In his seminal work, ‘The War Puzzle’ John Vaquez establishes that territorial issues constitute the fundamental cause of interstate wars in the modern global system since 1495. Elaborating further upon his thesis, Vasquez argues that territorial issues per se do not constitute a direct causal variable in leading to wars. However, the very presence of ‘territoriality’ as a contentious issue makes wars more probable.1 As such, a thorough study of territorial disputes institutes a core dimension within the domain of international and security studies.

With international politics no longer governed along ideological fault lines, territorial equations today are often rooted in geopolitical contexts and are thus regarded as manifestations of perceived national interests (political, economic, and security) of the states. Due to this close association with these national concerns, territorial disputes frequently assume a nationalistic dimension. The sentiment of nationalism acts as a dualistic construct of cause and effect in determining the course of territorial conflicts, and their relative importance in a country’s political and strategic calculus.2

The Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands dispute in the East China Sea is a conflict that entails implications not only for the East-Asian regional dynamics, but has rather become the euphemism for Great Power Politics. This situation owes to the existence of a complex conflict structure involving ‘assertive’ positioning (attitudes and behaviour) by the parties (structures) involved in the dispute3: the People’s Republic of China regards the Islands as their ‘core national interests,’4 and hence is committed to recover the Islands through diplomatic or military means; Japan refutes the very existence of any sovereignty debate over the Islands and bought three of the disputed Islands from their private owners in 2012, thus, further intensifying the conflict; the United States of America, though claiming a neutral stance over the sovereignty debate, is committed to defend the Japanese interests under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the US and Japan.

Though both China and Japan have, by far, refrained from resorting to direct armed confrontation for settling the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute, any military resolution to the issue would render a precursor to the future of the power transition theory between China and the United States of America. This inference is rooted in the psychological underpinnings associated with the outcome of wars, and their effects upon the ‘power equations’ between states. In case of a Sino-US war over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets, a resolution in favour of China would undermine the confidence of the East Asian nations in America to preserve their interests in the region. This situation would destabilize the very existence of US pivot in Asia. Moreover, the military victory would consolidate China’s position as the ‘hegemonic power’ in East Asia. This would further narrow the ‘power gap’ between the PRC (revisionist state) and the United States of America (hegemonic state), and thereby satisfy the cardinal precept for the onset of “hegemonic war” as described in Organski’s thesis. 5,6

Furthermore, any solution to the issue would set a precedent, in both normative as well as symbolic terms, for the settlement of other sovereignty claims upheld by Japan and China vis-à-vis other countries. As such, the conflict presents a crucial study from the strategic point of view.

Most importantly, the Senkaku/Diaoyu problem in several ways highlights the fundamental inconsistency between the claims of sovereignty based in 14th century Asia, and the norms of international dispute settlement developed in Europe centuries later. This divergence owes to the fact that the traditional East Asian international system that existed until the late 19th century entailed extremely different connotations regarding the concepts of sovereignty and territorial boundaries than those enshrined in the modern Westphalian system. Unlike the Westphalian system that institutionalized norms regarding the notions of sovereignty, diplomacy, nationality, and commercial exchange, traditional East Asian international system operated within the dynamics of the Confucian world view. As such, the traditional East Asian regional order was patterned along a hierarchical construct, with China as the hegemonic power. Within this system, states derived their status and ranking from their cultural achievements, rather than military or economic prowess. Moreover, as David C. Kang has demonstrated, demarcation of uninhibited rocks in the middle of water bodies was not a practice in the East Asian region five hundred years ago. Therefore, Kang asserts that most of the current debates over different Islands in East Asian waters are political disputes and not historical issues per se.7 Therefore, it is imperative for IR analysts to explore the dynamics of the East Asia regional construct pertaining to this period, and argue the legitimacy and applicability of the concept of ‘sovereignty’ based upon this ancient regional order.

