Introduction

Since 1948, when Sri Lanka became free from British rule, it has enjoyed a close and cordial relationship with Pakistan. Sri Lanka openly supported Pakistan during the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan. During the Indo-Pak war of 1971, Colombo provided transit and refueling facilities to Pakistani war planes, knowing fully well that they will be used against India. The country also played an important role in the restoration of Pakistan to the Commonwealth.1 It was Sri Lanka’s resolve in 2009, to play cricket in Pakistan despite security warnings that helped prevent Pakistan’s isolation in the field of international cricket.2 The island’s team did face a terrorist attack in Lahore, though no player was killed or injured.

The relationship is ‘multi-faceted’3 and multi-sectoral, given their wide-ranging bilateral discussions on and cooperation in various fields including trade, education, science and technology, culture, pharmaceuticals, engineering, railways, tourism, diplomatic training and defense.4 One does not have to go too far to seek the reason for such diverse interaction. Sri Lanka does not want to look at everything through the Indian prism and Pakistan proves to be an excellent alternative. Besides, Pakistan’s closeness with China has helped Sri Lanka not only in getting aid and assistance from both the countries, but also in keeping India in check. Sri Lanka’s fear psychosis related to India go back to the mid-1940s when some Indian leaders, including Nehru, suggested a closer union between India and Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was then known), presumably with the latter as an autonomous unit within the Indian federation.5

A common strand in their relationship was highlighted by the Pakistan Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz during his visit to Sri Lanka in 2004. He said: “Our relations are rooted in antiquity, shared cultures, values and sense of common destiny. Pakistan and Sri Lanka thus needed to renew the multiple bonds of friendship.”6 However, notwithstanding the depth of their relationship, a question mark remains on the post-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) era status of Sri Lanka-Pakistan ties.

Economic Cooperation and Free Trade Agreement

Sri Lanka and Pakistan have realised that their relations, based on mutual trust and confidence, has not been reflected in health, trade and commercial fields.7 Even before Free Trade Agreement (FTA) was signed on August 2, 2002 efforts were made by the two countries to shore up their trade. In 2004, Pakistan offered US $10 million to Sri Lanka to buy Pakistani products and signed an agreement to this effect during President Chandrika Kumaratunge’s visit to Pakistan in February 2005.8 It was agreed that Sri Lanka would import rice from and export tea to Pakistan. The latter also offered to export engineering goods, fans and air conditioners to Sri Lanka9 and agreed to provide assistance in the field of banking, telecommunications and Information Technology. As for Pakistan, it has long been keenly interested in Sri Lanka’s expertise in the textile and garments sector as well as the gem and jewellery industry.10 In 2005, an agreement to establish direct air links between Islamabad and Colombo, and Lahore and Colombo was signed as a sequel to the Free Trade Agreement (FTA); the frequency of the flights operating between Karachi and Colombo was increased from six to ten per week.11

During President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s visit to Islamabad in 2006, Sri Lanka offered another credit line of US$ 10 million to the Pakistani business community to facilitate import of products from Sri Lanka.12

A bilateral trade agreement has existed between Sri Lanka and Pakistan since 1984. However, it was during the 9th session of the Sri Lanka – Pakistan Joint Commission meeting in Colombo on May 12-13, 2005 that the two countries for the first time exchanged notes confirming to each other the completion of the domestic legal procedures for putting the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) into practice. The groundwork was thus prepared and it was made operational as of June 12, 2005. Sri Lanka became the first country in South Asia to sign a free trade pact with Pakistan. Pakistan agreed to provide 100 per cent duty concession on 206 commodities, including frozen fish, vegetables, spices, fruits/juices, polymers of vinyl chloride in primary forms, natural rubber, raw silk, tanned/crust skins, wool, some varieties of paper and board, carpet and floor covering, non-alloy aluminum, iron and steel products and toys/dolls, with immediate effect. Likewise, Sri Lanka also waived duties immediately on 102 items, which include chickpeas, dates, oranges, benzene, toluene, apparel and clothing accessories, ball bearings, penicillin/streptomycin/tetracycline and their derivative and vacuum flasks.

