Zorawar Singh was a prominent military commander and statesman in the army of Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu and Kashmir. He played a pivotal role in defining the modern political boundaries of the Union Territories of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir. Zorawar Singh led the military campaigns that helped in the process of assimilation of Ladakh and Gilgit-Baltistan into the erstwhile Dogra state in Jammu and Kashmir. He was also able to temporarily control a significant part of western Tibet up to the holy Lake Manasarovar until he was killed in battle and the Dogra forces had to retreat. Despite his military successes, General Zorawar’s contributions to Indian military history are largely forgotten.

Zorawar Singh was a Rajput Dogra born in Ghaloor, Kangra (in present-day Himachal Pradesh), in 1786. He had a very humble beginning. He couldn’t receive any formal education as he had to flee from his village due to a property feud within his family. He joined Raja Jaswant Singh’s household in Galian, Jammu, where he learned to use military weapons and horseback riding. Later, he joined the Riasi garrison as a sepoy in Maharaja Gulab Singh’s army. [1]

Maharaja Gulab Singh promoted Zorawar Singh to the position of Supplies Inspector for the forts in northern Jammu after he displayed his skills in implementing an effective and profitable rationing system for food resources amongst the troops. [2] His relationship with Gulab Singh deepened as he became one of the ruler’s confidants. Zorawar Singh was appointed Wazir of Kishtwar by Gulab Singh in 1823, which helped him gain experience in civil administration. Zorawar Singh used this period in Kishtwar to prepare his army for the upcoming campaigns that he would lead in Ladakh and Tibet.

In order to understand the reasons for Zorawar Singh’s military campaign and the corresponding assimilation of Ladakh into Jammu and Kashmir, one has to understand the cultural, political and economic importance of the region. Ladakh’s earliest links with Indian cultural ethos took place with the spread of Buddhism in the region. The essence of Buddhism in Ladakh can be found in the stupa engravings, stray sculptures, colossal images and rock carvings at different sites along the trade routes in the river valleys, such as Choglamsar, Mulbek, Shey and Suru etc. [3] The rock sculptures dotting the landscape bear witness to the early introduction of Buddhist art in Ladakh from the Indian side, especially from Kashmir, before the Tibetan influence began in the region. The famous Maitreya rock reliefs at Mulbek, Tumail and Kartse depict the close affinity with Kashmiri art, which in turn was influenced by Gandhara art. [4]

Apart from the cultural connections that Ladakh shared with India, Ladakh played a pivotal role in overland trade and communication. [5] It was strategically located at the junction of the lucrative trade routes to Xinjiang, Central Asia and Tibet. Despite the high mountain ranges and inhospitable passes, caravan traders from India and Central Asia exchanged items such as carpets, wool, shawls, silk and cotton fabric, precious stones and saffron etc. The most important commodity passing through Ladakh was the fine under-wool of sheep and goats from Western Tibet, used to manufacture Kashmiri shawls. [6] This trade was almost exclusively monopolised by the Kashmir weavers and to an extent, the Kashmiri economy depended on it. This economic importance of Ladakh coincided with the political fragility of the Namgyal dynasty of Ladakh. The territorial integrity of Ladakh was under constant threat from the Balti rulers of the north. [7] Therefore, the desire to control the Pashmina trade was one of the primary reasons for the military campaign of the Dogras in Ladakh in 1834. [8]