The Senkaku/ Diaoyu Dispute: Core Issues

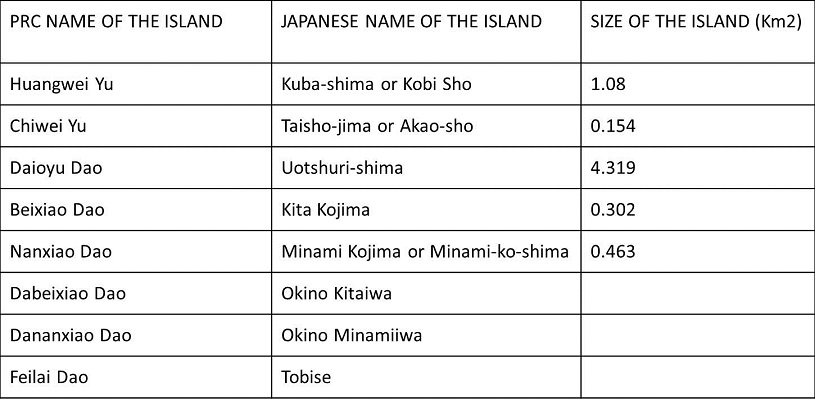

The Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands refer to a tiny group of islands, comprising a land area of 6.3 Km2, in the East China Sea. The islands consists of eight tiny insular formations, of which only two are over 1 Km2 (the Diaoyu/Uotusri Island is the biggest one with a land area of 4.3 Km2), five are completely barren, and none are currently inhabited or have had any kind of reported human activity.

At the outset, the Islands dispute primarily involves two fundamental issues: the question of sovereignty over the disputed islands; and the issue of demarcation of the maritime boundary between Japan and China. These issues are further exacerbated due to a complex construct involving security, economic, and political concerns.

The “territorial” aspect of the conflict essentially emanates from a divergent reading of history by both China and Japan. It is within the context of historicity that the dispute assumes a symbolic significance. For the Chinese, the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute represents yet another legacy of Japanese war-time aggression against China.9 As such, any resolution to the islands issue from the Chinese side would be conceived within the dynamics of convergence between pragmatic concerns of economics and security, and the politics of Chinese nationalism derived from a collective memory of past humiliation.

Similarly, Japan regards the developments of the late 19th century pertaining to its annexation of Ryukyu Islands, Bonin Islands as well as the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands to be lawful territorial consolidations, and unrelated to its overseas military ventures or imperial expansion. 10 As such the sovereignty dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands is associated with the idiom of national pride for the Japanese. This interplay between territorial disputes and popular nationalism serves to limit the policy choices for resolving the sovereignty debate by both countries.

The issue of demarcation of the maritime boundary is rooted in the specific geographic features of the East China Sea. Under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCOLOS), the territorial waters of states extend up to a limit of 12 nautical miles from their baseline. Further, the states can also claim a sea area of 200 nautical miles from the baseline as their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).11 However, this delineation becomes complicated in the case of East China Sea as the coast-to-coast distance is less than 400 nautical miles (only 360 nautical miles). Ownership of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands would enable China to exert sovereign rights over the continental shelf along with the EEZ to the north and east of the disputed Islands. This would allow China exclusive economic rights to the entire southern portion of the East China Sea. Likewise, sovereignty over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands would entitle Japan to extend its EEZ to the north and west of Islands, beyond the Okinawa Trough.12

The maritime boundary aspect of the Islands dispute is further rendered difficult due to the differing interpretations of international laws pertaining to the seas by the claimant states. Whereas, Japan stresses on the ‘equidistance principle’ to demarcate the maritime boundary between China and Japan, the Chinese insist on the ‘principle of natural prolongation’ to solve the boundary question.13 As per Article 76 of the UNCLOS, a coastal state can claim an area up to 350 nautical miles from its baseline as its extended continental shelf under the principle of ‘natural prolongation’. The coastal state has the sovereign rights to explore mineral and non-living resources in the subsoil of the continental shelf. China argues that the Okinawa Trough in East China constitutes the natural maritime boundary between the PRC and Japan, and hence claims the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as falling within the 350 nautical miles area of its continental shelf that extends from its coast to the Okinawa trough. However, Japan insists that the Okinawa Trough is only an “incidental impression in an otherwise continuous continental shelf” and therefore, cannot constitute a natural maritime boundary. Accordingly, Japan favours an equitable division of the waters of the East China Sea by drawing a median line that is equidistant from the baseline of Chinese coast and the baseline of the Ryukyu Islands.14

For the feasibility of this study, the Paper will restrict itself to exploring the political, security and economic dimensions of the problem. In order to achieve this stated objective, the study shall explore and debate the historical documents cited by the both China and Japan to justify their claims over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets.

