The debate on whether the time has come for India to have a Uniform Civil Code that will govern personal laws of all its citizens irrespective of their religious affiliation, has been renewed with the Union Government seeking a report from the Law Commission of India on the subject. Last month, the Union Ministry of Law and Justice asked the Commission to submit its perspective on all aspects of the proposed legislation. It is not something that will be decided in a hurry. An indication of this came when the then Minister for Law and Justice DV Sadananda Gowda said, the Commission could take “six months to a year” in submitting its report. Once the report comes, it will have to be discussed with various stakeholders including political parties. Only after a broad-based consensus is reached, will the possibility of a Uniform Civil Code becoming a reality, turn into certainty. Meanwhile, the Government must not lose focus and should ensure that the matter is brought to its logical conclusion. This will be one of the primary tasks of the new incumbent in the Ministry.

Unfortunately, for various reasons, partly driven by parochial politics and partly influenced by a mindset of not considering the subject to be of priority, every Government in the years since independence sought to brush the issue under the carpet. One of the consequences of the failure to settle the debate has been that vested interests from all sides have had the opportunity to exploit the issue, link it to religion and raise emotional tempers. One of the most quoted arguments is that a common civil code will violate the religious rights of the country’s largest minority community. This apprehension ought to have been long settled by a reading of Article 44 of the Constitution of India, which implicitly argues that the object of a Uniform Civil Code is to integrate India by bringing all communities on the “common platform on matters which are at present governed by diverse personal laws but which do not form the essence of any religion, e.g. divorce, maintenance for divorced wife” (Shorter Constitution of India; Durga Das Basu). Thus, only matters that do not form the “essence” of any religion would be brought under a common civil code’s jurisdiction. In short, Article 44 has already provided a framework that delinks Uniform Civil Code from religion.

However, the Constitution-framers’ desire for the country to adopt a common civil code — “The State shall endure to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India” — has remained unfulfilled because Article 44 finds place in Part IV of the Constitution, which deals with Directive Principles of State Policy. And while the Constitution holds the Directive Principles to be “fundamental” in the effective governance of the country, it also clarifies that they are not enforceable by a court of law and that they need to be implemented through legislation. Additionally, the courts cannot “compel” the Government to make laws for the implementation of the Directives. This is the reason why the courts have had their hands tied when hearing cases relating to personal laws. In the absence of a common civil code, personal laws, such as the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, have held their ground. But they are also being increasingly challenged — at least those provisions that the petitioners consider as violating their fundamental rights.

Spurred by rising grievances, the courts have begun to look into the issue from a different angle: those of violation of rights the Constitution guarantees. Nearly all of these cases have to do with marriage, polygamy, divorce and maintenance — and with Muslim women petitioners seeking redressal. They have all, in different ways, claimed that they have been constitutionally short-changed under the pretext of religion, and by the (mis)use of the Muslim Personal Law. The issue has thus become one of gender justice, where Muslim women feel that Islamic laws are being used to deny them rights that are enshrined in the Constitution. There is still some confusion among women activists on whether they want justice for Muslim women within the framework of the Islamic laws or they believe that, given the propensity of the hardliners and clerics, such justice is possible only through a Uniform Civil Code.

The Supreme Court has already agreed to examine whether the Islamic laws governing marriages and inheritance violate the fundamental rights of Muslim women in this country. Over the years, it has had to grapple with matters of similar kind. In 1995, it decided on the Sarla Mudgal versus Union of India case. While the issue at hand here was that of a second marriage of a Hindu man who had converted to Islam (the court held the marriage void since the man had not dissolved his first marriage under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955), the judge did ask the Government to consider the implementation of Article 44 of the Constitution.

In April this year (2016), Shayara Bano approached the Supreme Court, seeking a ban on triple talaaq and polygamy. She told the court that her in-laws had first begun to trouble her by demanding that her parents give them money and a car. When the torture became unbearable, she returned to her parents’ home, and one day received a divorce letter from her husband. A local cleric held the document to be valid. That’s when she arrived in the court for justice.