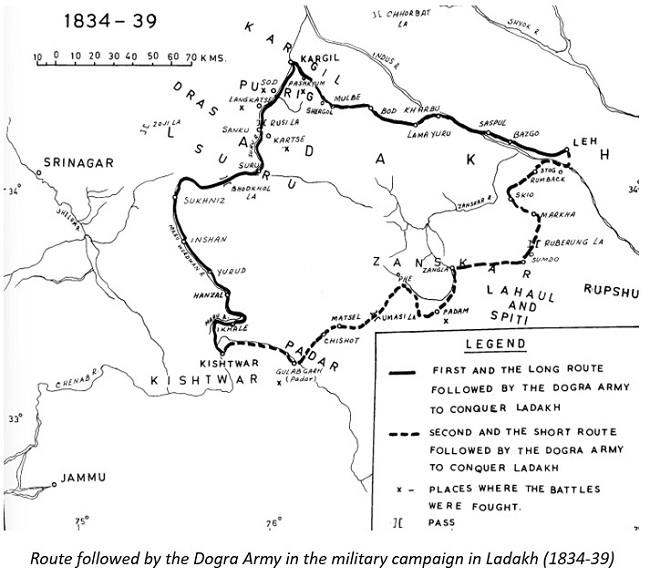

The military campaign in Ladakh was conducted at heights above 12,000 feet above sea level. [9] At those heights, the temperatures dropped to sub-zero levels, even at the peak of summer. Along with that, the forces also had to acclimatize to the natural environment, where even breathing is laborious. Apart from the climatic conditions, roads in Ladakh in the 19th century were no better than bridle tracks. Goods were transported by pack animals like horses, mules and yaks. [10] In the high-altitude snowy passes, the yak was the most useful beast of burden. The Dogra army under General Zorawar Singh was well prepared and had intensive training in snow and high-altitude warfare. They had also built an effective logistics network between Kashmir and Ladakh. The campaign was launched in July 1834 with 10,000 Dogras, comprising elements from the artillery, infantry and cavalry. [11] The infantry was comprised of soldiers who were trained match- lockers and, at the same time, wielded swords and spears. [12]

Zorawar Singh took the route through Kishtwar and entered the Suru Valley. [13] The first encounter with the Ladakhi forces took place on August 16, 1834, at Sankoo along the Suru River in the Suru Valley. The Dogra forces surrounded the Ladakhi hill fortification. After a day of intense fighting, the Dogras managed to dislodge the hardy Ladakhi troops. Zorawar Singh and his forces stayed in Suru for a month and strengthened the fortification. Zorawar Singh ordered his troops not to destroy the crops in the captured territories, as he knew that adequate provisions would be needed to sustain the campaign in the rugged and barren lands of Ladakh. [14] This step provided the much-needed provisions for the army to endure the campaign and also ensured the support of the peasants of Suru Valley, who placed themselves under Dogra protection. [15]

In mid-September 1834, Zorawar Singh marched his army to Pushkyum (Pashkum) along the Wakha River, where the Ladakhis had organised a defensive position. After a long-drawn-out conflict, the Dogra forces broke through the defences at Pushkyum. The siege of the fort at Sod occurred after the Ladakhi forces retreated there. Mehta Basti Ram, an enterprising and brave Colonel in Zorawar's army, assaulted the fort with five hundred soldiers under the cover fire of the artillery and gained possession of the fort, and held many Ladakhi as prisoners. [16]

As the winter approached, Zorawar Singh tried to negotiate with the Ladakhi King Tsepal Namgyal and restore peace. He made an offer to the Ladakhi authorities that if they paid Rs 15,000, then the Dogras would return. [17] But King Tsepal closed all doors leading towards peace by marching with a strong force of 22,000 troops towards Mulbik (Mulbekh) along the Wakha River. The Dogra forces faced heavy setbacks and were pushed back to Langkartse in the Suru Valley. [18] The Ladakhi forces didn’t attack the recuperating Dogra camp at Langkartse when they were trapped there by the cruel winter. Instead, they waited for spring and launched an attack on Langkartse months later, in April 1835. By this time, the Dogra camp had been reinforced and was prepared to resume the hostilities. Zorawar Singh launched a surprise attack at the Ladakhi camp and routed them. This was a major victory in the political assimilation of Ladakh.

After regaining control of Pushkyum and Mulbik, Zorawar Singh marched eastward to Lamayuru and established a Dogra headquarters. The Ladakhi King wanted to restore peace in the region and entered into an agreement with the Dogras. Ladakh agreed to pay a yearly tribute of Rs 20,000 along with a war indemnity of Rs 50,000. [19] The Dogras also stationed Munshi Daya Ram as their representative in Leh. [20] This marked the formal assimilation of Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir under the Dogras. Although Maharaja Gulab Singh was still a subject of the Sikh Empire, he considerably had a free hand in the administration of regions bordering Kashmir and Ladakh. The Sikh Empire was preoccupied with local matters in Lahore, especially because of the political turmoil that erupted after the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839.