Various Dimensions of the Issue: Interplay between Political, Security, and Economic Concerns

The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands are located approximately midway between Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands, around 120 nautical miles northeast of Taiwan, 200 nautical miles southwest of Okinawa, and 230 nautical miles east of China. This particular location of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands underscores the security dimension of the dispute. Sovereignty over the contested Islands would enable Japan or China to project its military prowess along a prolonged and enlarged frontier, thereby putting the other side into a disadvantageous position.

Furthermore, the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute also entails geopolitical implications for both China and Japan. The sovereignty issue over the Islands involves a crucial relationship with PRC’s ‘One China’ policy. China regards the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as part of Taiwan, and validates its rights over the Islands on the basis of its claim over the ROC. As such, loss of sovereignty debate over the disputed Islands would jeopardise its concerns in Taiwan as well. It is in the context of Taiwan that the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute gets associated with the notion of regime stability in China. In the words of Chinese scholar, Zhongqi Pan, “If the Chinese government wavers in its position on the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands, its legitimacy would be immediately challenged by the Chinese people in both the mainland and Taiwan.” 15

Moreover, as stated above, any solution to the Islands issue would set a precedent for the resolution of China’s claims in the South China Sea in particular, and its territorial disputes with other countries in general. Similarly, for Japan the issue holds consequences for its differences with Russia over the “Northern Territories” and with Korea over the Dokdo (Takeshima/Takdo) Island.

Notwithstanding the security and political significance of the Islands to the claimant states, the current dispute traces its origin to the 1968 report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and Far East (ECAFE). The report by the ECAFE suggested the possibility of large hydrocarbon deposits in the waters off the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. As such legal control over the Islands would confer upon the owner nation the “exclusive rights” to exploit the natural resources in the vicinity of the Islands. The economic value of the Islands should be of particular concern to China whose oil consumption is already the second largest in the world. According to some estimates, China’s oil consumption is expected to reach 590 million metric tonnes by 2020, nearly three-quarters of which will be imported by that time.

The Dispute: Legacy of Post-Second World War History

The recent history of the Senkaku/Dioyu dispute is located within the dynamics of international politics in the post-World War II period. This international political scenario is characterized by international treaties concerning the status and transfer of various territories, trans-regional alliances, and the changing contours of East-Asian politics and economy.

The current dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands began with the 1969 US-Japan joint statement16 that culminated in the Ryukyu Reversion Agreement of June, 1971. 17 As per this agreement, the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands were returned to Japan as part of the Okinawa. Previously, the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands had been placed under the US administration as part of the Nansei (Ryukyu) Islands in accordance with Article III of the 1951 San Francisco Treaty. Article III of the San Francisco Treaty stated18,

“Japan will concur in any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system, with the United States as the sole administering authority, Nansei Shoto south of 29 north latitude (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands)…. the United States will have the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over the territory and inhabitants of these islands, including their territorial waters.”

The US-Japan joint statement immediately triggered nation-wide protests by Chinese students in the United States.19 On June 1, 1971, the Republic of China (ROC) Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a formal statement laying down Taiwan’s claim over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets on the basis of history, geography, and the principle of long usage of the Islands by the Taiwanese peoples. The ROC further adduced the provisions of the 1943 Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration of 1945, and the1952 Treaty of peace between the ROC and Japan to legitimize its claims over the disputed Islands 20 This aspect of the problematic involving the relationship between the Islands dispute and aforementioned treaties will be discussed in detail later in the Paper.

Meanwhile, in November 1970, the Japanese government had proposed the ROC and South Korea to carry out ‘joint development’ of the undersea resources in the East China Sea. This joint development exercise was to be conducted without any reference or prejudice to the sovereignty claims of the participant nations in the East China Sea.21 It was at this juncture that the PRC entered into the dispute through an article in the Peking Review in December 1970. The article accused the United States and Japan of setting up a “liaison committee” to plunder Chinese and Korean seabed resources in “collusion” with the “Chiang Kai-shek Gang and Pak Jung Hi puppet clique”. The article further stated that “...supported by US imperialism, the reactionary Sato government is also seeking various pretexts for incorporating the Tiaoyu, Huangwei, Chihwei, Nanhsiao, Peihsiao and others, as well as water areas which belong to China, into Japan’s territory.”22

The PRC Foreign Ministry issued its formal statement with respect to the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue in December 1971. The statement for the first time stated China’s legal status on the dispute, and declared:23

“…..the Tiaoyu and other Islands have been China’s territory since ancient times. Back in the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1368-1644), the Islands were already within China’s sea defence areas; they were islands appertaining to China’s Taiwan but not to Ryukyu….Like Taiwan, they have been an inalienable part of Chinese territory since ancient times….The Chinese people are determined to recover the Tiaoyu and other Islands appertaining to Taiwan.”