It was further decided to eliminate custom tariff on almost 90 per cent of products over the next five years, as also to grant tariff rate quotas (TRQs) and higher margin of tariff preferences to each other on a number of products in a bid to keep the negative list as short as possible. Both countries have agreed to a 35 per cent domestic value addition and change of tariff heading at six digit level, which will provide flexibility for Sri Lankan and Pakistani investors to source their inputs from third countries and export manufactured products to each other.13

In 2007, within two years since the signing of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the trade between the two countries has shown a 27 per cent increase in volume.14 An overall improvement in 2008 was noted when exports from Sri Lanka recorded a rise of 81 per cent and imports from Pakistan registered a growth of about 78 per cent.15 No wonder, the two-way trade volume reached US$ 230 million in 2005-0616 and peaked at US$ 385 million in 2008.17 Both sides, however, agreed to raise the bilateral trade figures to US$ 1 billion by 2010-11.18 Sri Lanka had also expressed its desire to benefit from the expertise of Pakistan in the field of oil exploration.19

Of late, Pakistani businessmen have begun to look at Sri Lanka for its resource markets, especially after the fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Business opportunities beyond the Free Trade Agreement are being explored. The meeting of the first inter-governmental committee looked at the possibilities of including services sector within the ambit of the Free Trade Agreement.20 Besides, talks to sign a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) to broaden the scope of the Free Trade Agreement were also in its last stages, though there have been some political objections from Sri Lanka.

With India, however, no such progress in economic ties can be seen, although India has renewed its offer to revive Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) which aims at expanding cooperation in investment and services with Sri Lanka after the coming of the stable government in power. Opposition to Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (with India) in Sri Lanka is on nationalist, rather than economic grounds (Liyanage, Sumanasiri 2010, 66).21 With Pakistan however, no such ‘fear factor’ is at work in Sri Lanka. In fact, Pakistan is the only South Asian country besides India with which the island republic has a Free Trade Agreement. Although trade figures are not very impressive, the pace of improvement is noteworthy. To which “agreed” Muhemmed Aejaz, Pakistan’s Trade Counsellor in Colombo, who viewed Sri Lanka-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (SLPFTA) as more advantageous to the Sri Lankan business community than its agreement with India (Sri Lanka-India Free Trade Agreement (SLIFTA).22 The reason for this is that although with India, Sri Lanka’s trade has reached US$ 2 billion, the balance of trade is heavily in favour of India. The Sri Lanka-Pakistan trade also tilts in favour of the latter, still their economic relationship can be seen as a two-way process in which both the partners are equally contributing towards its success. “Negative trade balance is not always negative. It should be seen in the broader context” said the Head of the Chancery of the Pakistan High Commission in Sri Lanka, Balal Akram.23 While the share of Sri Lankan exports to Pakistan has shown a big jump – from US$ 44.86 million in 2004-05 to more then US$ 71 million in 2005-06, 24 Pakistan’s exports to Sri Lanka also reached US$ 214 million in 2007-08 from US$ 97.8 million in 2003-04 after the Free Trade Agreement became effective in 2005.25 It is far more mutually beneficial than the island’s trade dealings with India in which there are huge item gaps and wide exim margins.

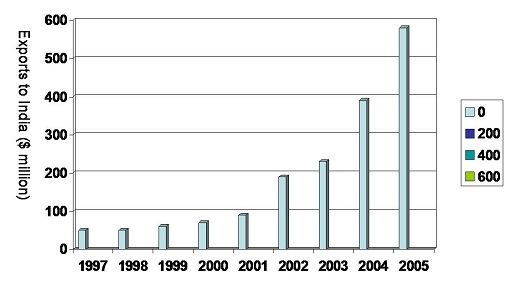

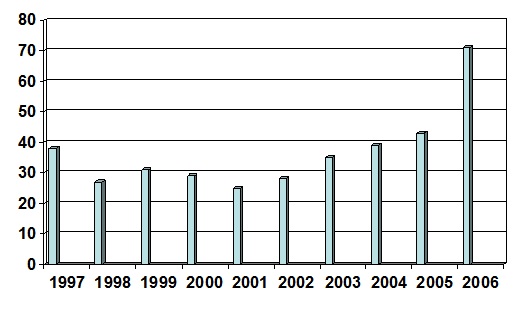

Given below are the two graphs sourced from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s Annual Report, 2005. The first graph shows an unprecedented increase in Sri Lanka’s exports to India in a period immediately following the signing of the Free Trade Agreement in 2002. However, exports figures for preceding period with India were not very encouraging. The Pakistan graph shows that the level of Sri Lanka’s exports remained consistently high even before the Free Trade Agreement in 2005. A year after the signing of the Free Trade Agreement, the volume of Sri Lanka’s exports to Pakistan registered a steep rise to US$ 71 million, generating hopes among the Sri Lankan business community from their interactions with the Pakistani counterparts.

