North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC) is one such successful RFMO. There is also a requirement to institute fishing regulations for the high seas, such as the prohibition of fishing blue fin Tuna with purse seining and long-lining6. China and India are the two largest producers of fish. Other major producers in the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific are Taiwan, Indonesia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar and Japan7. Figure 2 illustrates footprints of Chinese fisheries in the world8. In order to arrest rapid depletion of fisheries, there is a need to institute RFMOs for the high seas in the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific.

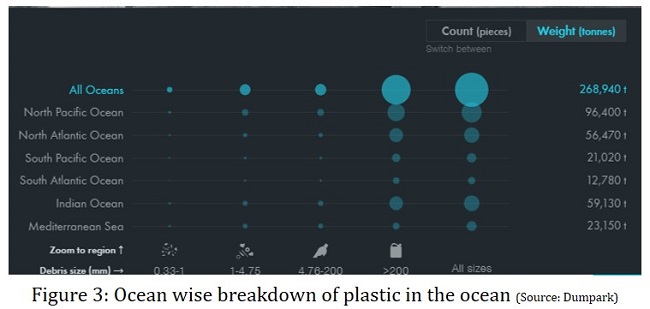

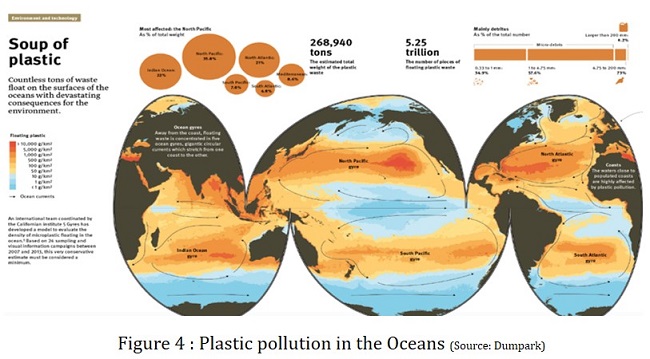

Plastic can be found almost in every corner of the ocean today. It is entangling marine animals and birds, and are being ingested by many. Thus the ocean is slowly turning into a plastic soup9. It is estimated that a total weight of 268,940 tons of plastic bottles, bags and microbeads amounting to 5250 billion pieces are floating in the ocean. Research has shown that as much as 60 per cent of the world's plastic waste comes from just five countries - China, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand. This is likely the reason for North Pacific and Indian Ocean being so heavily polluted.10 The ocean wise breakdown of plastic pollution is as follows:

It can be seen from the illustration at Figure 411 that the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific is almost completely choked with plastic. Also, the currents through the Malacca strait carry plastics between the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal. This has serious implications on survival of the marine species and food security. This needs a regional approach and can be an agenda for China-India cooperation for regional maritime governance.

Over exploitation of the oceans by man has reached catastrophic proportions. Increased ocean acidity and reduced calcium-carbonate is affecting the very sustenance of calcifying species like clams, coral, oysters and urchins, with serious implications on food security. In addition, vast oxygen dead (hypoxic) zones due to dumping of land based pollutants at sea are causing marine life to suffocate and die. Advancements in technology and increased demand of seafood has led to depletion to fisheries at sea. This has been further aggravated by the spread of plastic in most parts of the ocean. Years of UN led environmental initiatives have yielded little towards oceanic health. Thus, inter-state and regional cooperation appears to be the only option to restore what is lost and rejuvenate what is left.

Mechanism - India and China being the two emerging powers of Asia with substantial capacities and influence in the Indian Ocean and Asia Pacific, may not have the wherewithal to restore ocean health all by themselves. Nevertheless, they are the last hope in Asia. Bilateral collaboration between India and China has immense potential, but has to be progressed in a graduated manner in order to build consensus. The proposed mechanism is as follows:-

Cooperation between India and China on ocean governance will not only spur others States in the Indian Ocean and Asia-Pacific to keep the Oceans safe from environmental deterioration, but can also stimulate a domino effect in other parts of the globe. This will also advance Prime Minister Modi’s vision of building an inclusive Indo-Pacific.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Links:

[1] https://www.vifindia.org/2018/september/05/prospects-for-india-china-maritime-cooperation

[2] https://www.vifindia.org/author/somen-banerjee

[3] http://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/overview.php?v=CO2andGHG1970-2016&sort=des8

[4] https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/co2/story/What+is+Ocean+Acidificationpercent3F

[5] https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/estuaries/media/supp_estuar09b_eutro.html

[6] http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002651/265196e.pdf

[7] http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/oceans/solutions/sustainable_fisheries/

[8] https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/sustainable-fishing/

[9] https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/leading-countries-in-fishing-and-aquaculture-output.html

[10] http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/spatial-catch

[11] https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/what-we-do/oceans/plastics/

[12] https://app.dumpark.com/seas-of-plastic-2/#

[13] http://dumpark.com/projects/soup-of-plastic-infographic/

[14] https://www.advancedwaterinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Plastic-Pollution.jpg

[15] http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?title=Prospects for India–China Maritime Cooperation&desc=&images=https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/Plastic-Pollution.jpg&u=https://www.vifindia.org/2018/september/05/prospects-for-india-china-maritime-cooperation

[16] http://twitter.com/share?text=Prospects for India–China Maritime Cooperation&url=https://www.vifindia.org/2018/september/05/prospects-for-india-china-maritime-cooperation&via=Azure Power

[17] whatsapp://send?text=https://www.vifindia.org/2018/september/05/prospects-for-india-china-maritime-cooperation

[18] https://telegram.me/share/url?text=Prospects for India–China Maritime Cooperation&url=https://www.vifindia.org/2018/september/05/prospects-for-india-china-maritime-cooperation