As can be inferred, the statement inextricably linked the Senkaku/Dioyu dispute to China’s claims over Taiwan, and thus rendered the issue a central significance within China’s political apparatus.

The year 1972 served as the watershed year for the Senkaku/Dioyu Islands dispute. In 1972, the US ended its trusteeship of the Islands and formally returned the Islands to Japan. Following U.S President Richard Nixon’s rapprochement towards China and the subsequent visit to Beijing in 1972, both China and Japan embarked on the negotiations that led to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries.24 Pursuant to this development, Japan severed its relationship with the ROC in 1972. This political realignment thus changed the contours of the conflict from being a ROC-Japan issue to a dispute between the PRC and Japan.

It is within the ‘apparent peace’ build-up between China and Japan that yet another strand of the Senkaku/ Diaoyu dispute emerged. The Chinese claim that during the normalization talks in 1972, there was a ‘tacit agreement’ between Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka and Chinese Premiere Zhou Enlai to shelve the Island issue. However, Japan argues that it never reached an agreement with China about "shelving" or "maintaining the status quo" regarding the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands.25 As such, Japan does not recognize the existence of any issue regarding the territorial sovereignty of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.

On the Contrary, the Chinese version of the same conversation, made public only in 2012 through an article in the People’s Daily argues that both Zhou and Tanaka decided to stall the issue for future negotiations and deliberations.26 Through this interpretation of the conversation, China attempts to showcase the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets as a ‘mutually recognized’ disputed territory.

Understanding the Claims: The Politics of History

Within the framework of the dispute both China and Japan agree on the fact that Japan exercised the de facto control of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands from1895 until the end of the Second World War. While Japan emphasizes this period of undisputed Japanese administration to assert its claims over the disputed Islands, the Chinese base their arguments on the pre-1895 period when they claim to have occupied the Islands. To support their claims, both countries take recourse to various international and bi-lateral treaties. This divergence in interpretation of history and legal documents pertaining to the issue necessitates a study of the arguments of both claimants.

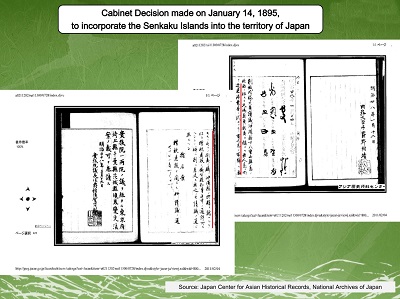

In 1870s, Japan annexed the Ryukyu (present day Okinawa) Kingdom. However, it refrained from laying any claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands till 1895, when it finally annexed the Islands through a Cabinet decision (Appendix I). During the period between 1895 and the Second World War, Japan administered the disputed Islands as part of the Okinawa prefecture.

China argues that Japan took possession of the Islands after the defeat of the Qing court in the 1894 Sino-Japanese War. The PRC asserts that as the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets appertained to Taiwan (formerly Formosa), the Islands were ceded to Japan as part of the Formosa Island under Article II of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, concluded between Qing China and Japan in May 1895. Article II of the Treaty of Shimonoseki stated:27

“China cedes to Japan in perpetuity and full sovereignty the following territories, together with all fortifications, arsenals, and public property thereon….2(b) The Island of Formosa, together with all islands appertaining or belonging to the said island of Formosa…..2(c) The Pescadores Group, that is to say, all islands lying between the 119th and 120th degrees of longitude east of Greenwich and the 23rd and 24th degrees of north latitude….”

Hence, China stresses that the Islands should be returned to it as per the provisions of the 1943 Cairo Declaration, and the Potsdam Conference of 1945. Signed in November 1943, The Cairo Declaration proposed,28

“They [the Allies] covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansion. It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed.”

The Potsdam Declaration, signed in July 1945 further reinforces the terms of the Cairo Declaration. Article 8 of the Declaration reads:29

“The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.”