Exports to India ($ Million)

Exports to Pakistan ($ Million)

Notwithstanding the impressive trade statistics, it is a matter of concern that some Sri Lanka’s products in which it has a natural advantage, like cotton textiles and apparels, tea and rubber, have been put on the negative lists of India and Pakistan.26 A quick look at the list of items exported to India and Pakistan shows a high concentration of vegetable oils, insulated copper products, copra and smoked sheets (natural rubber).27 This shows that the growth in bilateral trade is highly selective and not diversified.

Another aspect of Sri Lanka-Pakistan economic relationship is the sharing of the vital commercial intelligence inputs. “We have done extensive studies on commercial intelligence and are prepared to share vital information with a friendly country such as Sri Lanka”, the Director General of Pakistan’s Trade and Development Authority, Nusrat Iqbal Jamshed has said.28 With the frequent exchange of high level business delegations, Sri Lanka and Pakistan are making rapid strides to boost their bilateral economic ties.29

Sri Lanka – Pakistan Defence Ties and Military Cooperation

Sri Lanka has an excellent defence relationship with Pakistan, which provides the former with military hardware.30 During the course of Sri Lanka’s war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, Pakistan has emerged as one of the leading small weapons suppliers to the island nation. When Pakistan Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz visited Colombo in 2004, Chandrika Kumaratunga, then the President of Sri Lanka, expressed her gratitude for the assistance her country had received in the field of defence.

The defence partnership began in 1999, when Pakistan offered a credit line (US$ 20 million) to Sri Lanka for procurement of defence equipment.31 In November 2004, both sides agreed to strengthen cooperation in this field and to review the credit line with a view to its operationalisation during a visit by the then Sri Lankan President Kumaratunga to Pakistan.32 The total purchases till December 2007 were to the tune of US$ 50 million. There was a sudden jump in the quantity of merchandise ordered in 2008 due to the escalation of the ethnic war.33 In 2008, during a meeting between Sri Lanka’s Lt. General Sarath Fonseka and his Pakistani counterpart General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani, Pakistan agreed to supply 22 Al-Khalid Main Battle Tanks (MBT) worth US$ 100 million, besides high-tech weapons.34

Fonseka’s shopping list to the Pakistani military authorities were put at US$ 65 million under which the inventory for the Lankan Air Force alone was worth US$ 40 million.35 He had further sought 250,000 rounds of 60 mm, 81 mm, 120 mm and 130 mm mortar ammunition worth US$ 25 million and 150,000 hand grenades for delivery within a month to the Sri Lankan Army.36 It was also agreed that Pakistan will send one shipload of the items needed every 10 days to bolster the Lankan military efforts to take over Kilinochchi, the administrative centre of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.37 According to Jane’s Defence Weekly, Sri Lanka had also made a plea to Pakistan to provide swift technical assistance for its T-55 Main Battle Tanks and C-130 transport aircraft.38 In 2006, in a bid to show their displeasure against the growing defence ties between Sri Lanka and Pakistan, Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam blasted a convoy carrying the Pakistani High Commissioner to Sri Lanka, Bashir Wali Mohamand, who narrowly escaped the attack.39 Four of his bodyguards were however, killed.

Media, especially in Pakistan, has attributed Sri Lankan forces’ victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam to the generous Pakistani assistance and the active participation of many seasoned Pakistani air force pilots in Sri Lanka’s military operations,40 though both the countries were vehement in their denial. This is contrary to Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s contention that India was providing military support to Sri Lanka. Notwithstanding Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s false pretensions and displeasure over their growing bilateral bonhomie, in January 2009, the two countries i.e. Sri Lanka and Pakistan agreed to enhance their cooperation in the field of military training, exercises and intelligence-sharing, so as to counter terrorist threats jointly within the region.41