A month later, Afreen Rehman knocked at the apex court’s doors with a similar grievance. She had been served divorce papers by her husband through Speed Post after she left her in-laws’ place because she was being mentally tortured to get dowry.

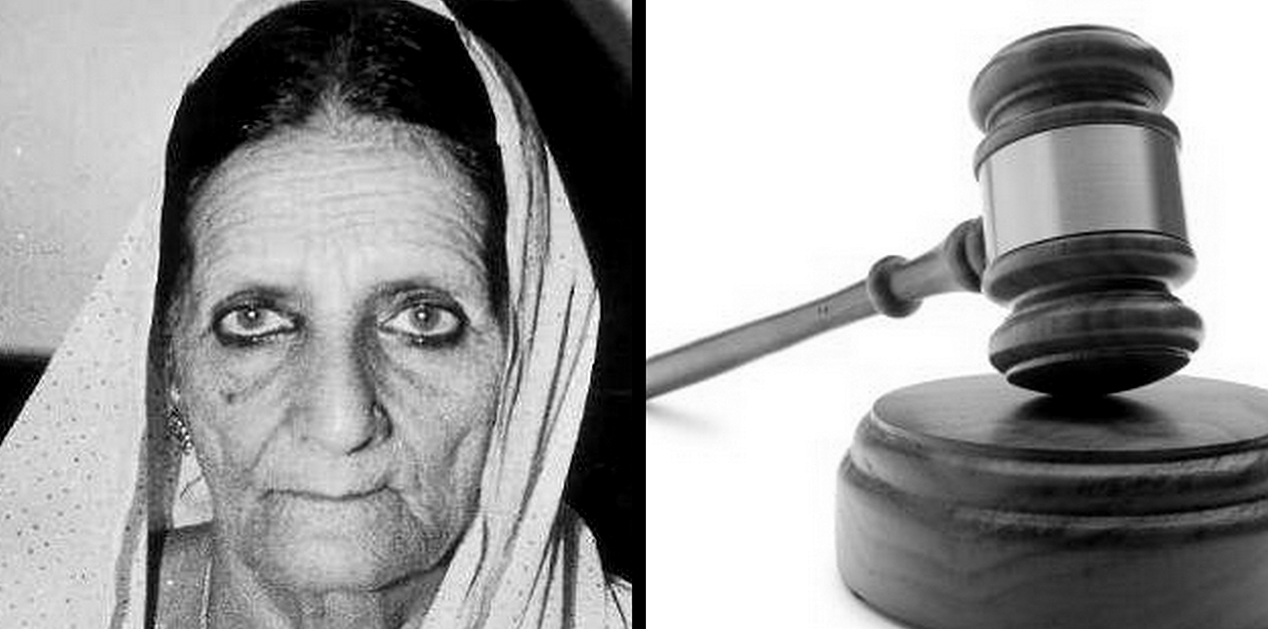

These incidents remind us of the 1985 landmark verdict of the apex court in the Shah Bano case and the aftermath. A divorcee, Shah Bano had gone to the Supreme Court, which granted her alimony. The court had upheld the right of a divorced Muslim woman to post-divorce maintenance under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. This enraged the hardliners in the Muslim community and the various clerics who said the order was against their personal laws. Had the Union Government stood its ground, perhaps the issue of discrimination through Islamic laws would have been addressed 30 years ago. Unfortunately, the Government of that day bowed to Islamic fundamentalists and brought in a legislation — the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, to negate the apex court’s ruling and remove alimony to Muslim women from the secular provisions of the law. The Government may have won over some vote-banks, but it lost an opportunity to set in motion reforms of personal laws to give equal rights to women of a certain community.

Some 17 years later, the apex court intervened once against in what is another landmark case: That of Shamin Ara versus the State of Uttar Pradesh. It invalidated arbitrary divorce and clearly laid down the guidelines as spelt in the Quran for pronouncing talaaq. The ruling was supposed to end the fraudulent practice of sending divorce deeds by post (now even e-mails) and depriving Muslim women from maintenance while their matter was pending before the courts. Justice Krishna Iyer had observed in a ruling (A Yousuf Rawther versus Sowramma), “The view that the Muslim husband enjoys arbitrary, unilateral power to inflict divorce does not accord with Islamic injunctions…” In a more recent case, that of Vishwa Lochan Madan versus Union of India (2014), the Supreme Court held that rulings of Sharia courts and fatwas were not binding on the persons seeking them. The court did not, however ban these activities, thus in a way letting distortions through the supposed use of Islamic law to continue.