However, Japan refutes the Chinese assertion that the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands were included as part of the Taiwan and Pescadores (Penghu) Islands annexed by it under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. As per the Japanese claims, the cabinet decision to occupy the Islands in 1895 was the result of a 10-year-long survey on the disputed Islets, which confirmed that the Islands showed no trace of having been under the control of China. Based upon this argument, Japan claims that the Islands were occupied by it under the principle of terra nullius (land without owners) as enshrined in the modern international law on territorial acquisition. As such, Japan maintains that the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands were never included in Article II of the 1951 San Francisco Treaty, whereby Japan denounced its claims over ‘Formosa and the Pescadores Islands’ or the 1952 Treaty of Peace between the ROC and Japan which reiterated Article II of the San Francisco Treaty, and further declared that “…all treaties, conventions, agreements concluded before December 9, 1941, between China and Japan have become null and void as a consequence of the war.”30

Japan further argues the PRC and Taiwan only began laying their claims over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands after the discovery of the prospective petroleum resources in the Senkaku/Diaoyu seabed. To consolidate this argument, Japan stresses the fact that neither Beijing nor Taipei ever raised any objections against the exclusion of the disputed Islands under Article II of the San Francisco Treaty. Also, both China and Taiwan never protested against Article III of the said Treaty, whereby the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets were transferred to the US as part of the Okinawa. However, this argument from the Japanese side is refuted by China on the grounds that the San Francisco Peace Treaty cannot exert finality on the dispute as neither the PRC nor Taiwan were signatories to the treaty.

To justify its claims, Japan cites historical documents which describe the disputed Islands as its territory. Two such documents pertain to the maps published in the Republic of China New Atlas, and the World Atlas, both published in China in 1933 and 1958 respectively. Both these maps depict the disputed Islands as the “Senkaku Islands” and not Diaoyutai Islands (See Appendix II, III).

Other documents put forth by Japan to reinforce its claims include a 1953 article that appeared in the People’s Daily and which describes the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as part of the Ryukyu Islands (See Appendix IV). Another important article cited by Japan vis-à-vis their claims over the disputed Islands appertains to a 1920 ‘Letter of Appreciation’ by the Consul of the Republic of China in Nagasaki to the Japanese citizens to thank them for helping the Chinese fisherman in distress. The letter refers to the Senkaku Islands as part of the Okinawa Prefecture (Appendix V). However, it must be noted that China refutes the relevance of this evidence on the grounds that since the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, along with Taiwan were already under the Japanese control from 1885, the Consul referred to them as being Japan’s territory.

In addition to employing maps and official correspondences, Japan also takes recourse to historicity to justify its claim over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Japan posits that Formosa was not exactly under the control of the Fujian province during the Ming dynasty. It was only in 1683, under the Qing that Formosa was included in the Chinese territory.31 Through this interpretation of history, Japan seeks to nullify the Chinese claim that the Islands were China’s territory during the Ming rule.

As against the Japanese arguments, the Chinese claims to the Islands emanate from the historical narrative of the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) periods. Chinese historical records detail the discovery and geographic features of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as early as 1372. During this period, the Islands were used as navigational aid for the official Chinese missions to the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was in a tribute relationship with China at that time. As per the Chinese records, during the period from 1372-1879, the Chinese Emperors sent some 24 investiture missions to the Ryukyu Islands to confer the title of Zhongshan Wang (the Chung-shan King) on their new rulers.32 China also argues that the name “T’iaoyutai” first appeared in a Chinese book entitled Shun-feng Hsiang-sung (May Fair Winds Accompany You) published in the fifteenth century.33

China insists that the Islands were incorporated into its maritime defence as early as 1556. Some of the documents cited to support this claim by the Chinese include the Illustrated Treatise on Coastal Defence. Compiled in 1562, the volume recorded all Chinese military deployments in the coastal areas on the mainland and offshore Islands. The disputed Islands were recorded in two maps labelled Fu7 and Fu8 in the first scroll of the volume whose title is “Atlas of the Islands and Shore of the Coastal Region.” (Appendix VI). Likewise, the Revised Gazetteer of Fujian Province complied in 1871 indicates the presence of the “Diaoyutai” behind Taiwan, and their utility to anchor large ships (Appendix VII).