The governments of Sri Lanka and Pakistan also select their envoys on the basis of the relevance of their background and experience to the prevalent needs of each other’s countries. In 2006 Pakistan sent Bashir Wali Mohamand, as the envoy, keeping in mind his experience as a Director General of the Intelligence Bureau (Pakistan) when the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka was at its peak. In 2006, Pakistan selected another military man Air Marshal (retd.) Shehzad Aslam Chaudhary for the High Commissioner’s post so that he could function as hands on adviser to the Sri Lankan Air Force.42 For its part, Sri Lanka sent Air Marshal Jayalath Weerakody as the High Commissioner to Pakistan in 2009, when the tribal uprising was at its peak in Swat and other tribal areas. Such engagements have been more military than diplomatic, 43 as it was meant to help each other with intelligence and counter-intelligence operations.

Pakistan has been engaged in providing military training to Sri Lankan armed personnel at its premier defence colleges.44 Pakistan Military Academy’s intake was 48 and 50 cadets from Sri Lanka in 2007 and 2008 respectively, which is one of the largest in foreign cadets’ category.45 During a goodwill visit to Sri Lanka, the captain of Pakistan’s newly acquired Chinese-built guided-missile frigate, P.N.S. Zulfiquar, told the media that his country was training 70 Sri Lankan naval personnel annually. He said his country would be giving small frigates46 to the Sri Lankan Navy to patrol its coastlines that are prone to intrusion by Indian fishermen. The Pakistan Navy, he added, has offered several berths to the island states’ naval personnel for advanced training in its prestigious establishments, on an annual basis.47

The defence cooperation peaked during the ethnic conflict, when Pakistan supplied small arms and ammunition and provided training to Sri Lanka’s military personnel. Such interactions brought the two countries closer than ever before. N Godage, a former Sri Lankan diplomat, said during an interview that he could boldly say that Sri Lanka today remains an undivided country thanks to the military support it received from Pakistan.48

Such closeness of ties between its two neighbours has caused some concern –if not anger -- in India. On many occasions, India has tried to warn Sri Lanka on this issue. India’s former National Security Advisor, M.K.Narayanan, once said: “It is high time that Sri Lanka understood that India is the big power in the region and ought to refrain from going to Pakistan and China for weapons, as we are prepared to accommodate them within the framework of our foreign policy.49” Such concerns aside, it needs to be said that it is India’s apathetic response to Sri Lanka’s defence requirements (due to the compulsions of its own coalition politics50) that has pushed Sri Lanka towards Pakistan and China for succour. In fact, former Lt. General Fonseka had once gone on record in an interview to an Indian TV channel that his country had turned to China and Pakistan for military purchases only after New Delhi refused to supply weapons.51

The spirit of cooperation and mutual bonhomie was again reiterated during a meeting between Pakistani Prime Minister Gilani and Sri Lankan President Rajapaksa on the sidelines of the NAM summit in Egypt in 2009. The meeting was the fourth in a year. Both the sides acknowledged the fact that Sri Lanka was not only a major recipient of armed forces training from Pakistan, but was also one of the main buyers of Pakistani defence equipment.52 Pakistan’s role as a major credit supplier to Sri Lanka was also recognized; the latter utilized the facility for buying railway wagons and defence products,53 mainly from China.

Measures to promote bilateral interactions have continued to grab headlines even after the end of the ethnic conflict in May 2009. But a sudden declaration by the then Chief of Defence Staff, General Sarath Fonseka, calling off US$ 200 million arms procurement deal with China,54 as ordered by President Rajapaksa has put a question mark on the continuation of the post-war defence cooperation with China and consequently, with Pakistan. This has to be seen in a post-poll scenario, where the re-election of Rajapaksa as the President has a major role to play. His ability to balance the activities of India, China and Pakistan has been one of the major factors in his re-election, as opposed to the ‘pro-China, anti-India’ stance taken by his powerful rival, General Fonseka55 and his alliance. Despite several clandestine meetings and visits to India by General Fonseka, the alliance backing him, which also comprised ultra-Marxist JVP, remained more inclined towards China than India. Ranil Wickremasinghe-led opposition United National Party’s linkages with China are an open secret in Sri Lanka.