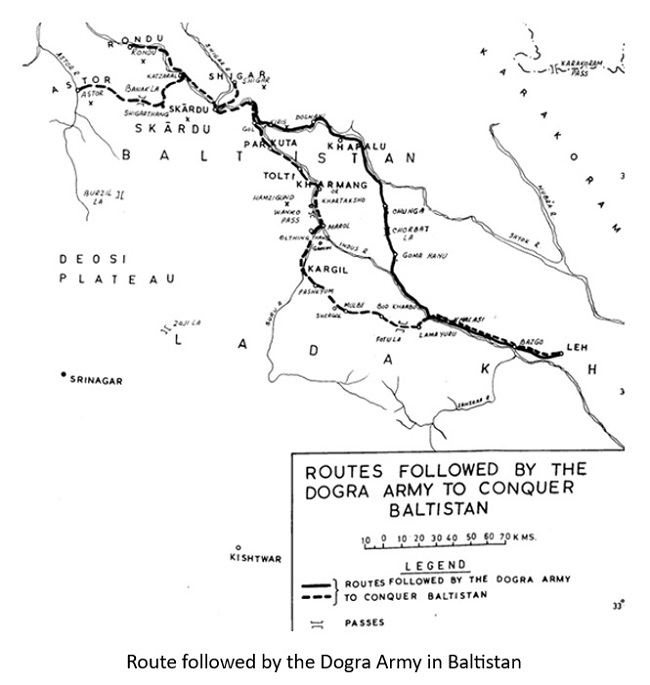

Zorawar Singh had to deal with multiple revolts in different parts of Ladakh in the following years, which kept him preoccupied. [21] After the consolidation of power in Ladakh in 1839, Zorawar Singh started preparing the grounds for the conquest of Baltistan into Jammu and Kashmir. Baltistan was divided into three states: Skardu, Gilgit and Hunza, which in present-day Pakistan Occupied Gilgit-Baltistan.

Zorawar Singh used the internal conflict between Ladakh and Skardu to his own benefit in the expedition against Skardu at the end of 1840. A force of 15,000 Dogra soldiers was raised by Zorawar Singh, which was further reinforced by Ladakhi soldiers. [22] The Ladakhi also provided him with hill ponies that helped him maintain the long lines of communication. Zorawar Singh consolidated the position of Jammu and Kashmir state over Kargil, Dras and Suru on his way towards Skardu.

The Dogra forces under Zorawar Singh crossed the Indus at the peak of winter in early 1841 and defeated the Skardu forces, forming the defensive line with the skilful use of cavalry and infantry tactics. Ahmad Shah, the ruler of Skardu, retreated to the Skardu Fort, which was situated on the edge of a high plateau. The fort was surrounded by the Indus River on three sides, and the passage leading to the main citadel was steep and extremely difficult to climb. Thus, because of the difficulty of accessing the fort and the availability of sufficient provisions, it was believed that the fort was impregnable. The fort in Skardu was laid under siege by the Dogras, and the water supply to the fort was cut off. The Skardu forces under the ruler Ahmed Shah were forced to surrender and accept a tributary status to Jammu and Kashmir. Zorawar Singh took control of Kharmang, Khapalu, Tolti, Parkuta, Shigar, Rondu and Astor in Skardu state. Ahmed Shah was deposed, and his son, Mohammad Shah, was made the new ruler of Skardu and was ordered to pay an annual tribute of Rs 7,000 to the Dogras. [23] Other petty rulers of Kharmang, Khapalu, Tolti, Parkuta, Shigar and Rondu were ordered to pay similar tributes. [24] The other two states, Gilgit and Hunza, accepted the suzerainty of Gulab Singh without any retaliation.

By the end of 1841, Gilgit-Baltistan and Ladakh came under the control of Raja Gulab Singh. The suzerainty of the Dogras over these kingdoms ended the centuries-old practice of plundering expeditions that the Baltis and the Ladakhis conducted against each other. Thus, it brought relief to the people of both kingdoms, especially those living in Purig, Khapalu and Kharmang, who were under constant attack. Alexander Cunningham, who visited Ladakh during 1846-48, pointed out that the Dogras constructed bridges, roads and bridle-tracks in the region. [25] This greatly benefited the inhabitants of the area, since their principal means of livelihood were derived from the transport of merchandise.