Interestingly, China employs studies by certain Japanese scholars to augment its claims over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets. Two prominent works in this regard are the 1785 map drawn by noted Japanese cartographer, Hayashi Shihei, titled the Illustrated Survey of Three Countries; and a study by Japanese historian Inoue Kiyoshi, “Senkaku” Islands: A Historical Explanation of the Diaoyu Island. The map by Hayshi Shihei uses the traditional four pigment colouring method, with Chinese territories, including the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands marked in red (Appendix VIII). This map was further translated into French and published in 1832 by a German scholar of Oriental studies, Heinrich Klaproth. The book by Inoue Kiyoshi cites several documents pertaining to the Ming period to establish Chinese sovereignty over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets.34

In addition to this, China cites certain official Japanese documents which indicate that Japan was aware of the fact that the Islands were not terra nullius. One such document relates to an October 21, 1885 letter of response by the Foreign Minister of Japan to the Home Ministry (Appendix IX). The letter states that the Islands bear Chinese names and that a Chinese newspaper has already carried a report regarding Japan’s intentions to occupy the Islands near Taiwan. It further requests the government to wait till the “appropriate” time to establish its claim over the Islands.

China also argues that the ten years investigation by Japan to ascertain the status of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets was never completed. This assertion is supported through a letter written by the Okinawa Prefectural Governor 1892. In the letter, the Governor states that since the initial investigations of 1885, no subsequent field surveys have been conducted on the Islands (Appendix X).

The Chinese also refer to some usage of the disputed Islands as evidence of their claim. One such interesting record is that in 1893, just two years before Japan occupied the Islands, Dowager Empress Tsu Hsi of Qing issued an imperial edict through which the Islands were awarded to a Chinese alchemist who had gathered rare medical herbs on the Islands.35

Analysis of the Claims:

In addition to establishing the authenticity of the documents produced by both China and Japan to assert their claims over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islets, the dispute calls for an examination of the concept of ‘ownership’ over the Islands within the dynamics of the antiquated historical narratives of the countries. Within this context, a careful study of China’s claims reveals that the disputed Islands have been mentioned in the Ming historical records only for the purpose of navigational aid between the imperial court and the Ryukyu Kingdom. Moreover, China never established a permanent settlement of civilians nor of military personnel on the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Therefore, it can be deduced that China never established any ‘direct’ ownership over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. On the contrary, Japan exercised de facto control over the disputed Islets for a period of fifty years, beginning from 1895 to the end of the Second World War in 1945.

The second aspect of the problematic concerns the economic dimension of the dispute. In this respect, it is significant to question China’s failure to object to article II, and III of the 1951 San Francisco Treaty. The Chinese argument that neither Taiwan nor the PRC were signatories to the Treaty fails to explain China’s silence on the matter for almost two decades. It is within these dynamics that China’s claims over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, originating only after the discovery of possible hydrocarbon deposits in the waters off the disputed Islets, indicate a classic case of economic opportunism.

APPENDIX I

APPENDIX II

APPENDIX III

APPENDIX IV

APPENDIX V

APPENDIX VI

APPENDIX VII

APPENDIX VIII

APPENDIX IX

APPENDIX X

Endnotes

- John A. Vasquez, The War Puzzle (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- For a detailed study of Nationalism and its effects upon China’s territorial disputes refer to, Erica Strecker Downs and Philip C. Saunders, “Legitimacy and the Limits of Nationalism,” International Security, Vol. 23, No.3 (Winter, 1998-1999), pp. 114-146; Chih-Yu Shih, “Defining Japan: The Nationalist Assumption in China’s Foreign Policy,” International Journal, Vol.50, No.3 (Summer 1995), pp. 543-544; Erik Beukel, “ Popular Nationalism in China and the Sino-Japanese Relationship,” Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) Report 2011:01.

- This modeling of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute is based upon Johan Galtung’s Conflict Triangle. For details See, Johan Galtun, Theories of Conflict: Definitions, Dimensions, Negations, Formations ( Columbia University: 1958)

- China first claimed the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as its Core National Interest through an opinion piece in the People’s daily in January 2012. The article can be accessed at http://english.people.com.cn/90780/7708939.html. The PRC officially declared the disputed Islands as its core national interests in April 2012, through a statement by the Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Hua Chunying. China uses the term to describe its sovereignty claims over Taiwan, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, and Tibet.

- A.F.K Organski, World Politics ( New York: Knopf, 1968)

- The Paper employs Organski’s thesis only as an idea among various schools of IR theories to explain States’ behaviour. The author neither subscribes to, nor endorses the Realist perspective.