It is common knowledge that China is one of the biggest arms suppliers to Sri Lanka and is currently engaged in building a big harbour in Sri Lanka at Hambantota. An unnamed Indian security source is of the view that since 2007, China has encouraged Pakistan to sell weapons to Sri Lanka and to train Sri Lankan pilots to fly the Chinese fighter jets.56 Like most of India’s neighbours, Colombo has been astutely cultivating China and Pakistan over the past decades, as a counter balance to India.57 Therefore, low key defense cooperation among Sri Lanka, Pakistan and China is likely to continue with the twin motive of safeguarding their own economic interests and keeping India’s so-called “hegemonic designs” in check.

Post-war Sri Lanka-Pakistan ties – an Assessment

There is a need to have a fresh look at Sri Lanka-Pakistan ties in the new scenario, post- Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict and the re-election of Rajapaksa. While the country will remember with gratitude the arms assistance it received from Pakistan and China in its hour of need, the return of peace to the island has radically shifted the focus of its needs and requirements. It no longer has any urgent need in the defence area and Sri Lanka knew how well to make its peace time choices.

In a three part interview with “The Hindu” Editor-in-chief, Rajapaksa explained Sri Lanka’s relationship with these three powers in the following words: “India was very helpful, first by understanding what was happening. We had a list and we knew what was possible and what was not. We bought the weapons from China. It was a commercial deal. China helps us and when somebody helps you, you appreciate it, don’t you? But we paid them on international terms. We were very clear about this. That is also why I stood by Pakistan. When they were isolated, I got up and defended them. Then I canvassed for India during the process of choosing the Secretary General for the Commonwealth. I always treat India as a friend. A little more than that – a relation, I would say.”58

Rajapaksa made it very clear that Sri Lanka will continue to maintain its friendship with China and Pakistan and, although its relation with India is far more than a mere bond of friendship, he would like to deal with every country on the basis of Sri Lanka’s national interests. Nevertheless, the question arises as to whether a ‘sustainable relationship’ with India can be maintained on this basis alone, given the geo-political proximity and extensive socio-cultural links between the people of the two countries. While investigating Sri Lanka’s relationship with Pakistan and China, it can be said that, as of now, only strong economic ties can bind them together, particularly after the defence aid slid down following the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

While China with its growing maritime capability and large economic interests in the region may be able to maintain its influence, Pakistan’s ability to stand on its own in Sri Lanka is doubtful. In this context, India’s fear regarding Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) infiltrating its southern regions through Sri Lanka is not unfounded.59 However, Prof. Hassan Askari Rizvi, an independent Pakistani political and defence analyst dismisses such fears as exaggerated.60 Prof. Rizvi underlines some areas for future cooperation between Sri Lanka and Pakistan, which include telecommunication, trade and travel interaction and above all, joint measures to combat terrorism in South Asia. Besides, Sri Lanka looks at Pakistan as one of the two counterweights to India. For China, Sri Lanka’s the then foreign secretary Rohitha Bogollagama made it clear during an interview with an Indian news channel that “there can be no defence relationship with China because I see India as our immediate neighbour and a close friend. That also is a unique relationship. India has been very supportive of our efforts for seeking sustainable peace in Sri Lanka. We are quite pleased with the current defence make up of Sri Lanka.”61

India is alive to the possibilities of China and Pakistan doing more business with Sri Lanka, but India’s concerns are not just about economic relations. India is more concerned about the strategic relationship these countries are trying to have with Sri Lanka. Pakistan may be Sri Lanka’s ‘friend in need and friend in deed’62 but Sri Lanka is fully aware of the limitations of this relationship. In 2008, Pakistan failed to get a positive response from Sri Lanka when it offered a defence pact to boost military cooperation between the two countries.63 Likewise, Pakistani government officials are always critical of unfair and inadequate media coverage their country is getting in Sri Lanka as compared to India.64

Pakistan may be Sri Lanka’s ‘true friend’,65 but the island will always look towards India for support and cooperation. On being asked what Sri Lanka wants India to do in a post-war scenario, Prof Rajiva Wijesinha, former Secretary General of the now defunct Secretariat for Conducting Peace Process (SCOPP) and Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Human Rights and Disaster Management, said that Sri Lanka wants India’s support to inform international community about the real intent of Sri Lanka, which is now concentrated on peace and development after the end of the civil war (Wijesinha, Rajiva 2009). Pakistan does not have the international clout needed to convince world community about the genuineness of Sri Lanka’s model of development, as that county itself is mired in various controversies related to human rights violation and terrorism.