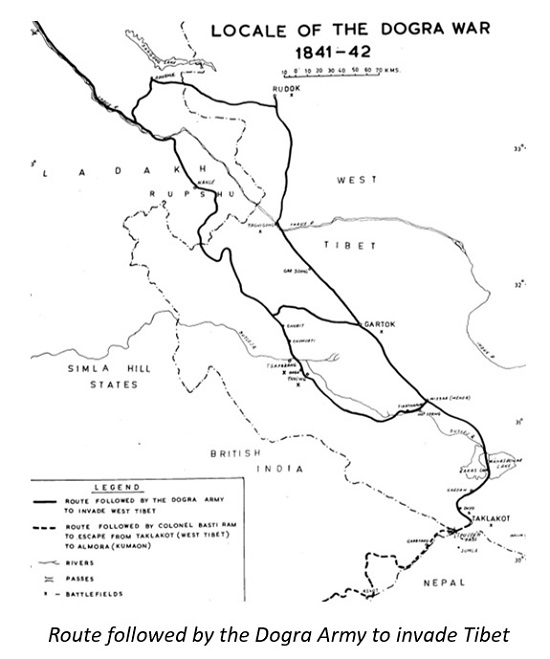

In the meantime, during the 1830s, Western Tibet, specifically the regions of Rutog and Gar, had become economically vital to Jammu and Kashmir because of the high-quality wool produced in the region. Tibet was aware of the growing demand for pashm (wool) and wanted a larger share of the profits. Thus, they tried to strengthen the direct trade route with the British-controlled territory of Rampur in Himachal Pradesh, thus bypassing Ladakh and denting the importance of Jammu and Kashmir. [26] Zorawar Singh was aware of these undesirable developments, and in early 1841, he wrote to the Garpon (local Tibetan leader) of Gartok, forbidding him from supplying pashm to any other region except Ladakh. Based on Ladakh’s old territorial claim over West Tibet, [27] Zorawar Singh also demanded a tribute from Rutog and Gar, which were formerly part of Ladakh until the mid-17th century. [28] But neither the direct trade by Tibet with the British dwindled nor the tributary status were accepted by Rutog and Gar. Thus, with Ladakh in their hands, Gulab Singh and Zorawar Singh directed their efforts towards stopping direct trade between Tibet and British India and launched the military campaign against Tibet. [29]

Zorawar Singh’s campaign against Tibet started in May 1841 with an army of 6,000 soldiers, which included Dogra, Ladakhi and Balti soldiers. [30] Zorawar Singh followed the route south of Pangong Tso and entered Tibet. Rutog was captured on June 5, 1841, with little resistance. After this, Gar was captured within the first few weeks of the military campaign. Zorawar Singh led his army up to the source of the river Indus in Mansarovar Lake. The Dogras marched towards Taklakot, bordering Nepal, in order to conquer the entire territory to the west of Mayum Pass. The Tibetan authorities hastily dispatched General Pishi with a small force to check the sudden and quick thrust of the Dogras. After some feeble resistance, on September 6, 1841, the Dogras took possession of Taklakot.

Zorawar Singh consolidated his position in western Tibet by constructing fortresses at such strategic places as Rutog, Gar, Tsaparang, Daba, Churit, Chumurty, Kardam, Tirtha Puri and Taklakot. [31] All these forts were also garrisoned with Dogra soldiers. The Tibetan local functionaries were taken into service and asked to pacify the populace. Zorawar Singh also adopted measures to ensure the supply of shawl-wool to Ladakh. The Dogra occupation of West Tibet impacted the direct trade between Tibet and British-protected territories in India.

The Tibetans deliberately avoided a major encounter with the forces of Zorawar Singh in western Tibet and lured him deeper into Tibet. They were aware of the fact that the fast-approaching winter was also going to aid the Tibetans. Zorawar Singh was able to capture and consolidate the Tibetan territory up to Taklakot until the autumn of 1841. However, illness (mainly pneumonia) and frostbite started taking a heavy toll on the Dogra army. To cope with the winter, the Dogra troops had to burn the hardwood from the rifles’ butt-stocks. Their military supplies and food were also running short. The cavalry, in fact, had virtually ceased to exist.

The Tibetans sent a large army to recapture the lost territories from the Dogras at the start of winter in November 1841. There were two smaller encounters between the two forces in which the Tibetans annihilated the Dogra detachments. The Dogra army suffered a crushing defeat on December 12, 1841. [32] General Zorawar Singh was hit in the shoulder during the fight, yet he didn't stop fighting. In the end, he was outnumbered, and a Tibetan lance went through his torso. The Dogra forces became demoralized after the death of Zorawar Singh. Many were captured by Tibetan forces, and many of them perished in their hastily organised flight from Tibet due to the bitter cold. The Tibetans were able to quickly retake Rutog and Gar from the retreating Dogra forces.