- David C. Kang, East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute ( New York: Columbia University Press, 2012)

- Names and size details of the Islands taken from Che-jung Yu, “A Historical Analysis of the Ownership of the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands: from the Chinese Perspetive,” Mater’s Thesis, Graduate School of International Affairs, Ming Chuan University, 2013; Daniel Dzurek, “The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Dispute,” Paper available at http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk/resources/docs/senkaku.html

- “Diaoyu Dao: An Inherent Territory of China,” State Council Information Office, PRC, September 2012. Full text available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-09/25/c_131872152.htm

- “The Basic View on the Sovereignty of the Senkaky Islands,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. Full text available at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/basic_view.html

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, available at http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- Pan Zhongqi, “Sino-Japanese Dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: The Pending Controversy from the Chinese Perspective,” Journal of Chinese Political Science, Vol. 12, No.1, 2007

- The Principle of Natural Prolongation proposes that a nation’s maritime boundaries should reflect the ‘natural prolongation’ of where its land territory reaches the coast. Whereas the Equidistance principle refers to a legal concept that states that a a nation's maritime boundaries should conform to a median line equidistant from the shores of neighboring nation-states.

- For a detailed discussion on this aspect of the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute, See, Peter Dutton, “Craving Up the East China Sea,” Naval War College Review, Spring 2007, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp.45-68.

- ibid

- “Joint Statement of Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato and U.S. President Richard Nixon,” November 21, 1969, Washington, available at http://www.ioc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~worldjpn/documents/texts/docs/19691121.D1E.html

- “Agreement Between the United States of America and Japan Concerning the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands,” June 17, 1971. Document is available at the Ryukyu-Okinawa History and Culture Website, http://www.niraikanai.wwma.net/pages/archive/rev71.html

- “Treaty of Peace with Japan,” signed at San Francisco, September 08, 1951, United Nations Treaty Series 1952 (reg. no. 1832), vol. 136, pp. 45 - 164.

- “An open letter to President Nixon and members of the Congress,” The New York Times, May 23, 1971.

- The original statement was published in Chinese in Chung-yang Jih-pao ( Central Daily News), June 12, 1971. Cited here from Hungdah Chiu, “An analysis of the Sino-Japanese Dispute over the T’iaoyutai Islets (Senkaku Gunto),” Occasional Paper Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, School of Law, University of Maryland, No. 1, 1999.

- Ibid 17

- “US and Japanese reactionaries out to Plunder Chinese and Korean Sea-Bed Resources,” Peking Review, Vol. 13, No. 450, December 11, 1970.

- “Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China,” (December 30, 1971). English translation available in Peking Review, Vol. 15, No.1, January 7, 1972.

- “Joint Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Japan,” Peking Review, Vol. 15, No.40, October 6, 1972.

- “The Senkaku Islands,” Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, Japan, November, 2012, available at http://www.lk.emb-japan.go.jp/eg/contents/culture/SenkakuIslands.pdf

- “Diaoyu Islands are Chinese territory, based on abundant iron-clad evidence,” People’s Daily, October,

12, 2012, available at (http://www.chinaembassy.org/chn//zt/DiaoYuDao/t978666.htm). - “Treaty Of Shimonoseki,” April 17, 1895, available at http://www.taiwandocuments.org/shimonoseki01.htm

- United States Department of State. A Decade of American Foreign Policy: 1941-1949, Basic Documents. Washington, DC: Historical Office, Department of State; for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. G.P.O., 1950, p. 20.

- ibid

- “Treaty of Peace between the Republic of China and Japan,” April 28, 1952, Taipei, available at http://www.taiwandocuments.org/taipei01.htm

- “The Senkaku Islands,” Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, Japan, November, 2012, available at http://www.lk.emb-japan.go.jp/eg/contents/culture/SenkakuIslands.pdf

- Tao Cheng, “The Sino-Japanese Dispute Over the Tiao-yu-tai (Senkaku) Islands and the Law of Territorial Acquisition,” Virginia Journal of International Law, Vol.14, No.2, 1974, pp.248-260.

- The Year of publication of this book is not clear. According to Joseph Needham, it was published in 1430. For further details, see Science and Civilization in China, Vol.4, Part 1, Chapter 26, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971)

- Kiyoshi Inoue, Japanese Militarism & Diaoyutai (Senkaku) Island–A Japanese Historian’s View: ‘The Tiaoyu Islands (Senkaku Island) are China’s Territory. Full text available at http://www.skycitygallery.com/japan/diaohist.html

- Tao, “The Sino-Japanese Dispute,” 1974, pp. 248-60

Published Date: 12th June 2014, Image source: http://www.bloomberg.com

Post new comment