However, Sri Lanka is not expected to ignore China and Pakistan, and this reality even India accepts. India also recognizes that as a major world power China, up to a point is bound to have a role and influence in the region. Therefore, there is a need to give enough space to each other for carrying out their respective activities. India also is aware that while its ties with Sri Lanka will continue to be influenced by the ‘Tamil Issue’ and the ‘Tamil Nadu factor’, Sri Lanka-Pakistan/China ties are not subject to any such factor. Nevertheless, there is no justification for any apprehensions regarding Sri Lanka’s growing relationship with other countries, especially, with Pakistan. India should closely monitor the developments and do whatever is necessary to strengthen its own relationship with Sri Lanka. There is, however, no room for complacency in a fast-changing environment of the 21st century. India needs to be able to address Sri Lanka’s core concerns while ensuring its own.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- For more information, see the Sri Lanka High Commission in Pakistan website, (http://slhcpak.org/news/25-11-2007_SL_Pak.html).

- Subramanian, Nirupama. 2009. We won't allow isolation of Pakistan cricket. The Hindu: International (Chennai), March 5.

- The term 'multi-faceted' has been used in Sri Lanka and Pakistani media to describe the multi-level interaction between the two countries in various field.

- Pakistan Government, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2006. Joint Statement. Visit to Pakistan of His Excellency Mahinda Rajapaksa, President of Sri Lanka. Press Release No. 131/2006. April 1. For More Information, see Pakistan Foreign Ministry website, (http://www.mofa.gov.pk/Press_Releases/April/PR_131_06.html)

- Izzadeen, Ameen. 2006. The Love Triangle of Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan. Khaleej Times Online (UAE), April 5. www.khaleejtimes.com

- The News (Karachi). 2004. Pak Initiative Based on Sincerity: PM. November 22.

- Ibid.

- Akhlaque, Qudsia. 2005. Sri Lanka President Arrives: Four Accords to be signed. Dawn (Karachi), February 5.

- Ibid.

- Dawn (Karachi). 2004. Pakistan and Lanka Pledge Partnership for Peace. November 23.

- Khalid, Hanif. 2005. Pakistan, Sri Lanka sign Aviation Agreement. The News (Karachi). March 12.

- Pakistan Government, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2006. Joint Statement. Visit to Pakistan of His Excellency Mahinda Rajapaksa, President of Sri Lanka. Press Release No. 131/2006. April For More Information, see Pakistan Foreign Ministry website, (http://www.mofa.gov.pk/Press_Releases/April/PR_131_06.html).

- Masood, Alaudin. 2005. Pakistan - Sri Lanka: Strengthening Trade Links. The News (Karachi), April 11.

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 2007. Annual Report.

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 2008. Annual Report.

- Ghausi, Sabihuddin. 2007. An Emerging Trade Conduit. Dawn (Karachi), August 27.

- Baabar, Mariana. 2008. Pakistan, Sri Lanka Vow to Combat Terrorism Jointly. The News (Karachi), February 1.

- Ibid.

- Syed, Baqir Sajjad. 2008. Sri Lanka, Pakistan to expand FTA scope. Dawn (Karachi), February 1.

- Ghausi, Sabihuddin. 2007. An Emerging Trade Conduit. Dawn (Karachi), August 27.

- Ramachandran, Sudha. 2010. Diminishing Influence. Geopolitics, New Delhi.

- Ghausi, Sabihuddin. 2007. An Emerging Trade Conduit. Dawn (Karachi), August 27.

- Warushamana, Gamini. 2009. Sri Lanka - Pakistan trade: Minor hiccups, major hindrance. Sunday Observer, November 8. For more information, see (http://www.bilaterals.org/negotiations/Srilanka) accessed on March 2010.

- Ghausi, Sabihuddin. 2007. An Emerging Trade Conduit. Dawn (Karachi), August 27.

- Daily Mirror. 2009. Sri Lanka, President agree to boost multi-faceted bilateral ties. September 1.

- Yatawara, Ravindra A. 2007. Exploiting Sri Lanka's Free Trade Agreement with India and Pakistan: An Exporter's Perspective. South Asia Economic Journal 8:2. 219-247

- Ibid.