It is important to revisit these instances, if only to underline that the lofty pronouncements and clarifications of the court over the years have done little to check the discrimination faced by Muslim women in matters of divorce and maintenance. They continue to battle persecution and prejudice in the name of Islamic law. What is worse is that the Muslim clerics, who know the Sharia and should know that the women who have approached the court (and many more who have suffered similarly but have not gone to the court) have suffered injustice, have aligned themselves on the other side that is opposed to judicial intervention. This can only strengthen the stand of those who believe that a Uniform Civil Code is the solution.

The battle is being fought not just in the courts but also within the Muslim community. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board has strongly opposed judicial intervention in matters of Muslim personal laws, claiming that such actions go against the rights of the minority community to govern itself through the Sharia in civil matters. On the other hand, various Muslim women organisations, including the All India Muslim Women Personal Law Board, which was formed in 2005, are pushing for judicial relief on matters of divorce and polygamy, saying that the Sharia was being misinterpreted by the clerics to sustain their hold over the community. They appear to be reflecting the mood prevalent among many Muslim women across the country. According to a survey conducted by the Mumbai-based Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan in 2013, as many as 92 per cent of the women contacted, demanded a complete ban on what has come to be known as triple talaaq and supposedly sanctioned by the Muslim personal laws.

This fight has also assumed a political dimension. Soon after the Government decided to seek the Law Commission’s opinion on a Uniform Civil Code, senior Congress spokesperson Abhishek Manu Singhvi dubbed the move as “stuntbaazi”. In a comment to The Hindu, he asked, “What steps has the (BJP-led NDA) Government taken before chucking the issue into the political domain?” He did, however, add that, “if genuine efforts are made by the Government, then maybe something can be achieved”.

But politics has been there since the Shah Bano case. More recently, in an interview to The Indian Express, former Supreme Court judge A R Lakshmanan, who had headed the Law Commission which gave the 211th and the 212th reports on registration of marriages and civil marriages respectively, had recommended to the then Congress-led UPA Government that all marriage and divorce matters should be brought under the ambit of a uniform law. “Everything was put in cold storage by the Government. I am disappointed that no effort was made to examine the feasibility of a Uniform Civil Code,” he lamented.

One of the points of exasperation in respect to the Muslim Personal Law has been that it has been in continuance while personal laws governing the Hindu faith have been overhauled. The Hindu Code Bill had led to heated debates in the Constituent Assembly, and by the time it came before the Lok Sabha (1952-57 term), it had been broken down into three specialised Bills, outlawing polygamy and placing daughters on equal footing as widows and sons in matters of inheritance, among other things. There were many ‘Hindu nationalist’ members who saw in these changes an insidious design by Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘secular’ Government to pose a threat to the stability and integrity of traditional aspects of marriage and inheritance within Hindu society. But the larger grievance had to do with the bias — that Muslim personal laws remained untouched while laws governing the Hindu civil life were being reformed. Prominent nationalist leader Syama Prasad Mookerjee declared that the “Government did not dare to touch the Muslim community”. In support of Nehru, it is said that he decided to leave Muslim personal laws alone as a special concession to the minority community which needed special attention to be integrated into Indian society post-independence. His supporters also add that the final Hindu civil laws were less reformist than he wanted, because he conceded to demands made by people like Mookerjee and Rajendra Prasad, among others. They argue that discrimination exists even within Hindu laws of marriage and maintenance despite the reforms. That may be so, but these too could be addressed by a common civil code. Whatever the case may be, the double standard has remained a sore point in the narrative.

(The writer is a senior commentator and public affairs analyst)

Published Date: 19th July 2016, Image Source: http://www.thehindu.com

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Vivekananda International Foundation)

.jpg)

Post new comment