The Tibetans then invaded Ladakh. The Tibetan advance was halted after the arrival of Dogra reinforcements. The Tibetans and Dogras signed a peace treaty in Leh on September 17, 1842. Under the terms of the treaty, the Tibetans accepted the Dogras as the legitimate authority in Ladakh and the old established frontiers were reaffirmed. [33] This established the boundary between Gulab Singh’s Ladakh and Tibet. In 1846, after the defeat of the Sikh Empire in the first Anglo-Sikh war, the British recognized Gulab Singh as the independent sovereign of the northern territories of Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh and Baltistan-Gilgit under the British paramountcy. [34]

Zorawar Singh's military campaigns in Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet were not only marked by strategic brilliance but also by his diplomatic acumen. He successfully negotiated with the local rulers, earning their loyalty and support for the Dogras. His ability to forge alliances and maintain stability in the regions he brought under Dogra control contributed significantly to the expansion of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir. Apart from his military achievements, Zorawar Singh was known for his administrative skills. As the governor of Ladakh and other regions, he implemented policies aimed at promoting economic growth and ensuring the welfare of the local populace. His governance style reflected a balance between firmness and fairness, earning him the respect of both his subjects and contemporaries. Despite facing challenges, his diplomatic prowess left an indelible mark on the history of Jammu and Kashmir.

[1]Major-General Palit, D. K., (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 37

[2]Major-General Palit, D. K., (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 37

[3]Francke, A. H., Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi, page 80

[4]Saplazin, Sonam, ‘Analytical Study of Sculptures of Ladakh with Preliminary Account on Kashmir Sculptures.

[5]Warikoo, Kulbhushan, The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, New Delhi, 2023, page 16

[6]G.J. Alder, British India’s Northern Frontier 1865-1895: A Study in Imperial Policy, Longman, London, 1963, page 15

[7]Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, pages 28-29

[8]Dolma, Rinchen, The Early Years of the Dogra Conquest of Ladakh (1834-1846), page 438

[9]Major-General Palit, D. K., (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 38

[10]Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 27

[11] Major-General Palit, D. K., (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 38

[12]Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 30

[13] Cunningham, A., (1997), Ladakh, Physical, Statistical, and Historical, Srinagar, page 331

[14]Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 31

[15]Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 31

[16]Cunningham, A., (1997), Ladakh, Physical, Statistical, and Historical, Srinagar, pages 334-335

[17]Francke, A. H., A History of Western Tibet, 1995, page 142

[18]Major-General Palit, D. K., (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 39

[19] Major-General Palit, D. K. (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 40

[20] Panikkar, K.M., The Founding of Kashmir State (London, 1953), page 78

[21] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, pages 35-36

[22]Major-General Palit, D. K. (1972, April). Jammu and Kashmir Arms. Dehra Dun, page 42

[23] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 55

[24] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 57

[25] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 59

[26] Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2023), The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, page 60

[27] This Tibetan territory, known as Na ris skor gsum, with the districts of Rudok, Gartok, and Taklakot, was conquered by Senge Nam-gyal (Ca. 1600-1645 CE), the powerful Ladakhi ruler. But during the period of his grandson, Deage Nam-gyal (Ca. 1675-1700 CE), it was taken back by the Tibetans.

[28] Foreign. Secret C., National Archives of India, New Delhi, 21 June 1841, No.15

[29] Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2023), The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, page 60

[30] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 68

[31] Datta, C.L., General Zorawar Singh: His life and achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan and Tibet, New Delhi, 1984, page 70

[32] Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2023), The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, page 62

[33] Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2023), The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, page 63, Foreign Secret F., National Archives of India, New Delhi, September 1889, Nos 211-17 (K.W.3)

[34] Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2023), The Crossroads Kashmir, India’s Bridge to Xinjiang, page 63

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Links:

[1] https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/march/22/Looking-Back-at-General-Zorawar-Singh-and-his-Campaigns-An-Assessment

[2] https://www.vifindia.org/author/Saudiptendu-Ray

[3] https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-599670c8edb00e98f42aa7cc037b8eee-lq

[4] http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?title=Looking Back at General Zorawar Singh and his Campaigns: An Assessment&desc=&images=https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/main-qimg-599670c8edb00e98f42aa7cc037b8eee-lq.jpg&u=https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/march/22/Looking-Back-at-General-Zorawar-Singh-and-his-Campaigns-An-Assessment

[5] http://twitter.com/share?text=Looking Back at General Zorawar Singh and his Campaigns: An Assessment&url=https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/march/22/Looking-Back-at-General-Zorawar-Singh-and-his-Campaigns-An-Assessment&via=Azure Power

[6] whatsapp://send?text=https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/march/22/Looking-Back-at-General-Zorawar-Singh-and-his-Campaigns-An-Assessment

[7] https://telegram.me/share/url?text=Looking Back at General Zorawar Singh and his Campaigns: An Assessment&url=https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/march/22/Looking-Back-at-General-Zorawar-Singh-and-his-Campaigns-An-Assessment