- News Line. 2009. Pakistan to share Commercial Intelligence with Sri Lanka. August 4. Also see, (www.priu.gov.lk/news_update/Current_Affairs)

- The News. 2006. Pakistan, Sri Lanka one on Fighting Terrorism. April 1.

- Baabar, Mariana. 2008. Pakistan, Sri Lanka Vow to Combat Terrorism Jointly. The News, February 1.

- Ibid.

- Dawn. 2004. Pakistan and Lanka Pledge Partnership for Peace. November 23.

- Thaindian News. 2008. Sri Lanka's SOS to Pakistan for urgent arms supplies. April 2.

- Sri Lanka still claim that they have not received any Al Khalid MBT from Pakistan

- Press Trust of India. Business Standard. 2009. Pakistan played major role in LTTE defeat. May 28.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The News. 2006. Sri Lanka asking Pakistan for swift Military Assistance: Jane's. June 9.

- Ramachandran, Sudha. 2006. Had Enough? Tigers turn to Pakistan. Asia Times, August 16.

- Mir, Amir. 2009. Pakistan's crucial role in the death of Tamil Tigers. The News International, May 20. Also see, (http://thenews.com.pk) accessed February 25, 2010.

- Baabar, Mariana. 2008. Pakistan, Sri Lanka vows to combat terrorism jointly. The News, February 1.

- Tehelka. 2006. ISI uses Sri Lanka to spread violence in India- Jaffna District MP MK Shivajilingam of the Tamil National Alliance: An Interview with PC Vinoj Kumar. September 30.

- Kapila, Subhash. 2007. Sri Lanka looks to Pakistan for Military Hardware. PlainSpeak, February 3. For more information, see (http://www.boloji.com).

- The Nation. 2006. Pakistan, Sri Lanka vows to fight terror. April 2.

- Online Encyclopedia, Wikipedia. 2009. Pakistan Military Academy, Foreign Alumni.

- TamilNet. 2009. Pakistan's Navy Academy annually trains 70 SLN personnel. September 10.

- Sri Lanka Government. Sri Lanka Navy. 2009. Commanding officer of Pakistani Navy ship 'Zulfiquar' calls on Commander of the Navy. September 5. Also see, (http://www.navy.lk).

- Izadeen, Ameen. 2006. The Love Triangle of Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan. Khaleej Times Online, April 5. (http://www.khaleejtimes.com)

- India's National Security Advisor Mr. M K Narayanan in an interview with the media persons in Chennai after meeting Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M Karunanidhi, May 31, 2007.

- Kapila, Subhash. 2007. Sri Lanka looks to Pakistan for Military Hardware. PlainSpeak, February 3.

- Pakistan Defence Forum. 2009. Pak. Arms, Officers helped Sri Lanka rout LTTE: Report. July 6.

- Daily Mirror. 2009. Sri Lanka President agree to boost multi-faceted bilateral ties. September 1.

- Ibid.

- Reuters. 2009. Sri Lanka cancels $200m arms deal with China, Pak. July 16.

- Ananth, Venkat. 2009. The Fonseka factor. Pragati, December 14.

- Times Online. 2009. China spends billions in Sri Lanka to build port. May 1. (http://www.timesonline.co.uk)

- Pant, Harsh V. 2009. Shape of Sri Lanka's Future. The Japan Times Online, May 1.

- Ram, N. 2009. Rajapaksa says Indo-Lanka relations stronger then a mere friendship. The Hindu, July 8.

- Thaindian News. 2009. ISI could infiltrate through Sri Lanka: Chidambaram. February 25.

- Dr. Hassan Askari Rizvi. 2009. Email Interview by the author. December 31.

- Zee News. 2009. No defence ties with China: Sri Lanka. October 29.

- Subraminian, Nirupama. 2009. We won't allow isolation of Pakistan cricket: Colombo. The Hindu May 5.

- The Nation. 2008. Defence deal offered to Lanka. August 2.

- Izzadeen, Ameen. 2006. The Love Triangle of Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan. Khaleej Times Online, April 5. (http://www.khaleejtimes.com)

- Sri Lanka Government. 2009. Pakistan felicitates Sri Lanka on 'great victory over terrorism. May 23. (http://www.defence.lk)

.

=====================================

Published Date : 18th May, 2011

Post new comment